Introduction

A brief overview of the third issue of Italian Modern Art dedicated to the MoMA 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, including a literature review, methodological framework, and acknowledgments.

Another History: Contemporary Italian Art in America Before 1949

This essay looks at modern Italian art circulating in the United States in the interwar period. Prior to the canonization of recent decades of Italy’s artistic scene through MoMA’s 1949 show Twentieth-Century Italian Art, the Carnegie International exhibitions of paintings in Pittsburgh were the premier stage in America for Italian artists seeking the spotlight. Moreover, the Italian government actively sought to promote its own positive image as a patron state in world fairs, and through art gallery exhibitions. Drawing mostly on primary sources, this essay explores how the identity of modern Italian art was negotiated in the critical discourses and in the interplay between Italian and American promoters.

While in Italy much of the criticism boasted a self-assuring “untranslatable” character of national art through the centuries, and was obsessed by the chauvinistic ambition of regaining cultural primacy, especially against the French, the returns for those various artists and patrons who ventured to conquer the American art scene were meager. Rather than successfully affirming the modern Italian school, they remained largely entangled in a shadow zone, between the glaring prestige of French modernism and the glory of the old masters (paradoxically enough, the only Italian “retrospective” approved by MoMA before 1949). Some Italian modernists, such as Amedeo Modigliani, Giorgio de Chirico, and Massimo Campigli, continued to be perceived as French, while the inherent duality and ambiguity in the critical discourse undergirding the Novecento and the more expressionist younger generation – which struggled to conflate Italianism and modernity, traditionalism and vanguardism – made the marketing of an Italian school more difficult. Therefore, despite some temporary critical success and sales, for example for Felice Carena, Ferruccio Ferrazzi, and Felice Casorati, the language of the Italian Novecento was largely “lost in translation.”

Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and James Thrall Soby’s Grand Tour of Italy

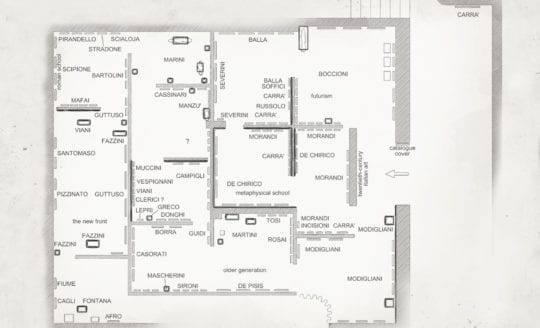

From May to June 1948, and with the approval of MoMA’s trustees, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and James Thrall Soby did a “grand tour” of Italy, visiting artists, collectors, critics, dealers, museum, and galleries in Milan, Bergamo, Brescia, Rome, Venice, and Florence. Along the way they saw the Fifth Quadriennale in Rome and the Twenty-Fourth Venice Biennale; these, the most important art events of the time, would prove major sources for Barr and Soby as the curators of the 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art. The mission of the journey was double: selecting artworks for the show, and acquiring artworks for MoMA’s collection, which was sparse in its Italian modern art holdings.

This essay analyzes how and why Barr and Soby worked to shape a history of Italian modern art within the international context of modernism according to the stylistic genealogy of art that Barr had, since 1936, proposed at MoMA. The details of whom they met; which works they saw and selected, borrowed or purchased; and which works weren’t available makes it possible to better understand the framework of the exhibition. In effect, Barr and Soby’s approach was ambivalent: their desire for autonomy and their strategy of not involving public institutions allowed them to build direct relationships with artists and private collectors. Twentieth-Century Italian Art was an operation of cultural diplomacy that needed to go through official channels, even as the curators insisted on selecting works based primarily on their artistic value and high quality, without prioritizing the political affiliation of the artists. Barr and Soby considered the new democratic and political order in Italy after the end of Fascism an indispensable prerequisite for an artistic “renaissance,” which merited the organization of an exhibition at MoMA; they often agreed on selected artworks, and their personal tastes and interests emerged during the process.

“Positively the only person who is really interested in the show”: Romeo Toninelli, Collector and Cultural Diplomat Between Milan and New York

Romeo Toninelli was a key figure in the organization of Twentieth-Century Italian Art, and given the official title of Executive Secretary for the Exhibition in Italy. An Italian art dealer, editor, and collector with an early career as a textile industrialist, Toninelli was not part of the artistic and cultural establishment during the Fascist ventennio. This was an asset in the eyes of the James Thrall Soby and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who wanted the exhibition to signal the rebirth of Italian art after the presumed break represented by the Fascist regime. Whether Toninelli agreed with this approach we do not know, but he played a major part in the tortuous transatlantic organization of the show. He acted as the intermediary between MoMA curators and Italian dealers, collectors, and artists, securing loans and paying for the shipping of the artworks. He also lent several works from his collection, and arranged for the printing of the catalogue. A recent collector and gallery owner, Toninelli was mistrusted by many Italian critics and collectors, who suspected him of having commercial motives. Yet he arranged the practical side of the operations while intervening little in the decision-making about which artists to include – exactly as MoMA wanted.

Analyzing Toninelli’s role in organizing the pioneering display of Italian modernism at MoMA provides important insights into transatlantic cultural exchanges between Italy and the U.S. in the postwar period, and illuminates critical fractures of the Italian art system in the aftermath of Fascism. Were native-born critics and artists obliged to hand the narrative of modern Italian art over to outsiders who had not been compromised by the Fascist regime, or were they entitled to an account independent from the modernist vulgate promoted by MoMA?

Neocubism and Italian Painting Circa 1949: An Avant-Garde That Maybe Wasn’t

This essay considers the category and style of “Neocubism” within the Italian avant-garde of the 1930s and 40s. A term applied to artists such as the Corrente group and Il Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, “Neocubism” became loaded with political and aesthetic connotations in the last years of Fascism and the first of the postwar period. These young Italian artists were deeply influenced by the work of the Cubists, but especially that of Pablo Picasso. His 1937 Guernica became an ideological touchstone for a new generation that had endured Fascism and joined in the partisan fight against Nazi occupation. This essay seeks to disentangle this knotted legacy of Cubism and point to the rapidly changing stakes of the surrounding discourse, as Italy transitioned from Fascist state to postwar Republic to Cold War frontier. Adding nuance and diversity to a term so often applied monolithically will allow for a truer sense of Italian Neocubism when and if it was manifested throughout this period.

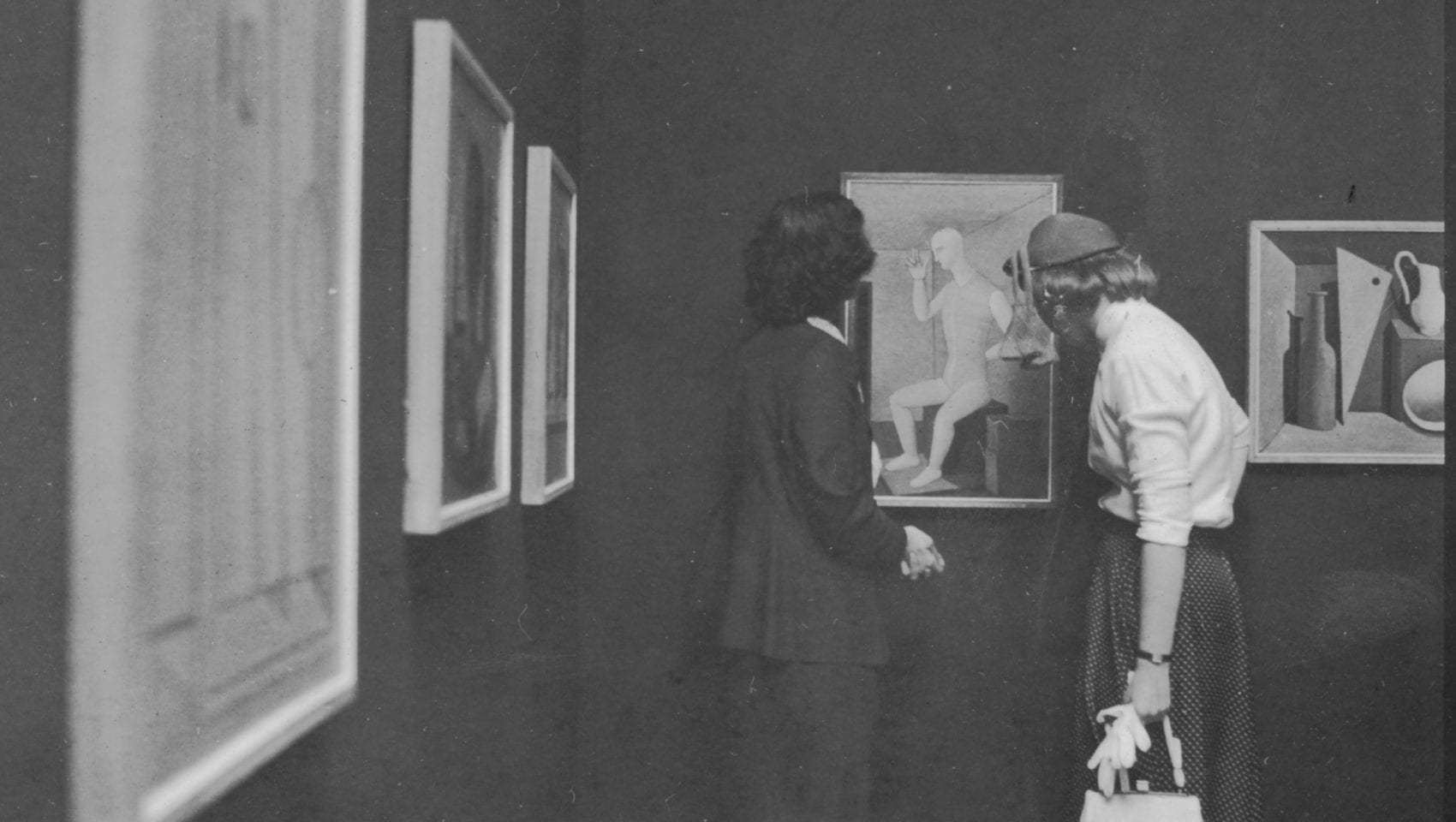

Exhibiting Italian Modernism After World War II at MoMA in “Twentieth-Century Italian Art”

Foregrounded as a kind of exploratory survey of work outside of the “two formidable counter-attractions in Europe—the Parisian present and the Italian past,” Twentieth-Century Italian Art curated a particular view of Italian modern art. The 1949 exhibition at MoMA would become the precedent for international investigations of Italian modern and avant-garde art, and one that represented Italy as a modern democracy. In part to uphold this idea, curators Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and James Thrall Soby presented Italian modernism as apolitical aesthetic experiments.

In part, the works were selected by using Fascist art world contacts and exhibitions as guides, which helped shape Barr’s coalescing vision for a modernist hegemony. The installation also foregrounded a depoliticization of the cultural production of the former combatant country. The works were not presented in the more innovative manner seen in exhibitions like the prewar We Like Modern Art (1940–41) or the wartime Road to Victory (1942), which gained inspiration from the same avant-garde exhibition models that Fascist exhibitions like the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista (1932–34) had evoked. Rather, the exhibition was installed in a more deadpan manner, with most works displayed with ample space at similar heights. Precedent for this installation style can be seen in MoMA as well as in Italy, particularly in the presentations at the Rome Quadriennale of the 1930s and 40s. Barr and Soby were able to visually reframe the production of Italian artists as part of a transatlantic modernist project, rather than an Italian Fascist one.

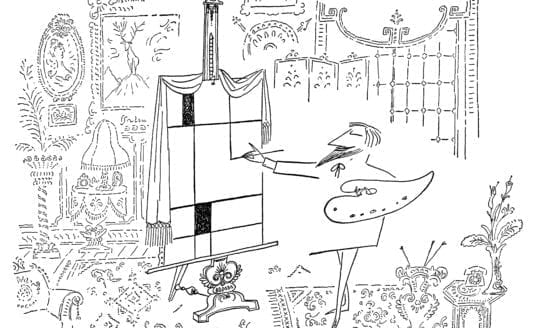

Saul Steinberg, MoMA, and the Unstable Cultural Field

This essay addresses the U.S. cultural field of the late 1940s as an unstable territory in which the protocol for evaluation and judgment of the literary as well as visual arts underwent considerable and radical revision. It argues for the identification of a brief but discrete period lasting from the end of World War II to the closure of the decade, characterized by pronounced uncertainty and tension over what forms and practices should be understood as legitimate. It traces the onset of this moment of instability in relation to modernism, transatlantic exchange, and the institutions of culture, using the particular example of Saul Steinberg (1914–1999) and his relationship to the legacy of Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). Steinberg emigrated from Italy to the U.S. during the war, having been interned as a Jew under Mussolini. A trained architect, fluent in the visual grammar of European interwar modernism, Steinberg reinvented himself in postwar America as an artist and illustrator. Steinberg proved himself exceptionally capable of traversing high and low culture, commercial and restricted fields, by virtue of his ability to negotiate the cultural field. By examining his engagements with Mondrian and the New York art world of the late 1940s, we stand to learn something new not only about him, but about the instability of the field at that time.

“Friendly Competition”: A Network of Collecting Postwar Italian Art in the American Midwest

Collecting art is usually seen as an individual occupation, motivated by personal passion, desire to possess, and economic investment. This paper suggests that there are social aspects of collecting that need to be considered as well. These aspects can lead to a form of “friendly competition” among local collectors. This is evident in the case of St. Louis and the collecting of postwar Italian art. Through interviews with family members and research into archival materials, this paper traces the identities of collectors (Pulitzer, Weil, Shoenberg, May, and Bernoudy) and examines the mechanisms through which productive rivalries arose. It concentrates on the collections of the Kemper Art Museum and the Saint Louis Art Museum, where one finds similar-looking works by Alberto Burri, Afro, and Marino Marini, made in the same years and bought by local collectors in the same period.

What were the relationships and connections that developed between St. Louis collectors of postwar art? How did this web develop into a community or social group, and how did this lead to donations of works to local museums? What were the relationships between these collectors and the 1949 MoMA exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art and its organizers? How did MoMA shows, prepackaged for further exhibition in the Midwest, influence collectors’ tastes? How did travel abroad to exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale affect acquisition habits? Whose opinion did the collectors trust and which dealers did they buy from? Such questions and their ramifications are discussed before the paper concludes with a consideration of the process through which St. Louis collectors were identified in Harold Rosenberg’s 1965 Esquire article on tastemakers in the field of contemporary art.

It’s a Roman Holiday for Artists: The American Artists of L’Obelisco After World War II

L’Obelisco was among the most international of galleries in Rome (1946–81). Its owners, Gaspero del Corso and Irene Brin, established particularly close relationships with the United States starting in 1946, when the gallery opened. They organized the first European exhibition of Robert Rauschenberg, in 1953, and shows of Eugène Berman, Roberto Matta, Saul Steinberg, Ben Shahn, and Alexander Calder, among many others. In 1957, they facilitated the first European retrospective dedicated to Arshile Gorky, with a catalogue that included a preface by Afro.

This paper addresses the presence in Italy, from World War II through the 1950s, of artists from the U.S. including exiles who had fled there from elsewhere in Europe during the conflict. Artistic, commercial, and political factors intertwined and favored the concentration of American artists in Italy after the Liberation. Starting with their management of the small gallery La Margherita (1943–45), the del Corso couple were a reference point for all sorts of visitors from the U.S., including intelligence agents. Thanks to the complicity of one such agent, the journalist and antiquarian Peter Lindamood, and of the gallerist Alexander Iolas, the “Fantasts” section of the MoMA exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art took shape. In this complex scenario, the program of exhibitions held at L’Obelisco appears to be very much in line with the cultural policy of the U.S. State Department, as indicated also by the personal and professional relationship of the del Corsos with L.P. Roberts, dynamic director of the American Academy in Rome from 1946 to the end of the 1950s. Furthermore, the role of Irene Brin cannot be underestimated. She was a prominent fashion journalist, interested in cinema, photography, and fashion, and her international connections (especially after she became Rome Editor of Harper’s Bazaar in 1952) attracted a heterogeneous mix of foreign visitors to the gallery, who were also drawn to Rome by the thriving Neorealist artistic movement and new job opportunities through Cinecittà for Hollywood productions. For some artists coming from the U.S., Rome was a decisive destination: Matta, Berman, and Tchelitchew moved to the city; Calder worked in Italy repeatedly; and, as is well known, Rauschenberg encountered in the capital a major influence on his own works from the 1950s, Burri’s Sacks.

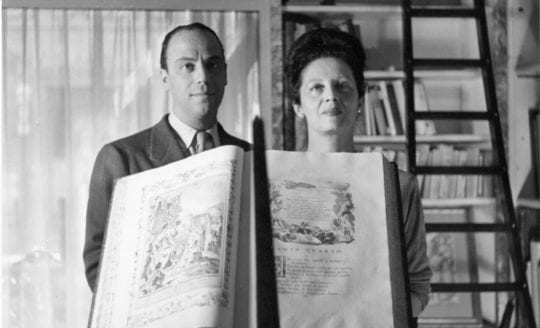

On Giorgio Morandi: Milton Glaser in Conversation with Matilde Guidelli-Guidi and Nicola Lucchi

This is the transcript of a wide-ranging interview with artist and graphic designer Milton Glaser that took place at CIMA in 2016. Glaser discusses his experiences as a Fulbright grantee in Bologna, Italy, where he enrolled in an etching class taught by Giorgio Morandi at the city’s Accademia di Belle Arti. The interview provides insights into Morandi’s personality and teaching method, into Glaser’s consideration of Morandi’s oeuvre, and into the designer’s own artistic vision.