Upper East side, two minutes walk from Central Park. At the seat of the Ukrainian Institute of America, a grand turn-of-the-century mansion on 79th Street at the corner of Fifth Avenue, there is on view, since last fall, an ensemble of works of art realized by the sculptor Alexander Archipenko. This is a group of sculptures, paintings, and drawings – very heterogeneous for the quality and the dates of each work—gathered around 1950 by Augustin and Maria Sumyk, collectors and friends of Archipenko. Their son, Dr. Borys Sumyk, decided some time ago to lend these works to the Ukrainian Institute for a period of ten years, to make them accessible to a broader public.

It was interesting for me to discover this exhibition while here in NYC as a Fellow at the Center for Italian Modern Art [add link], because I did my PhD thesis on Archipenko, one of the leading actors of 20th-century international sculpture. Moreover, in New York there are some of the rare surviving examples of the works that Archipenko realized in Paris in the early 1900s, held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. I was excited to get to see these works in the flesh.

Born in Kiev in 1887, Archipenko arrived in New York in 1923, after an early European sojourn, and he spent the rest of his life in the United States. The Archipenko Foundation in Bearsville, NY [add link], run by his second wife, Frances Archipenko Gray, testifies nowadays to his American presence and promotes scholarship on his work.

Interested in the arts from childhood, Archipenko attended art schools in Kiev and Moscow. Nevertheless, his temperament, curious and inventive, led him to abandon suddenly traditional academic training in favor of a direct and lively observation of works of art shown in public museum and private collections. He might had been impressed by the paintings by Paul Gauguin hung on the walls of the dining room of the collector Sergei Shchukin in

Moscow and attracted by the creative winds that blew from Europe at that time. In 1908 he left Russia to move to Paris, living there until the outbreak of WWI. In the French capital, the sculptor became friends with many artists who were determined to revolutionize the language of art. Fernand Léger, the brothers Duchamp-Villon, Henri Le Fauconnier, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, František Kupka, Joseph Csáky, and Robert and Sonia Delaunay were just some of the artists—known as “Cubists”—with whom Archipenko exhibited between 1910 and 1914. And at the same time, Guillaume Apollinaire and André Salmon supported these artists’ innovative investigations in the columns of the French magazines.

In 1912-1914, sculptors, in a fertile dialogue with painting and through the medium of drawing, took another step forward to free sculpture from its language of traditional, naturalistic rendering. At that time, Archipenko went even further in his experimentation with the human figure. He developed a vocabulary of linear form, simplified and sinuous, creating a succession of convex and concave parts. In this way, he defined the silhouette and the volume of the figure and at the same time gave a very dynamic character to the whole construction. This is the case with the “Madonna of the Rocks” (1912): a red-painted plaster now in the collection of MoMA [please add link here]. The work was originally purchased by Fernand Léger in 1912, then acquired by the Perls Galleries in 1960, and it entered MoMA nine years later.

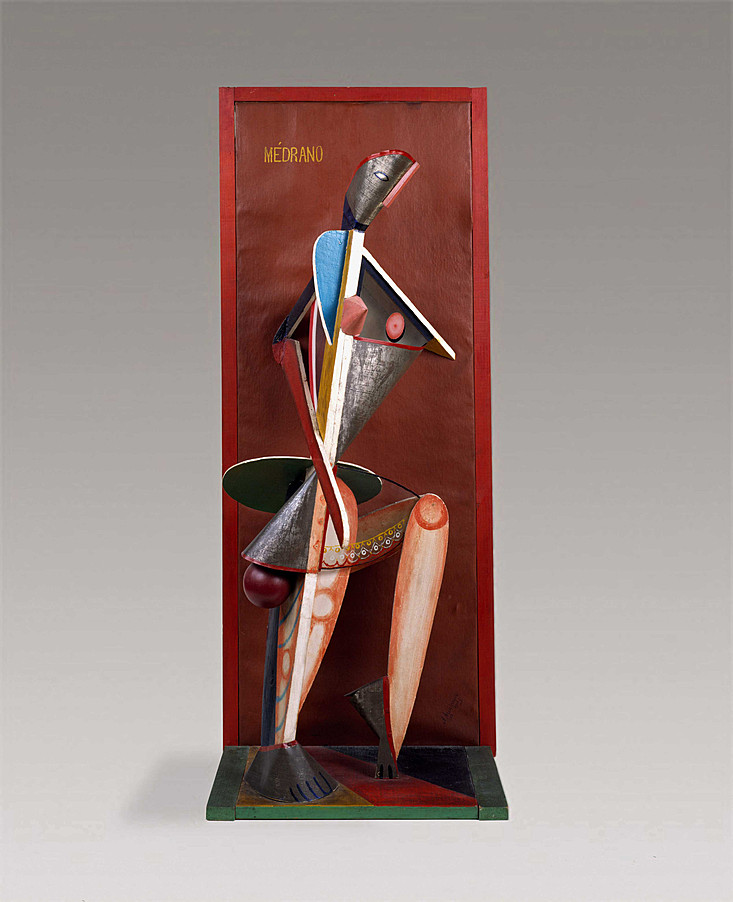

In another aspect of his work, around 1913-14 the artist realized some polychrome plasters and several other constructions using recycled materials like tin, glass, wood, and oilcloth. These works, inspired by the world of the circus and merry-go-rounds, instilled the depiction of the human figure with a living character, a mobile nature, and a mechanical aspect. We can see this in “Carrousel Pierrot” (1913) and “Medrano II” (1913-14), now at the Guggenheim [please add links]. These were originally bought by Alberto Magnelli in Paris in the spring of 1914 for the Florentine collection of his uncle, and then acquired by the Guggenheim Museum between 1955 and 1957, thanks to the taste and the taste and the foresight of the director James Johnson Sweeney.

In March 1914, these works caused a scandal at the annual Salon des Indépendants because of the ironic irreverence of their subject, features and materials, as testified by a caricature drawing published in the French magazine “Le Bonnet rouge”. Here “Medrano II” and “Carrousel Pierrot” appear with “The Gondolier”, another creation by Archipenko. Apollinaire, on account of his defense of the artist in the columns of “L’Intransigeant,” was immediately fired from the editorial staff of the magazine.

The sculptures by Archipenko held in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum are not currently on view. As a scholar interested in the artist, however, I was able to make an appointment to see the works in the museum’s off-site storages, alongside works of art by other artists contemporary to Archipenko. This moment was one of the most thrilling of my time in the United States. This is certainly one of the great privileges reserved to an art historian: to be able to see a group of works of art, selected from the database of the museum, live in person, in a very private exhibition organized for you by the staff of the museum. The works of art are there, in front of you, and you can study them very closely, from every point of view! You can embrace the entire form with your gaze, observe the color and the material, see the signs of age and the hand of the artist who engraved the date and his signature. This experience is essential for the understanding of a work, and to place that both within the corpus of an artist, and in relation to works made by others. At the end of my visit, walking home along the busy streets of New York City, I let these new ideas and just-seen images flood my imagination, grateful to the museums’ staffs and to Alexander Archipenko, too. In these last years, the study of his work has enabled me to move from Florence to Paris, and from Paris to New York. I wonder how many other destinations await me?