Alberto Savinio and Francesco Clemente: Dilettantes Among Symbols

Elena Salza Elena Salza Alberto Savinio, Issue 2, July 2019https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/alberto-savinio/

This paper investigates the role played by Alberto Savinio’s work in Francesco Clemente’s production within the context of the renewed interest in and appreciation of the artist/writer in the seventies and eighties. It analyzes how Savinio’s literary themes and visual imagery has fostered Clemente’s exploration into the sign, the self, and the otherness. Finally, it explores the extent of the reception of Savinio’s poetics in the pursuit of an individual mythology and symbolic itinerary.

Within the extensive and diversified appreciation of Alberto Savinio by an entire generation of artists, fostered by exhibitions and editorial projects wherein Savinio’s work has been welcomed and reapprehended, the attention shown to his work by Francesco Clemente represents an exemplary case. It is an especially central episode of Savinio’s reception in the context of Italian and American artistic discourse, wherein can be found condensed some of the themes and modalities that have characterized Savinio’s reception. Deriving from the complex nature of the artist/writer’s multifaceted works, it includes both reprints of his books and exhibitions; these returned into circulation literary texts and paintings representing fundamental elements for the understanding of the motives of Savinio’s reappraisal.1

Clemente’s hundred-page illustrated book The Departure of the Argonaut, published with Petersburg Press in 1986,2 in particular, presented Savinio to an American audience by way of the artist’s reflection on La partenza dell’argonauta (1918), translated into English for the first time by George Scrivani, as well as by way of the exhibition organized by the department of prints and illustrated books at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1986. The gestation of Clemente’s book, on which the artist worked in New York at various times between 1983 to 1986, started in April 1983, a few months after the publication of Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco’s “Biographical Notes on a Metaphysical Argonaut,” dedicated to Savinio, in Artforum International.3 This occurrence amplifies the context of The Departure of the Argonaut’s inception, which has to be paired with Clemente’s acquaintance with Savinio’s work in consideration of the writer/artist’s revival in the 1970s. Back then, Savinio’s rediscovery culminated with retrospectives held at Palazzo Reale in Milan in 1976 and at Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome in 1978. At the same time, these exhibitions were both the result of and the reason for that emerging fortune. In fact, it had been taking place over the sixties along with a new recognition of the importance of Pittura metafisica and the renewed study of surrealism. It was further attested to by the reissue by Einaudi Letteratura of Hermaphrodito in 1974, which had been first published by Libreria della Voce in 1918. La partenza dell’argonauta, the second and longest part of the book, already in 1976 had been the subject of a musical theater production of the same title directed by Memè Perlini, which premiered at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino and starred Alba Primiceri – also testifying to the ripple effect created by a new edition of the book.

Although some of the circumstances associated with Clemente’s decision to work on La partenza were occasioned by these events, his drawings for the book essentially constitute an acknowledgment, and the consequential outcome, of his individual journey into the metaphysical, to be comprehended as a deep investment into cultural otherness, symbolism, and mysticism, for which he had found a privileged interlocutor in Savinio.

The Departure of the Argonaut

In the summer of 1986, commenting on the recently printed Departure of the Argonaut, the poet and art critic Gerrit Henry described Savinio’s short novel as “a kind of a poetic, metaphysical and encyclopedically esoteric travelogue.” In announcing the exhibition at MoMA (November 6, 1986 – February 10, 1987), he emphasized the reverence shown by Clemente to Savinio. As reported by Raymond Foye, the editor-at-large of Petersburg Press, who had invited him to contribute to the editorial project, “Argonaut was a kind of a bible to Clemente.” According to Paul Cornwall-Jones, the founder of that publishing house in London, Savinio himself was a god to Clemente.4

Reviewing the MoMA exhibition in Artforum in February 1987, Buzz Spector similarly underlined the link between the two artists by noting the coincidence of Clemente’s year of birth with that of Savinio’s passing, with the artist/writer defined as a “career dilettante traveling the byways of Modernism.”5 Even if by implication, the importance of the relationship was posited in 1985 by Michael Auping when he defined Clemente as a “dilettante among symbols,” in a catalogue accompanying a touring exhibition of the artist’s work in the United States that happened simultaneous to the show at the Museum of Modern Art. Auping’s turn of phrase was intended both to comment on Clemente’s statement about being fascinated by those painters who claim the position of dilettante, and to account for the artist’s quest for images of various artistic sources and their cross-referential use in his exploration of “metaphysical systems.”6 In an empathetical correspondence with the striving mental endeavors shared by the Grandi Dilettanti, namely Nieztsche, Stendhal, and Montaigne, with whom Luciano Di Samosata was in good company according to Savinio,7 the term “dilettante” was actually borrowed from the preface to a posthumous book by Heinrich Zimmer, The King and The Corps, edited by Joseph Campbell for publication in 1948. Zimmer’s explanation of the word, “The dilettante – Italian dilettante (present participle of the verb dilettare, ‘to take delight in’) – is one who takes delight (diletto) in something,”8 when referenced by Auping,9 appears indeed to underline the kind of dialogue Savinio’s legacy promoted. In fact, as Zimmer points out further, the diletto enables not only creative intuition but also gives permission “to be stirred to life by contact with the fascinating script of the old symbolic tales and figures.”10 This allows us to measure the type of engagement through which Clemente dealt with symbolism and mythological materials. They had been amply manipulated and combined by Savinio both in literary and pictorial terms, so they can help us consider what direction Clemente’s previous encounters with La partenza dell’argonauta had offered him.

The exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, curated by Riva Castleman, showed the large livre de luxe on a bookstand with the sequence of forty-eight double pages of lithographs unfolded (figure 1; figure 2). The entire display therefore enhanced the viewer’s/reader’s chance to travel from one page to another, and to traverse the densely visual quality of Savinio’s pictorial writing, to which Clemente’s images indeed respond. The Departure of the Argonaut is not a figurative illustration of Savinio’s narration, if ever it might be even possible to make one; rather, it attests to the broader receptivity of his imagery and poetics, variously channeled into images. The visual response plunges into the “pleasure of the text” – quite literally, in fact, if we consider that precisely the Argo vessel, aboard which the mythical Argonauts sailed, had been used by Roland Barthes in the preface of his Essais Critiques (Critical essays, 1964) as a metaphor for literature.11

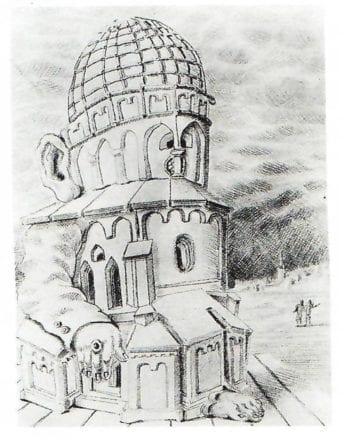

In this regard, the painter reacts to the Argonaut’s journeying with variations and combinations. In correspondence with the third chapter, for instance, we will encounter a multilayered depiction/invention in which Clemente monumentalizes Pinocchio, of whom Savinio wrote of feeling bound to in the brotherhood of unfortunate adventurers. Further, the embedding of architectural elements encompasses Savinio’s story of the search, on his arrival at Taranto, for the kind of “municipal place in every city whose fame precedes it, and which attracts the arriving traveler like a magnet (St. Peter’s in Rome, The Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Statue of Liberty in New York, el palacio del gobernador in Mexico City), and which in this enormous, armed buoy of a town is the Bridge of Two Seas.”12 A similar montage seems to combine anthropomorphism with the merging of forms as explored by Savinio in Cupoluomo (1946; figure 3).

The drawing was published in 1948 in Domus magazine along with a commentary in which he explains the hybridity and the symbolic value of the dome. The work was on view on the occasion of the artist’s retrospective in 1978, and Clemente may have been receptive to the image in many ways, for he had come to Rome to study architecture, and also in light of the text as reprinted under the heading “Cupola” in Savinio’s collection Nuova enciclopedia (New encyclopedia), published by Adelphi in 1977 and titled after the homonym column curated by Savinio in Domus from January 1941 to December 1942.13

In another instance, as a gloss in the tradition of the illuminated manuscript, and in order to indicate to the reader its importance, the artist visually frames the passage in the “Epilogue” related to the description of the Island of Milos, associated by Savinio with “the austerity of certain drawings by Albrecht Dürer and Hans von Thoma, the last representatives of that pictorial symbolism which lies between the mystical and the purely pagan, and in which painters of another type have distinguished themselves, namely Böcklin and Klinger.”14

Almost in reply to the very same ekphrasis and to the metaphorical portrait of the “rocky gray hollow with the appearance of an anatomical landscape,”15 Clemente appears to further interact with the text through visual digressions that suggest we should ponder whether it was because of the Symbolist origins of Savinio’s poetics that his work was reappraised. For an additional lithograph, By the sea (1986), reproduced on the cover of the small-sized trade edition of the book that was published on the occasion of the MoMA exhibition, Clemente turned to an almost Böcklian rendition of the sea, thus meeting Savinio at his very roots in addressing the painters and tradition that were decisive for his education, for instance the mythological theme of Arnold Böcklin’s Triton and Nereid (1874), which appears to animate the dark, mightily scaled waves.

As Giuliano Briganti astutely comments in the catalogue of the exhibition Itinerario mitologico, held at the Galleria dell’Oca in Rome in 1974, which included works by Savinio as well as Böcklin, Giorgio de Chirico, and Sergio Vacchi, that mythic image, understood as symbol, invokes research devoted to the symbolic meaning of mythological themes and archetypes.16 On this same occasion, Savinio’s painting Atlante (1927) offered another conceptual map, so to speak, for cultural navigation, as well as for envisioning a dialogue and travel between contemporaneity and the past, or the antique.

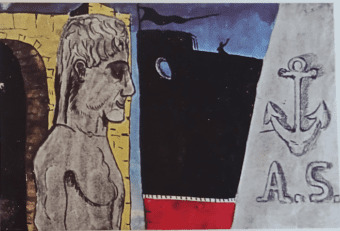

Savinio’s reception was therefore associated with an invitation au voyage, and with an investigation of symbolism in the strict sense. In this critical framework, the theme and the myth of journeying, explored and capitalized by Savinio in La partenza dell’argonauta, is turned by Clemente, in The Departure of the Argonaut, into various maritime elements and symbols. While they carve a pathway towards the same visual semantics offered in Savinio’s painting Le départ des Argonautes (1925–26; figure 4), they also attest to his travel towards symbolic codes. The ship and the inscription of the artist’s initials under an anchor may represent the frame of reference to which belongs a semaphoric alphabet that uses flags to spell Savinio’s name, repeated over a number of pages. Together with the knots, equally recurring, which may similarly pertain to seafaring nautical ropes, or to badges used in heraldry, or to a mnemonic system such as the quipu, these devises appear to expound the subject through symptomatic images.

Making Friends

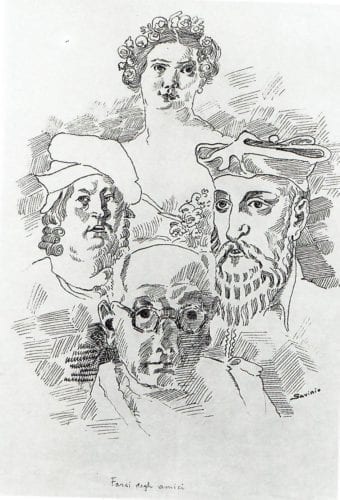

As a result of an exploration further undertaken in the realm of symbolic portrayal, which implies research into both the sign and the self, Clemente’s most evident statement – the clearest anyway – is to be found hidden at the end of the book, in the last folio: a signature in the shape of a heraldic emblem. He meticulously retraced Savinio’s drawing Farsi degli Amici (To make friends, 1943; figure 5), and countersigned it by adding, at the top left, his own portrait to those of the friends Savinio is said to have found: the alchemist/astrologer Paracelso, the seer Nostradamus, and the American dancer Isadora Duncan.

Appearing in the magazine Film in July 1943, associated with the fifth episode of Savinio’s Vita di Enrico Ibsen (Life of Henrik Ibsen),17 that depiction actually relates to the short stories “Nostradamo,” “Isadora Duncan,” and “Primo amore di Bombasto” (Bombastus’s first love), which conclude, in this sequential order, the book Narrate, uomini, la vostra storia, published by Bompiani in 1942, reprinted in 1977, and republished by Adelphi in 1984. The book was translated into English by Marlboro Press in 1988 with the title Operatic Lives, thus treating its fifteen chapters/characters as originating in opera librettos.18 The fancied, fictionalized biographies include also those of Böcklin and Carlo Collodi, and are narrated to create a genealogy of intellectual friends, masters, and ancestors. At the same time literary portraits and self-portraits, they were created according to a strategy apt for mirroring otherness and identity, one of many sprinkled throughout the entirety of Savinio’s oeuvre along with a proliferation of pseudonyms.

If Clemente himself joined Savinio and his amici so as to ratify that he had encountered a kindred spirit, it was a backward validation, standing for a re-marked signature of the long-lasting relationship between the two. In 1978, the very same year in which Savinio’s drawing Farsi degli Amici was exhibited in Rome on the occasion of Savinio’s retrospective, the title was significantly appropriated by Clemente for his own rendition of Farsi degli Amici (1978). Following Savinio’s group portrait, the artist marked out his own four kindred spirits, denoted by emblematic figures and their corresponding names: “Talete” (Thales), “Epimenide” (Epimenides), “Lao-Tze,” and “Kwang-Tze” are credited side by side; Savinio stands next to them, though in watermark. In fact, the writer’s presence is to be felt in noting the position he covered in the intellectual landscape and philosophical discourse promoted by Adelphi’s cultural project. With it the reader is invited to make a pilgrimage to a geographical and mental territory, and to explore the stance assigned to Savinio on a metaphysical and mystical horizon. Its editorial pendulum had in fact swung, in 1973, to the release of a translated version of the Chinese text Tao tê ching: il libro della via e della virtù (The book of the way and its virtue by the Lao Tze),19 and then to the 1978 publication of Giorgio Colli’s La sapienza greca (The Greek wisdom), which includes Thales and Epimenides in its second volume.20 Along this journey the reader would next encounter, in 1975, Savinio’s Maupassant e “l’altro” (Maupassant and “the other”)21 as well as Artemidorus’s Il libro dei sogni (The book of dreams),22 which also foster an investigation into the self and the other, with the inherited philosophical and psychoanalytic traits that have accompanied Savinio’s reception at large.

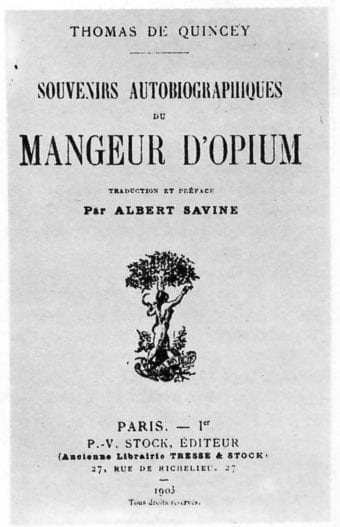

Savinio’s shadow appears also behind Clemente’s Undae Clemente Flamina Pulsae (1978), where an enlarged reproduction is noteworthy of the cover of the 1970 Penguin paperback edition of Thomas De Quincey’s biographical essay collection Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets.23 Indeed, it was in the light of the 1903 French translation of De Quincey’s Souvenirs autobiographiques du mangeur d’opium (Autobiographical Memories of the Opium Eater) by Albert Savine, put forward in the 1978 catalogue (figure 6) as a perhaps accidental coincidence with the pseudonym adopted by Andrea De Chirico,24 that Clemente once showed his appreciation of Savinio. “I think Savinio translated De Quincey into French,” he told Robin White in 1981.25 Despite the mistaken attribution, the remark nevertheless reflected that Savinio’s literary labyrinthine daydreaming was associated with De Quincey’s hallucinatory visions and imaginative faculty of dreaming, the evocative power of which widely nourished the Romantic temperament.

In a continuous and lively meditation related to the concept of otherness and to the theme of the double, Farsi degli Amici was the title of three other works by Clemente, a sort of series wherein further friendships were sealed under the aegis of Savinio’s motto. For Farsi degli Amici, Sol (1980) and Farsi degli Amici, Cy (1980), Clemente staged his self-portraits against backdrops personifying artistic selves, with additional others and initiations assigned to stylistic imitations that symbolize, respectively, portraits of Sol LeWitt and Cy Twombly. Acknowledged as an important catalyst, in the artist’s words, “Twombly was an example of someone who had also sailed away from history into geography.”26 The Mediterranean trajectory with which the American artist Twombly was engaged and his interest in associated mythological themes were in fact not dissimilar to the itinerant existence of Clemente, who further empathized with Savinio’s pendular moves in space and time. On the other hand, the mystical concern and the philosophical investigation claimed by LeWitt in “Sentences on Conceptual Art” (1969)27 may explain the intellectual friendship conveyed by Clemente’s pictorial imitation, for which Norman Dubrow, who donated the work to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1985, suggested a visual source in the detail of a LeWitt wall drawing reproduced on the cover of Artforum in April 1975.28

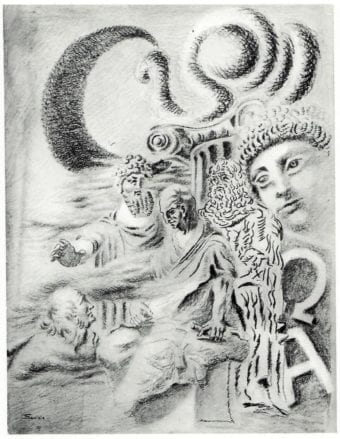

In another work from this group, Farsi degli Amici, Arthur (1980), the exploration of the doppelgänger takes the form of Arthur Schopenhauer, a pivotal figure in both Savinio’s and de Chirico’s cultural education. It was indeed through the German philosopher’s peregrinations in the Indian thinking and his adoption of the Maya concept, appropriated from Hindu philosophy, that Clemente’s fascination with the Eastern aesthetics found its privileged dialogue with Savinio’s polytheistic world – where Western and non-Western myths and religions merge. In 1981, precisely when the Einaudi Supercoralli edition of Hermaphrodito was published, Clemente affirmed, in the fresco L’ermafrodito (1981), his interest in Savinio’s polysexual, polymorphous world. The pictorial representation of the hermaphrodite’s archetype, to which Savinio had also dedicated Il riposo di Ermafrodito (The rest of Ermafrodito, 1944–45), relies on the embodiment of the opposites within one, depicted by way of anatomical duplicity in a physical unity. Such double identity appears also inscribed in the self-portrait of the artist who peers at himself in a looking glass – almost a visual rendition of Jacques Lacan’s study “The Mirror Stage as Formative for the ‘I’ function” (1949). It emphatically appeared, on the other hand, in the italicisation of the last two letters of the artist’s name, “Savinio,” in the frontispiece of the catalogue of the 1967 exhibition held in Turin at Galleria Narciso (figure 7).

Differently conveyed through a split, the duality of female and male occurs again in Clemente’s Hermaphrodite from 1985, during the gestation of The Departure of the Argonaut. Among the images assigned to the masculine part of the androgyne iconography, on the picture’s right lower section a distinctive place appears to belong to Savinio: the “other,” posing in between irony and gravitas, portrayed as a pre-Socratic philosopher wearing tunic and eyeglasses. Actually, Guido Le Noci, in his remembrance of Savinio published among many collected by Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arco in the catalogue for the 1978 exhibition in Rome, recounts that “as the more time passed by, the more his figure had been assuming in my memory the aspect of an ancient wise Greek.”29 Similarly, Carlo Belli’s recollection in the same publication describes him as “elusive, ungraspable, like those Eastern sages who have got their fill of wisdom, and no one knows what else they are doing on earth, since it is clear they have already overcome all worldly things.”30 Both considerations are indebted to the individual mythology/mythography Savinio himself had contributed to in the formulation of his literary texts and in cultivating them visually. The identification with the wisdom of Athena continues, for example, in the severe caricature offered in Autoritratto in forma di gufo (Self-portrait as an owl, 1936), once owned by Le Noci. Along with the Argonaut, a diverse constellation of figures – various divinities, humanized or metamorphosized; metaphysicians and philosophers, from the recent past to the remote – had in fact also offered a platform for inscribing the artist’s poetics. Those figures also shaped the quality of his reception. “Greece has created myths, other myths have been created around her:” this is the introduction to Savinio’s entry dedicated to Anassagora, in the fifth part of Nuova enciclopedia, published in Domus in 1941 (figure 8) and reprinted in book form in 1977.31 An invitation to a reinterpretation and rejuvenation of myth that Clemente enthusiastically accepted.

Bibliography

Alberto Savinio. Turin: Gissi Galleria d’arte, 1967. Exhibition catalogue.

Auping, Michael, Jean-Christophe Amman, and Francesco Pellizzi. Francesco Clemente. New York: Abrams, 1985.

Briganti, Giuliano. Itinerario mitologico. Boecklin, De Chirico, Savinio, Vacchi. Rome: Galleria dell’Oca, 1974. Exhibition catalogue.

Calasso, Roberto. L’impronta dell’editore. Milan: Adelphi, 2013.

Colli, Giorgio, ed. La sapienza greca, 2. Milan: Adelphi, 1978.

Clemente, Francesco. Francesco Clemente: affreschi, pinturas al fresco. Madrid: Fundación Caja de Pensiones, 1987. Exhibition catalogue.

Clemente, Francesco, and Rainer Crone. Francesco Clemente: Pastelle 1973–1983. Munich: Prestel, 1984. Exhibition catalogue.

Clemente, Francesco, and Raymond Foye. Francesco Clemente: India. Pasadena, CA: Twelvetrees Press, 1986.

Clemente, Francesco, and Pamela Kort. Clemente, shipwreck with the spectator, 1974–2004. Milan: Electa, 2009. Exhibition catalogue.

Clemente, Francesco, Ann Percy, Raymond Foye, Stella Kramrisch, and Ettore Sottsass. Francesco Clemente: Three Worlds. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art; New York: Rizzoli, 1990. Exhibition catalogue.

De Quincey, Thomas. Recollections of the Lakes and Lake Poets, edited with an introduction of David Wright. Harmondsworh: Penguin Books, 1970.

Dubrow, Norman. “Clemente’s Farsi Degli Amici, Sol.” Drawing: The International Review Published by The Drawing Society 3, no. 5 (January–February 1986): 105.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio. “Biographical Notes on a Metaphysical Argonaut–Alberto Savinio.” Artforum International (January 1983): 46–53.

Fagiolo dell’Arco, Maurizio, Daniela Fonti, and Pia Vivarelli. Alberto Savinio. Rome: De Luca, 1978. Exhibition catalogue.

Grewe, Andrea, and Sabine Kleymann. Savinio europäisch. Berlin: E. Schmidt, 2005.

Henry, Gerrit. “‘The Departure of the Argonaut’—A Departure for Clemente.” The Print Collector’s Newsletter 17, no. 3 (July–August 1986): 87–89.

Savinio, Alberto. Hermaphrodito. 1974. Reprint, Turin: Einaudi, 1981.

Savinio, Alberto. Maupassant e “l’altro.” Milan: Adelphi, 1975.

Savinio, Alberto. Narrate, uomini, la vostra storia. Milan: Bompiani, 1942. Reprint, Milan: Adelphi, 1984.

Savinio, Alberto. Nuova enciclopedia. Milan: Adelphi, 1977.

Savinio, Alberto. “Nuova enciclopedia 5. Anassagora.” Domus 162 (June 1941), 63.

Savinio, Alberto. Operatic lives. Translated by John Shepley. Marlboro, VT: Marlboro Press, 1988.

Savinio, Alberto. “Savinio si commenta.” Domus 229 (1948), 34–35.

Savinio, Alberto, and Francesco Clemente. The Departure of the Argonaut. Translated by George Scrivani. New York: Petersburg Press, 1986.

Spector, Buzz. “Departure of the Argonaut, Museum of Modern Art.” Artforum 25, no. 6 (February 1987): 114.

Varnedoe, Kirk, Richard Serra, Francesco Clemente, and Barnet Newman. “Cy Twombly: An Artist’s Artist.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 28 (Autumn 1995): 163–79.

White, Robin, and Francesco Clemente. Francesco Clemente. Oakland, CA: Crown Point Press, 1981.

Worthen, Amy N. The Departure of the Argonaut: Prints by Francesco Clemente. Des Moines, Iowa: Des Moines Art Center, 2015.

Zimmer, Heinrich R. The King and the Corpse: Tales of the Soul’s Conquest of Evil. Edited by Joseph Campbell. New York: Pantheon Books, 1948.

How to cite

Elena Salza, “Alberto Savinio and Francesco Clemente: Dilettantes Among Symbols,” in Alberto Savinio, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 2 (July 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alberto-savinio-and-francesco-clemente-dilettantes-among-symbols/, accessed [insert date].

- This paper derives from a larger presentation titled “Argonauts, Hermaphrodites, and Other Post-Modernist Myths: Alberto Savinio’s Reappraisal in the 1970s and 80s” that I delivered at the symposium on Alberto Savinio at the Center for Italian Modern Art, New York, April 28, 2018. The research was conducted as part of my 2017–2018 fellowship at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York.

- Presentations of and literature on Francesco Clemente’s The Departure of the Argonaut include an exhibition organized at the John Brady Center Print Gallery at the Des Moines Art Center, curated by Amy N. Worthen (February 20–May 17, 2015), and an exhibition at MADRE – Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donna Regina in Naples, curated by Pamela Kort (May 29–October 12, 2009). See Amy N. Worthen, The Departure of the Argonaut: Prints by Francesco Clemente (Des Moines, Iowa: Des Moines Art Center, 2015). On Savinio and Clemente, see Pamela Kort, Clemente: Shipwreck with the Spectator 1974–2004 (Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2009), 17–57; and Madgalena Holzhey, “Le molte verità. Alberto Savinio un die italienishe Transavanguardia,” in Savinio europäisch (Berlin: E. Schmidt, 2005), 103–19.

- Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, “Biographical Notes on a Metaphysical Argonaut—Alberto Savinio,” Artforum International (January 1983): 46–53.

- Gerrit Henry, “‘The Departure of the Argonaut’—A Departure for Clemente,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter 17, no. 3 (July–August 1986): 87.

- Buzz Spector, “Departure of the Argonaut, Museum of Modern Art,” Artforum 25, no. 6 (February 1987): 114.

- Michael Auping, “Fragments,” in Francesco Clemente (New York: Harry Abrams, 1985), 11. The book accompanied an exhibition of Clemente’s work that started at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida, in October 1985, and traveled to five additional venues, concluding at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in March 1987.

- The expression is used by Savinio in the introduction to Dialoghi e saggi (Dialogues and essays) by Luciano di Samosata, published in 1944 by Bompiani with notes and illustrations by Savinio, and reprinted by Bompiani in 1983. It is included in Alberto Savinio, Scritti dispersi 1943–1952 (Milan: Adelphi, 2004).

- Heinrich Zimmer, “The Dilettante Among Symbols,” in The King and the Corpse: Tales of the Soul’s Conquest of Evil (New York: Pantheon Book, 1948), 2.

- “In a basic sense, Clemente is what Heinrich Zimmer calls a Dilettante Amongst Symbols. As Zimmer points out, the dilettante – Italian dilettante (present participle of the verb dilettare, ‘to take delight in’) is in this sense ‘one who takes delight in symbols, like conversing with them, and enjoys with them continually in mind’.” Michael Auping, “Fragments,” 12.

- Zimmer, “The Dilettante Among Symbols,” 5.

- “Being of literature; for it the desire to write is merely the constellation of several persistent figures; what it left to the writer is more than an activity of variation and combination: there are never creators, nothing but combiners, and literature is like the ship Argo whose long history admitted of no creation, nothing but combinations; bracketed with an unchanging function, each piece was nonetheless endlessly renewed, without the whole ever ceasing to be the Argo.” Roland Barthes, preface to Critical Essays, trans. Richard Howard (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2009), xvii.

- Alberto Savinio, The Departure of the Argonaut, trans. George Scrivani (New York: Petersburg Press, 1986). Italics in original.

- Alberto Savinio, “Savinio si commenta,” Domus 229 (1948), 34–35. See Alberto Savinio, “Cupola,” in Nuova enciclopedia (Milan: Adelphi, 1977), 106–08.

- Savinio, The Departure of the Argonaut, unpaginated.

- Ibid.

- Giuliano Briganti, Itinerario mitologico. Boecklin, De Chirico, Savinio, Vacchi (Rome: Galleria dell’Oca, 1974), unpaginated.

- Alberto Savinio, “Vita di Enrico Ibsen,” Film. Settimanale di Cinematografo, teatro e radio (July 10, 1943), 5. Vita di Enrico Ibsen was published in six parts in Film, from May 15–July 24, 1943, and reprinted by Adelphi in 1979.

- Alberto Savinio, Narrate, uomini, la vostra storia (1942; repr., Milan: Bompiani, 1977; Milan: Adelphi, 1984); Alberto Savinio, Operatic lives, trans. John Shepley (Marlboro, VT: Marlboro Press, 1988).

- Lao Tze, Tao tê ching: il libro della via e della virtù, ed. J. J. L. Duyvendak, trans. Anna Devoto (Milan: Adelphi, 1973).

- Giorgio Colli, La sapienza greca, 2: Epimenide, Ferecide, Talete, Anassimandro, Anassimene, Onomacrito, Teofrasto: Opinioni dei fisici (Milan: Adelphi, 1978).

- Alberto Savinio, Maupassant e “l’altro” (Milan: Adelphi, 1975). Adelphi’s reprint in 1975 followed the reprinting of Maupassant e “l’altro” in 1960, promoted by Giacomo De Benedetti in the series Biblioteca delle Silerchie and directed for Il Saggiatore.

- Dario Del Corno, ed., Artemidoro. Il libro dei sogni (Milan: Adelphi, 1975).

- Thomas De Quincey, Recollections of the Lakes and Lake Poets, edited with an introduction of David Wright (Harmondsworh: Penguin Books, 1970).

- Daniela Fonti, “I tre volti di Savinio,” Alberto Savinio (Roma: De Luca, 1978), 44. The catalogue also reproduced the frontispiece of Thomas De Quincey’s Souvenirs autobiographiques du mangeur d’opium that was translated by Albert Savine and published in Paris in 1903. See Alberto Savinio (Roma: De Luca, 1978), 45.

- Robin White in conversation with Francesco Clemente, in Francesco Clemente (Oakland, CA: Crown Point Press, 1981), 6.

- Francesco Clemente, “Cy Twombly: An Artist’s Artist,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 28 (Autumn 1995): 170.

- “Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.” Sol LeWitt, “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” Art-Language, no. 1 (May 1969): 11.

- Norman Dubrow, “Clemente’s Farsi Degli Amici, Sol,” Drawing: The International Review published by The Drawing Society 3, no. 5 (January–February 1986): 105.

- Guido Le Noci, letter dated January 1976, in Alberto Savinio (Roma: De Luca, 1978), 30. Translation the author’s.

- Carlo Belli, Alberto Savinio (Roma: De Luca, 1978), 23–24. Translation the author’s.

- Alberto Savinio, “Nuova Enciclopedia 5. Anassagora,” Domus 162 (June 1941), 63 (the entry is accompanied by the drawing Anassagora [1931–32]); reprinted as “Anassagora,” in Alberto Savinio, Nuova enciclopedia. Translation the author’s.