Neocubism and Italian Painting Circa 1949: An Avant-Garde That Maybe Wasn’t

Adrian R. Duran Adrian R. Duran Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of-exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/

This essay considers the category and style of “Neocubism” within the Italian avant-garde of the 1930s and 40s. A term applied to artists such as the Corrente group and Il Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, “Neocubism” became loaded with political and aesthetic connotations in the last years of Fascism and the first of the postwar period. These young Italian artists were deeply influenced by the work of the Cubists, but especially that of Pablo Picasso. His 1937 Guernica became an ideological touchstone for a new generation that had endured Fascism and joined in the partisan fight against Nazi occupation. This essay seeks to disentangle this knotted legacy of Cubism and point to the rapidly changing stakes of the surrounding discourse, as Italy transitioned from Fascist state to postwar Republic to Cold War frontier. Adding nuance and diversity to a term so often applied monolithically will allow for a truer sense of Italian Neocubism when and if it was manifested throughout this period.

To be found amidst a panorama of earlier, often better-known examples of Italian modernism on display at the Museum of Modern Art’s 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art was a new generation of painters and sculptors, thrust into the spotlight of a discourse within which they had not yet found their place. Groups such as the Futurists and the Scuola Metafisica and individual artists, for instance Amedeo Modigliani, had already been integrated into the master narratives of early twentieth-century modernism. For the newly emergent generation, which MoMA named “The Younger Abstractionists; the Fronte nuovo delle arti,” the narrative was still being written. Indeed, their young careers had already faced massive uncertainty – Fascism, World War II, the Resistance, and postwar recovery – and the last years of the 1940s were very much about establishing their historical place as a recently opened new frontier.

Looking back upon Twentieth-Century Italian Art, it is clear that curators Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and James Thrall Soby had an understanding of the postwar generation that was a work-in-progress, intimating certain a priori notions of modernism that had existed since the fin de siècle. That is to say, Barr and Soby did not see postwar Italian abstraction autonomously, but rather within an aesthetic and ideological matrix that was first enunciated by Barr’s now legendary cover diagram of the catalogue for the 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, but had undergone important revisions in the wake of World War II and the emergence of both the New York School of Abstract Expressionism and the wider phenomenon of global abstraction.1

With this essay, I hope to disentangle these narratives and reinvest postwar Italian art with some of its indigenous specificities, and to understand how its introduction into a paradigm of modernism such as that espoused by MoMA was as much an act of sublimation and obfuscation as it was a recognition of certain key actualities of the works on display. The goal here is not to undo MoMA’s work, but rather to buttress it with documents and historical reframings that have come to light in the decades since. Indeed, this essay will attempt to do double duty: firstly as an augmentation of MoMA’s exhibition, and secondly as an attempt to understand how and why MoMA’s place in this exchange served to reify the broader dialogues surrounding painting and sculpture at midcentury.

A key wrinkle within the writing of this history is the idea of “Neocubism,” a term that in the late 1940s seemed innocuously useful, but has since become something of an overdetermined red herring, and appears infrequently in recent critical discourse. Retrospectively, Neocubism reveals itself to be a misnomer in several ways. Cubism was but one among many sources for these artists, and it should not disproportionately obscure the importance of others. Further, and perhaps most interestingly, neo implies a second, later coming. This, too, is deceptive. Though a generation older than the youngest artists represented in MoMA’s exhibition, Pablo Picasso continued to create influential works understood as Cubist into the 1950s, and he was often spoken of as a contemporary beacon rather than a past source.

Picasso and this new generation of Italian artists were exhibiting contemporaneously, and sometimes in the very same exhibitions. Though the focus of this essay will be on the years leading up to MoMA’s groundbreaking exhibition, the years after witnessed as rich an exchange of influence and ideas from Picasso to Italy, with works such as Guernica (1937), Le Charnier (The Charnel House, 1944–45), and Massacre en Corée (Massacre in Korea, 1951) resonating well into the Cold War.

Additionally complicating this history is the very nature of the exchange. MoMA’s 1949 exhibition was the most impactful view of Italian modernism assembled for American audiences to date. And, as press statements at the time reported, the exhibition’s most recent works were sourced from a trip taken by Barr and Soby to the 1948 Venice Biennale and Rome Quadriennale – hardly a year before Twentieth-Century Italian Art opened at MoMA.

The central, and best documented, concern is how Cubism was absorbed by this new generation of Italian artists. By 1949, Cubism was known and regarded very highly by Italian artists. Indeed, the artists included in this younger generation had revered Picasso’s Guernica since its unveiling. This history adds important nuance to Barr and Soby’s categorization of Italian artists, revealing both its logic and inadvertent oversimplifications.

What the indigenous Italian discourse reveals is some indebtedness to Cubism. Certainly, the formal vocabularies and techniques of Cubism were imitated and integrated in various permutations, and the writings that surround the works reveal more pointedly ideological allegiances to Cubism, particularly in the hands of Picasso, particularly recently. This is, in part, the simple result of Picasso’s works having been ideologically resonant during the Fascist years, when these artists were reaching their early maturity. Though they borrowed much from Cubism’s formal innovations, their history with the movement was determined first, and most profoundly, by its intellectual and political tenets.

This history begins approximately a dozen years before MoMA’s exhibition, during the mid-1930s, when the Milan-based anti-Fascist artists’ group Corrente was pushing against the dominant strains of Fascist culture.2 Artists and intellectuals traveled widely throughout Italy, including Armando Pizzinato to Rome in 1936, where he met Scipione, Renato Guttuso, Mario Mafai, Giuseppe Capogrossi, Roberto Longhi, Cesare Brandi, and Elio Vittorini. The following year, painters Giuseppe Santomaso, Ennio Morlotti, Corrado Cagli, and Afro Basaldella visited Paris. Afro and Cagli, who were working on canvases for the Italian pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, might well have seen Guernica firsthand.3 In 1940, while in Rome, Guttuso received a postcard of the work sent by the critic Brandi, who had seen it in New York.4 Brandi was not the only critic distributing images. In a 1997 interview, militant critic Mario De Micheli recalled that

Picasso was the symbol of the intellectual opposition to Nazi-Fascism, beginning at the time of the war in Spain. His Guernica was the manifesto of the opposition. I went to the art library at Castello Sforzesco [in Milan] and I made myself a series of reproductions of Guernica, which I then distributed to my friends: we carried them at all times in our wallets, as the membership card of an ideal political party.5

To emulate Picasso was to embrace not only the most advanced formal vocabularies of modern painting – remember that this is a generation who came of age under Fascism – but to mobilize them in opposition to the oppressions of artistic freedom by totalitarian regimes, as many had done with their actions of the mid-1930s, including Sassu and Guttuso, who, while in Milan, had stolen Italian military weapons intending to distribute them to partisans before the former’s arrest.6

In 1943, before its windows were shuttered by Fascist authorities and its membership dispersed to various Resistance factions, Corrente issued its “Primo manifesto di pittori e scultori” (First Manifesto of Painters and Sculptors), which claimed:

We look upon Picasso as the most authentic representation of he who has invested himself in life in the most complete sense, but we certainly do not wish to create of him a new academy. We see in the attitude of Picasso a surpassing of the intimism and subjectivism of the expressionists. We see reflected in the canvases of Picasso not his particular struggles, but those of his generation. The images of this painter are provocations and banners for thousands of men.7

These encomia continued into the next years, most notably in De Micheli’s essay “Realismo e poesia” (Realism and Poetry),8 which began circulating in draft form in 1944; in letters to and from artists and critics (including one written on June 2, 1944, from Corrente veteran Renato Birolli to critic Giuseppe Marchiori, which stated: “If Guernica is an indication, we are saved. We will come to understand a historical turning point and how we will be at the head of the renewal. […] We will be among the pioneers of a vital idea”);9 and in articles such as “Communist Picasso,” in the October–November 1944 issue of Communist Party newspaper l’Unità, which reprinted excerpts from an interview originally published in the American weekly The New Masses, and, in the same issue, Guttuso’s “Saluto al compagno Picasso” (Salute to Comrade Picasso), in which he referred to Guernica as “in its essence […] a new work, a cry of revolt and vendetta.”10 Fellow Fronte Nuovo delle Arti member Ennio Morlotti’s “Lettera a Picasso” (Letter to Picasso) was published in the same February 1946 issue of Il ’45 as “Realism and Poetry” and was another call to arms:

We were all convinced that with Guernica painting had put itself in the fire, had returned to [the] depths of life. […]

In 1937 the people called Picasso and Picasso showed the way. […]

Dear Picasso, we were all convinced that with Guernica painting had found the way. This much brought us to absolute conviction. With Guernica we began to want to live, to leave the prisons, to believe in painting and in ourselves, to not feel ourselves alone, arid, the uselessly refused; to understand that also we painters existed in this world to act, that we were men amongst men, that we must receive and give. […]

You continue to break chains […] to defeat sadness, resignation, disorder […] you continue to give clarity, courage, and joy. You affirm and prove that the new civilization of free men exists. And we ask of these free men that they give to you new walls because with your words you can give the new images of the new reality.11

The first tectonic shifts of the postwar period came in the spring of 1946. In the March issue of Numero, in anticipation of a May exhibition organized at Milan’s Caffè di Brera, a group of artists, including some members of Corrente, published the “Manifesto del realismo di pittori e scultori” (Manifesto of realism for painters and sculptors), better known as the “Oltre Guernica” (Beyond Guernica) manifesto.12 Despite its name, this manifesto is not overwhelmingly concerned with visual style or language. Instead, taking a cue from the painting for which it is named, the document emphasizes painting as an act of participation and political engagement.

“Oltre Guernica” coincided with the opening of Pittura francese d’oggi (French Painting of Today) at Rome’s Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, an exhibition that featured a collection of color posters showcasing French modernism from Impressionism to Matisse and Picasso. It was Italy’s first large-scale glimpse of the wellspring of twentieth-century painting that Barr and Soby’s catalogue would refer to as Italian painting’s “supplementary diet.”13

October 1946 witnessed the founding of the Nuova Secessione Artistica Italiana (New Italian Artistic Secession), which would morph into the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti (New Front of the Arts) by November. In January 1947, six months before the group’s debut exhibition at Milan’s Galleria della Spiga, two of its founders, Birolli and Morlotti, endured a trip to Paris that, other than a brief visit with Picasso himself, seems to have been a total failure. The Milan debut was a financial disaster and the last straw with gallerist Stefano Cairola. Nonetheless, it set the groundwork for the group’s appearance at the 1948 Venice Biennale and, thus, MoMA’s 1949 exhibition. Moreover, it was one of the first issuances of a programmatic response regarding the influence of Cubism. Lead critic Giuseppe Marchiori’s catalogue introduction and all but three of the twelve additional essays (one per participating artist) acknowledge the influence of Picasso and/or Cubism, and nearly every artist is positioned within a modernist avant-garde tradition.14

In addressing “Picassism” as a phenomenon, Marchiori in his introduction asks, “Is it possible to rid oneself […] of every memory? And what is tradition if not a record that manifests and affirms itself even in the most ‘revolutionary’ works?”15 Marchiori allows for indebtedness and influence, an acknowledged necessity given the collective estimation of Picasso and the centrality of his artistic and ideological innovations to the formation and membership of the entire Fronte Nuovo.

The artists of the Fronte Nuovo offered permutations of a basic formula: Cubism filtered through individual histories, allegiances, and nuances. Guttuso’s work was heavily contoured by his studies with traditional Sicilian painters of horse-drawn carts, which he merged with his own interpellations of modernism – especially planar color, flattened geometries, and spatial collapse. He had already reached acclaim with works like 1941’s Crocifissione (Crucifixion; figure 1), and he would go on to push deeper into social justice content while moving away from explicit representationalism. Certainly, as early as 1940, Guttuso’s debt to the language of Cubism, through his interest in Cézanne, is evident. It is an early Cubism – the geometric landscapes and planar modelling of the first decade of the 1900s – that is the foundation here, not the more canonical Analytic and Synthetic Cubisms. Also, by 1941 Guttuso had seen images of Guernica. The Cubism of Crucifixion is, more than anything else, this kind of Cubism – the social justice, populist, antitotalitarian Cubism that emerged from the Spanish Civil War a short few years before Italy’s own Resistance erupted.

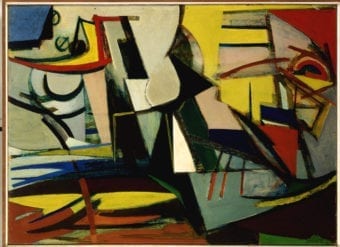

Pizzinato’s abstractions were simultaneously gestural and geometric, marked by a painterly expressionism and a palette reminiscent of Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault, mixing the thick, delineated brushwork of Picasso and Georges Braque with the dynamic geometries of Futurism. Flat areas of color overlap and counteract with more dryly applied areas of paint, the brushstrokes of which echo the dynamism of the intersecting geometries, from within which specific, recognizable imagery emerges.

The works of the Rome-based artist Afro in this moment also reveal the continued influence of Picasso, situating central forms across broadly brushed, loosely geometric backdrops. The linear subdivision of forms into constituent planes recalls works such as Picasso’s 1937 painting La Baignade (On the Beach), in Peggy Guggenheim’s collection.

The endeavors of the Fronte Nuovo were mirrored by those of the Roman group Forma 1, which issued its manifesto in March 1947, leading with a now famous sentence:

We declare ourselves to be Formalists and Marxists, convinced that the terms Marxism and Formalism are not irreconcilable, especially today when the progressive elements of our society must maintain a revolutionary avant-garde position and not give over to a spent and conformist realism that in its most recent examples have demonstrated what a limited and narrow road it is on.16

Wonderfully, Forma 1, which included artists Carla Accardi, Pietro Consagra, Piero Dorazio, Antonio Sanfilippo, and Fronte Nuovo member Giulio Turcato, among others, has received very recent attention within the Anglophone discourse, notably through the work of art historians Juan José Gómez Gutiérrez and Catherine Ingrams.

Following Ingrams, we should look at Forma 1 as a multifaceted reconsideration of the potentials for Italian modernism. Firstly, the movement is a telling, if less known, example of the emergence of abstraction in the postwar context, from Abstract Expressionism to Tachisme and Arte Informale. These associations, however, can be deceptive – as is the case, too, with the Fronte Nuovo. These artists engaged reality subjectively, and their artworks were intended as registrations of psycho-political experiences, manifesting responses to the rapidly changing landscape of mid-1940s Italy, as it shifted from Fascism to occupation, Civil War, invasion, reconciliation, and the republic. Abstraction, in short, was often realistic.

Beyond this, their debt to Russian Constructivism, as Ingrams argues, offers an alternative genealogy to those provided by Cubism, Futurism, or the Fascist ventennio. Ultimately, the results are much like those of the Fronte Nuovo – a vibrant new language built on the synthesis of an increasing inward flow of evidence from prewar European modernism, as filtered through the first-person experiences of an Italian nation that had just survived a bloody, turbulent decade. Unsurprisingly, the works are varied in tenor, resting on the knife’s edge of abstraction and representation, a divide that would become the Achilles’s Heel of its generation.

This division was revisited when, in the issue of Pravda published on August 21, 1947, Picasso was denounced on the grounds that his deformations of the human form were offensive to Soviet views on art.17 This prompted a heated response from Guttuso, who came to Picasso’s defense in the pages of the November issue of L’Avanti.18 In the March 1948 issue of the Rassegna della Stampa Sovietica, Picasso was again criticized, this time by Soviet art historian and critic Vladimir Kemenov.19 These exchanges attest to how high-pitched the debate had become in the rising tensions of the Cold War. Picasso, who would soon be known as one of Europe’s most conspicuous Communist artists, was still subject to the ebbs and flows of the doctrine being shared by Soviet Cominform with its European allies.

The 1948 Venice Biennale, the first such event in six years – the first since the end of the war and the fall of Fascism – would change everything. It offered one of history’s great accumulations of modernist art, and included works by J. M. W. Turner, the Impressionists, Marc Chagall, Rouault, Braque, René Magritte, Henry Moore, Jacques Lipschitz, and Germaine Richier, plus the collection of the recently arrived Peggy Guggenheim, installed in the unused Greek pavilion.

The Biennale commission placed its hopes for the future in the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti.20 Responses were mixed. Luigi Bartolini referred to them as a group of “bean eaters” before demanding: “You degenerates of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, why do you love Picasso’s Cat? Why do you love the bestial obscenity in every one of Picasso’s works, that defiant matador of painting?”21 In many ways, said matador was the patron saint of the 1948 Biennale, a role confirmed by the first Picasso retrospective in Italy. Organized by Rodolfo Pallucchini, it assembled twenty-two paintings dating from 1907 to 1942, and included Pêche de nuit à Antibes (Night Fishing at Antibes; 1939), largely regarded by the Italians as his greatest masterpiece since Guernica.

Fittingly, Guttuso wrote the catalogue’s introduction. Citing Paul Éluard’s dedication in his book on Picasso, Guttuso speaks of the “‘faith of man in man.’ Young Italian painters have and have had this same faith – not abstract, not cultural, but human, of struggle and of hope – in the work of Picasso, during the years of their formation, which were [also] those of Fascism, the years of the progressive and methodic murder of culture, of liberty, of peace.”22 He ends by calling for artists to rise above simplistic formal categories to embrace the larger moral and ideological conflicts at hand: “Picasso brings [us] back to this objective […] to a debate that is no longer between abstract and concrete, or figurative and nonfigurative, or formalism and naturalism, but of human and inhuman, ultimately between ‘good’ and ‘evil.’”23

The group simply couldn’t – and likely didn’t feel obligated to – escape the shadow of Picasso. Enrico Gaifus called them picassini, or “little Picassos,” claiming that “one can declare that Picassism has finished. It has finished badly, with a third-class funeral. It has died lonely.”24 Three weeks later, Marchiori responded: “The few Cubist canvases by Picasso, collected at the Biennale, suffice to explode the legend of Italian ‘Neocubism:’ a denomination invented by certain poorly informed, or even completely blind, denigrators.”25 This statement was set in the middle of a review of Picasso’s retrospective at the 1948 Biennale, wherein Marchiori is most interested in distinguishing the various periods of Picasso’s career so as to emphasize the differences between Guernica and Night Fishing at Antibes, casting the latter as a kind of hallucinatory Surrealism quite distinct from the anguished realism of its predecessor.

Interestingly, Ercole Maselli reviewed the Fronte Nuovo exhibition at that same Biennale, embracing a taxonomic approach much like Marchiori’s. Ultimately, and anticipatory of Marchiori’s objections, Masselli determines that the Cubism of these artists was overdetermined in the critical press: “Another current idea, mistaken, is that these young artists of the Fronte Nuovo are all Cubists or picassini.” His only concession is an admission of the influence of Picasso on Renato Birolli – an assertion without doubt.26

The idiomatic heterogeneity exhibited at the Biennale was abundant. Guttuso exhibited the planar, color-driven studies of labor and life that would appear at MoMA. Armando Pizzinato and his fellow Venetian Emilio Vedova exhibited works driven by energetic explorations of planarity and color shot through with contemporary content and politics. Renato Birolli, Antonio Corpora, and Giuseppe Santomaso offered more moderated abstractions, certainly Cubist in heritage, but also full of other influences and autobiographical references. Giulio Turcato’s work had found the most advanced languages of abstraction, though he would move closer to representation in subsequent years.

This diversity would soon become a liability: in October 1948, on the occasion of the First National Exhibition of Contemporary Art, at Bologna’s Palazzo Re Enzo, Italian Communist Party (PCI) leader and ideologue Palmiro Togliatti called abstraction “scribblings and monstrous things” and demanded that PCI-affiliated artists return to a figuration informed by Soviet Socialist Realism.27

This, effectively, was where things were prior to MoMA 1949. Retrospectively, Barr and Soby’s choices for the postwar period are easy to understand. Guttuso and Pizzinato were leading representatives of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti as well as the interwoven Roman and Venetian scenes. Santomaso and Viani were also members. Included as well were two leaders of Rome’s new school, Afro and Toti Scialoja; the work of the former was, according to MoMA’s Twentieth-Century Italian Art catalogue, a representative of “non-representational” art. Bruno Cassinari, Renzo Vespignani, Marino Marini, Giacomo Manzù, Pericle Fazzini, Emilio Greco, Lucio Fontana, and Marcello Mascherini rounded out the cast.

Obviously, not all of these artists make sense within the notion of “Neocubism.” Nonetheless, the connection of the new Italian avant-garde to Cubism is an unsurprising rhetorical strategy. They themselves had spilled much ink on the importance of Picasso to their agendas, and Picasso was the main attraction at the 1948 Biennale, visited by Barr and Soby, who had built an institution in many ways predicated on the centrality of Picasso and Cubism to all subsequent movements. To reiterate the role of Picasso for Italy was to validate the role of MoMA for modernism – smart and convenient.

The works, however, tell a more diverse story. Guttuso’s Mangiatori di cocomero (Melon Eaters, 1948; figure 2) is typical of this moment. Its broad color planes and collapsed space belie a debt to early pre-Analytic Cubism, and the painting is as much about Cézanne as Guttuso’s Sicilian upbringing and fascination with labor issues.28 Pizzinato sent Cantieri (Dockyards, 1948; figure 3), an excellent representation of his energetic Cubo-Futurist language, synthesizing his interests in painting, the poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky, the industrialization of Venice, and socialist legacies. Santomaso, like Guttuso, was informed by a kind of Fauvist colorism and a tendency towards quotidian content. Viani’s figurative sculptures were most commonly associated with Jean Arp and the ancients. Scialoja’s Fabbriche sul Tevere (Factories on the Tiber), an expressionistic 1946 landscape built of heavily worked paint, is utterly unlike the abstractions that would bring him to greater prominence in the 1950s. Even Afro, the “non-representational” artist, employed a polyglot aesthetic. Whatever this alleged Neocubism was, monolithic it was not.

Within this matrix of making, writing, and exhibiting, there is a more difficult story to tell, of exchange with the United States. What is clear is how much more visible the exchange was after MoMA’s exhibition. The New York exhibition was discussed in an article in Venice’s local paper, Il Gazzettino, that happens to sit in the Biennale archives adjacent to New York Times and New York Herald Tribune articles about a Pizzinato show at Catherine Viviano Gallery in New York. The latter seems to have been 5 Italian Painters, which also included Afro, Cagli, Guttuso, and Morlotti. Afro had a solo show at Viviano immediately after, one of many such links between the gallery and the peninsula. That same summer, the Museo Correr in Venice hosted the Jackson Pollock retrospective that gave birth to his famous “No chaos damn it!” quote.29

The 1950 Venice Biennale featured a Cubism exhibition of works by Picasso, Braque, Juan Gris, and Fernand Léger, organized by Douglas Cooper. In response, Lionello Venturi pointedly juxtaposed Picasso’s legacy with the emergence of Renato Birolli, an ex-Frontista and one of Venturi’s new Gruppo degli Otto (Group of the Eight).30 Similar gamesmanship was afoot in Albert M. Frankfurter’s “International Report” in the September 1950 issue of Art News, for instance in his characterization of Guttuso and Pizzinato:

In the 1948 Biennale, such men as Guttuso and Pizzinato were justifiably hailed as among the best practitioners present of Picassoid abstraction in Italy. Since then the Party issued irrevocable orders for them to stop that sort of thing and paint pictures the masses would understand, pictures or posters of the coming revolution. Now they are here, as arid and dictated as the worst savings-bank mural any capitalist ever dictated. Here is the only place in living art where story-telling subject matter still goes on. The future of art, in other words, depends on which political side wins.31

By mid-1950, equating the styles of Guttuso and Pizzinato was increasingly difficult. Though they both embraced leftist politics and subjects, their visual languages continued to diverge: Guttuso began exploring wobbly-form colorism, while Pizzinato finished off a Cubo-Futurist phase that would soon give way to much more traditional figuration. Of course, to an Anglophone art audience newly familiar with the new landscape of Cold War Italy (Barr and Soby among them), these nuances were still developing. Over the course of the next decade, the exchange would become more constant, intense, and informative, laying the foundation for our current understanding. To quickly summarize an active period about which much work remains to be done, everyone was seeing a lot of everyone else.

Picasso’s 1953–54 retrospective exhibition in Milan and Rome has been the source of much attention.32 To say the least, it was a major success, reminding the Italian public that Picasso’s influence was decades long, had spanned the entire lives of this new generation, and would surely resonate into the future. Similarly, MoMA continued to acquaint itself with the most recent developments in Italian art. The 1950s are littered with overlaps, ranging from the exhibition The Modern Movement in Italy: Architecture and Design (1954), which included, for instance, imagery of Fontana’s 1951 installation at the Milan Triennale, and also the Giuseppe Guerreschi work in the Recent Acquisitions show of 1958. In between were retrospectives of Modigliani (1951), Olivetti (1952), Giorgio de Chirico (1955), and a constant flow of acquisitions from Italian artists ranging from Futurist Umberto Boccioni to Frontista Emilio Vedova. We should also remember that 1958 saw the European and Italian iterations of MoMA’s Jackson Pollock retrospective and the now infamous exhibition The New American Painting.

This momentum, however, was different back in Italy. In the first months of the 1950s, the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti would fragment under the pressure of Cold War politics, forced to choose between the languages of abstraction and realism, largely under the influence of Italian Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti and other party ideologues. Of course, the visual record tells a somewhat different story and, like it had done for decades, Italy’s avant-garde found infinite variations within and between these languages of art. Once the Fronte Nuovo crumbled, it was swiftly replaced by groups such as Lionello Venturi’s Gruppo degli Otto and the by-then global momentum of painterly abstraction, which swiftly came to be associated more with New York than the European examples to which this Italian generation looked for influence.33

By 1958, the generation of the Fronte Nuovo was entering middle age. They had evolved from “The Younger Abstractionists” to the generation soon to encounter, in the 1960s, an utterly different landscape for the arts. That history, to our great benefit, is traced in Germano Celant and Anna Costantini’s book Roma–New York, 1958–1964 (1993).34 Now two and a half decades old, and still a reliable source, it offers an important reminder that we are always compelled to revisit established histories as we plot the path for future work.

Bibliography

Barr, Alfred H., Jr., and James Thrall Soby. Twentieth-Century Italian Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949.

Bartolini, Luigi. “Lettere dalla Biennale di Luigi Bartolini.” Il progresso d’Italia (Bologna). December 2, 1948.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949.” Oxford Art Journal 35, no. 2 (June 2012): 147–69.

Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. “The Politics of Realism: Corrente di Vita Giovanile and the Youth Culture of the 1930s.” Stanford Italian Review 8, no. 1–2 (1990): 139–64.

Bottinelli, Giorgia. “The Art of Dissent in Fascist Italy: The Bottai Years, 1936–43.” PhD diss., The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2000.

Braun, Emily. “The Juggler: Fontana’s Art under Italian Fascism.” In Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold, edited by Iria Candela, 29–39. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019.

Celant, Germano, and Anna Costantini. Roma–New York, 1958–1964. Milan and Florence: Edizioni Charta, 1993.

Costantini, Costanzo. Ritratto di Renato Guttuso. Brescia: Camunia editrice, 1985.

De Micheli, Mario. Arte contro. 1945–1970 dal realismo alla contestazione. Milan: Vangelista Editore, 1970.

De Micheli, Mario. L’Arte stotto le dittature. Milan: Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, 2000.

De Micheli, Mario, ed. Corrente. Il movimento di arte e cultura di opposizione 1930–1945. Milan: Palazzo Reale, 1985.

Duran, Adrian R. Painting, Politics, and the New Front of Cold War Italy. Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate, 2014.

Frankfurter, Alfred M. “International Report.” Art News 49, no. 5 (September 1950): 14–19, 57.

Gaifus, Enrico. “La Biennale riapre i battenti.” Alto Adige (Bolzano), June 6, 1948.

Gendel, Milton. “Guttuso: A Party Point of View.” Art News 57, no. 2 (April 1958): 26–27, 59–62.

Golan, Romy. “The Critical Moment: Lionello Venturi in America.” In Artists Intellectuals and World War II: The Pontigny Encounters at Mount Holyoke College, 1942–44, edited by Christopher Benfey and Karen Remmler, 122–35. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006.

Gutiérrez, Juan José Gómez. “The Politics of Abstract Art: Forma 1 and the Italian Communist Party, 1947–1951.” Cercles. Revista d’història cultural, 15 (2012): 111–35.

Guttuso, Renato. “Pablo Picasso e le guardie bianche.” L’Avanti (Milan), November 13, 1947.

Hunter, Sam. “Contemporary Italians: Guttuso and de Chirico.” The Magazine of Art 43, no. 7 (November 1950): 266–71.

Ingrams, Catherine. “‘A Kind of Fissure’: FORMA (1947–49),” Object, no. 20 (2018): 59–81.

Marchiori, Giuseppe. “Realismo magico di Picasso.” Il mattino del popolo (Venice), June 29, 1948.

Marchiori, Giuseppe. Renato Birolli. Milan: Edizione di Comunità, 1963.

Marchiori, Giuseppe. Il Fronte Nuovo delle Arti. Vercelli: Giorgio Tacchini Editore, 1978.

Maselli, Ercole. “Il Fronte nuovo dell’arte.” Avanti (Rome), October 10, 1948.

Miracco, Franco. “Dalle avanguardie storiche al Fronte Nuovo delle Arti.” In Modernià allo specchio. Arte a Venezia (1860–1960), edited by Toni Toniato, 197–212. Venice: Supernova, 1995.

Misler, Nicoletta. La via italiana al realismo. La politica culturale artistica del P.C.I. dal 1944 al 1956. Milan: Gabriele Mazzotta Editore, 1973.

Morlotti, Ennio. Questa mia dolcissima terra: Scritti 1945–1992. Florence: Casa Editrice Le Lettere, 1997.

Pizziolo, Marina, ed. Corrente e oltre. Opere dalla collezione Stellatelli, 1930–1990. Milan: Palazzo della Permanente, 1998.

Pucci, Lara. “Fighting Fascism in the Kitchen: The Domestic Context in Visconti’s Ossessione and Guttuso’s Still Life Series.” Immediations 3 (2006): 61–77.

Schwarz, Arturo [Tristan Sauvage, pseud.]. Pittura italiana del dopoguerra. Milan: Schwarz Editore, 1957.

Talvacchia, Bette L. “Politics Considered as a Category of Culture: The Anti-Fascist Corrente Group.” Art History 8, no. 3 (September 1985): 336–55.

Togliatti, Palmiro [Roderigo di Castiglia, pseud.]. “Segnalazioni.” Rinascita. Rassegna di politica e cultura italiana 5, no. 11 (November 1948): 424.

Villari, Anna. “Picasso alla XXIV Biennale. La Critica e le reazioni in Italia.” In Picasso 1937–1953: Gli anni dell’apogeo in Italia, edited by Bruno Mantura, Anna Mattirolo, and Anna Villari, 143–53. Rome: Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, 1998.

Vittorini, Elio. Gli anni del “Politecnico.” Lettere 1945–1951. Edited by Carlo Minoia. Turin: Giulio Einaudi editore, 1977.

XXIV Biennale di Venezia. Venice: Edizioni Serenissima, 1948.

How to cite

Adrian R. Duran, “Neocubism and Italian Painting Circa 1949: An Avant-Garde That Maybe Wasn’t,” in Raffaele Bedarida, Silvia Bignami, and Davide Colombo (eds.), Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 3 (January 2020), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/neocubism-and-italian-painting-circa-1949-an-avant-garde-that-maybe-wasnt/, accessed [insert date].

- To this point, and directly related to this topic, is Raffaele Bedarida, “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949,” Oxford Art Journal 35, no. 2 (June 2012): 147–69.

- The individual politics of Corrente and its affiliated artists were, naturally, diverse. And, it is certain that the group took advantages of the connections and protections afforded them by Ernesto Treccani’s father, Giovanni, a senator and count as well as the force behind the Enciclopedia Italiano di Scienze Lettere ed Arti, first published in 1929. Nonetheless, many of those associated with the group – including Aligi Sassu, Renato Guttuso, Emilio Vedova, and Armando Pizzinato – were involved in partisan actions as early as the mid-1930s. For more on Corrente, see Ruth Ben-Ghiat, “The Politics of Realism: Corrente di Vita Giovanile and the Youth Culture of the 1930s,” Stanford Italian Review 8, nos. 1–2 (1990): 139; and Bette L. Talvacchia, “Politics Considered as a Category of Culture: The Anti-Fascist Corrente Group,” Art History 8, no. 3 (September 1985): 336–55. Giorgia Bottinelli’s doctoral thesis, “The Art of Dissent in Fascist Italy: The Bottai Years, 1936–43” (Courtauld Institute of Art, 2000), provides incredibly valuable context. See also the exhibition catalogues Corrente. Il movimento di arte e cultura di opposizione 1930–1945, ed. Mario De Micheli (Milan: Palazzo Reale, 1985); and Corrente e oltre. Opere dalla collezione Stellatelli, 1930–1990, ed. Marina Pizziolo (Milan: Palazzo della Permanente, 1998). I deal with the group in-depth in the first chapter of my book Painting, Politics, and the New Front of Cold War Italy (Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate), 2014. Another fascinating example is that of Lucio Fontana, who was able to play the shifting terrain of Fascism to his advantage. See Emily Braun, “The Juggler: Fontana’s Art under Italian Fascism,” in Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold, ed. Iria Candela (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019), 29–39.

- Their trips to Paris are discussed in Franco Miracco, “Dalle avanguardie storiche al Fronte Nuovo delle Arti,” in Modernità allo Specchio. Arte a Venezia (1860–1960), ed. Toni Toniato (Venice: Supernova, 1995), 204; and Mario De Micheli, L’arte sotto le dittature (Milan: Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, 2000), 119.

- Costanzo Costantini, Ritratto di Renato Guttuso (Brescia: Camunia, 1985), 182 and 214.

- Marina Pizziolo, “Mario De Micheli,” in Pizziolo, Corrente e oltre, 79. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s.

- See chapter 1, “Corrente, Italian Art under Fascism, and the Resistance,” in Duran, Painting, Politics, and the New Front of Cold War Italy, especially 11–12. By the mid-1940s, a number of Corrente-affiliated artists were partisans, including Vedova, Pizzinato, Leoncillo Leonardi, Giulio Turcato, and Mirko Basaldella.

- See Arturo Schwarz [Tristan Sauvage, pseud.], Pittura italiana del dopoguerra (Milan: Schwarz Editore, 1957), 222.

- Originally published in Il ’45 1, no. 1 (December 1946), the text is reprinted in Mario De Micheli, Arte contro. 1945–1970 dal realismo alla contestazione (Milan: Vangelista Editore, 1970), 283–88; and Nicoletta Misler, La via italiana al realism. La politica cultural artistica del P.C.I. dal 1944 al 1956 (Milan: Gabriele Mazzotta, 1973), 240–49.

- Giuseppe Marchiori, Renato Birolli (Milan: Edizione di Comunità, 1963), 34–35.

- Renato Guttuso, “Saluto al compagno Picasso,” l’Unità, December 24, 1944. Quoted in Misler, La via italiana al realism, 196.

- Ennio Morlotti, “Lettera a Picasso,” Il ’45 1, no. 1 (February 1946): 33–34. Reprinted in Ennio Morlotti, Questa mia dolcissima terra: Scritti 1945–1992 (Florence: Casa Editrice Le Lettere, 1997), 21–28.

- “Oltre Guernica” was signed by Giuseppe Ajmone, Rinaldo Bergolli, Egidio Bonfante, Gianni Dova, Ennio Morlotti, Giovanni Paganin, Cesare Peverelli, Vittorio Tavernari, Gianni Testori, and Emilio Vedova. The manifesto was originally published in Numero 2, no. 2 (March 1946). It can also be found in the original Italian in Sauvage, Pittura italiana del dopoguerra, 232–33; and as a photostat of the original in Misler, La via italiana al realismo, 254.

- James Thrall Soby and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Twentieth-Century Italian Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 31.

- The exhibition catalogue Prima mostra del Fronte Nuovo delle Arti (Milan: Galleria della Spiga, 1947) is reprinted in its entirety in Giuseppe Marchiori, Il Fronte Nuovo delle Arti (Vercelli: Giorgio Tacchini Editore, 1978).

- This unpaginated catalogue is reprinted in toto in ibid.

- For more detail on Forma 1, see Catherine Ingrams, “‘A Kind of Fissure’: FORMA (1947–49),” Object, no. 20 (2018): 59–81; and Juan José Gómez Gutiérrez, “The Politics of Abstract Art: Forma 1 and the Italian Communist Party, 1947–1951,” Cercles. Revista d’història cultural, 15 (2012): 111–35.

- See also Guglielmo Pierce, “Fischi a Picasso,” l’Unità, February 2, 1946. Reprinted in Misler, La via italiana al realismo, 236–37.

- Renato Guttuso, “Pablo Picasso e le guardie bianche,” L’Avanti (Milan), November 13, 1947. See also Misler, La via italiana al realismo, 56–59 and 212. The denunciation of Picasso was also the subject of a letter of October 3, 1947, from Elio Vittorini to painter Paolo Ricci, published in Elio Vittorini, Gli anni del “Politecnico.” Lettere 1945–1951, ed. Carlo Minoia (Turin: Giulio Einaudi, 1977), 134–35.

- Kemenov’s critique was published as “La pittura e la scultura dell’Occidente borghese,” in Rassegna della Stampa Sovietica 3 (March 20, 1948). See also Misler, La via italiana al realismo, 212. One imagines that this text is a translation of a Russian original. Indeed, it matches some of the language originally used in Kemenov’s “From Aspects of Two Cultures,” originally published in the VOKS bulletin by the U.S.S.R. Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (Moscow) in 1947; translation available at this link (last accessed October 28, 2019). For a deeper sense of the interchange between the Italian and other Communist Parties, including Moscow’s Cominform, see also chapter 5, “The Communist Politics of Abstraction and the Onset of the Cold War,” in Duran, Painting, Politics and the New Front.

- By the time of the Biennale, the group’s membership included painters Renato Birolli, Antonio Corpora, Renato Guttuso, Ennio Morlotti, Armando Pizzinato, Giuseppe Santomaso, Giulio Turcato, and Emilio Vedova; sculptors Pericle Fazzini, Nino Franchina, and Alberto Viani; and ceramicist Leoncillo Leonardi.

- Luigi Bartolini, “Lettere dalla Biennale di Luigi Bartolini,” Il progresso d’Italia (Bologna), December 2, 1948.

- Renato Guttuso, “Pablo Picasso,” in XXIV Biennale di Venezia (1948), 189. It is also worth noting that Eluard’s writings had been published by the journal of Corrente, to which Guttuso belonged.

- Ibid., 190.

- Enrico Gaifus, “La Biennale Riapre i Battenti,” Alto Adige (Bolzano), June 6, 1948.

- Giuseppe Marchiori, “Realismo magico di Picasso,” Il mattino del popolo (Venice), June 29, 1948.

- Ercole Maselli, “Il fronte nuovo dell’arte,” Avanti (Rome), October 10, 1948.

- Togliatti published the review under his pseudonym. See Roderigo di Castiglia, “Segnalazioni,” Rinascita. Rassegna di politica e cultura italiana 5, no. 11 (November 1948), 424.

- Lara Pucci has done much to shed light on the significance of otherwise innocent-looking domestic objects in these works. See her “Fighting Fascism in the Kitchen: The Domestic Context in Visconti’s Ossessione and Guttuso’s Still Life Series,” Immediations, no. 3 (2006): 61–77.

- Pollock’s response was to a review by Bruno Alfieri, as noted in the Time magazine article “Chaos, Damn It!” (November 20, 1950).

- Venturi’s time in the U.S. in the early 1940s is chronicled in Romy Golan, “The Critical Moment: Lionello Venturi in America,” in Artists Intellectuals and World War II: The Pontigny Encounters at Mount Holyoke College, 1942–44, ed. Christopher Benfey and Karen Remmler (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006).

- Alfred M. Frankfurter, “International report,” Art News 49, no. 5 (September 1950): 14–19 and 57. This Cold War discourse is markedly common in American responses to Italian painting with Communist sympathies. See also Sam Hunter, “Contemporary Italians: Guttuso and de Chirico,” The Magazine of Art 43, no. 7 (November 1950): 266–71; and Milton Gendel, “Guttuso: a Party point of view,” Art News 57, no. 2 (April 1958): 26–27 and 59–62.

- Regarding the Picasso retrospective, see first and foremost Bruno Mantura, Anna Mattirolo, and Anna Villar, eds., Picasso 1937–1953: Gli anni dell’apogeo in Italia (Rome: Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, 1999).

- For more on this context, see chapters 5 and 6, “The Communist Politics of Abstraction and the Onset of the Cold War” and “The Rise of Realism and the Demise of The New Front of the Arts,” in Duran, Painting, Politics and the New Front.

- See Germano Celant and Anna Costantini, Roma–New York, 1958–1964 (Milan and Florence: Edizioni Charta, 1993).