It’s a Roman Holiday for Artists: The American Artists of L’Obelisco After World War II

Ilaria Schiaffini Ilaria Schiaffini Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of-exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/

L’Obelisco was among the most international of galleries in Rome (1946–81). Its owners, Gaspero del Corso and Irene Brin, established particularly close relationships with the United States starting in 1946, when the gallery opened. They organized the first European exhibition of Robert Rauschenberg, in 1953, and shows of Eugène Berman, Roberto Matta, Saul Steinberg, Ben Shahn, and Alexander Calder, among many others. In 1957, they facilitated the first European retrospective dedicated to Arshile Gorky, with a catalogue that included a preface by Afro.

This paper addresses the presence in Italy, from World War II through the 1950s, of artists from the U.S. including exiles who had fled there from elsewhere in Europe during the conflict. Artistic, commercial, and political factors intertwined and favored the concentration of American artists in Italy after the Liberation. Starting with their management of the small gallery La Margherita (1943–45), the del Corso couple were a reference point for all sorts of visitors from the U.S., including intelligence agents. Thanks to the complicity of one such agent, the journalist and antiquarian Peter Lindamood, and of the gallerist Alexander Iolas, the “Fantasts” section of the MoMA exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art took shape. In this complex scenario, the program of exhibitions held at L’Obelisco appears to be very much in line with the cultural policy of the U.S. State Department, as indicated also by the personal and professional relationship of the del Corsos with L.P. Roberts, dynamic director of the American Academy in Rome from 1946 to the end of the 1950s. Furthermore, the role of Irene Brin cannot be underestimated. She was a prominent fashion journalist, interested in cinema, photography, and fashion, and her international connections (especially after she became Rome Editor of Harper’s Bazaar in 1952) attracted a heterogeneous mix of foreign visitors to the gallery, who were also drawn to Rome by the thriving Neorealist artistic movement and new job opportunities through Cinecittà for Hollywood productions. For some artists coming from the U.S., Rome was a decisive destination: Matta, Berman, and Tchelitchew moved to the city; Calder worked in Italy repeatedly; and, as is well known, Rauschenberg encountered in the capital a major influence on his own works from the 1950s, Burri’s Sacks.

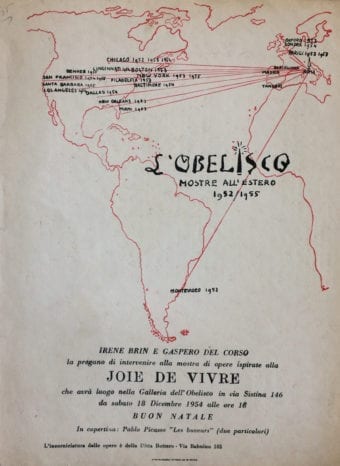

L’Obelisco (1946–81) was the first gallery to open in Rome after World War II, under the direction of the couple Gaspero del Corso and Irene Brin, and the most characterized by relations with the United States (figures 1a–1b). From November 1946 to December 1959, over thirty exhibitions of overseas artists were held at L’Obelisco, if we include exiles who fled Europe during World War II – an astounding number. Also remarkable was the gallery’s timeliness in staging the Italian debuts of some of the most highly esteemed contemporary artists: Salvador Dalí in 1948; Roberto Matta in 1950; Saul Steinberg in 1951; and Yves Tanguy in 1953, the same year as Robert Rauschenberg’s first European exhibition, at L’Obelisco. In 1956, the first Italian solo exhibition of Alexander Calder was held at the gallery, which also organized, in the following year, the first European retrospective of the late Arshile Gorky (1904–1948).

The preeminence of L’Obelisco in this context is much mentioned, but this paper draws on recently published research and new archival acquisitions1 to provide new insight into the presence of U.S. artists at the gallery during the 1950s. That decade was a pivotal period for both the dissemination of American art in Italy and the “export” of Italian art to the U.S. – greatly encouraged by the seminal 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In fact, L’Obelisco contributed significantly in the selection presented at MoMA. When Alfred H. Barr Jr., and James Thrall Soby came to Rome in the spring of 1948 to choose the exhibition’s artworks, they considered L’Obelisco as their main reference for the Roman School (Luigi Bartolini, Marcello Muccini, and Renzo Vespignani), as well as for Afro.2 The Del Corsos’ influence on the arrangement of the “Fantasts” section of Twentieth-Century Italian Art was, in comparison, more indirect, but arguably more pervasive.

Thus, the history of L’Obelisco traces the closely connected artistic exchanges, commercial transactions, and broader political-cultural trends that led to the hegemony of U.S. art relative to Italian during the Cold War period. The most remarkable impact of this process was the Grand Prize for painting awarded to Rauschenberg at the 1964 Venice Biennale.

U.S. Visitors to the Roman Art World After World War II

“At the end of World War II artists from all over the U.S. began to head for Italy where, for the past six years, they have swarmed the hillsides and made Rome the rival of Paris as art headquarters,” reads a Life magazine article from 1952.3 The possibility of examining first-hand the extraordinary remains of antiquity, freed from the rhetoric of Fascism, and the perception of a new vital energy following the devastation of war, along with the affordability of travel and renowned Italian musts (food, wine, and weather), conferred a newly attractive identity to the Belpaese, and in particular to its capital.4 Photographs in magazines animated the monumental ruins of ancient and baroque Rome, turning them into fascinating settings for glamorous living. The city became a place where aristocratic offspring met with writers, artists, and Hollywood actresses and actors, who all enjoyed a carefree daily life alongside models, set designers, and entrepreneurs. According to a Time magazine article, “it is probably the combination of beauty and stability that has made Rome irresistible to travelers in the unstable world of 1949.”5 Also contributing to its appeal were developments in the film industry, as American filmmakers came to Italy for the availability of highly specialized low-cost craftsmen. The promotion of Italian-made fashion was an additional factor in the flow of visitors, especially from the U.S., whose marvelous experience of the dolce vita was perfectly captured by Audrey Hepburn and Gary Cooper in the film Roman Holiday (1953).6

Several personalities in the Roman art world played a mediating role with respect to Americans in the years immediately following the war, among them the art critic Lionello Venturi and the painter Corrado Cagli, who, after Fascism, returned from exile in the U.S. The first important Italian artist to mention is Afro. In frequenting the American Academy in Rome under the direction of the dynamic Laurance P. Roberts, he became a close friend of both Philip Guston, who first came to the city in 1948 on the occasion of the Prix de Rome,7 and Patrick Kelleher, who was a fellow there, studying Baroque art from 1946–48, and became, in 1949, director of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, replacing Andrew Ritchie. The latter, who moved on to New York’s MoMA, was another important contact for Afro, and would, among other things, write the catalogue of his solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1956.8 In Rome Afro also met Catherine Viviano, with whom he established a personal and long-lasting relationship. Her New York gallery, which opened in 1950, was at the center of initial, crucial import-export exchanges between Rome and New York, including the introduction of Abstract Expressionist painters in Italy.9 Also to be noted are the interactions of the critic Gabriella Drudi; the artists Ettore Colla, Piero Dorazio, and Toti Scialoja; and the poet Emilio Villa with U.S. contacts,10 which facilitated the circulation of American abstract painting in Italy through the Gruppo and Fondazione Origine and the magazine Arti visive.

Many Americans resided in Rome for a more or less long period, for instance the art journalist and photographer Milton Gendel, who settled in Rome in 1950 and some years later began to report from Rome on the novelties of the art world for the magazine Art News.11 Another personality connected with the Roman art world was the African-American writer William Demby, who lived in a sort of artist’s commune with Muccini and Vespignani, and married Lucia Drudi, Gabriella’s sister.

The Italian-American artists who settled in Rome after WWII didn’t form a national group, as certain of their predecessors had done in the nineteenth century. Their experiences varied from one individual to the next, but for the most part these artists found it difficult to work in Rome and therefore they remained more connected to critics and gallerists at home. In essence, according to Peter Benson Miller, Rome remained for Italian-American artists a foreign locale.12 Among them, Nicolas Carone should be mentioned; he was granted a residency at the American Academy from 1947–51 and joined the circle of Via Margutta before returning to New York to work as assistant director at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery.13 That American gallery is indeed a main point of reference for the art exchanges between Rome and New York during this period, along with the Catherine Viviano Gallery. At the Stable Gallery, Carone oversaw an Alberto Burri exhibition in the fall of 1953; Carone would later claim it was he who introduced the Italian artist to America.14 Salvatore Meo moved to Rome from Philadelphia in 1951, remaining there for the rest of his life. Close to the Fondazione Origine, he was the U.S. art director for Arti visive, and in Rome was in touch with Burri, Colla, and Carone.

After the mid-1950s, two more Italian-Americans who strengthened connections between the Roman and American art worlds were Salvatore Scarpitta and Conrad Marca-Relli.15 Through the gallery La Tartaruga, owned by Plinio De Martiis and inaugurated in 1954, they particularly contributed to the introduction of Abstract Expressionism in Rome. The American artist most identified with De Martiis’s gallery, however, is Cy Twombly: he moved to Rome with the help of Eleanor Ward, his dealer, and soon came into contact with De Martiis and his close associate the collector Baron Giorgio Franchetti, whose sister Tatiana would marry Twombly.

In the second half of the 1950s, La Tartaruga joined L’Obelisco in playing a central role in Rome for avant-garde American artists, hosting, in 1958, the first European solo exhibitions of Franz Kline and Twombly, in addition to, in 1959, the second Roman show of Rauschenberg.16 In 1956, events in Hungary had caused many left-wing Italian intellectuals and artists to shift towards the Western bloc, and cultural exchanges between Italy and the U.S. significantly intensified thereafter. The inauguration of the Rome–New York Art Foundation by Frances McCann in 1957 and a solo exhibition of Jackson Pollock at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna the following year marked the beginning of a new phase.

The Success of L’Obelisco Among American artists: Relations, Government Promotion, and Intelligence Operations

Until the end of the decade, L’Obelisco was undoubtedly the most appealing gallery for American artists in Rome. The increasing success of the gallery in the years immediately following the war is partly explained by the fact that it was able to intercept the various expectations of a cosmopolitan jet set eager to enjoy the Belpaese while rediscovering the primitive charm of local places and the spontaneity of residents. Irene Brin (born Maria Vittoria Rossi) was a highly cultured, brilliant polyglot; her work as a fashion journalist and prominent international proponent of Italian style won her, in 1955, the highest decoration awarded by the Italian President of the Republic.17 In 1951, she actively cooperated with Baron Giovanni Battista Giorgini to promote a seminal high fashion show at the Palazzo Torrigiani in Florence, when “made in Italy” was successfully presented to American buyers. Moreover, after becoming the Rome editor of Harper’s Bazaar in 1952, her travels with del Corso and international contacts increased notably (figure 2). 1953 is the year within which the highest number of L’Obelisco solo exhibitions of U.S. artists took place: five out of a total of thirty-one.18 That same year, the exhibition Twenty Imaginary Views of the American Scene by Twenty Young Italian Artists began touring internationally, financed by Helena Rubinstein, the cosmetics queen – another vital link between fashion and art.19 Some artists who came to L’Obelisco from America – namely, Eugene Berman, Pavel Tchelitchew, and Carlyle Brown – were linked to fashion by a rich network of commissions in New York, where they had worked as interior designers for private residencies, fashion magazines, the theater, and the ballet performing with the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Furthermore, as an extension of her professional relationships with photojournalists working in Rome on behalf of international magazines, Irene Brin was among the first in Italy to present photography exhibitions in the private art gallery setting; worth noting are the L’Obelisco displays of Herbert List, in 1949, and Brassaï, in 1962, and of the Italian photographers Pasquale De Antonis, in 1951 and 1957, and Enzo Sellerio, in 1956.20 In sum, Irene Brin took advantage of her public prominence and professional role in order to promote captivating exhibitions for an American clientele intent on discovering “Hollywood on the Tiber.”

Starting in the postwar period, the U.S. government increasingly focused on Italy in pursuing initiatives aimed at consolidating its sphere of cultural and political influence. Fellowships such as the Fulbright, which granted its first awards for U.S.-Italian travel in 1946, and the already existing Guggenheim, were particularly concentrated in the Belpaese,21 and a pivotal role in sponsoring travel to Italy was played by the American Academy thanks to the reestablishment of the Rome Prize in 1947. Laurance Roberts, the open-minded reformer in charge of that well-aged institution from 1946–59, linked the cultivation of artistic refinement to cultural diplomacy. Following Martin Brody’s advice, he transformed the Academy into a stronghold of liberal and anticommunist cultural politics in the decade after World War II.22

Cultural support was also often accompanied by intelligence agencies’ objectives, as set up during World War II.23 Following the armistice of September 8, 1943, the U.S. established extensive contacts among Italian intellectuals and deserters, who were united in more or less explicit opposition to Fascism. The first investigative and cultural support structure was the new civilian intelligence agency established in 1942 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, soon to be known as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and headed by William J. Donovan; it would carry out secret activities abroad and analyze information related to national defense (and eventually became known as the CIA).24 Moreover, one must not forget the Psychological Warfare Branch, a joint Anglo-American section of the Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ), established after the landing in Sicily and intended to coordinate propaganda efforts in recently liberated European countries. In 1953, the different branches in charge of the U.S. State Department’s international cultural and informational policies merged into the independent agency United States Investigation Services (USIS), based in embassies and consulates.25 It had a pivotal role in the “Americanization” of Italy during the Cold War.

The U.S. federal government passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act in 1944 – better known as the GI Bill – which provided, until 1956, a range of benefits for returning war veterans to aid them in readjusting to civilian life, for instance low-interest home mortgages, unemployment insurance, and financial assistance for a wide range of educational and vocational training opportunities. With this support, many veterans had the chance to visit Italy. Cultural developments were additionally produced by economic recovery programs such as the Marshall Plan, established in 1948; in the following years, select American photographers were tasked with documenting the infrastructure constructed in Italy under the plan to address wartime devastation and regenerate the national economy.26

Some protagonists of the Italy-U.S. exchange arrived in Rome through the channels of the intelligence services, and frequented La Margherita gallery before becoming part of the entourage of L’Obelisco. La Margherita was the art gallery and antiquarian bookshop run by Irene Brin as of September 1943, when she needed to support herself economically while del Corso was forced into hiding after having deserted the army following the armistice. (This latter fact might explain the origin, or at least the ease, of the del Corsos’ relations with the U.S.)

One of the first to arrive at La Margherita was journalist and antiquarian Peter Lindamood, who was then working for the Psychological Warfare Branch of the U.S. Army. Lindamood became responsible for the opening of a first channel of exporting Italian “Fantastic” art from Rome to New York. In 1945, he noticed a group of young Italian artists who exhibited together with Leonor Fini at La Margherita, and whose works would later be presented at L’Obelisco. He actively promoted their circulation in the U.S. through the very cultural and commercial channels that influenced the image of Italian Art presented in the Twentieth-Century Italian Art exhibition.

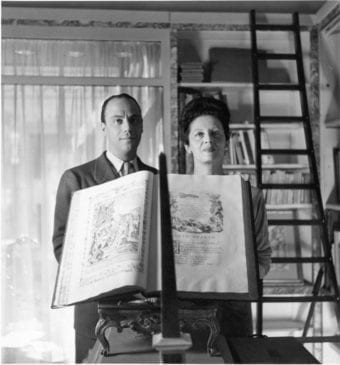

Also on the scene was the photographer Leslie Gill; employed by the magazines Town and Country and Life, he was simultaneously working, as his daughter has confirmed, for Donovan’s OSS.27 Gill, as a collector of L’Obelisco artists, was very close to the del Corso couple. Some beautiful photos taken by Gill of Irene Brin and del Corso at L’Obelisco are archived at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome (figure 3).28

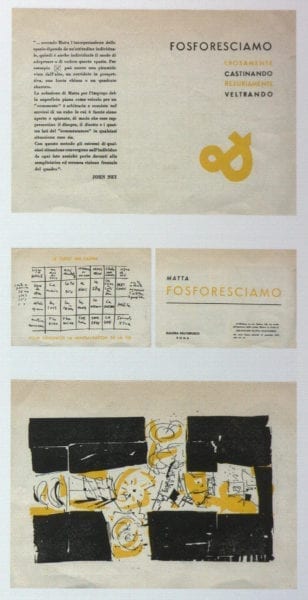

The most famous American artist of the L’Obelisco cadre engaged in intelligence activities was Saul Steinberg. Following his first participation in an art show – the group exhibit Fourteen Americans held at MoMA in 1946, Steinberg had his first solo show ever at L’Obelisco in 1951, organized by Cesare Zavattini (figures 4a–4b). As the L’Obelisco exhibit stimulated interest in the artist in Italy, Mondadori published Steinberg’s book L’Arte di vivere in 1954 (originally The Art of Living, 1949), the first of many books by the artist to be produced in Italy. Romanian by birth, Steinberg had studied architecture at the Milan Polytechnic.29 Thanks to his graphic skills and language fluency, Steinberg was a prime candidate for the Morale Operations branch of the OSS in Europe, a propaganda effort. He was first assigned to the Navy in China,30 and after a period in Africa reached Italy, passing through Naples and arriving in Rome. At the time of his show at L’Obelisco, he had already returned to New York; however, until his final discharge from the naval reserve in 1954, Steinberg could be recalled to active duty, and he was required to report his dates of travel any time he left the U.S.31

William Congdon and Bernard Childs, who exhibited at L’Obelisco, respectively, in 1953 and in 1958 (the first) and in 1952 (the second), also actively participated in the war. Enrolled in the American Field Service, a voluntary health service organized during the war, Congdon joined the invasion of Italy as an ambulance driver and continued to help civilians after the war. During the 1950s he expressed his deep sensitivity in lyrical, thick informal painting. After many stays in Italy, and in particular Venice,32 and having converted to Catholicism, he moved first to Assisi, then to nearby Buccinasco, in Lombardy, where he stayed until his death in 1998. The painter and engraver Childs, oriented instead towards abstract experimentation involving the sign, was a son of Russian immigrants. He came to Italy in 1951 through the GI Bill, having served as a quartermaster aboard the destroyer escort USS Wesson in the war. He became a friend of Burri and Enrico Donati, an Italian-American late-surrealist painter and sculptor who exhibited at L’Obelisco in 1950 and was connected to Carone and Ward.

L’Obelisco was pivotal for American artists in Rome thanks to the close relations the two owners entertained with Roberts at the American Academy, as well as with his wife Isabel; they in turn were very close to Clare Boothe Luce, the U.S. Ambassador in Rome from 1953–56.33 At the end of June 1954, del Corso phoned Isabel to try to obtain an exhibition for Ben Shahn; at the time the artist’s solo exhibition was on view at the Venice Biennale, curated by James Thrall Soby. Given the prevailing attitudes of McCarthyism in the U.S., the U.S. Pavilion’s official emphasis on a Russian-American artist and anarchist placed heavy emphasis on America as a place of freedom and opportunity – an image functional to the propaganda of the Western bloc in a critical phase of the Cold War.34 Shahn would exhibit at the Del Corso’s gallery in 1956, after a successful solo exhibition at La Tartaruga in 1955.

Two American artists exhibited at L’Obelisco during their residencies at the American Academy of Rome: the painter and muralist George Biddle, in 1952; and the surrealist painter Eugene Berman, in 1959, following his earlier exhibitions at L’Obelisco in 1949, during his Guggenheim Fellowship in Italy, and in 1952. It should also be mentioned that among the U.S. sculptors who exhibited at L’Obelisco were as Harvey Fite, in 1950, and Joseph Greenberg, the following year. Additionally, Stanley B. Kearl, in Italy in 1949–50 on a Fulbright Grant, was given a solo exhibition in 1951 by the del Corsos, while in 1959 they spotlighted Beverly Pepper, who would settle in Italy with her husband, journalist and author Curtis Bill Pepper.

The similarity of choices made by L’Obelisco and American institutional politics is undeniable, although to date it has not been possible to draw further conclusions from recorded observations. A dominant feature of the unconventional and international openness of the era is the ease with which personal relationships and suggestions from the artists themselves translated into exhibitions, often of short duration, which alternated at a dazzling rhythm in the small gallery at Via Sistina 146. The idea of exhibiting Kay Sage in 1953 was hatched a month before her show opened in March – during the exhibition of her husband, Yves Tanguy. Hedda Sterne was recommended directly by Steinberg for her show on April 1953,35 while Vera Stravinsky’s exhibitions, in 1955 and 1958,36 were arguably prompted by the frequent participation of Igor Stravinsky in music festivals and receptions organized by Roberts at the American Academy.37 Berman, friend and collaborator of the Russian composer and the del Corso couple, wrote the introductory text to Vera Stravinsky’s first exhibition.

As of the mid-1940s and far into the following decade, the del Corsos’ exhibition policy was marked by its plurality and eccentricity of proposals, while maintaining a certain continuity in displaying Fantastic art of metaphysical and surrealist derivation.

Beginning the Exchange between Rome and New York: the Young Italian Fantasts and the American Surrealists.

Many of the Americans who arrived in the Italian capital after its liberation frequented the first gallery of the del Corso couple, La Margherita, including the director William Wyler, who filmed the aforementioned Roman Holiday in 1953, as well as the award-winning Ben-Hur in 1959. Stimulated by such clientele, Gaspero del Corso decided to conduct his overseas business through a trusted collaborator.38 Among those in del Corso’s purview was Peter Lindamood, who, as previously noted, was involved in an intelligence operation in Rome. As Giulia Tulino has documented, Lindamood’s articles on Italian Fantastic art in Town and Country, Harper’s Bazaar, and View facilitated the export from Rome to New York of works by Italian artists such as Leonor Fini, Fabrizio Clerici, and Giuseppe Viviani.39 In his writings, Lindamood located in the works of Giorgio de Chirico and his brother, the musician, writer, and painter Alberto Savinio, the origins of a lasting visionary art that mixed together archeological quotations and surrealist glances, descriptive realism and oneiric sceneries. In so doing he identified a certain continuity between metaphysical art and the various figurative stances of younger Italian artists, such as the citationist surrealism of Clerici, the visionary etchings of Viviani, the Fantastic art of Stanislao Lepri, the “naive” narratives of Gianfilippo Usellini, inspired to Fifteenth-Century Italian Art, and the expressionist satire of Tono Zancanaro.

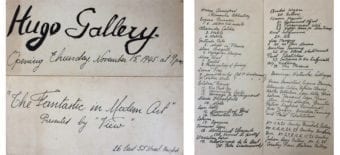

The commercial surrealist connection recognized by Lindamood was supported by a fundamental figure, Alexander Iolas, a resourceful Greek-born dancer who moved from Paris to New York, where, in 1944, he began an extraordinarily successful career as an art dealer. Secretly advised by Lindamood to contact the del Corsos, he wrote to Gaspero introducing himself as “a friend of Leonor” and requesting to exhibit works by some La Margherita artists (Fini, Stanislao Lepri, Filippo de Pisis, and others) in the opening exhibition, in 1945, of the Hugo Gallery in New York, where he was director. Titled The Fantastic in Modern Art presented by “View,” the exhibition’s invitation documents that Fini and Lepri did take part, as did Clerici (figures 5a–5b); the works of de Pisis and Vespignani (a discovery of Gaspero del Corso) were featured by Iolas in two solo exhibitions.40 This is how the otherwise inexplicable section of MoMA’s Twentieth-Century Italian Art exhibition called “The Fantasts” originated: Clerici, Lepri, and Viviani – introduced in the catalogue as disciples of Fini – all came from La Margherita, while Salvatore Fiume joined them through other channels.41

In subsequent years, “Iolas’s artists” traveled to Italy from America. Among the artists included in Iolas’s 1945 inaugural exhibition: Tanguy held his first Italian exhibition at L’Obelisco in 1953; Tchelichew exhibited there twice, in 1950 and 1955; Berman was introduced by Corrado Cagli in the catalogue of his first Italian solo exhibition at L’Obelisco, in 1949, and also exhibited there in 1959 and 1961; and in 1954 it was the turn of Eugene’s brother, Leonid. The visitors to Rome in the aftermath of the war and the fortuitous exchange with Iolas thus favored the opening of a channel for Fantastic art’s import and export – “Americans” (perhaps naturalized) in exchange for young Italians.

Berman, Tanguy, and Tchelichew had all been in Paris during to the war, as was Iolas, who thus came into contact with many exiled artists, including Fini. In New York in 1942, they participated together in the exhibition Artists in Exile, at the Pierre Matisse Gallery. Whereas Tanguy obtained American citizenship in 1948 and would remain in Connecticut with his wife, Berman and Tchelichew were particularly fascinated by the Roman context; Berman, looking for change after his wife’s suicide, settled in the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj and remained there until his death, in 1972, while Tchelichew spent the last years of his life in Grottaferrata, a few miles from the capital, with his partner Charles Henri Ford. Among other things, Ford was co-editor of the surrealism-focused magazine View, which in 1945 featured the Fantastic Art exhibition at Hugo Gallery.

For Tchelichew and Berman, Rome was a particularly favorable location from a professional point of view, for it brought them into contact with new collectors, and notably, members of the aristocratic clientele of L’Obelisco. This was also the case for Carlyle Brown, an admirer of Tchelichew, who was immortalized by the camera of Herbert List in 1951 in Ischia; in those years he frequented several artists from L’Obelisco, such as Clerici, Leonardo Cremonini,42 and Tchelichew, who loved spending time on this island. Among the gallery’s aristocratic Roman clientele, Brown found patrons in Enrico D’Assia, Prince Alessandro Ruspoli, and Countess Anna Laetitia Pecci Blunt (figures 6a–6b).43

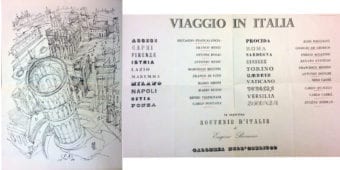

Berman deserves special attention for having developed his artistic vision through his career as a set and costume designer for Italian theater and opera.44 He adapted his metaphysical and Dalí-influenced imagery in paintings of the Mediterranean landscape and Rome’s archaeological ruins. The mixture was highly attractive to American visitors to the Eternal City. Indeed, their point of view is well depicted in the best-seller Rome and a Villa, by the American writer Eleanor Clarke; the 1952 book is dedicated to Isabel and Laurance Roberts and illustrated by Berman. The scenery of “Hollywood on the Tiber,” where fake ruins get thrown up around real ones, is described by Clarke as dreamlike, “both real and not real,” “a place secret, sensuous, oblique, a poem and to be known as a poem; a vast untidiness peopled with characters and symbols so profound they join the imagery of your own dreams, whose grandeur also is of dreams, never of statements or avenues.”45 Quoting Füssli and Piranesi, Berman adds nostalgic flavor, by which inner solitude in the present encounters the temporal vertigo disclosed by Roman antiquities (figure 7). Berman also illustrated Viaggio in Italia (1951) by Raffaele Carrieri, a writer and critic sensitive to metaphysical and Fantastic art who, three years later, would curate a Venice Biennale exhibition dedicated to surrealism.46 A group exhibition titled Viaggio in Italia, held at L’Obelisco in January 1952, was accompanied by a brochure that included an illustration by Berman, of Souvenir d’Italie (Souvenir of Italy; figures 8a–8b). In Berman’s rendering, the Grand Tour of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe acquired a glamorous and touristic hue – extremely appealing to the international clientele that frequented the gallery during the 1950s.

Like Berman, Roberto Matta started to frequent L’Obelisco following a period of mourning: his friend Arshile Gorky had committed suicide, and Matta was widely held responsible because of his romantic affair with Gorky’s wife. The event isolated him in the New York art community, as well as bringing André Breton’s (temporary) moral condemnation. After a quick return to Chile, following the advice of Iolas he headed to Rome, where he was welcomed by American acquaintances including Carone, Gendel, the secret agent Peter Tompkins, and Cagli.47 Introduced by the latter to L’Obelisco, his exhibition Fosforesciamo opened there on January 12, 1950 (figure 9). However, relations with the gallery owners were abruptly interrupted – as recounted by a bewildered del Corso in his agenda – by unspecified unacceptable behavior on the part of Matta.48 Matta would settle in Italy, and after only two months he had already formed new contacts with the galleries La Salita and Schneider in Rome, and Il Naviglio in Milan and Il Cavallino in Venice, both run by Carlo Cardazzo. His art impressed artists such as Afro, Burri, Marca-Relli, and Giuseppe Capogrossi.49 His painting, which in New York had reached its peak as abstract and multidimensional landscaping, in Italy acquired greater narrative and iconographic concreteness.

Three famous cases: Robert Rauschenberg, Alexander Calder, and Arshile Gorky

While the programmatic line of L’Obelisco can be identified according to a general post-metaphysical and surrealist trend, other cases can also be related by circumstance. In March 1953, L’Obelisco held the first exhibition in Italy, and Europe, of a very young Rauschenberg, Scatole e Feticci personali (Personal Boxes and Fetishes; figures 10a–10b) – a display of developments from his study trip to Morocco and Italy with his friend Cy Twombly. Rauschenberg exhibited some boxes with found objects, reminiscent of the work of Joseph Cornell, while his “personal fetishes” were assemblages of “bones, hair, faded clothes, feathers [and] ropes” alongside “mirrors, insects, pearls, and shells.”50 A probable re-elaboration of apotropaic objects and rituals he had learned about in North Africa, the “fetishes” found an environmental outward dimension at Villa Borghese, a few meters from L’Obelisco, as documented in Rauschenberg’s photographs. (At the time he considered himself primarily a photographer.)

What del Corso in his agenda defines as “random objects, but indicative of the research of many young people today,”51 were put on sale at a very low price: the exhibition was treated almost as a collective game, and, to the amazement of the gallery’s owners, some objects sold immediately. Many of the unsold objects Rauschenberg threw into the River Arno after an exhibition in Florence in March 1953, in a “Futurist” gesture suggested to him by a sardonic reviewer, the art historian Carlo Volpe.52

Thanks to L’Obelisco, Rauschenberg visited Burri, who had already exhibited at the gallery in 1952 and would do so again in 1954 and 1957. The meeting was described by the American as a cordial trade of works, while the Italian recalled it with ostentatious indifference.53 A second phase of this relationship would play out in New York, at the Stable Gallery under Carone’s direction. Rauschenberg and Twombly’s two-person exhibition in September 1953 was followed by Burri’s solo exhibition two months later, which was carefully photographed by Rauschenberg.

A lot has been written about the Burri-Rauschenberg meeting and the impact of Burri’s Sacks, begun in the 1950s, on Rauschenberg’s Combines, begun in 1954. Some Italian critics, such as Maurizio Calvesi and Germano Celant, have spoken of the elder artist’s decisive influence on the American, and comments from Burri recorded in a 1995 retrospective interview reflect this view.54 Recently, the tendency has been to talk more about an exchange between the artists, whose lines of research were markedly individual, and would remain substantially different.55 No doubt a contribution to the introduction of extra-pictorial materials in the Combines was accelerated by contact with the Roman Informel art milieu: another piece of this mosaic can be identified in Salvatore Meo, an Italian-American who met Twombly and Rauschenberg in Rome in 1952. Close to Burri and Colla, he was making poetic assemblages with found objects that – he claims – exerted a decisive influence on both Burri and Rauschenberg.”56

Generally, the Rauschenberg exhibition is attributed to the mediation of Burri. A small novelty that emerges from the documents of L’Obelisco is that, according to Irene Brin, the person behind the exhibition was Guidarino Guidi, friend of the del Corso couple and a future casting director at De Laurentiis, who spoke English fluently and who in those years acted as a press agent and valued assistant to film producers. Thus, Gaspero del Corso’s incredible insight was defined by particular flexibility and curiosity in grasping external suggestions from outside of the art system. This unconventional openness led him to oversee artistic debuts of varied kinds, from the young American photographer and advertising producer Will Golovin, who exhibited at L’Obelisco in 1951,57 to the American model Ivy Nicholson, whose forays into painting were displayed at L’Obelisco in 1956 (and eventually led her to Andy Warhol’s Factory).

Two other developments should be mentioned. The first is the solo exhibition of Alexander Calder held in March of 1956 (figure 11). In 1952 he had been awarded the Grand Prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale, and two years later he created a mobile for the Milan Triennale. A decisive meeting at his L’Obelisco exhibition favorably marked the career of the American sculptor in Italy, with Giovanni Carandente, an art historian and good friend of Gaspero del Corso, inviting Calder, in 1962, to create the famous Teodelapio in the square of the Spoleto railway station, as part of the prestigious Festival dei Due Mondi, founded in 1958 by the composer Gian Carlo Menotti to foster relations between Europe and the U.S. “Caro Carandente, instead of a mobile I am making you a stabile, which will stand in the ground, + arch the roadway,” wrote Calder to Carandente on April 20, 1962.58 Teodelapio was Calder’s first monumental stabile, and, according to Carandente, “the only truly modern large and important sculpture”59 erected in an Italian square. As was true for Berman and Matta in Rome, the exchange was reciprocal and the encounter productive, for Calder and for Italy.

The last episode to mention here is the first European retrospective of Gorky’s work. As mentioned above, visits to the capital by young Abstract Expressionists did not revolve only around L’Obelisco but also Plinio De Martiis’s gallery La Tartaruga, inaugurated in 1954. In the summer of 1957, an issue of Arti visive was dedicated to Gorky by Drudi and Scialoja, who had just returned from America; in New York they had seen Gorky’s solo exhibition at the Catherine Viviano Gallery.60 The Arti visive issue was to be the “first tribute to the artist in Europe,” Drudi wrote.61 However, L’Obelisco had anticipated this celebration on February 4 of the same year; their presentation of the artist has since been described as “the last of the surrealists and the first of the Abstract Expressionists.”62 According to Irene Brin’s account, the exhibition involved a brilliant solution to a difficulty caused by the political context. The fear of another war, caused by events in Hungary, had stranded the artist’s works at an American gallery, but the couple managed to replace them by contacting Gorky’s widow, Mougouch Fielding, who was then residing in Tuscany. Fielding lent L’Obelisco twenty-nine drawings and nine oil paintings63 for the exhibition, which was acclaimed by critics and the public and traveled from Rome to Bologna.64 A strong network of contacts had allowed the couple to once again break new ground.

The catalogue exhibition was introduced by Afro with a sincere personal tribute.65 According to Adachiara Zevi and Barbara Drudi, it was Afro and Scialoja who organized the exhibition, and they were rewarded by Fielding with two works by Gorky.66 After having held his “first abstract exhibition” at L’Obelisco in 1948, Afro had become detached from the gallery for commercial reasons: the high-price policy of his New York dealer Viviano was disturbed by the less select clientele and low-cost sales of the del Corsos. From the perspective of the market, the couple were carrying out a strategic double policy: the bold experimentation and risk taking of radical artists ahead of their time was supported by the constant profitable trade of poor-quality works by minor authors, such as Nino Caffè or Andrea Spadini, who were much admired by tourists, entrepreneurs, and newly rich Americans.67

A Symbolic Epilogue: Farewell to the Roberts, 1959

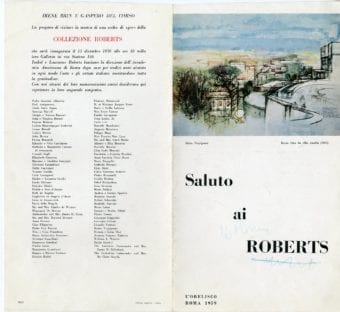

Afro wrote a text as well for the exhibition Saluto ai Roberts (Farewell to the Roberts; figure 12), which concluded the decade of exhibitions held at L’Obelisco. With it, the gallery owners wished to thank the director of the American Academy for his affectionate and constant support of Italian art over the course of his long tenure in Rome. Before an audience of diplomats, intellectuals, and first-rate artists, Gaspero del Corso and Irene Brin celebrated their friends. Surprisingly – though perhaps not really – the works on display from the Roberts’ art collection were almost all by artists from the circle of L’Obelisco.68 The del Corsos were thus also celebrating their own artistic and political position and successful commercial enterprise. The episode once again confirmed the strength of their network of contacts – which indeed involved a certain unscrupulousness, and a position of strategic proximity to the major American cultural institution in Rome – and symbolically marked the end of an era of exciting, mutual openness between Italy and the U.S., achieved independently and off the beaten track.

Bibliography

“Americans in Italy: U.S. Artists Repeat Migration of 1800s with Fresh Results.” Life, September 15, 1952.

Appella, Peppino. “Artisti, scrittori, critici, architetti e gallerie a Roma negli anni Cinquanta.” In D’Amico, Roma 1950–1959, 109–35.

Bair, Deirdre. Saul Steinberg: A Biography. New York: Doubleday, 2012.

Balzarotti, Rodolfo and Barbieri, Giuseppe. In William Congdon: An American Artist in Italy. Vicenza: The William Congdon Foundation and Terraferma, 2001.

Barr, Alfred H., Jr., and Soby, James Thrall. Twentieth-Century Italian Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “Export/Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969.” PhD diss., Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2016.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “Mr. In-Between.” In Salvatore Scarpitta 1956–1964, 8–12. New York: Luxembourg & Dayan, 2016.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “Viviano, Brin e la conquista di Hollywood.” In New York New York, edited by Francesco Tedeschi with Federica Boragina and Francesca Pola, 117–26. Milan: Electa, 2017.

Belli, Gabriella, ed. Afro: The American Years. Rovereto: Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto (MART), 2012.

Belli, Gabriella, ed. Arshile Gorky: 1904–1948. Venice: Ca’ Pesaro, Galleria Internazionale di Arte Moderna, 2019.

Berman, Eugene. Imaginary Promenades in Italy. New York: Pantheon, 1956.

Bernardi, Ilaria. La Tartaruga. Storia di una galleria. Milan: Postmedia, 2018.

Brin, Irene. “Crónica de Roma.” Goya, April–May 1957, 316–17.

Brin, Irene. L’Italia esplode. Diario dell’anno 1952. Edited by Claudia Palma, with texts by Claudia Palma, Vittoria Caterina Caratozzolo, and Ilaria Schiaffini. Rome: Viella, 2014.

Brody, Martin. “Class of ’54: Friendship and Ideology at the American Academy in Rome.” In Music and Musical Composition at the American Academy in Rome, edited by Martin Brody, 222–54. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2014.

Camerlingo, Rita, and Maria D’Alesio. “La Galleria L’Obelisco (1946–1981), Regesto delle mostre.” In Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, edited by Caratozzolo et al., 270–307.

Carandente, Giovanni. “Calder e l’Italia.” In Calder. Scultore dell’aria, edited by Alexander S. C. Rower. Rome: Palazzo delle Esposizioni, 2009.

Caratozzolo, Vittoria Caterina. Irene Brin: Italian Style in Fashion. Milan: Marsilio; Garsington: Windsor [distributor], 2006.

Caratozzolo, Vittoria Caterina, Ilaria Schiaffini, and Claudio Zambianchi, eds. Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco. Rome: Drago, 2018.

Caruso, Rossella. “Robert Rauschenberg alla Galleria L’Obelisco. Scatole e feticci personali.” In Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, edited by Caratozzolo et al., 205–16.

Clark, Eleanor. Rome and a Villa. New York: Doubleday, 1952.

Colombo, Davide. “Arti Visive e dintorni.” In Emilio Villa. Poeta e scrittore, edited by Claudio Parmiggiani, 285–97. Milan: Mazzotta, 2008.

Colombo, Davide. “Arti Visive, una rivista ‘tra’: astrattismi, interdisciplinarietà, internazionalismo.” PhD. diss., Milan: Università degli Studi di Milano, 2010.

Colombo, Davide. “Arti Visive e Ann Salzman: un ponte tra Italia e America sulla scena artistica degli anni Cinquanta.” L’Uomo nero 8, nos. 7–8 (December 2011): 86–107.

Colombo, Davide. “Salvatore Scarpitta: On Both Sides of the Atlantic.” In Salvatore Scarpitta 1956–1964, 12–19. New York: Luxembourg & Dayan, 2016.

Colombo, Davide. “Un caso singolare: il mercato americano di Leonardo Cremonini durante gli anni ’50.” In Ricerche di S/Confine 8, n. 1 (2017): 21–45.

Colombo, Davide. “1949: Twentieth-Century Italian Art al MoMA di New York.” In Afro, edited by Philip Rylands, 59–67. Paris: Tornabuoni Art; Florence: Forma Edizioni and Tornabuoni Art, 2018.

Costanzo, Denise R. “‘A Truly Liberal Orientation:’ Laurance Roberts, Modern Architecture, and the Postwar American Academy in Rome.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 2 (June 2015): 223–47.

Crespi Morbio, Vittoria. Eugene Berman alla Scala. Milan: Amici della Scala; Parma: Grafiche Step Editrice, 2017.

Cullinan, Nicolas. “Double Exposure: Robert Rauschenberg’s and Cy Twombly’s Roman Holiday.” Burlington Magazine 150, no. 1264 (July 2008): 460–70.

D’Amico, Fabrizio. Arte a Roma dal primo al secondo dopoguerra. Rome: Edizioni della Cometa, 1995.

D’Amico, Fabrizio, ed. Roma 1950–1959. Il rinnovamento della pittura in Italia. Turin: Civiche Gallerie d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, 1995.

Dabakis, Melissa. Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014.

Di Stefano, Chiara. “La partecipazione di Ben Shahn alla Biennale di Venezia del 1954.” In Crocevia Biennale, edited by Francesca Castellani and Eleonora Charans, 181–90. Milan: Scalpendi, 2017.

Diacono, Mario. “Burri e/o l’America: il Ground Zero della pittura.” In Burri. Lo spazio di materia tra Europa e USA, edited by Bruno Corà. Città di Castello: Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, 2016.

Dossin, Catherine. The Rise and Fall of American Art, 1940s–1980s: A Geopolitics of Western Art Worlds. Farnham Surrey, U.K., and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2015.

Drudi, Barbara. “A Step on the Stairway to Heaven: Afro alla Galleria L’Obelisco, 1948–1959.” In Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, edited by Caratozzolo et al., 171–82.

Drudi, Barbara. Afro da Roma a New York. Pistoia: Gli Ori, 2008.

Drudi, Barbara. Milton Gendel. Uno sguardo lungo un secolo. Gli anni tra New York e Roma 1940–1962. Macerata: Quodlibet, 2017.

Drudi, Barbara, and Giacomo Marcucci. Arti Visive 1952–1958. Pistoia: Gli Ori, 2011.

Drudi, Gabriella. “Prima e dopo.” In Roma 1950–1959. Il rinnovamento della pittura in Italia, edited by Fabrizio D’Amico, 25–32. Turin: Civiche Gallerie d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, 1995.

Duncan, Michael, ed. High Drama: Eugene Berman and the Legacy of the Melancholic Sublime. New York and Manchester: Hudson Hills Press, 2005.

Fontanella, Megan. “Begun Behind Barbed Wire: Alberto Burri’s Early Career in America.” In Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting, edited by Emily Braun. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2015.

G.B.V. “Un secolo in Quattro passi.” Il Momento, February 9, 1950.

Harris, Lindsay. “Pictures in the Mind: Photography and Matera.” In Matera Imagined: Photography and a Southern Italian Town. Rome: American Academy; Matera: Palazzo Lanfranchi, 2017.

Lader, Melvin P. “Arshile Gorky: un artista moderno nella tradizione accademica.” In Arshile Gorky. Opere su carta. Rome: Carte Segrete, 1992.

LaGumina, Salvatore J. The Office of Strategic Services and Italian Americans: The Untold History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Miller, Peter Benson. “Resident/Alien: American Artists in Postwar Rome.” In Roma e gli artisti stranieri. Integrazione, reti identità (XVI–XX sec.), edited by Ariane Varela Braga and Thomas Leo-True, 221–38. Rome: Artemide, 2018.

Miller, Peter Benson, ed. Go Figure! New Perspectives on Guston. New York: New York Review of Books, 2014.

Pohl, Frances K. Ben Shahn – New Deal Artist in a Cold War Climate 1947–1954. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989.

Drudi, Barbara. “Come Afro conquistò l’America.” In Afro, edited by Philip Rylands, 73–123. Paris: Tornabuoni Art; Florence: Forma Edizioni and Tornabuoni Art, 2018.

Sachs, Sid. Salvatore Meo: Assemblages 1948–1978. New York: Pavel Zoubok Gallery; Philadelphia: Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, University of the Arts, 2008.

Salaris Claudia, ed. Sebastian Matta: un surrealista a Roma. Milan: Giunti; Rome: Fondazione Echaurren Salaris, 2012.

Salvatore Meo. Mostra antologica: assemblages e disegni (1945–1971). Rome: Galleria Ciak, 1971.

Schiaffini, Ilaria. “Between Fashion, Art and Photography: Irene Brin and the Early Activities of the Galleria L’Obelisco.” In Fashion Through History. Costumes, Symbols, Communication, edited by Giovanna Motta and Antonello Biagini, vol. 2, 591–603. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017.

Schiaffini, Ilaria. “L’arte sullo sfondo de L’Italia esplode: Irene Brin e i primi anni della galleria L’Obelisco.” In Irene Brin, L’Italia esplode, 159–89.

Schiaffini, Ilaria. “La fotografia alla Galleria L’Obelisco: documentazione, esposizione, comunicazione.” In Archivi fotografici e arte contemporanea in Italia. Indagare, interpretare, inventare, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Antonello Frongia, 81–100. Milan: Scalpendi, 2019.

Schiaffini, Ilaria. “La Galleria L’Obelisco e il mercato americano.” In Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, edited by Caratozzolo et al., 125–44.

Schwabacher, Ethel. Arshile Gorky. New York: The Macmillan Company for the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1957.

Scialoja, Toti. “Per Gorky,” dated “New York, October 1956.” Arti Visive V, nos. 6–7 (1957).

Smith, Joel. Saul Steinberg: Illuminations. Poughkeepsie, NY: Vassar College; New York: The Morgan Library, 2006.

Smith, Richard Harris. OSS: The Secret History of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

Stonor Saunders, Frances. Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War. London: Granta Books, 1999.

Tedeschini Lalli, Mario. “Descent from Paradise: Saul Steinberg’s Italian Years (1933–1941).” Quest: Issues in Contemporary Jewish History, no. 2 (October 2011): 312–84.

Tobia, Simona. Advertising America: The United States Information Service in Italy (1945–1956). Milan: LED Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto, 2008.

Tompkins, Peter. A Spy in Rome. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1962.

Tulino, Giulia. “Dalla Margherita all’Obelisco: arte fantastica italiana tra Roma e New York negli anni ’40.” In Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, edited by Caratozzolo et al., 109–24.

Tulino, Giulia. “Alberto Savinio, critic and artist: a New Reading of Fantastic and Post-Metaphysical Art in Relation to Surrealism Between Rome and New York.” Italian Modern Art, no. 2 (July 2019), available at this link (last accessed January 20, 2020).

Volpe, Carlo. “Alla Galleria d’Arte contemporanea.” Il Nuovo Corriere, March 25, 1953, 3.

Waller, Douglas. Wild Bill Donovan: The Spymaster Who Created the OSS and Modern American Espionage. New York: Free Press, 2012.

Zevi, Adachiara. Peripezie del dopoguerra nell’arte italiana. Turin: Einaudi, 2006.

Zorzi, Stefano. Parola di Burri. I pensieri di una vita. Turin: Edizioni Allemandi, 1995.

Archival sources

Carone, Nicholas, interviewed by Paul Cummings, May 11–17, 1968. Oral Histories, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. available at this link (last accessed January 20, 2020).

del Corso, Gaspero. Agenda, 1953. Fondo Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome.

How to cite

Ilaria Schiaffini, “It’s a Roman Holiday for Artists: The American Artists of L’Obelisco After World War II,” in Raffaele Bedarida, Silvia Bignami, and Davide Colombo (eds.), Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 3 (January 2020), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/its-a-roman-holiday-for-artists-the-american-artists-of-lobelisco-after-world-war-ii/, accessed [insert date].

- See, in particular, Irene Brin, L’Italia esplode. Diario dell’anno 1952, ed. Claudia Palma, with texts by Claudia Palma, Vittoria Caterina Caratozzolo, and Ilaria Schiaffini (Rome: Viella, 2014); and Vittoria Caterina Caratozzolo, Ilaria Schiaffini, and Claudio Zambianchi, eds., Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco (Rome: Drago, 2018). I wish to thank Claudio Zambianchi for his precious suggestions on this text.

- On Thrall and Soby’s trip to Italy, see Silvia Bignami and Davide Colombo’s essay, “Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and James Thrall Soby’s Grand Tour of Italy,” in this journal issue. Vespignani was the first young Italian talent discovered by L’Obelisco. The two drawings reproduced in the catalogue of Twentieth-Century Italian Art were purchased by MoMA from Alexander Iolas, who had received them from the owner of L’Obelisco, Gaspero del Corso. During their Roman trip in the spring of 1948, Barr and Soby visited Afro’s first abstract exhibition at L’Obelisco, and the gallery lent two of Afro’s works of 1948, Lis Fuarpis and Trophy, to the MoMA exhibition. See Ilaria Schiaffini, “La Galleria L’Obelisco e il mercato americano,” in Caratozzolo et al., Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la galleria L’Obelisco, 127–30.

- “Americans in Italy: U.S. Artists Repeat Migration of 1800s with Fresh Results,” Life, September 15, 1952, 88.

- On the presence of U.S. artists in Rome in the nineteenth century, see Melissa Dabakis, Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014).

- Catherine Dossin, The Rise and Fall of American Art, 1940s–1980s: A Geopolitics of Western Art Worlds (Farnham Surrey, U.K. and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2015), 68.

- Another notable Hollywood film in this vein is Three Coins in the Fountain (1954).

- See Peter Benson Miller, ed., Go Figure! New Perspectives on Guston (New York: New York Review of Books, 2014).

- Of the Americans in Rome in that period, mention should also be made of Mark Rothko, Clement Greenberg, and Helen Frankenthaler. See Barbara Drudi, Afro da Roma a New York (Pistoia: Gli Ori, 2008); Gabriella Belli, ed., Afro. The American Years (Rovereto: Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto [MART], 2012); and Barbara Drudi, “Come Afro conquistò l’America,” in Afro, ed. Philip Rylands (Paris, Tornabuoni Art; Florence: Forma Edizioni and Tornabuoni Art, 2018), 73–123.

- See Raffaele Bedarida, “Export/Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969” (PhD diss., Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2016).

- Gabriella Drudi, “Prima e dopo,” in Roma 1950–1959. Il rinnovamento della pittura in Italia, ed. Fabrizio D’Amico (Turin: Civiche Gallerie d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, 1995), 25–32. See also Davide Colombo, “Arti Visive e dintorni,” in Emilio Villa. Poeta e scrittore, ed. Claudio Parmiggiani (Milan: Mazzotta, 2008), 285–97; Davide Colombo, “Arti Visive, una rivista ‘tra’: astrattismi, interdisciplinarietà, internazionalismo” (PhD diss., Milan: Università degli Studi di Milano, 2010); Davide Colombo, “Arti Visive e Ann Salzman: un ponte tra Italia e America sulla scena artistica degli anni Cinquanta,” in L’Uomo nero 8, nos. 7–8 (December 2011): 86–107; and Barbara Drudi and Giacomo Marcucci, Arti Visive 1952–1958 (Pistoia: Gli Ori, 2011).

- See Barbara Drudi, Milton Gendel. Uno sguardo lungo un secolo. Gli anni tra New York e Roma 1940–1962 (Macerata: Quodlibet, 2017).

- Peter Benson Miller, “Resident/Alien: American Artists in Postwar Rome,” in Roma e gli artisti stranieri. Integrazione, reti identità (XVI–XX sec.), ed. Ariane Varela Braga and Thomas Leo-True (Rome: Artemide, 2018), 228–29.

- See Nicholas Carone interviewed by Paul Cummings, May 11–17, 1968, Oral Histories, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, available at this link (last accessed October 29, 2019); and Megan Fontanella, “Begun Behind Barbed Wire: Alberto Burri’s Early Career in America,” in Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting, ed. Emily Braun (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2015), 95.

- “I knew Alberto Burri before he really became a painter, I was the American that introduced him to American art. I used to give him my magazines, Tiger’s Eye and ARTnews.” Carone interviewed by Cummings, Archives of American Art. The first Burri exhibition in the U.S. took place at the beginning of 1953 at the Allan Frumkin Gallery in Chicago.

- See Ilaria Bernardi, La Tartaruga. Storia di una galleria (Milan: Postmedia, 2018), 27–28. Scarpitta, who moved from California to Rome in the 1930s, obtained a grant from the American Academy in Rome between 1946–49. At La Tartaruga he exhibited his famous bende in 1958, before returning to the U.S. Marca-Relli was among the artists exhibited at the Stable Gallery in New York; after his first shows in Rome at the Il Cortile gallery at the end of the 1940s, he returned to the capital in 1956 and held a solo exhibition at La Tartaruga the following year. On Scarpitta, see Raffaele Bedarida, “Mr. In-Between,” in Salvatore Scarpitta 1956–1964 (New York: Luxembourg & Dayan, 2016), 8–12; and Davide Colombo, “Salvatore Scarpitta: on both sides of the Atlantic,” in Salvatore Scarpitta 1956–1964 (New York: Luxembourg & Dayan, 2016), 12–19.

- See Peppino Appella, “Artisti, scrittori, critici, architetti e gallerie a Roma negli anni Cinquanta,” in D’Amico, Roma 1950–1959, 109–35.

- See Vittoria Caterina Caratozzolo, Irene Brin: Italian Style in Fashion (Milan: Marsilio; Garsington: Windsor [distributor], 2006).

- Robert Rauschenberg’s show opened on March 3; Kay Sage’s, March 16; Hedda Sterne’s, April 14; Gertrude Schweizer’s, November 18; and William Congdon’s, November 28. See Rita Camerlingo and Maria D’Alesio, “La Galleria L’Obelisco (1946–1981). Regesto delle mostre,” in Caratozzolo et al., Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, 282–85.

- See Ilaria Schiaffini, “Between Fashion, Art and Photography: Irene Brin and the Early Activities of the Galleria L’Obelisco,” in Fashion Through History: Costumes, Symbols, Communication, ed. Giovanna Motta and Antonello Biagini, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017), 591–603; and Raffaele Bedarida, “Viviano, Brin e la conquista di Hollywood,” in New York New York, ed. Francesco Tedeschi with Federica Boragina and Francesca Pola (Milan: Electa, 2017), 117–26.

- Richard Avedon, Henri Cartier-Bresson, David Duncan Douglas, Lisette Model, and Karen Radkai are some of the names mentioned in Irene Brin, L’Italia esplode. On the photography exhibitions at L’Obelisco, see Ilaria Schiaffini, “La fotografia alla Galleria L’Obelisco: documentazione, esposizione, comunicazione,” in Archivi fotografici e arte contemporanea in Italia. Indagare, interpretare, inventare, ed. Barbara Cinelli and Antonello Frongia (Milan: Scalpendi, 2019), 81–100.

- Dossin, The Rise and Fall of American Art, 69.

- See Martin Brody, “Friendship and Ideology at the American Academy in Rome,” in Music and Musical Composition at the American Academy in Rome, ed. Martin Brody (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2014), 228. On Roberts’s direction of the Academy, see Denise R. Costanzo, “‘A Truly Liberal Orientation’: Laurance Roberts, Modern Architecture, and the Postwar American Academy in Rome,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 2 (June 2015): 223–47.

- See Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War (London: Granta Books, 1999).

- See Salvatore J. LaGumina, The Office of Strategic Services and Italian Americans: The Untold History (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); Douglas Waller, Wild Bill Donovan: The Spymaster Who Created the OSS and Modern American Espionage (New York: Free Press, 2012); and Richard Harris Smith, OSS: The Secret History of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972).

- See Simona Tobia, Advertising America: The United States Information Service in Italy (1945–1956) (Milan: LED Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto, 2008).

- See Lindsay Harris, “Pictures in the Mind: Photography and Matera,” in Matera Imagined: Photography and a Southern Italian Town (Rome: American Academy; Matera: Palazzo Lanfranchi, 2017), 81–82. On the case of a photojournalist, Marjorie Collins, whom Gendel accompanied on a reporting tour of Sicily in 1950, see Drudi, Milton Gendel, 77–78.

- Leslie Gill, email to the author, October 25, 2017.

- See Ilaria Schiaffini, “La Galleria L’Obelisco e il mercato americano,” in Caratozzolo et al., Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la galleria L’Obelisco, 138.

- Steinberg had a degree in architecture from the Milan Polytechnic, where he befriended Zavattini, Achille Campanile, and Aldo Buzzi; in the 1930s he created caricatures for Il Bertoldo and Settebello. Forced to emigrate because of racial laws, he moved to New York in 1942, and went on to serve as an officer in the U.S. Navy in China and Europe. The first publications that earned him fame internationally were All in a Line (1945) and The Art of Living (1949), translated into Italian by Mondadori in 1954. In 1950, L’Europeo acquired exclusive reproduction rights to his drawings.

- See Joel Smith, ed., Saul Steinberg: Illuminations (Poughkeepsie, NY: Vassar College; New York: The Morgan Library, 2006); and Mario Tedeschini Lalli, “Descent from Paradise: Saul Steinberg’s Italian Years (1933–1941),” Quest: Issues in Contemporary Jewish History, no. 2 (October 2011): 312–84. Much detail on this topic, though not always correctly reported according to the Saul Steinberg Foundation (see here), can be found in Deirdre Bair, Saul Steinberg: A Biography (New York: Doubleday, 2012), 97–98. Milton Gendel was deployed to China in August 1945, after having collaborated with the U.S. Army in perfecting the techniques of camouflage. See Drudi, Milton Gendel, 52.

- Bair, Saul Steinberg, 111–13 and 144.

- See the mention of Congdon’s Venetian paintings in “Americans in Italy,” a Life article (April 30, 1951) devoted to his solo exhibition. See also Rodolfo Balzarotti’s and Giuseppe Barbieri’s contributions to William Congdon: An American Artist in Italy (Vicenza: The William Congdon Foundation and Terraferma, 2001).

- See Schiaffini, “La Galleria L’Obelisco e il mercato americano,” 141. As an actress, a fashion journalist, and the wife of an editor of many high-profile American magazines – including Time, Life, and Fortune – Clare Booth Luce carried out a markedly anticommunist diplomatic activity.

- Frances K. Pohl, Ben Shahn – New Deal Artist in a Cold War Climate 1947–1954 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989). On the Italian debate, see Chiara Di Stefano, “La partecipazione di Ben Shahn alla Biennale di Venezia del 1954,” in Crocevia Biennale, ed. Francesca Castellani and Eleonora Charans (Milan: Scalpendi, 2017), 181–90.

- “Steinberg telephoned from Paris to arrange an exhibition for his wife Hedda Sterne.” Gaspero del Corso, agenda entry on March 6, 1953, available at Fondo Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome. Translation by the author.

- In 1959, Vera’s son Theodore Stravinsky exhibited at L’Obelisco.

- The important festival of contemporary music was directed and organized in 1954 at the American Academy in Rome by the former CIA agent Nabokov, who invited his long-time friend Stravinsky. See Saunders, Who Paid the Piper?, 198–99. The opposition of the cosmopolitan Western modernism of Stravinsky to Soviet realism aimed to demonstrate aesthetic pluralism as a sign of cultural freedom. See Brody, Music and Musical Composition, 239ff.

- See Schiaffini, “La Galleria L’Obelisco e il mercato americano,” 129.

- See Giulia Tulino, “Alberto Savinio, Critic and Artist: a New Reading of Fantastic and Post-Metaphysical Art in Relation to Surrealism Between Rome and New York,” Italian Modern Art, no. 2 (July 2019), available at this link (last accessed October 29, 2019); and “Dalla Margherita all’Obelisco: arte fantastica italiana tra Roma e New York negli anni ’40,” in Caratozzolo et al., Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, 109–24.

- See Schiaffini, “La Galleria L’Obelisco e il mercato americano,” 129–30.

- See Davide Colombo, “1949: Twentieth-Century Italian Art al MoMA di New York,” in Rylands, Afro, 59–67. Leonor Fini, mentioned in the introductory text of the catalogue, was not included in the exhibition. See Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and James Thrall Soby, Twentieth-Century Italian Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 31.

- See Davide Colombo, “Un caso singolare: il mercato americano di Leonardo Cremonini durante gli anni ’50,” in Ricerche di S/Confine 8, n. 1 (2017): 21–45.

- In the leaflet of Brown’s solo exhibition at L’Obelisco, these names are among those of his collectors, and the Catherine Viviano Gallery in New York is thanked as a supporter of the exhibition. See “Carlyle Brown,” Galleria L’Obelisco, November 16, 1954, Fondo Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome.

- See Michael Duncan, ed., High Drama: Eugene Berman and the Legacy of the Melancholic Sublime (New York and Manchester: Hudson Hills Press, 2005); and Vittoria Crespi Morbio, Eugene Berman alla Scala (Milan: Amici della Scala; Parma: Grafiche Step Editrice, 2017).

- Eleanor Clark, Rome and a Villa (New York: Doubleday, 1952), 23–24.

- The illustrations by Berman were later collected in Imaginary Promenades in Italy (New York: Pantheon, 1956).

- See Claudia Salaris, “Tutte le strade portano a Roma,” in Sebastian Matta: un surrealista a Roma (Milan: Giunti; Rome: Fondazione Echaurren Salaris, 2012), 134. On the spy activities of Peter Tompkins, see his autobiography, A Spy in Rome (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1962). Carone spoke of the role Iolas played in suggesting that Matta contact him in Rome. See Carone interviewed by Cummings, Archives of American Art.

- See Schiaffini, “L’arte sullo sfondo de L’Italia esplode: Irene Brin e i primi anni della galleria L’Obelisco,” in Irene Brin, L’Italia esplode, 179.

- According to Carone, Matta was welcomed by him in his studio, where he worked during his first year in Rome. He also exerted a great influence on Afro, Burri, and Capogrossi. See Carone interviewed by Cummings, Archives of American Art.

- Rossella Caruso, “Robert Rauschenberg alla Galleria L’Obelisco. Scatole e feticci personali,” in Caratozzolo et al., Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, 211. Translation by the author.

- Ibid., 210.

- Carlo Volpe, “Alla Galleria d’Arte contemporanea,” Il Nuovo Corriere, March 25, 1953, 3.

- Nicolas Cullinan, “Double Exposure: Robert Rauschenberg’s and Cy Twombly’s Roman Holiday,” Burlington Magazine 150, no. 1264 (July 2008): 467.

- Stefano Zorzi, Parola di Burri. I pensieri di una vita (Turin: Edizioni Allemandi, 1995) 33–38. On the querelle, see Germano Celant, “Roma–New York 1948–1964,” in Celant and Costantini, Roma–New York 1948–1964 (Milan: Charta, 1993), 19–23 and cited bibliography.

- See Cullinan, “Double Exposure,” 466–68; and Mario Diacono, “Burri e/o l’America: il Ground Zero della pittura,” in Burri. Lo spazio di materia tra Europa e USA, ed. Bruno Corà (Città di Castello: Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, 2016), 59–61.

- Miller, “Resident/Alien: American Artists in Postwar Rome,” 227. On the proximity of Meo to Burri and Colla in the early 1950s and on Burri’s appreciation of him, see Angelo Savelli, “(April 1951),” in Salvatore Meo. Mostra antologica: assemblages e disegni (1945–1971) (Rome: Galleria Ciak, 1971), 17; and Sid Sachs, Salvatore Meo: Assemblages 1948–1978 (New York: Pavel Zoubok Gallery; Philadelphia: Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, University of the Arts, 2008), 21–22.

- “[Golovin] is thirty-seven years old, he is a Russian-American, he is an advertising producer, and his dream is to become a painter. For now he is content with photographing every corner of the world he visits on his long journeys.” G.B.V., “Un secolo in Quattro passi,” Il Momento, February 9, 1950. Translation by the author.

- Biblioteca Giovanni Carandente, Spoleto.

- Giovanni Carandente, Calder e l’Italia, in Calder. Scultore dell’aria, ed. Alexander S. C. Rower (Rome: Palazzo delle Esposizioni, 2009), 29.

- The tribute in 1957 in issues 6 and 7 of Arti Visive included anticipations of the still-unpublished monograph with texts by Ethel Schwabacher for the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. See Arshile Gorky (New York: The Macmillan Company for the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1957). See also the tribute by Toti Scialoja in these issues of Arti Visive, “Per Gorky,” written in October 1956. On Gorky’s impression of Scialoja when he was in New York for the show at the Catherine Viviano and for Gabriella Drudi’s account, see Celant and Costantini, Roma–New York 1948–1964, 119–22.

- Drudi, “Prima e dopo,” 32. See also Gabriella Belli, ed., Arshile Gorky: 1904–1948 (Venice: Ca’ Pesaro, Galleria Internazionale di Arte Moderna, 2019).

- Melvin P. Lader, “Arshile Gorky: un artista moderno nella tradizione accademica,” in Arshile Gorky. Opere su carta (Rome: Carte Segrete, 1992), 15. Fabrizio D’Amico recalls how Gorky was the least American of the Americans, the one most tied to European culture because of his Armenian origins and the relations he had established with the entourage of Pierre Matisse – that is, the Parisian surrealist milieu that had roots in New York. See Arte a Roma dal primo al secondo dopoguerra (Rome: Edizioni della Cometa, 1995), 129.

- Irene Brin, “Crónica de Roma,” Goya, April–May 1957, 316–17.

- The exhibition had a second venue in La Loggia gallery in Bologna. In her article, Irene Brin mentions also the Galleria Montenapoleone in Milan, but this is not confirmed by the Arshile Gorky Foundation. See Irene Brin, “Crónica de Roma,” 317.

- Barbara Drudi contests Afro’s authorship and hypothesizes a contribution by Toti Scialoia. See Drudi, Afro da Roma a New York, 36–39.

- See Adachiara Zevi, Peripezie del dopoguerra nell’arte italiana (Turin: Einaudi, 2006), 112; and Barbara Drudi, “A Step on the Stairway to Heaven. Afro alla Galleria L’Obelisco 1948–1959,” in Caratozzolo et al., Irene Brin, Gaspero del Corso e la Galleria L’Obelisco, 181.

- Gabriella Drudi recalls how in that period “there was never any money, but there was always the tourist on his way to L’Obelisco gallery who instead of buying Nino Caffè became enamored with Burri.” Drudi, “Prima e dopo,” 28. On the relationship with Viviano, see Drudi, “A Step on the Stairway to Heaven,” 179–80.

- See Schiaffini, “La Galleria L’Obelisco e il mercato americano,” 138–41.