1963, “An Exhuming Job:” Medardo Rosso, Margaret Scolari Barr, and the MoMA Exhibition*†

Francesco Guzzetti Francesco Guzzetti Medardo Rosso, Issue 6, December 2021https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/medardo-rosso/

The article revolves around the rediscovery of Medardo Rosso in the United States in the early 1960s, with a special focus on the scholarship of Margaret Scolari Barr and the exhibition organized by Peter Selz at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1963. Scolari Barr was thoroughly committed to the reappraisal of Rosso’s art as a pioneering model of modernism, thus positioning the Italian sculptor in the lineage of Western modern and contemporary art. By analyzing her contributions on Rosso—primarily the monograph published in 1963—I aim to demonstrate that Scolari Barr was a scholar and a critic in her own right, who asserted her critical voice through the study on the artist. The book was supported by the organization of a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which is reconstructed in the appendix of the article, with as much information as I have been able to find thus far. The relevance of the exhibition lies in the possibility to investigate the early fortune of Rosso in the American art market and evaluate how the appreciation of his art fit within the taste of major collectors and museums overseas. The double initiative of Scolari Barr’s book and the MoMA exhibition marks a watershed moment in informing the international reception of Medardo Rosso and defining his legacy.

The exhibition Medardo Rosso (1858-1928), organized by Peter Selz at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (October 2 – November 23, 1963), and the concurrent publication of the monograph Medardo Rosso by Margaret Scolari Barr, marked a turning point in the international reception of the Italian sculptor. Not only did the exhibition and the book contribute significantly in reassessing the position of Rosso as a protagonist of the art of his own time, but they also fostered the appreciation of his radical practice as a model and reference for contemporary art. The book authored by Scolari Barr has been extensively mentioned, quoted and discussed, but it has never been acknowledged as the means by which the author articulated and affirmed her own critical voice. On the other hand, the exhibition has never been properly analyzed as a significant initiative which attested to the early circulation of Rosso’s sculptures on the art market in the United States. This article is followed by the reconstruction of the exhibition, which is meant to be as informative as possible with regards to the provenance, exhibition and publication histories of the works on view.

The exhibition and the book are intertwined; the first was indeed intended to promote the latter, which was published by the Museum of Modern Art in association with Doubleday Press. Important decisions about loans were discussed between Selz and Scolari Barr. Her expertise on Rosso was developed through years-long research and several trips all over Europe, and Italy especially, by means of which she honed her knowledge of the artist’s practice to an extent that she acted as an advisor in the making the exhibition. On the other hand, a few aspects of Selz’s choices for the exhibition diverge from the view of Rosso’s oeuvre elaborated by Scolari Barr. Commonalities and discrepancies should be carefully examined in order to understand the significance of the respective presentations of the Italian sculptor.

The mission of the project was captured by Peter Selz in a letter to his colleague Palma Bucarelli, the director of Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, in Rome. In light of the difficulties in obtaining a few crucial loans, Selz felt like he needed to emphasize the importance of the initiative in the following terms: “We have purposely scheduled the Medardo Rosso exhibition right after our show of Rodin in order to make clear the difference in thought and achievement of these two artists who have, unfortunately, been coupled by legend in the mind of many critics. It is very important to show the great differences between them even though they are both classified as “impressionist sculptors.” Outside Italy the name of Rosso is still little known. We would like to obtain for him the recognition and world acclaim that his work deserves. […] As you know, Mrs. Margaret Scolari Barr has written a comprehensive and penetrating monograph on Medardo Rosso which will be published by us in conjunction with the exhibition. I am enclosing the introduction to this book which will indicate its importance to you. The Rosso exhibition and monograph constitute a new departure. I think it is fair to say that, with the exception of Canova, Italian sculpture between Bernini and Boccioni is virtually ignored abroad. Rosso is an exception but he is still very little known. We believe this neglect is deplorable. To rectify it we ask your help and the help of your museum. To impress the sophisticated New York public (and justify our own enthusiasm!) we must represent Medardo Rosso at his best. In short, we should have all his six or seven capital works. We need them urgently. I do not, my dear Dottoressa, wish to seem importunate. We understand your reluctance. Yet we think that this may be an occasion when some risk is justifiable.”1

One could argue that the letter was just meant to convince Bucarelli to lend the pieces which had been requested. Nonetheless, Selz provided a rather accurate report on the state of the art of the reception of Medardo Rosso in the United States by the time of the exhibition which he was organizing. The scant knowledge of Rosso in the United States should first be considered by briefly hinting at the postwar reception of the Italian sculptor overseas.

- Rosso in the United States, 1945 to 1963

The first occurrence of the name of Medardo Rosso in the United States after World War II is most likely the translation of one of his major writings in an anthology titled Artists on Art: From the XIV to the XX Century, from 1945.2Consisting of a selections of texts, spanning six centuries from Cennino Cennini in the Middle Ages to José Clemente Orozco, in which artists articulated and expressed their vision of art and art making, it would gain increasing recognition as a primary source of information for scholars.3The anthology was compiled and edited by Robert Goldwater and Marco Treves. Both graduate students at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, Goldwater and Treves acknowledged the contribution of their professors in the foreword of the book, with special mention of Erwin Panofsky and Walter Friedlaender.4 While Goldwater would become a renowned art historian and museum director, Treves is a rather obscure figure. He was an Italian Jew who fled from his country in 1938 and emigrated to the United States.5His education at the Institute of Fine Arts is attested by the publication of an article in the journal of the Institute’s students in 1941.6As the editors claimed in the foreword, many of the artist’s statements in the anthology were published in English for the first time, with Treves translating the Spanish and Italian texts. The editors endeavored to provide a comprehensive selection of Western artists by merging history and geography. The resulting structure of the book consisted in a chronological sequence of chapters, in which the artists were grouped by their country of origin. The presence of Italian artists dramatically decreases starting from the sections devoted to the 19thcentury. Among the few mentioned names, Adriano Cecioni, Medardo Rosso, and Giovanni Segantini represent the contribution of Italy to the art of the late 19th century. In the introductory essay, Goldwater emphasized the revelatory nature of the artists’ own words when applied to their practice.7Complying with the intention to focus on such sources, it was that the statement that Rosso published in Edmond Claris’s famous survey on Impressionism in sculpture in 1902 would be translated from French.8It was the first English translation of this writing. In the short introduction to the text, the Italian sculptor was primarily associated with the category of Impressionism: “Medardo Rosso is the most typical representative of “impressionism” in sculpture. For the interplay of volume and contours he substituted an interplay of light and shadow.”9

The inclusion of Rosso’s text in Artists on Art is early, yet significant, evidence of the modernity of his vision. In this respect, one might wonder whether the decision was also inspired by the artist Louise Bourgeois, to whom Goldwater was married, who was acknowledged in the book “for criticism from the point of view of the contemporary artist.”10Despite this intriguing assumption, it’s not so hard to guess how the editors came to know of Rosso. Among the people to whom they expressed their gratitude in the foreword, Alfred H. Barr was also mentioned. It was probably Barr who brought the Italian sculptor to the attention of Goldwater and Treves. A few years later, Barr and James Thrall Soby would acknowledge Rosso as “revolutionary precursor of Rodin at his boldest” and “a sculptor of international importance and influence” in the catalogue of the exhibition of Italian modern art, which they organized at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1949.11 The relevance assigned to Rosso by Barr and Soby is significant, yet problematic. Despite the insistence in asserting the primacy of his art on an international scale, the sculptor was hailed as a pioneering figure only with regards to the development of modern art in Italy. On a broader level, the historiography of modern Western sculpture in the United States still positioned Rosso as a peripheral figure. Following the assessment of the artist in the anthology by Goldwater and Treves, the prevailing narrative around the sculptor still revolved around his association with French Impressionism.

In 1952, a major publication on modern sculpture in Europe and the United States was released, not so far from the museum where Italian art had been celebrated a few years earlier. The book was published by the Museum of Modern Art, and authored by Andrew C. Ritchie, who was the director of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the museum. Building upon what was considered as the unquestionable preeminence of Auguste Rodin as the pioneer of modern sculpture, Ritchie treated Rosso as the antagonist of the French master, his “Italian counterpart”, whose nature was that of “an impressionist painter in wax” with a weaker sense of mass and space.12 Ritchie placed Rosso among the artists gravitating in the orbit of such a towering figure as Rodin, yet recognized his role as the initiator of Italian modern sculpture.13 Two works by Rosso, a plaster version of Malato all’ospedale [Sick Man at the Hospital] and a wax of La conversazione [Conversation in a Garden], both from the collection of the heirs in Barzio, were illustrated among the plates of the book.14 The study anticipated a major exhibition of sculpture organized by Ritchie, which travelled among the museums in Philadelphia, Chicago and New York.15 Taking its cues from the publication, the initiative reasserted the exclusive centrality of Rodin’s work as the origin of modernity in sculpture. No artworks by Rosso were exhibited, while his name was mentioned only once in the accompanying catalogue, in the short biography of the Italian sculptor Giacomo Manzù.16

It took a little longer before Rosso was (re)discovered as an international protagonist in the history of modern sculpture. In 1955, the substantial analysis of modern sculpture, authored by the German-Swiss art historian Carola Giedion-Welcker, was released in Germany, United Kingdom and the United States.17 The book was the larger and deeply revised edition of the study that Giedion-Welcker had already published in 1937.18 Based in Europe and engaged in championing modernist sculpture for a long time, the author was up-to-date on many artists who were lesser known in the United States at that time, including Rosso. In Giedion-Welcker’s analysis, Rosso countered Rodin inasmuch as the practice of the former was more lyrical, delicate and attentive to the surface of the sculpture, while the latter was more concerned in the dramatic and dynamic effects of huge masses. The art historian contended that the great artistic achievement of Rosso “was the use of light to dematerialize volume,”19 and recognized his influential role by illustrating several of his most radical sculptures, often compared to works by younger artists, who might have been inspired by him. In this respect, it’s important to notice that Giedion-Welcker analyzed and included the heads of Yvette Guilbert and Madame X among the plates of the book, illustrated the groups of La Conversazioneand Impression de boulevard. Paris la nuit [Boulevard impression. Paris at night], and ultimately compared Rosso’s Enfant malade [Sick Child] to Brancusi’s Supplice and Lehmbruck’s Female bust, and the grotesque profile, full of edges, of La portinaia [Concierge] to Boccioni’s Antigrazioso [Antigraceful].20

Giedion-Welcker’s scholarship definitely facilitated the circulation and reappraisal of the work of Rosso among American critics and collectors. A few years after the publication of her book, the dealer Louis Pollack, who ran the Peridot Gallery in New York, took increasing interest in Medardo Rosso. Margaret Scolari Barr would recall the circumstance of the dealer’s encounter with Rosso’s art, and assign a seminal role to that event. A few sheets of notes are currently kept in the MoMA archives, in which Scolari Barr detailed the story.21 These notes were most likely addressed to William C. Seitz, curator of the Department of Painting and Sculpture Exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, to provide him with a draft to use to introduce the lecture that Scolari Barr gave on Rosso at the museum on November 5, 1963.22 Scolari Barr explained that “after the second war Lou Pollack of Peridot was tremendously interested in the very complete series of Rosso sculptures in the Galleria d’arte moderna in Rome. He asked around and by 1959 he had some Rossos for sale.”23

The exhibition arranged by Pollack consisted of a small, yet exhaustive, selection of sculptures and drawings by Rosso. Held at Peridot Gallery between 1959 and 1960, it was the first retrospective of the Italian sculptor in the United States, and a watershed event in the acknowledgement of the artist.24 Ten years later, on the occasion of the obituary for Pollack’s untimely death, Hilton Kramer would still remember the exhibition as a groundbreaking revelation.25 Consisting of twelve sculptures and two drawings, the exhibition aroused interest in the artistic milieu at that time.26 Based on the reviews, the wish to assert the radical modernity of Rosso’s art and his role as a “teacher for the artists of the new generation who recognized his valor and power,” as formulated in the introduction of the catalogue by Giorgio Nicodemi—former director of the museums of the city of Milan, editor of the Italian magazine L’arte, and a partner of Pollack in the organization of the exhibition—was accomplished. Dore Ashton authored the more insightful report on Rosso’s art, which she defined as “prophetic.” For the first time, the association with French impressionism felt reductive vis-à-vis the complexity of the forms modeled by the artist. Ashton described the artist’s sense for the transparency of light and atmosphere, by means of which he expressed his “new vision of the universe” as a whole, which objects participated in, and sought the pure form laying underneath the transient and ever-changing impressions of reality.27

In the most extensive review of the exhibition, which appeared in Arts magazine with several full-page illustrations of sculptures, Hilton Kramer articulated what Ashton hinted with regard to the internal dialectic of Rosso’s sculpture. The artist could finally compare to Rodin at the same level, and look even more modern than the French: “Rosso’s art looks to the future. Compared with Rosso, it is Rodin who looks like the latter-day master of the Renaissance.”28 Dismissing the label of Impressionism, Kramer contended that the raw surfaces through which the artist rendered the human figures resonated with modern Expressionism, and Giacometti’s figures, while the purity of his forms, verging on the dematerialization in light and space, anticipated Brancusi’s quest for essentiality and the unitary worldview of Futurism. The apparently opposing poles of modernity reconcile in the art of Rosso, whose “realism was thus motivated by a quest of purity, and the purist aspect of his work was abetted by a desire to render the truth.”29 Other reviewers, such as Bennett Schiff, agreed with Kramer’s interpretation.30 Emily Genauer went even further, and argued that Rosso’s work would resonate with the vision of young artists more than Rodin’s: “Today’s sculptors—painters, too—are more interested in light, surface and space. They are absorbed by shapes in metamorphosis, by images that are not fixed but forever in process of becoming. They cannot, however, accept the rhetoric, the heroics, even, of much of Rodin’s work. In the few Rosso pieces they’ve run into […] they have spotted qualities similar to those they are seeking.”31 The appraisal of the legacy of Rosso by American critics around the time of the exhibition at Peridot Gallery is partially attested by the occurrence of his name in the catalogue of the fundamental exhibition New Images of Man, organized at the Museum of Modern Art in Fall 1959.32 Describing the war monument designed by Kenneth Armitage for the Germany city of Krefeld, Peter Selz, the curator of the exhibition, paired Rodin and Rosso as sources of inspiration for the rough treatment of the surface of the sculpture.33

The perception of Rosso in the United States radically changed throughout the 1960s. From the periphery of the art world centered in France and dominated by Rodin, the Italian sculptor was slowly positioned right at the center and acknowledged as a modern master standing at the same level as his French colleague and prefiguring the development of modern and contemporary sculpture. In this respect, the intuition expressed by Barr and Soby in the catalogue of the 1949 exhibition was articulated in 1961, on the occasion of the exhibition on Futurism, organized at the Museum of Modern Art.34 In the accompanying catalogue, Joshua C. Taylor included a full-page plate of Rosso’s Yvette Guilbert35 Taking cues from the homage to Rosso paid by Umberto Boccioni in his Manifesto of Futurist sculpture, Taylor contended that Rosso held a central position as a pioneering figure of Italian and international avant-garde.36 Pollack’s efforts to arouse interest in Rosso led to the increasing number of his sculptures entering major American public and private collections starting from the exhibition at Peridot Gallery.37 In this respect, the scholarship of Margaret Scolari Barr was fundamental in reassessing the relevance of the artist, which was definitely sanctioned by the exhibition organized at the Museum of Modern Art in 1963.

- A scholar in her own right: Margaret Scolari Barr on Medardo Rosso

In conjunction with the exhibition at the Peridot Gallery, an insightful scholarly examination of the art of Medardo Rosso was published in Art News.38 It is a detailed profile of the artist’s life and body of work, rather than a commentary or a review of the exhibition. The author was Margaret Scolari Barr. The art historian felt the need to provide the American audience with a proper contextualization of the artist whose work looked so shockingly fresh and modern to anyone visiting the exhibition. The accuracy of the reconstruction revealed the depth of knowledge and the extent of the research by means of which Scolari Barr could retrieve so much information about the Italian sculptor.

The activity of Margaret Scolari Barr is extremely relevant and multifaceted. A comprehensive reconstruction of her figure would extend far beyond the scope of this article. Since the files of her archive were processed and opened to access at the MoMA archives, a few reports on her life and work have been published.39 Born in Rome in 1901 from an Irish mother and an Italian father, Margaret Scolari was a natural polyglot, thanks to her multilingual family background. She studied linguistics in Italy, then moved to the United States to teach Italian at Vassar college, where she started her education in art history. Her fluency in French, Italian, Spanish and German enabled her to build up a network of relationships in Europe and facilitate the acquaintance with the sources and protagonists of modernism of her husband, Alfred H. Barr, whom she married in 1930 (Fig. 1).40 Scolari often collaborated with Barr on exhibitions and publications, and frequently travelled throughout Europe with him.41 The couple frequently stopped in Italy, where Scolari had important acquaintances in the art world, including the Futurist painter Giacomo Balla, who was a close friend of her father, the Ghiringhelli brothers, who ran Galleria del Milione in Milan, and Bernard Berenson.42

Margaret Scolari and Alfred Barr at the Venice Biennale in 1948.

According to Scolari Barr’s own notes, the encounter with Medardo Rosso was facilitated by her husband, who had been fascinated by his sculpture since the early travels in Europe in the late 1920s.43 A more consistent interest in his work more likely dated to the trips to Italy in the postwar years, when Scolari, Barr and Soby were preparing the exhibition on Italian modern art to be held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1949.44 Several years later, Scolari briefly recalled the circumstances of the development of her approach to Rosso. In 1977, Francesco (Franz) Larese, who ran the publishing house Erker Presse in St. Gallen, Switzerland, specialized in prints and limited editions, reached out to Scolari through the Italian artist Piero Dorazio, asking whether she were interested in working on a new, updated edition of her 1963 book on Rosso.45 After detailing her response, the art historian added a post-scriptum, in which she recounted as follows: “Before getting married, I had done tremendous studies in art history. Then, as the wife of Alfred Barr, I learned more than you could learn at university. When Alfred announced at home that a book on Medardo should be written, I immediately realized that such a work should be done by me.”46 The story is confirmed by a letter, held at Archivio Rosso, that Alfred Barr sent to Francesco, the son of the sculptor, in 1949. Taking its cue from a report by James Thrall Soby of a visit to Barzio, the town in the mountains over Lecco where Francesco had his vacation house and created a museum with many of his father’s sculptures, Barr regretted that the acquisition committee of the Museum of Modern Art couldn’t buy a sculpture by Rosso, due to the little knowledge of the artist in New York at that time, but expressed his enthusiasm about him as “the most original artist of his country during that period.”47 As part of the intense schedule of international trips taken every year with her husband, Scolari must have visited the major retrospective of Rosso organized at the Venice Biennale in 1950.48 The exposure to such a comprehensive selection of sculptures and drawings most likely felt like a confirmation of Barr and Soby’s interpretation of Italian modern sculpture as a lineage stemming from Rosso’s radical practice.49

Scolari’s research on Rosso, the exhibition at Peridot Gallery and the concurrent acquisition of two sculptures, Portinaia and Bookmaker, by the Museum of Modern Art in 1959, constituted a concerted effort to foster the recognition of the artist in the United States.50 According to Scolari Barr’s memories, after securing two sculptures to the museum collection, Alfred Barr “wanted someone to write something on Medardo.”51 In the notes left to William C. Seitz to help him prepare the introduction to the lecture that she gave at the Museum of Modern Art in November 1963, the art historian understated the importance of her scholarly contribution, maintaining that Barr asked her to study Rosso primarily for her linguistic skills, as the majority of the bibliography on the artist was in Italian.52 In this respect, Giorgio Nicodemi, who was also involved in the organization of the exhibition at Peridot Gallery, assisted Scolari Barr in developing her expertise on Rosso, as attested by the correspondence between the two of them in those years. Scolari sent him the catalogue of Peridot Gallery along with her article in Art News in early 1960. In the accompanying letter, the author thanked him for providing essays and sources, and complained about the editorial restrictions that forced her to trim her essay. The art historian therefore expressed the desire to publish a more comprehensive survey on the Italian sculptor elsewhere, and asked for Nicodemi’s support in reaching out to the family of the artist and whoever was in contact with him.53

In the article in Art News, Scolari Barr emphasized especially two figures who intersected Rosso’s life and art: Rodin and the Dutch collector and art patron Margaretha (Etha) Fles. The art historian engaged in a thorough investigation of their relationship with Rosso, which she would develop further in the essays published in the following years. The depth and breadth of Scolari Barr’s knowledge in this respect reveals her commitment as a scholar. The troubled relationship with Rodin and the issue whether the Italian inspired the composition of his Balzac marked the critical interpretation of Parisian years of Rosso.54 Getting rid of the misinterpretations and the biases which had accumulated in the scholarship until then, Scolari Barr argued that Rosso’s sculptures might have possibly inspired Rodin’s solution, acknowledging at the same time the major differences between the works of the two sculptors. Scolari Barr’s effort was immediately acknowledged, to the extent that a few years later, Albert Elsen, a leading authority on Rodin, decided to just briefly hint at the connection with Rosso in the monograph on the French sculptor accompanying the retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, which preceded the Rosso exhibition. Instead of providing his own interpretation, Elsen left a broader discussion of the subject for the monograph by Scolari Barr, which would appear shortly afterwards.55 With regards to Etha Fles, the art historian reserved the concluding paragraph of her article in Art News entirely to her, recognizing her pivotal role in championing inexhaustibly the art of Rosso.56

The exploration of these issues developed in conjunction with the extension of the scope of Scolari Barr’s research on Medardo Rosso. After the publication of the article, there began an intense period of research and travels. Scolari Barr spent long time in Italy, trying to gather as much information as possible, meet friends and acquaintances of the artist, get the sculptures in public and private collections photographed, and visit as frequently as possible the heirs of Rosso in their property in Barzio, where documents and works were kept at that time. Scolari Barr first visited Barzio on August 4, 1960, as attested by the correspondence with Clotilde Rosso, the widow of Francesco, Medardo’s son, and her daughter Danila, as well as by a letter sent from the United States, in which Scolari thanked Clotilde Rosso for the exquisite hospitality and expressed her desire to study the archive.57 Upon reception of the letter in which the art historian asked for his help in reaching out to the family, Giorgio Nicodemi facilitated the visit and introduced Scolari to Rosso’s heirs in the summer of 1960.58 By that time, the project of a book, intended to be published by the Museum of Modern Art, had already been established.59 Scolari’s effort to get the works properly photographed was primarily meant to provide the publication of the book with as many accurate illustrations as possible. When Gino Ghiringhelli of Galleria Il Milione gave her most of the photos which were used by Mino Borghi for the monograph published in 1950, Scolari found some of them outdated, and tried to commission a new photographic campaign.60 The Rossos hosted Margaret Scolari in Barzio at least in the summer of 1960 and 1961. They showed her the artist’s sculptures and drawings, allowing her to take photographs which would be partly illustrated in the book released in 1963.61 Apparently, despite the hospitality, she couldn’t study some of the papers, probably because they had already been used and mentioned in the 1950 book by Borghi.62

Scolari became interested in the figure of Etha Fles since the beginning of her research on Rosso, while she was determining the chronology of the artist’s body of work. By the summer of 1961, Scolari had already gathered enough material about the Dutch woman, and was working on an article which would be published in the Netherlands.63Titled “Medardo Rosso and His Dutch

ss Etha Fles,” the essay appeared in Netherlands Yearbook for the History of Art at the end of 1962.64 The story of Scolari Barr’s interest in Etha Fles was recounted directly by her in a letter to Nicodemi, in which she provided a short biography and retraced the origins of her studies on Rosso: “At the time when I wrote the article for Art News, I had already realized that this Dutch lady was standing in the background. A Dutch woman, who works at Kröller Müller Museum, read the article and sent me the address of the adopted daughter of Fles. I reached out to her and began to understand countless aspects which weren’t mentioned in Italian monographs. Time passed and my husband and I went to Berlin in 1960 for a Congress on Cultural Freedom [sic].65 I met there Abraham Maria [sic] Hammacher, the director of Kröller Müller Museum, and asked him whether he had memories of this Etha Fles. And he said: “of course I do,” and added that she was a beloved intellectual, much admired in the Netherlands. Therefore he commissioned the article on Fles and told me that he would submit it to the Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art. I thought about writing a short piece of approximately 3 pages. Nevertheless, in 1960 as well, shortly after meeting you in person, I met by chance a strange Dutchman in Venice. I forgot to bring with me in Italy the address of the adopted daughter [of Etha Fles], then I gave a letter to him, to be brought back to the Netherlands. This really strange guy, half a journalist, half an historian, went to visit the adopted daughter and, like a detective, started to search, talk, go to libraries, to find out articles and relatives of Fles. He then sent me in scattered letters, extremely hard to read and inconsistent, mostly all the material I used for the article, which reveals another aspect hitherto unknown in the life of Medardo. In fact, the friendship with Fles was actually a miracle for Medardo, not only for the reasons which are clear in the article, but mostly because she deeply admired him and encouraged him at a time when he was neglected in Paris.”66

In the opening paragraphs of the article, Barr revealed the identities of the figures mentioned in the letter. The adopted daughter of Etha Fles was Agatha Verkroost, while Jacob van der Waals was the name of the journalist who provided Scolari with most of the documents concerning Fles.67 In addition, the art historian applied her linguistic skills to learn Dutch to read the articles and books authored by Fles, and integrated the memories shared by Alexandrine Osterkamp, a longtime friend of the woman.68 The research resulted in an insightful and intense portrait of Etha Fles. Scolari published several archival documents which substantially integrate the knowledge of the role of the Dutch woman in championing Rosso’s art, thus making the essay a major reference for the scholars still today. The figure of Etha Fles impacted on defining aspects in the practice of Rosso, such as his effort to promote his art on an international scale, his problematic settlement within the Parisian art context, and the definition of his revolutionary sculptural style. Reassessing the centrality of Etha Fles in the biography of Rosso, Scolari Barr achieved to assess the centrality of the Italian sculptor himself as a protagonist in the art of the late 19th century and a model for the avant-garde rising in early 20th century. By doing so, she ultimately asserted her own critical voice and expertise in the field. In the contextualization of the role of Fles, the art historian addressed at full extent the crucial issue of the influence of Rosso on Rodin’s Balzac. Taking cues from Fles’s passionate defense of the primacy of Rosso and his Bookmaker over Rodin’s solution for his monument, Scolari Barr gathered and collapsed the interpretations which accumulated throughout the years. In light of this scrupulous survey, she finally elaborated her own vision, which was way more articulate in determining the commonalities between the sculpture of Rodin and works like La conversazione, Malato all’ospedale and Bookmaker by Rosso, as well as the differences which identified their respective practices.69 Scolari thus paved the way to the more nuanced interpretation of this subject in the reconstruction of Rosso’s years in Paris, which is currently accepted by scholars.[70]70

The article reinforced the relationship with Nicodemi, who kept assisting her as much as possible by providing books and sharing sources, thus proving to be an invaluable reference in the development of Scolari’s expertise on Rosso. As such, the Nicodemi’s name was mentioned among the first names in the acknowledgments of the monograph on Medardo Rosso published in 1963.71 Scolari Barr wrote the book over a period spanning more than three years. As recalled by the art historian, the monograph was officially commissioned by Monroe Wheeler, head of the Exhibitions and Publications departments at the Museum of Modern Art, on April 4, 1960.72 The article on Etha Fles was explicitly introduced as the result of the writing of the concluding chapters of the book which would be released shortly afterwards.73 The monograph marked the culmination of the thorough research which Barr undertook to unveil and reconstruct the complex figure of Rosso as precisely as possible, as attested by the long list of people acknowledged in the book.

By the time of the release of the book, the relationship with Italy was getting into a problematic turn. In a letter to Nicodemi, Scolari wished to publish an Italian edition of the article on Fles.74 Nicodemi was able to fulfill her request and included the essay in an issue of the magazine L’Arte, of which he had been editor, in 1963.75 Scolari’s desire stemmed from the resurgence of interest in Medardo Rosso at the turn of the 1960s, which was mostly triggered by her research on the sculptor. In 1961, Luciano Caramel, an art historian who would devote many studies to Rosso and assist the artist’s heirs for a long time, published a survey on the early activity of the sculptor in the magazine Arte Lombarda.76 In the introduction to the article, the scholar recognized the reappraisal of Rosso in the United States—although Scolari Barr’s name was not mentioned—and asserted the importance of the research on the artist’s early years as a contribution and response to such an increasing reconsideration overseas.77 Scolari Barr was in touch with Caramel and acknowledged the importance of his article in the letter to Nicodemi, but claimed at the same time that much information published there had first been retraced by her, thus emphasizing the importance of getting her study on Fles published in Italy.78

Scolari Barr’s book demonstrates her thorough commitment as a scholar at the fullest extent. By gathering and collapsing archival documents, memories, and witnesses by as many friends and acquaintances of Rosso as she could find, Barr realized a substantial contribution in the reappraisal of the Italian sculptor, which would become a reference for the scholarship which developed thereafter. In the book, the author could properly articulate her argument concerning the relationship with Rodin and the possible influence of Rosso’s work on the sculpture of the French artist, by virtue of which she assessed the modernity of the body of work produced by Rosso (Fig. 2).79 Building upon the analysis already included in the article on Fles, she also convincingly demonstrated that Madame Xdates as early as 1896, thus questioning the assertion of the execution in 1913 maintained by Mino Borghi, who had been the leading authority on Rosso until then.80 The depth of her knowledge of the existing bibliography on Rosso, which she scrupulously parsed with regard to the definition of the chronology of the sculptures, was countered by the presentation of unpublished sources, such as the early portrait of Baldassare Surdi and the correspondence documenting the acquaintance between Surdi and the artist.81 The discovery of the painting and the papers was made possible by the Italian writer and intellectual Giuseppe Prezzolini, who befriended Scolari Barr during his tenure as professor emeritus at Columbia University and assisted her by sharing his own memories and documents of his friendship with the sculptor and facilitating her contacts with people in Italy, such as Surdi’s daughter-in-law.82 Prezzolini was one of the several witnesses, ranging from Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti to French critic Christian Zervos, whose voices were integrated by Barr within the archival reconstruction of Rosso’s life and the art-historical appraisal of his body of work, thus adding human intensity to the vivid portrait of the artist delineated in the book.83

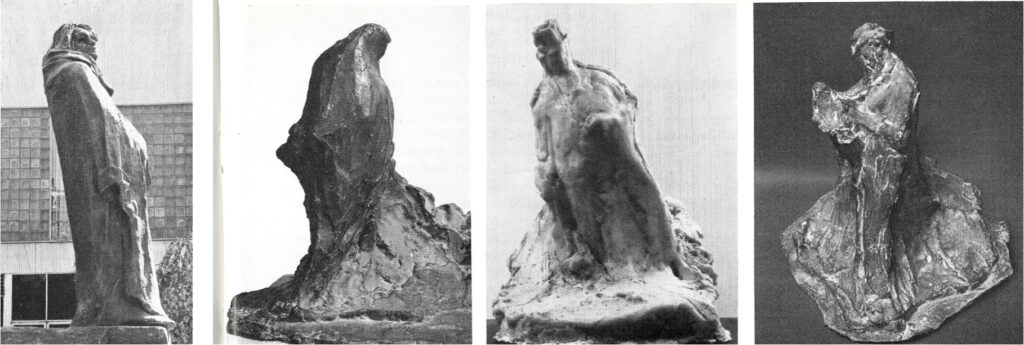

The comparison between Rodin’s “Balzac” (left) and three figures sculpted by Rosso (from left to right: Detail of “La conversazione”, “Bookmaker”, “L’uomo che legge”).

A few major aspects in Rosso’s practice were misunderstood, such as his use of photography. The importance of the artist’s practice of taking multiple photographs of his sculptures was briefly acknowledged only once in the book, while discussing his mature production in Paris: “Like Brancusi, Rosso insisted that his sculpture be reproduced only from photographs taken by himself because he felt that his impressions should be seen in one light and at one angle, just as he had beheld them in their transitory reality.”84 Due to the sporadic access to the artist’s files kept by the family at that time, including the majority of his photographs, and the general lack of recognition of this production, Scolari did not quite have the chance to investigate and acknowledge the significance of photography as a practice whose scope extended further than the promotion of the artist in the press, and embraced the inexhaustible process of revisiting and reconfiguring the sculptures by means of the technical manipulation of the mechanical image.85 Overlooking the artist’s photographs, the art historian couldn’t really examine his activity in the late years, after the realization of Ecce Puer, and focused instead on major exhibitions and his critical reception.86 On the other hand, Scolari Barr recognized the importance of his works on paper, arguing that the freshness and modernity of Rosso’s drawings attest to the extent of his mastery in incorporating the pictorial language of the most advanced tendencies at the time into his practice.87

Several aspects of primary importance were emphasized in the visual and artistic analysis of the sculpture of Rosso, including the artist’s attention to the relationship between the figure and the ambiance and the opening of sculpture to space and light environment (on the edge between the sense of the optical instantaneous impression and the de-materialization), the specific treatment of the surface, the replication—by means of which the same subjects varied in size, composition and surface from one version to the other—and the combination of pictorial and sculptural features. The accurate appraisal of the artist’s visual concern led Scolari Barr to reject the exclusive association with French Impressionism, which had been dominant until then, and reassess instead the primary role of Rosso as a model for the avant-garde artists emerging at the turn of the 20th century. In this respect, the comparison with Brancusi, established by the art historian in the abovementioned paragraph on Rosso’s use of photography as a means of self-presentation, extended further to include the possible influence of the Italian’s work on the Romanian’s vision of sculpture.88 Futurism held a primary position in acknowledging the role of Rosso, and Scolari Barr discussed the importance of the movement in defining his legacy as a modern master, expanding upon what had already been suggested by Taylor in the catalogue of the exhibition on Futurism in 1961.89

In this respect, the book and the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art constitute a substantial and insightful analysis of the practice and legacy of Rosso. As attested by the letter quoted in the opening of this article, Peter Selz, the curator of the exhibition, was well aware of the significance and ambition of the scholarly work undertaken by Scolari Barr. To properly analyze the exhibition, the contribution provided by the expertise of Scolari Barr cannot be neglected.

- “Medardo Rosso at his best:” the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art

Selz had thought about an exhibition on Medardo Rosso for a long time: since Margaret Scolari Barr started to elaborate her monograph. In the letter that accompanied the delivery of the finished manuscript to Selz, the art historian reasserted the importance of the initiative by advocating once again for the necessity of a substantial reappraisal of Rosso.90 It was early January 1963, and Scolari Barr remarked that the sculptures lately exhibited as part of the Hirshhorn collection at the Guggenheim Museum didn’t go unnoticed.91 In light of such appreciations, the art historian wrote: “Maybe I’m prejudiced but I am convinced that Medardo is very much “in the air.” This summer in Salisbury Tristan Tzara informed Alfred that there was one sculptor that had been seriously overlooked—Medardo Rosso; had he heard of him? […] None of these writers know much about Rosso but they keep mentioning him because he’s something of a new discovery. I don’t need to remind you that there are five Rossos in the Hirschhorn Collection. I have written more than originally requested but it is impossible to write a good essay on quicksand. […] Rosso had to be dredged up. No one had done any serious research on him. It was an exhuming job and one that to be done quickly while some of the oldish people who remembered him were still alive.”92

Margaret Scolari Barr acted as an advisor to Peter Selz. She brought to his attention important works, starting from Madame X, whose inclusion was of primary importance.93 The art historian also pointed out a few essential aspects to provide an insightful presentation of the artist’s work. For instance, she encouraged Selz to borrow multiple versions of a same work, to show the sense of variation within the repetition, which was distinctive of Rosso.94 She also advised on potential collectors and lenders to contact, such as Cesare Fasola, the owner of the unique version of Amor materno.95 On the other hand, she expressed doubts about the inclusion of a controversial sculpture as the wax of Impressione d’omnibus, which was exhibited anyway.96 In return for her assistance in many essential aspects of the exhibition, Selz supported Barr’s project to get her book translated into Italian. The curator reached out to institutions both in New York and in Italy to sponsor and partially fund the publication, and a few Italian publishing houses were contacted.97 Unfortunately, the Italian edition was never released.

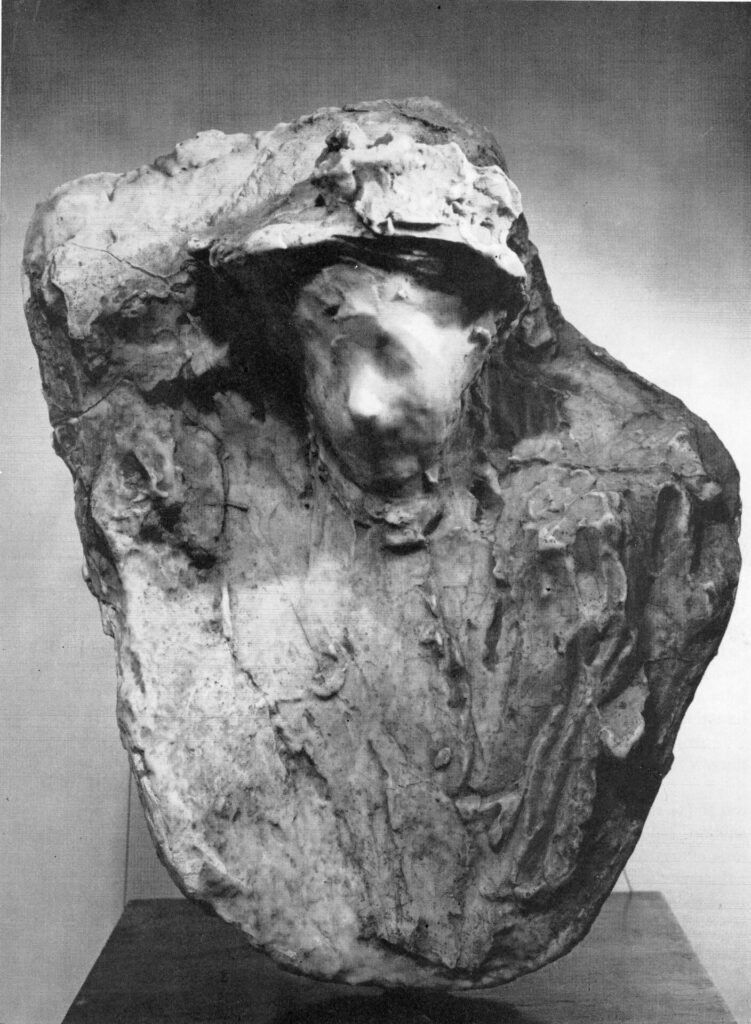

More importantly, Scolari Barr was influential in finalizing the schedule of the exhibition. In fact, the first plan elaborated by Selz entailed that the retrospectives on Rodin and Rosso would take place at the same time, his intention being to provide a comprehensive view of the work of the leading sculptors of their generation side by side.98 Scolari Barr vehemently advised against this decision, as attested by correspondence exchanged in the summer of 1962. By that time, the art historian had already accomplished the essay on Etha Fles and was convinced that the traditional interpretation—emphatically maintained by the Italian scholars—by virtue of which Rodin “stole” ideas from Rosso while making the Balzac monument, should be radically downscaled and rejected, in favor of a more nuanced reconstruction of the relationship between the two sculptors, based on a deeper acknowledgement of their respective similarities and divergences. In a letter to Albert Elsen, who was writing the monograph on Rodin which would accompany the retrospective at MoMA, Scolari Barr insisted that “whether he influenced the Balzac or not, Rosso’s influence lies in the 20th century and I must say I do disapprove of the Museum’s plan of showing these two artists together, even in separate shows, because it nails once more an incidental, perhaps possible influence which has been swelled by Italian scholars, who don’t have a panoramic view, into exaggerated, constantly perpetuated proportions. […] I have already said to dear Peter Selz that I think this juxtaposition, even in separate shows is against the intellectual tradition of the Museum. Because it perpetuates an unscholarly fact. And anyway whether Rosso by his work or his conversation influenced the Balzac I see no later influence of his upon Rodin.”99 Elsen agreed with Scolari Barr. Ultimately, Selz followed her advice, too. In addition to the possible misinterpretation of Rosso, issues about the budget plans and museum capacity were raised.100 The two retrospectives were finally scheduled one after another. The Rodin exhibition occupied the large part of the first floor and the sculpture garden of the museum, and ran between May 1 and September 8, 1963. The retrospective of Rosso opened less than one month later, and was accommodated in a room on the third floor of the museum, next to the exhibition devoted to Hans Hoffmann.101 The exhibition of the Italian sculptor was necessarily smaller in size than the one devoted to Rodin. Many reasons concurred to create this discrepancy, including the larger availability of Rodin’s works in the United States and the reduced body of work realized by Rosso. The final selection consisted of twenty-eight sculptures and five drawings. The loans largely came from Peridot Gallery and the few American private collectors who had acquired Rosso’s sculptures after the retrospective held in 1959, including Joseph H. Hirshhorn. Harry and Lydia Winston were the only prominent collectors who didn’t participate in the project. A letter in MoMA archives attests to the attempt to ask for the loan of one unidentified sculpture.102 Most likely, the conditions imposed by the Winstons were too demanding and expensive to finalize the loan. Selz integrated the group of works in the United States with a targeted selection of sculptures borrowed from Italian institutions and collectors. In this respect, the loan process took a lot of time and effort. As detailed in the reconstruction included in the appendix of this article, the curator often had to change his mind according to the inclination of the private and public lenders to accommodate his requests. Despite the several turns and revisions, all the loans were finally accomplished. Nevertheless, only one entry in the curator’s wish list remained unattained. Femme à la voilette [Lady with a Veil]—the famous impression of a veiled lady which the artist first fixed in plaster in 1895—was among the most prominent Rosso sculptures which Selz wanted to include and inexhaustibly chased down (Fig. 3).103

Medardo Rosso, “Femme à la voilette”, 1905 c.[1895].Wax over plaster.

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna.

The troubled relationship held with the heirs of Medardo Rosso impacted on the circumstances of the search of an available version of Femme à la voilette and forced Selz to contact potential lenders at short notice. Danila Rosso Parravicini, the grand-daughter of the artist, had already been contacted in early 1963, to check the availability of six drawings, but there was no response.111 When she denied the loan of the wax of Femme à la voilette held in the collection of Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, Palma Bucarelli, the museum’s director, offered instead to use her influential authority to reach out to the family of the artist, and endorse the prestige of the initiative.112 Rosso Parravicini replied to Bucarelli and confirmed the availability of a wax of Femme à la voilette and the works on paper requested a few months earlier.113 When a direct contact was established, Selz asked the Italian Cultural Institute in New York to send a formal letter to support the loan request.114 The art historian Luciano Caramel, who had just started assisting the Rosso family, also facilitated the connection, and helped the exhibition curator secure the loan of the drawings, which were reduced from six to three.115 Throughout the summer of 1963, what looked like an easy process took an unexpected turn. The family expressed concerns about the danger of a long travel for the sculpture, due to the fragility of the wax.116 They offered other works in return, but different versions had already been borrowed elsewhere.117 A few questions were also raised about the insurance policy, which looked insufficient.118When, in mid-August, Rosso Parravicini confirmed the availability of the drawings, it was too late. To reduce the costs and the bureaucracy of the export, all the works from Italy were scheduled to be shipped all at once, and there was no room to modify the procedure or to arrange a separate shipment.119

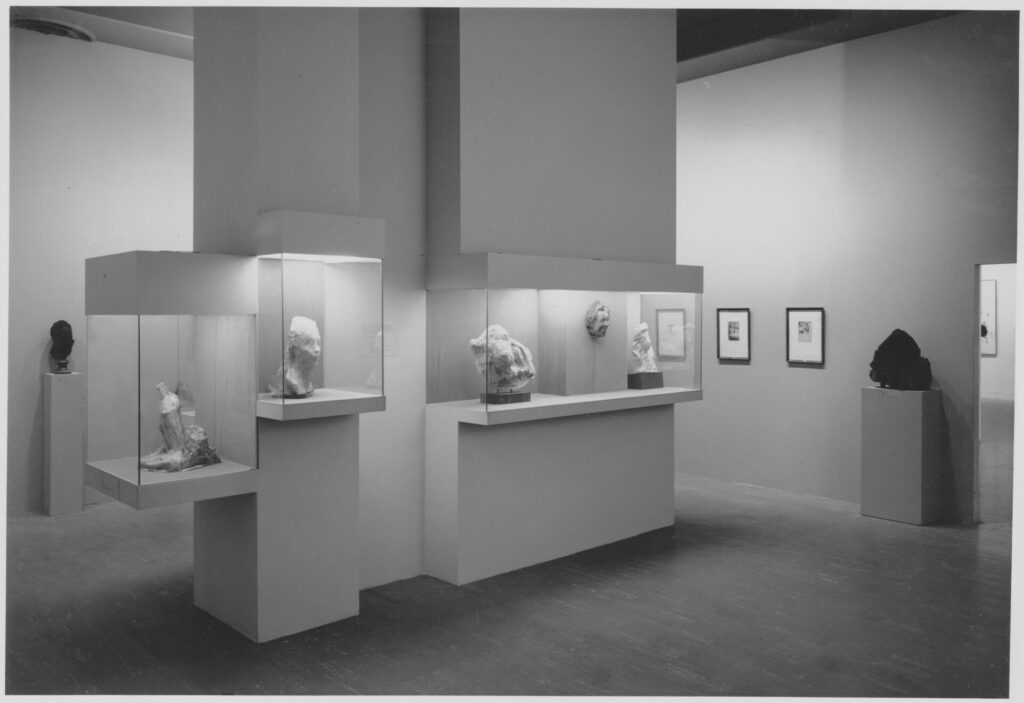

The final display of the exhibition in the room on the third floor of the museum followed the early wishes expressed by Scolari Barr, when she congratulated Selz for the decision to separate it from the Rodin retrospective: “The best thing the Museum could do with Rosso,” the scholar wrote, “would be to give him a small jewel-like show with carefully studied bases (from the point of view of height) and very attentive lighting.”120 (Figs. 4-5) The installation of the exhibition stemmed from the conversations between Selz, Scolari Barr, Seitz, and Alicia Legg, who worked at the Museum of Modern Art as assistant curator and installer.121

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

The art handlers first re-used and adjusted some pedestals which had already been fabricated for the Rodin exhibition.122 Several works had been detached from their bases, especially the ones shown in the built-in gallery case, including a few key loans from Italian museums, such as Madame X.123 New pedestals were designed to accommodate the sculptures which were displayed along the walls of the room.124 William C. Seitz oversaw the installation and was extremely careful about the preservation of the waxes. He discussed with Scolari Barr the point of view from which each single sculpture should be seen and the lighting system, in order to accentuate the texture of the surfaces, yet avoid a theatrical effect.125 Among all the sculptures, Scolari especially pointed out L’uomo che legge [Man Reading] and Yvette Guilbert as the most difficult to install, emphasizing the importance to place the former “beneath eye-level with a light coming from above,” and the latter “above eye level with light hitting from beneath and also with some light at the back.”126 The resulting installation, as documented by the photographs, was quite impressive and looked strikingly modern in the great variety of solutions by which the sculpture were displayed in the space and lit. Scolari Barr shared her appreciation with Danila Rosso Parravicini, who didn’t view the exhibition, mentioning the perfection of the lighting and the color of the background against which the waxes were installed, which consisted of “a light, very pale green, almost grayish.”127

- Informing a legacy: “All Rosso’s “projection” is into the 20th”

As it was previously mentioned in regard to her effort to scale down the issue of the relationship between Rosso and Rodin, Margaret Scolari Barr was convinced that the legacy of the Italian sculptor lay in the art of the 20th century: “All Rosso’s “projection” is into the 20th and whether he influenced the Balzac or not is quite beside the point.”128 Her interpretation informed the monograph and the presentation of the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, as attested by the book introduction and the wall-text of the exhibition, in which Selz emphasized how “the dematerialization and fluidity of his form which link it to the surrounding atmosphere make Rosso’s sculpture most relevant to our sensibility today.”129

The joined effort of the monograph and the exhibition to champion Rosso’s legacy in the modernism of early 20thcentury, as well as the resonance with contemporary sensibility, was largely discussed by reviewers and commentators. Stuart Preston welcomed the show and the book as the opportunities for a final reassessment of the historic and aesthetic significance of Rosso’s “intensely private and radical” work.130 The sculptor was hailed as “revolutionary” by Hilton Kramer in Arts Magazine, and “prophetic” in the brief presentation of the book among the forty recommendations for Christmas in Art in America.131 The anonymous reviewer who praised the exhibition in Time magazine, defined Rosso as a “rebel” and pointed out how his increasingly reductionist formal solutions, culminating in Madame X, presaged Picasso and Brancusi.132 Even skeptical reviewers, such as Thomas B. Hess and Sidney Tillim, who didn’t fully accept the interpretation of the artist’s work as radical and still found unresolved ambiguities and inconsistencies, couldn’t help but agree with Scolari Barr and Selz in considering the complexity of his art, which embraced the transient within a sense of “sensitized materiality,”133 and asserting his pioneering role in prefiguring Brancusi and the early 20th century avant-garde.134 In Italy, too, the double initiative of the book and the exhibition didn’t go unnoticed, and was extensively illustrated and praised as a watershed moment in the appreciation of Rosso in the monthly magazine Emporium.135 The editor of the book section of the monthly magazine D’Ars Agency hailed the book of Scolari Barr for the depth of scholarship and the quality of the illustrations.136 The exhibition was signaled as a prominent event in specialized magazines such as Domus.137

Among the reviews, two articles especially stand out. The first was authored by Dore Ashton, who had already positively reviewed the exhibition at Peridot Gallery in 1959. The art critic followed and expanded the interpretation elaborated by Margaret Scolari Barr and briefly surveyed the whole development of Rosso’s career in order to demonstrate that “it would be foolish to repeat the mistakes of past critics—many of whom with blatant insensitivity misunderstood Rosso’s unique personality—by bracketing him with the Impressionist painters and leaving it at that. Rosso’s relatively brief creative career, from 1882 to 1907, resulted in a group of sculptures that in many ways herald both the Expressionist and abstract sculptures that appeared later in the twentieth century.”138 The latter commentary was written by Max Kozloff, who took Scolari’s and Ashton’s assumptions to extremes, to the extent that his interpretation was the most radical at that time. Building upon the artist’s undeniable incorporation of pictorial elements into the practice of sculpture, Kozloff contended that Rosso didn’t merely embrace subjects or compositions which were typical of painting, but he embarked in the almost impossible task to integrate the metaphorical nature of painting—that, whatever the image depicted is, always alludes to something else—“to unwill the corporeality of sculpture,” by which he meant “to try to forget that the sculpture is a “thing”.”139 By virtue of the artist’s effort to resolve this issue, his art transcends any categories. Kozloff dismissed both Impressionism and Symbolism, with which Rosso was mostly associated. The struggle with the materiality led the sculptor to what Kozloff didn’t hesitate to define “an unprecedented conceptual identity,” immediately specifying that it would be erroneous “to think of them as muscular expressions of emotion” or “as jeux d’esprit with the substance.”140 Kozloff’s interpretation revolved especially around the mature works of the artist, such as Ecce Puer. Keeping these sculptures and Scolari Barr’s interpretation in mind, the art critic rejected the definition of “sketchy” applied to them, and contended instead that “they should rather be seen as gestating equivalents, in an inanimate material, of movement, tone, and atmosphere. In order to perceive the sensations that Rosso is thus eliciting, one has to blind oneself, in an important sense, to their physical presence. […] Eventually, out of a gummy moil, splintery crag, or melted veil, the sculptor induces a sense of the vicarious (one sees only the reference, not the object) in our experience of his image.”141 Such a vision would explain the specific interest of Rosso in using photography to revisit his sculptures. In this respect, Kozloff caught the brief mention of the artist’s photographs by Scolari Barr and hinted at an insightful interpretation of this branch of Rosso’s creativity, which could still resonate with current scholarship on the subject. The art critic’s survey resulted in two major conclusions about Rosso’s art: “One is that the image, whittled down to even less than its essentials, exists in a state of open possibility. This is attributable not to its vagueness but, on the contrary, to its preciseness, if one understands this word on Rosso’s terms as applying to the kind of statement that most opaquely shuts out analysis. We do not see a lady, much less a particular creature, but rather a tremulous state of being. Secondly, the use of wax […] is itself an analogy of Rosso’s expressive aims, as well as the one sculptural medium closest to paint. […] Finally, wax is a dubious material substance, incredibly light but unporous, for which reason it recommended itself unqualifiedly to Rosso.”142

Kozloff’s interpretation corroborated and expanded Scolari Barr’s and Selz’s appraisal of the modernity of the artist, and paved the way to the long-lasting legacy of the rediscovery of his art in the United States. After 1963, the name of the Italian sculptor gradually made its way into some of the most important texts on modern and contemporary art of the 1960s. A few occurrences are especially relevant to attest to the fortune of the artist. The openness of Rosso’s sculpture, the precise visualization of an evolving state of being, and the status of wax as a dense, yet light, material vis-à-vis the complexity of the artist’s vision, made a vivid impression on Kozloff, who resorted again to his art in 1968, in his monograph on Jasper Johns. The photograph of Enfant à la Bouchée de pain makes its appearance among the full-page plates of the book, next to Johns’s Flashlight III.143 Analyzing the artist’s concern in integrating sculpture within his painterly practice, Kozloff established a comparison with Rosso’s effort to reassess sculpture through the metaphorical allusiveness which is typical of painting. The image of a found object “decomposing into (or possibly emerging from) inchoate matter” resonated with the layers of wax by means of which Rosso expressed the environment surrounding the head of a poor child.144 The “synesthetic” sensibility brought the two artists together in the attempt to express that “the process of willed order deliquescing in a substance is more real—by contrast more appreciable—than any mere concept,”145 as well as to show “not […] what the thing consists of, in its density and texture, but what shades and luminosity it can project on the retina.”146

As attested by the comparison with Johns established by Kozloff, Rosso’s modernity was especially compelling for a generation of artist and critics dealing with the radical reconsideration of sculpture undertaken in the mid-1960s. Despite no documents bear witness to it, many artists and critics presumably visited the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art or took a look at the monograph. In this respect, I was able to reach out to the studio of Jasper Johns while I was fellow at CIMA, and asked him whether he saw the exhibition. His answer was elusive, yet significant: “I feel that I have always admired Medardo Rosso’s work but I don’t remember how or when I first became aware of it. […] I knew Margaret Scolari Barr and was aware that she had studied his work. It seems possible that I might have seen the 1963 MOMA exhibition, but I have no memory of it.”147 The discussion around Rosso was ambivalent, but never superficial. On one hand, the name of the artist was finally aligned with Rodin’s as the ultimate expression of the importance of process in making art, which was largely dismissed by the artists gravitating around and stemming from Minimalism. In the seminal article “Anti Form” in 1968, the artist Robert Morris comparatively contrasted the new tenets of sculpture, entailing a specific concern for the truth to materials, and the art of Rodin and Rosso, who “left traces of touch in finished work. Like the Abstract Expressionists after them, they registered the plasticity of material in autobiographical terms.”148 On the other hand, the art critic Jack Burnham, who championed several emerging tendencies and figures in the new avant-garde, made an arresting reference to Rosso. In the issue of November 1967 of Artforum, he published an essay about the vanishing of the pedestal in modern sculpture, which he would expand one year later in his pivotal book Beyond Modern Sculpture. 149 Reconstructing the genealogy of a new approach to sculpture, Burnham first examined Medardo Rosso and claimed that he paved the way to a trajectory which, through Rodin, Futurism, Brancusi, and Constructivism, led to the recent Minimalist and conceptual art. The life-size early cemetery monument by Medardo Rosso, titled La Riconoscenza [Gratitude] (1883), was illustrated in the article.150 Burnham focused on Rosso’s concern for “the plastic fusion between base and figure,” and positioned the artist as the precursor of the endeavor to remove any structural barrier between artwork and surrounding space, which would mark a substantial revolution of modernism and contemporary art.151

The reconstruction of Medardo Rosso’s legacy informed by the exhibition in 1963 and the monograph published in conjunction could extend further and be continued throughout the years. A thorough examination of the reception of Rosso in the second half of the twentieth century is still missing, and is beyond the scope of this article. The variety of the reactions and responses to Rosso’s work, ranging from dismissal and skepticism to the enthusiastic appreciation of its revolution, bear witness to the significance of the exhaustive investigation provided by the scholarly publication by Margaret Scolari Barr and the exhibition arranged by Peter Selz at the Museum of Modern Art. The first asserted her own right as a scholar and a critic by arguing that Rosso’s legacy resided in the art of the 20th century, and corroborated her assertion with the most scrupulous and extensive research possible at that time. The reviewers and commentators who wrote about the book and the exhibition, as well as the artists and critics who borrowed concepts and keywords from Scolari Barr and articulated them further, all proved that she was right in bringing the artist’s “informality and impetuous spontaneity”152 to the attention of her contemporaries. Each comment, occurrence and discussion marks a step in a lineage which stems from Scolari Barr’s intuition and, by virtue of the effort of Peter Selz to visualize it in the MoMA exhibition, has developed throughout the years, reaching the latest contributions on the artist and resonating with today’s sensibility. At almost sixty years from the exhibition and the publication, the words by which Scolari Barr referred to her own times could still be employed: “at a time when the “new realism” and the “new humanism” are again catchwords, if not passwords, Rosso’s sculpture has some special relevance.”153

*The article is the result of the research which I developed during my fellowship at CIMA in 2014-2015. I wish to thank Laura Mattioli, the members of the advisory committee Flavio Fergonzi and Vivien Greene, and the CIMA team, for supporting and assisting me throughout all the process. The project could have never been accomplished without the help of Danila Marsure Rosso and Guendalina Giannini Mochi, Archivio Rosso, Milan. I also wish to express my gratitude to Emily Braun, Neil Printz, and Fabio Vittucci. The research has been conducted with the support of the following people and institutions: Anna Vecchi, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio, Tortona; MoMA Archives, New York; Hannah Green, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC.

†The article is illustrated mostly with photographs taken from the book by Margaret Scolari Barr and installation views of the MoMA exhibition. Whenever possible, the reference to works by Rosso is accompanied by the number of the corresponding entries in the list of works on view in the exhibition, as is hereby reconstructed. With regard to illustrations of works, a decision was made to privilege Rosso’s drawings over his sculptures, due to the fact that the former are lesser known than the letter.

Bibliography

I mostra postuma milanese di Medardo Rosso. Milan: Edizioni Galleria Santo Spirito, 1946.

XIII catalogo d’arte: Mostra personale delle opere di Medardo Rosso. Milan: Bottega di Poesia, 1923.

20th Century Italian Art, London, Sotheby’s, October 16, 2009.

XXV Biennale di Venezia: Catalogo. Venice: Bruno Alfieri, 1950.

Annuario industriale della Provincia di Milano. Milan: Unione fascista degl’industriali della Provincia di Milano, 1937.

“Art: Rosso Re-evaluated.” Time 82, no. 15 (October 11, 1963).

Ashton, Dore. “A Sculptor of Mystical Feeling.” The New York Times 109, no. 37,227 (December 27, 1959): X17.

Ashton, Dore. “Medardo Rosso—A Long – Obscured Talent.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 85, no. 325 (November 24, 1963): 5C.

Bedarida, Raffaele, Davide Colombo, and Silvia Bignami, eds. “Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art”,” Italian Modern Art, no. 3 (January 2020): https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of-exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/.

Bignami, Silvia, and Davide Colombo, “Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and James Thrall Soby’s Grand Tour of Italy,” Italian Modern Art, no. 3 (January 2020): https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alfred-h-barr-jr-and-james-thrall-sobys-grand-tour-of-italy/.

Biografia Finanziaria Italiana: Guida degli amministratori e dei sindaci delle società anonime, delle casse di risparmio, degli enti parastatali ed assimilati, ecc. Rome: Tip. Laboremus, 1935.

Borghi, Mino. Medardo Rosso. Milan: Edizioni del Milione, 1950.

Boussamba, Jennifer. “Décès du collectionneur Paul Josefowitz.” Connaissance des arts (May 14, 2013): https://www.connaissancedesarts.com/arts-expositions/deces-du-collectionneur-paul-josefowitz-11893/.

Burnham, Jack. Beyond Modern Sculpture. New York: George Braziller, 1968.

Burnham, Jack. “Sculpture’s Vanishing Base.” Artforum 6, no. 3 (November 1967): 49-55.

Caramel, Luciano, and Paola Mola Kirchmayr, eds. Mostra di Medardo Rosso (1858-1928). Milan: Società per le Belle Arti ed Esposizione Permanente, 1979.

Caramel, Luciano. “La prima attività di Medardo Rosso e i suoi rapporti con l’ambiente milanese.” Arte Lombarda 6, no. 2 (July-December 1961): 265-76.

Chipp, Herschel B. “A Method for Studying the Documents of Modern Art.” Art Journal 26, no. 4 (Summer 1967): 369-76.

Claris, Edmond, ed. De l’impressionnisme en sculpture. Paris: Éditions de la “Nouvelle Revue”, 1902.

Contemporary Art, Milan, Sotheby’s, 25 November 2009.

Dobrzynski, Judith H. “Indianapolis Museum Buys 30 Gauguins From Swiss Collector.” The New York Times 148, no. 51,345 (November 18, 1998): E5.

du Plessix, Francine. “Books: Forty for Christmas.” Art in America 51, no. 6 (December 1963): 108-17.

“Elected by Banca Commerciale.” The New York Times 82, no. 27,501 (May 11, 1933): 25.

Elsen, Albert E. Auguste Rodin. New York—Garden City: The Museum of Modern Art—Doubleday, 1963.

Fles, Etha. “Medardo Rosso.” Elsevier’s Geïllustreed Maandschrift, no. 11 (November 1919).

Gamble, Antje K. “Exhibiting Italian Modernism after World War II at MoMA in “Twentieth Century Italian Art”.” Italian Modern Art, no. 3 (January 2020): https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/exhibiting-italian-modernism-after-world-war-ii-at-moma-in-twentieth-century-italian-art/.

Geist, Sidney. “Salut! Apollinaire.” in The Best in Arts: Arts Yearbook 6, edited by James R. Mellow (1962): 96-98.

Genauer, Emily. “Experiments of the Present Form Our View of the Past.” New York Herald Tribune (December 20, 1959).

Giedion-Welcker, Carola. Contemporary Sculpture: An Evolution in Volume and Space. New York: George Wittenborn, Inc., 1955.

Giedion-Welcker, Carola. Moderne Plastik. Elemente der Wirklichkeit; Masse und Auflockerung. Zurich: Girsberger, 1937.

Goldwater, Robert, and Marco Treves, eds. Artists on Art: From the XIV to the XX Century. New York: Pantheon Books, 1945.

“Good Design: 1954.” Arts & Architecture 71, no. 2 (February 1954): 16.

Guzzetti, Francesco. “Femme à la voilette, 1895-1910. Impressions in France, Germany, Great Britain and Italy,” in Medardo Rosso. Femme à la voilette (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2018): 41-59.

Hecker, Sharon. A Moment’s Monument: Medardo Rosso and the International Origins of Modern Sculpture.Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.

Hecker, Sharon. “Medardo Rosso’s First Commission.” Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1125 (December 1996): 817-22.

Important 19th-20th Century Sculpture, New York, Parke-Bernet Galleries, April 4, 1968.

Impressionist and Modern Art, Day Sale, London, Sotheby’s, February 2, 2005.

Impressionist and Modern Art, n. N08968, Sotheby’s, New York, March 13, 2013.

Impressionist, Modern and Contemporary Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, n. 1529, Sotheby’s, New York, February 7, 1996.

Jewell, Edward Alden. “Recent Books on Art.” The New York Times 95, no. 32,292 (June 23, 1946): 4X.

Kozloff, Max. Jasper Johns. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1968.

Kozloff, Max. “The Equivocation of Medardo Rosso.” Art International 7, no. 9 (November 1963): 46-47.

Kramer, Hilton. “‘An Ambiance … All Too Rare’.” The New York Times 120, no. 41, 224 (December 6, 1970): D29.

Kramer, Hilton. “Medardo Rosso.” Arts 34, no. 3 (December 1959): 30-37.

Kramer, Hilton. “Medardo Rosso at The Modern.” Arts Magazine 38, no. 1 (October 1963): 44-45.

Licht, Fred. Sculpture: 19th and 20th Centuries. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1967.

Lewis Gaillet, Lynée. “Museum of Modern Art’s “Margaret Scolari Barr Papers”.” Peitho. Journal of the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rethoric & Composition 22, no. 3 (Spring 2020): https://cfshrc.org/article/museum-of-modern-arts-margaret-scolari-barr-papers/.

“Louis Berizzi.” The New York Times 100, no. 34,024 (March 21, 1951): 33.

Marchi, Anna. “Notiziario: antichità.” Domus, no. 408 (November 1963): n.p.

Medardo Rosso: Impressions. London: Eugene Cremetti, 1906.

Medardo Rosso. New York: Center for Italian Modern Art, 2015.

Medardo Rosso: Ten Bronzes. New York—Lugano-London: Peter Freeman—Amedeo Porro Fine Arts, 2016.

Messer, Thomas, and H.H. Arnason, eds. Sculpture from the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Collection. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1962.

Modern and Contemporary Art, Chicago, Wright, 1 June 2003.

Mola, Paola, and Fabio Vittucci, eds. Medardo Rosso: Catalogo ragionato della scultura. Milan: Skira, 2009.

Mola, Paola. Rosso: Trasferimenti. Milan: Skira, 2006.

Mola, Paola. “Trasferimenti: fotografia e scultura nell’opera di Rosso.” L’uomo nero, no. 9 (2012): 40-61.

Morris, Robert. “Anti Form,” Artforum 6, no. 8 (April 1968): 33-35.

Nicodemi, Giorgio. “Una “epreuve unique” della “Rieuse” e due disegni di Medardo Rosso.” L’Arte 24, no. 4 (1959): 375-78.

Oral history interview with Margaret Scolari Barr relating to Alfred H. Barr, 1974 February 22-May 13. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-margaret-scolari-barr-relating-to-alfred-h-barr-13250#overview.

Page, Addison Franklin, ed. The Sirak Collection. Louisville: The Speed Art Museum, 1968.

“Painting and Sculpture Acquisitions January 1 through December 31, 1959,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art27, nos. 3-4 (1960): 1-40.

Preston, Stuart. “Art and Pathos: Medardo Rosso Shown At the Modern Museum.” The New York Times 113, no. 38,606 (October 6, 1963): X 17.

Preston, Stuart. “Museum of Modern Art Displaying 28 Sculptures by Rosso.” The New York Times 113, no. 38,602 (October 2, 1963): 38.

R.F.C. “New York: Una grande mostra di Medardo Rosso.” Emporium 139, no. 830 (February 1964): 68-71.

“Ricevuto e visto.” D’Ars Agency 5, no. 2 (February 1964): 174.

Ritchie, Andrew C., ed. Sculpture of the Twentieth Century. New York: The Museum of Modern Art—Simon and Schuster, 1952.

Ritchie, Andrew C. Sculpture of the Twentieth Century. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1952.

Rudikoff, Sonya. “New York Letter.” Art International 6, no. 9 (November 1962): 60-63

Schiff, Bennett. “In the Art Galleries.” New York Post (December 20, 1959): M12

Scolari Barr, Margaret. “Medardo Rosso and His Dutch Patroness Etha Fles.” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 13 (1962): 217-251.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. Medardo Rosso. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1963.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. ““Our Campaigns”.” The New Criterion (Summer 1987): 23-74.

Scolari Barr, Margaret. “Reviving Medardo Rosso.” Art News 58, no. 9 (January 1960): 36-38, 66-67.

Selz, Peter, ed. New Images of Man. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1959.

Soby, James Thrall, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr, eds. Twentieth-Century Italian Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949.

Soffici, Ardengo. Medardo Rosso. Florence: Vallecchi, 1929.

Somarè, Enrico, ed. Raccolta Enrico Mascioni. Milan: Galleria Pesaro, 1931.

Staudacher, Elisabetta, ed. Capitani di un esercito: Milano e i suoi collezionisti. Milan: Gallerie Maspes, 2017.

“Stefano Berizzi.” The New York Times, vol. CX, no. 37,536 (October 31, 1960): 31.

Taylor, Joshua C., ed. Futurism. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1961.

T.B.H. [Thomas B. Hess]. “Reviews and Previews: Medardo Rosso.” Art News 62, no. 7 (November 1963): 14.

The first exhibition in America of sculpture by Medardo Rosso, 1858-1928. New York: Peridot Gallery, 1959.

Tillim, Sidney. “Month in Review.” Arts Magazine 38, no. 2 (November 1963): 28-31.

Treves, Marco, “Maniera, the history of a word,” Marsyas 1 (1941): 69-88.

W.R. “The Hirshhorn Collection at the Guggenheim Museum.” Art International 6, no. 9 (November 1962): 34-37.

- Peter Selz, typewritten letter to Palma Bucarelli, April 26, 1963, The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, [729.2]. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York (from now on, the citation will be as follows: MoMA Exhs., [exh.#.folder]. MoMA Archives, NY).

- Robert Goldwater, Marco Treves, eds., Artists on Art: From the XIV to the XX Century (New York: Pantheon Books, 1945).

- Edward Alden Jewell, “Recent Books on Art,” The New York Times 95, no. 32,292 (June 23, 1946): 4X. On the book’s legacy, see Herschel B. Chipp, “A Method for Studying the Documents of Modern Art,” Art Journal 26, no. 4 (Summer 1967): 371.

- “Foreword,” in Goldwater, Treves, Artists on Art, cit., vii.

- See the biography available at the following link: http://marcotreves.blogspot.com/.

- Marco Treves, “Maniera, the history of a word,” Marsyas, vol. 1 (1941): 69-88.

- Robert Goldwater, “Introduction,” in Goldwater, Treves, Artists on Art, cit., 11.

- Edmond Claris, ed., De l’impressionnisme en sculpture (Paris: Éditions de la “Nouvelle Revue”, 1902): 321-26, translated as Medardo Rosso, “The Aims of Sculpture,” in Goldwater, Treves, Artists on Art, cit., 329-30.

- Ibid., 329.

- Ibid., vii.

- James Thrall Soby, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Twentieth-Century Italian Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949): 7, 33. On the genesis and significance of the exhibition, see the special issue of Italian Modern Art, Raffaele Bedarida, Davide Colombo, Silvia Bignami, eds., “Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art””, Italian Modern Art, no. 3 (January 2020).

- Andrew C. Ritchie, Sculpture of the Twentieth Century (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1952): 15, 17

- Ibid., 17, 34-35.

- Ibid., 66-67.

- Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 11 – December 7, 1952; Chicago, The Art Institute, January 22 – March 8, 1953; New York, The Museum of Modern Art, April 29 – September 7, 1953.

- Andrew C. Ritchie, ed., Sculpture of the Twentieth Century (New York: The Museum of Modern Art—Simon and Schuster, 1952): 44.

- The American edition belonged to the series of books “Documents of Modern Art,” directed by Robert Motherwell, see Carola Giedion-Welcker, Contemporary Sculpture: An Evolution in Volume and Space (New York: George Wittenborn, Inc., 1955).

- Carola Giedion-Welcker, Moderne Plastik. Elemente der Wirklichkeit; Masse und Auflockerung (Zurich: Girsberger, 1937).

- Giedion-Welcker, Contemporary Sculpture, cit., 12.

- Ibid., 13-17, 77

- Margaret Scolari Barr, handwritten notes to William C. Seitz, October 28, 1963, MoMA Exhs., [729.4], MoMA Archives, NY.

- Press Release no. 108, October 21, 1963, MoMA exhibition records, 729. Medardo Rosso, 1858-1928 [MoMA Exh. #729, October 2-November 23, 1963], https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3437. The notes are dated “Monday 28,” which should read as October 28, a few days before the lecture, and addressed to a certain Bill, who should be identified as William C. Seitz.