In the Sign of Tuscan Artistic Tradition: The Creative Experience of Marino Marini at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, 1917–1923

Michele Amedei Michele Amedei Marino Marini, Issue 5, May 2021https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/marino-marini/

This article investigates Marino Marini’s training at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze on the basis of unpublished documents, preserved in the historical archives of that institution. What emerges from those documents is that Marini was initially enrolled in 1917 in the so-called Scuola di Ornato, under the guidance of Augusto Burchi and, in particular, Galileo Chini. Subsequently, from January to October 1922, Marini attended the Scuola di Incisione with Celestino Celestini, whose results were a series of engravings partly analyzed by Mario De Micheli and Giorgio Guastalla in 1990. Finally, from the fall of 1922 to the summer of the next year, Marini took part in the sculpture lessons held at the Accademia by Domenico Trentacoste, one of the most famous Italian sculptors of the time. Although scholars have always given little importance to Marini’s training at the Accademia of Florence, the legacy of that course has left a trace in the work of the great sculptor through different perspectives. On the one hand, the Accademia initiated him into the practice of engraving and sculpting. On the other, the training with professors such as Galileo Chini convinced Marini to look with interest at the models of Tuscan Renaissance art even in the late 1920s, after the end of a long training phase that lasted a total of six years.

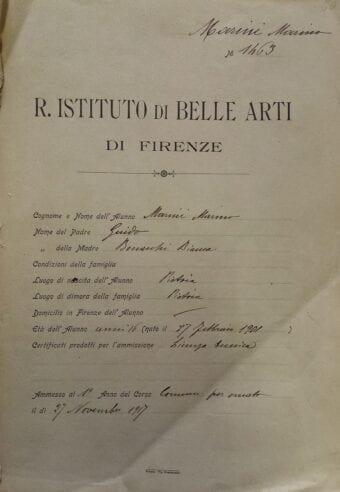

In the many studies on Marino Marini, little space is given to the artist’s training at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze,1 which took place between November 1917 and July 1923.2 The present study’s goal is to deepen our understanding of Marini’s artistic training through the analysis of unpublished documents held in the academy’s archive (figure 1), and to expand upon Laura Vannucchi’s exploration of the topic in a recent article that draws primarily on documentation preserved by Marini’s heirs.3

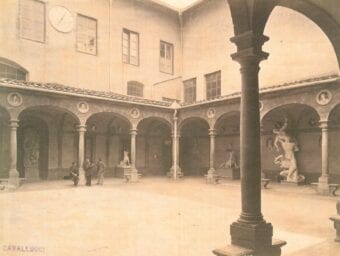

The Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze (figure 2), founded in 1784, was one of the most important Italian artistic institutions of its era when Marini studied there, at the Scuola di Ornato, with his twin sister Egle (1901–1983), a painter and poet. He benefitied from the guidance of two teachers:4 Augusto Burchi (1853–1919), professor at the academy from 1891 to the year of his death, and Galileo Chini (1873–1956), a pioneer of Art Nouveau painting and ornamentalism in Italy and abroad.5 From January to October 1922, during his last year at the Scuola di Ornato, Marini also took an engraving course taught by Celestino Celestini (1882–1961),6 Italian engraver.7 Lastly, from October 1922 to the summer of 1923, Marini enrolled in the second year of Speciale Scultura, under Domenico Trentacoste (1859–1933), a central figure in the history of the academy at Florence, to whom we will return later.8

It is not clear from primary sources why Marini took such a varied and multifaceted set of courses. His choice of the Scuola d’Ornato, in which he was enrolled for five years as of November 27, 1917, may have been due to the possibilities offered by a profession that responded to the growing demand for ornamentalists, or better still, decorators, in early twentieth-century Tuscany. With the rise of Art Nouveau at the end of the nineteenth century, the work of ornamentalists such as Chini was particularly sought after in Pistoia, Marini’s birthplace; the local bourgeoisie loved to live in buildings characterized, both inside and out, by an exasperated and superfluous decorativism inspired by natural forms.9

Nor do biographical sources tell us why Marini decided, between January and October 1922, to combine his studies at the Scuola d’Ornato with Celestino Celestini’s engraving course. What is certain is that while attending that course, his interest in sculpture increased. Only by deepening what he had done with Chini, whose Ornato course also included exercises aimed at improving students’ skills in bas-relief, was Marini able to enroll directly in the second year of Speciale Scultura – he skipped the first two years of the sculpture course by passing a single admissions exam in the summer of 1922. After the reforms of Giovanni Gentile (1875–1944) in the early 1920s, the academy’s program provided aspiring sculptors with three hours of teaching a week for a course that was structured as follows: a first foundation year, called Comune Scultura, in which students gained practice with plaster copies of anatomical details (eg., limbs and heads); a second level, 1° Speciale Scultura, intended to refine the young artist’s skills with training in the face and back, and in sketching compositions; and finally, a third level, 2° Speciale Scultura, in which the student continued his exercises in composition while copying and reinterpreting the nude figure (male or female) plastically (in bas-relief and in the round).

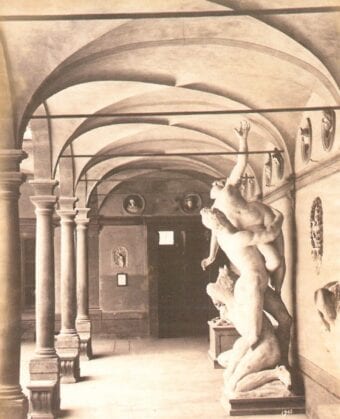

In 1976, Marini’s twin sister, Egle, published a biographical note expressing her negative memories of the years Marini spent at the academy.10 She had attended the same Ornato courses as her brother for five years in a row, achieving excellent results.11 However, her memories should be read with caution, not so much because they were written many years later, after the narrated events, but because they demonstrate the abyss separating the sensibility of Marini and Egle even during the time they spent at the Accademia, an environment that Egle judged as “dead.” According to her written account, the classrooms at the academy – some of which were being used to receive the wounded from the front at the time of the Marinis’ enrollment – were hidden “behind dark arcades” (figure 3). They were shadowy and ghostly theater spaces for a form of teaching she considered dead and buried:

We are in the climate of war. In makeshift classrooms, behind dark arcades, there was the accumulated dryness of the autumn “nineteenth century,” with the cold plaster cast draped over it, the flesh model, standing, holding a rod like a halberd, and residual ghosts of truly dead authors.12

Egle’s pages on her brother’s life convey a dark and gloomy impression of the academy’s environment, in contrast to the blinding light of the ancient Mediterranean civilizations (especially the Etruscan, which her brother would become so devoted to). According to Egle, these civilizations were already illuminating Marini’s mind and heart in 1918, distracting him from his teachers’ lessons. During that year, the twins’ second at the Ornato, Marini could be described, recalled Egle, as a “closed pebble” (ciottolo chiuso):

He tastes the instruments of work; he pursues images extraneous to the indications preached [by the masters of the academy]; he ignores the technical awkwardness; he starts out slim, genuine and secret, relaxed and free.13

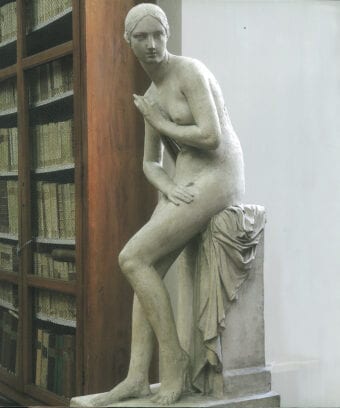

The documentation preserved at the academy’s archives includes the testimonies of professors. Their assessments of Marini, and of the works he made during his Florentine education and in the years immediately following, seem to tell a different story from Egle’s, from 1976. They do not describe Marini as distracted by “images” distant from those proposed by his teachers. They tell us that his authenticity (genuinità), expressed in his final exams (pictorial and sculptural) and judged excellent by professors such as Chini or Trentacoste,14 was experienced through an education that did not deny the work done by the “ghosts” of “truly dead authors” of the academy – that is, the professors or students who, since its founding in 1784, had made the academy the most important and well-respected artistic institution in Florence (e.g., Luigi Pampaloni [1791–1847] and Lorenzo Bartolini [1777–1850]). Masterworks in plaster by these artists, including Venere che entra in bagno (The Toilet of Venus, 1836) and the so-called La Donati (c. 1846), were scattered around the academy alongside casts of the greatest masterpieces of antiquity and the fifteenth century,15 thus communicating to the academic community, including aspiring artists such as the Marinis, the artistic and cultural continuity of a local tradition rooted in the Tuscan Renaissance. In fact, Luigi Stiattesi’s plaster copy of La Donati (c. 1846; figure 4), Bartolini’s lost masterpiece,16 and Pampaloni’s Venere che entra in bagno, a work that at the end of the nineteenth century was considered an example of “modern plastic art” by Cleomane Marini (1853–1917), professor at the Scuola di Ornato e figura before Burchi and Chini,17 were conceived by the two sculptors after looking at masterpieces of Renaissance and Neoclassical statuary, e.g., Venere al bagno (1575), by Giambologna (1529–1608), preserved in the Grotta del Buontalenti, in the Giardino di Boboli, in Florence, and Venere italica (1804-1812), by Antonio Canova (1757–1822), held in Florence’s Galleria Palatina and inspired in turn by undisputed models of antiquity such as the so-called Venere Medicea, at the Galleria degli Uffizi.

Since 1784, the academy in Florence had in fact been a beacon in the training of young people, both local and foreign, who wanted to learn in an environment that had been set up, from the very beginning, to educate the next generation in the creation of works to express the social and civil function of art in relation to Florentine tradition.18 During the years in which Marini attended the school, those principles did not fail him. On the contrary, they were renewed in the light of a period of educational reform that took place thanks to the involvement of personalities such as Galileo Chini, appointed “Professore Aggiunto” in the Scuola di Ornato in 1917 (the year that Marini and Egle enrolled in his course). As Susanna Ragioneri points out in a forthcoming article,19 Chini’s arrival at the academy marked a turning point in the reorganization of the institution’s teaching, especially in the Scuola di Ornato, which had been directed by the elderly Burchi.

Up until that point, the academy had developed as a teaching body in which fragmentation between the various artistic schools and the lack of relationships between them marked a split not only within the various specialities promoted by the Accademia but also with respect to the problems posed by contemporary artistic research. From the very first year of his teaching, Chini organized his classes in the terms of a teacher-pupil relationship reminiscent of the Renaissance workshop. Moreover, Chini instilled in his students the idea that there were no expressive or hierarchical distinctions between the various artistic practices. In this regard, he was the spokesman for a then-common feeling in Italy: the convinction, in Ragioneri’s words, that there was a need for the students enrolled at the academy to develop a language capable of merging “major and applied arts, referring to the latter no longer in an exclusively classical and historicist sense” but as “craft knowledge linked to the extraordinary variety of the Italian territory, and with the manifest intention of broadening the ethics of beauty by including it in the industrial development of the time.”20

Read in the light of this educational current, Marini’s choice to combine the Scuola di Ornato courses with his experimentation in engraving and then sculpture (his first works in painting, according to Egle, date back to around 1918),21 appears justified. Marini found strength in his close relationship with a teacher like Chini, who “with modernity of intent and with a true love of art” encouraged his students to pass the end-of-year exams “with simplicity of means,” as well as “vigor of intellect and tenacity of will.”22 In his first years at the academy, Marini may have begun to develop an apparently “closed pebble” (ciottolo chiuso) sensibility, as Egle remembered,23 but this did not prevent him from absorbing what his teachers imparted. In the time that he studied under Chini and his school, he quietly nurtured a fairy-tale imagination, applying “color inlays” in pure, crystalline tones to the head of a bird, insects (“analyzed like jewels”), and the vegetable world;24 these melted into a neo-fifteenth-century idiomatic language that was vaguely familiar to the contemporary style of the master Chini. Proof of this can be seen in photographs, now in private collections, of a group of lost studies for bas-relief decorations (perhaps produced for his Plastica d’Ornato exams); these studies, discovered by Laura Vannucchi and mentioned in a forthcoming article by her, were almost certainly made around 1920, the year in which, among other things, Marini earned the esteem of Chini, who judged him and Egle as among the best students enrolled in his class. These studies suggest Marini’s absorption of a modern sensibility akin to Chini’s. At the time, Chini was seduced by fifteenth- and sixteenth-century artists’ ability to tie architectural structure and plastic decoration together as a harmonic whole, with allegorical and ancient figures in front of regular architectures of classical taste.25

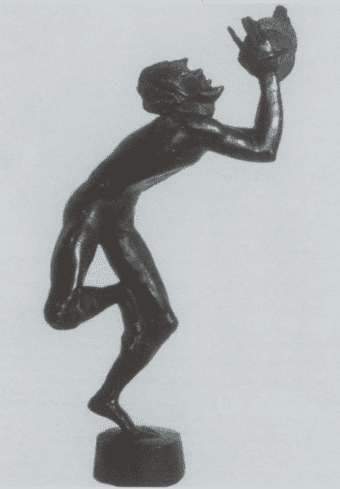

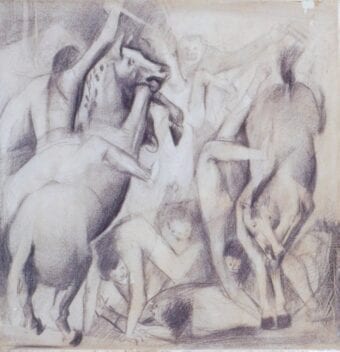

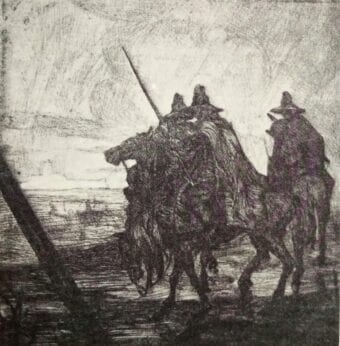

Marini’s interest in Tuscan artistic tradition seems to surpass any other model of reference in his student years, including the great archaic statuary, especially Etruscan, he could see when visiting the nearby Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Florence. Marini seems to have cultivated a deep, visceral interest in the impressive early Tuscan sculptors of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, beyond the exercises he was subjected to by the masters at the Accademia. Susanna Ragionieri notes that even in later years, around 1925, when his autonomy from his teachers could have oriented him towards a plasticism far different from theirs, Marini was not distracted by the purity of artists such a Andrea Pisano (c.1290–1348 or 1349) or Jacopo della Quercia (1374–1438).26 Their works became undisputed models for Marini, for example, in 1925, in the composition and theme of the Putto che suona (Playing Putto; figure 5), preserved in Florence: the silhouette of the player is inscribed in a bas-relief within a frame of hexagonal format, sculpted in a synthesis and stylistic essentiality that refers back to Andrea Pisano’s hexagonal panels placed to decorate Giotto’s Campanile in Florence. Moreover, in the same years Marini found inspiration in other Tuscan Renaissance masters, e.g., Antonio del Pollaiolo (1429–1498) and Piero della Francesca (c. 1406 or 1412–1492). Marini looked to Pollaiolo, particularly his bronze Ercole e Anteo (Hercules and Antaeus, c. 1475), to compose his Piccolo satiro (Young Satyr, 1926), especially the position of the satyr’s head and the composition of the slender and elastic body (figures 6 and 7). Finally, he was indebted to Piero della Francesca for the composition of one of his drawings preserved in the Uffizi, the so-called Zuffa di cavalieri (Knights Fighting, c. mid-1920s), which clearly depends on Piero’s pictorial models in the Cappella Bacci, Chiesa di San Francesco, in Arezzo (figures 8 and 9).27

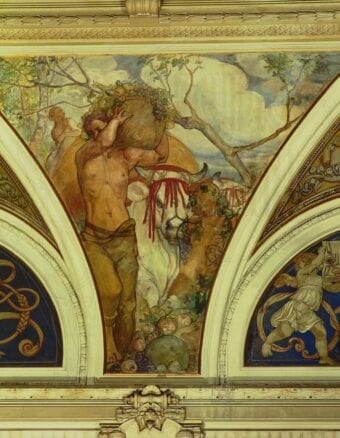

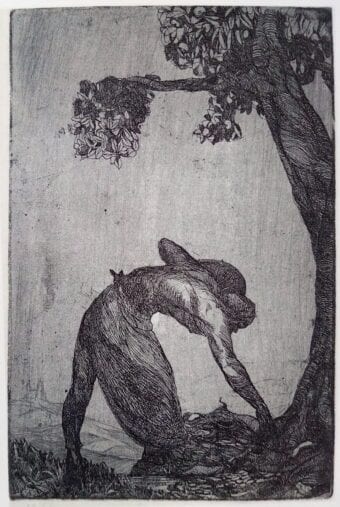

In sum, closeness to Chini seems to have pushed students such as Marini and his sister to study nature apropos of Italian and specifically Tuscan artistic traditions. In fact, it has been noted that for the decorations of the Palazzo Comunale of Montecatini (not far from Pistoia),28 datable to 1918, Chini composed the figures inserted in the complex and articulated decorative apparatus (which includes images representing the personification of the four seasons) using a style that resembles the great “compositional naturalness” of sixteenth-century Italian masters, e.g., Michelangelo (1475–1564), reinterpreted through the lens of the most celebrated exponents of the Viennese Secession (figures 10 and 11).29 Marini did not remain indifferent to the charms of that pictorial language, and as soon as he enrolled in Celestini’s engraving course he composed a series of engravings, among them L’Estate (Summer, 1922; figure 12), which seems to depend on Chini’s decorations at Montecatini,30 particularly in the harmonious relationship between the personification of Summer (a half-naked man bent over to pick seasonal fruit) and the tree of luxuriant flowers.

L’Estate was made in a class, that of the Scuola di Incisione, in which one could breathe an atmosphere of “freedom” and “joy” combined with an “obstinate rigor” worthy, according to Celestini himself, of the best Renaissance workshops.31 Here, Marini nourished his desire to experiment with graphic techniques by tackling themes that, as well as finding inspiration in the contemporary research of the master Chini, were also influenced by the sensitivity of the young professor Celestini.

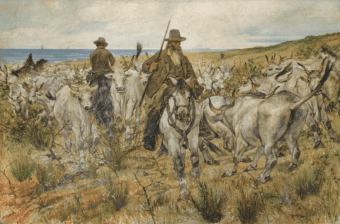

Deeply invested in a Tuscan graphic tradition rooted in fifteenth-century Florence, Celestini encouraged his students to experiment with techniques such as, and above all, etching. Celestini worked in absolute respect of the teachings of his master, the Macchiaiolo painter Giovanni Fattori (1825–1908), who was also an engraver.32 Marini, more and more inclined to undertake a polyvalent and polyhedral artistic direction, proved open to Celestini’s suggestions in creating engravings; many of these works by Marini, including I butteri (Tuscan Herders, 1922), are clearly inspired by Fattori’s paintings (figures 13 and 14).33 Fattori taught at the academy in Florence from the 1870s until the year of his death,34 and was one of the greatest interpreters of modern Italian pictorial research in relation to subjects inspired, for the most part, by the wild landscapes of the Maremma, inhabited by the butteri.35

In the summer of 1922, towards the end of his last year at the Ornato and the engraving course, Marini suddenly decided to further what he had learned in the plastic arts by taking the exam that allowed him to skip the 1° Speciale Scultura and earn a place on the 2° Speciale Scultura. The professor of sculpture Trentacoste was very different from Chini and Celestini in both age and culture, having been born in Palermo in 1859. An authority at the academy, he remained deeply attached to the Florentine institution even after reaching retirement in 1926. After that year, he continued as director of the academy, a role that he had been awarded in 1915, just one year after his appointment as professor, at age fifty-six. After his initial training in Palermo, Trentacoste had moved to Paris in 1880, remaining there until 1895, when he decided to move permanently to Tuscany, motivated by his attachment to Italy, and especially to Florence and Renaissance art.36 His professional success began thereafter. In 1895, at the first Venice Biennale, Trentacoste exhibited the Derelitta (Forsaken; figure 15). To his contemporaries this work appeared indebted to Lorenzo Bartolini’s Fiducia in Dio (Trust in God, 1833), one of the most admired marbles of nineteenth-century Tuscan art, and indeed Italian. That work’s fame, international in breadth, had earned its author the chair of sculpture at the academy in Florence in 1839.37

In Italy, Trentacoste brought to completion some works begun during his long stay in France, among them, Ofelia (c. 1893; whereabouts unknown) and Niobide (1896; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea).38 These last works, successfully exhibited in their time in important exhibitions in Venice, Milan, and Turin, were seen as interpreters39 of that cultural trend known as the Renaissance de l’idéalisme, or “rebirth of idealism,” that in France found its theoretical foundation in the writings on aesthetics by Jean-Marie Guyau (1854–1888), whose book L’art au point de vue sociologique (Art from a Sociological Point of View, 1889) was very successful in Italy.40 Originally an end-of-the-century antipositivist reaction intended to claim the “reason of the heart” over that of science, in the figurative field the Renaissance de l’idéalisme promoted the primacy of beauty along with the civil, social, and spiritual content of art, avoiding any escape from reality or symbolist abstruseness. This sensibility stayed with Trentacoste for the whole of his life. He was committed to art’s diffusion in the light of the harmony between major and minor arts, which found him in full agreement with young artists like Chini, whom he was eager to enlist and sponsor (even at ministerial levels), securing his appointment as a teacher at the Scuola di Ornato.

It is easy to imagine that Marini got along with the authoritative Trentacoste – a professor of advanced age, laconic, sometimes grumpy, and of few words. At the end of the year, Trentacoste rewarded Marini with a grade of 9/10. He lived on in Marini’s memory as an honest and conscientious teacher who could be criticized for his didactics, but not as a sculptor. As Marini himself confessed to his fellow student, Bruno Catarzi (1903–1996), he drew cues and ideas from Trentacoste’s sculpture. What exactly Trentacoste thought of the young Marini is not clear. The only evidence of his judgement is the aforementioned grade, which can only be read to represent an assessment of a single, specific work Marini, whose subject remains unknown. Moreover, there is no evidence of letters exchanged between them. The only message delivered by Marini to his teacher is a business card on which he congratulates Trentacoste on his appointment as Accademico d’Italia, in 1932.41

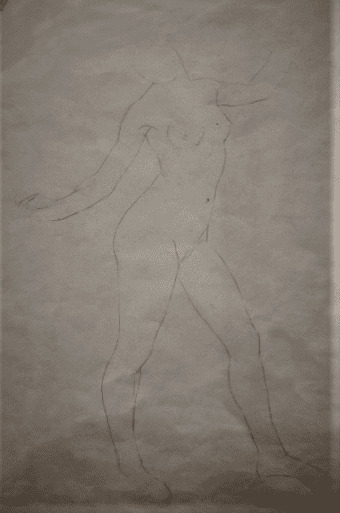

As Giovanna De Lorenzi notes, the legacy of Trentacoste in Marini’s work should be seen from different points of view, not least the latter’s professional loyalty and absolute respect for and dedication to his art. By looking at Trentacoste’s works, Marini learned about the beauty and harmony of the female nude. In particular, he would have looked at the beautiful bas-reliefs of nude allegorical figures made by Trentacoste at the beginning of the 1900s for the Italian Parliament; their poses resemble those that inspired a group of drawings sketched by Marini at the beginning of the 1920s, when he was attending Trentacoste’s course (figures 16 and 17). Moreover, let us not forget that Trentacoste (and before him, Aristide Maillol, 1861–1944) gave his personal interpretation to a subject very dear to Marini: Pomona.

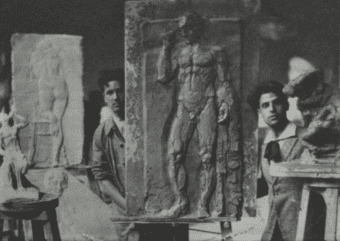

Finally, as De Lorenzi argues also, the attention with which Marini treated his sculptural surfaces finds its origin in Trentacoste’s works, and from his teacher Marini may have derived his lifelong interest in materials other than marble, notably bronze, which Trentacoste used in many works (e.g., his medals, created until the early 1920s).42 The education provided to Marini by Trentacoste was essentially based in modeling, in which he was an unsurpassed artist. Believing that art cannot be separated from the technical skills of the artist, Trentacoste taught “craft” by alternating lessons in working a marble surface with others focused on bronze casting, and he encouraged his students to work in the round as well as in bas-relief, at both large and small scale. On the one hand, the results would have been bas-reliefs such as the one immortalized by a photograph of Marini in the company of his companion Bruno Catarzi in the Scuola di Scultura between 1922 and 1923 (figure 18). The subject of the bas-relief (a female nude seen from behind) recalls, according to De Lorenzi, certain rough-hewn versions made by Trentacoste years earlier, for the allegories of the towers of Montecitorio in Rome (Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Florence). Marini’s many medals or plaques should also be mentioned here, some of which were created even after he had abandoned the school of Trentacoste. In 1928, for example, at the Prima mostra provinciale di Pistoia, Marini exhibited the aforementioned Putto che suona and five medals (now lost), possible demonstrating a natural continuity from the teachings of Trentacoste.43

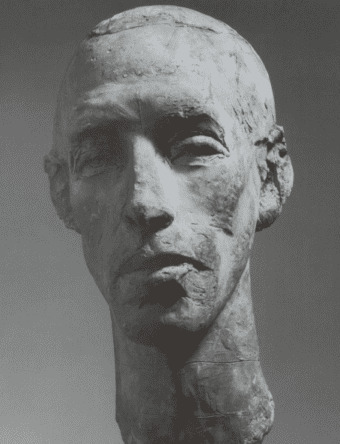

Trentacoste was also a master of portraiture, that genre of which Marini was so fond. In making portraits, Trentacoste would not have wanted Marini to avoid rendering naturalistic details – in absolute respect of the teachings of early Renaissance sculptors. Marini was attentive to this lesson even years later. In the 1920s, he rethought the pure forms of the most “archaic” Florentines of the early fifteenth century, sharpening that “inner mastery” in the rendering of the portrait through a form that the Italian poet and art critic Renato Fondi (1887–1929) defined, in 1927, as “limpid,” charged with a communicative force dictated by the “light caricatured hue.”44 Marini sculpted many portraits that year, including some exhibited at the 1928 Pistoia exhibition – e.g., his portraits of the painter Vieri Freccia (1908–1969; now at the Fondazione Marino Marini Pistoia) and of Angelo Lanza (figure 19). These, according to Fondi, were “tenacious efforts to rediscover that complex expression, naive and cunning at the same time, typically rigid and dynamic, refined and unripe, which distinguishes our fifteenth century.”45

On completion of the sculpture examination in the summer of 1923, whose results were evaluated as excellent by Trentacoste and by an external commission composed of Augusto Rivalta and Raffaello Romanelli, Marini’s long training at the Florentine Academy, begun six years earlier, came to a close. Following his time at the artistic institution, he joined a group of writers and artists in Pistoia, some of whom he had met at the academy. They included Alberto Giuntoli (1901–1966), the future husband of Egle.46 Marini collaborated with local writers in the foundation of the magazine Solaria and the so-called dei puri group.47 From then on, his relationship with the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze and its teachers almost ceased to exist: aside from requesting his attendance certificate for the sculpture course of the 1922–23 academic year, Marini undertook a path that would lead him to refer rarely to the academy and its milieu.

Bibliography

Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016.

Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, 2 Vols. Florence: Mandragora, 2017.

Amedei, Michele. “Per un’introduzione agli scultori stranieri all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze nell’Ottocento.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, 235–56. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016.

Amedei, Michele. “Pittori esteri all’Accademia di Belle Arti fra il 1815 e il 1850.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, vol. 1, 283–96. Florence: Mandragora, 2017.

Annigoni, Pietro, ed. Celestino Celestini. Incisore e pittore. Florence: Olschki 1964.

Baboni, Andrea, ed. Giovanni Fattori. La poesia del vero. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Baboni, Andrea, ed. Giovanni Fattori tra epopea e vero. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Bacchini, Maurizia Bonatti, Filippo Bacci di Capaci, Valerio Terraroli, and Paolo Emilio Antognoli, eds. Orizzonti d’acqua tra pittura e arti decorative. Galileo Chini e altri protagonisti del primo Novecento. Pontedera: Bandecchi & Vivaldi, 2018. Exhibition catalogue.

Bellesi, Sandro. “Scultura e scultori all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze in età lorenese: normative, insegnamenti, collezioni d’arte, concorsi, commissioni, restauri e altro.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, 21–85. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016.

Bellesi, Sandro. “La Scuola di Pittura e i suoi protagonisti dalla fondazione dell’Accademia alla restaurazione lorenese.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, vol. 1, 45–90. Florence: Mandragora, 2017.

Bellini, Paolo, “Contributi per la conoscenza dell’opera incisa di Celestino Celestini (1882–1961).” In Celestino Celestini 1882–1961, incisioni, edited by Francesca Benucci, 9–16. Perugia: Benucci 1992. Exhibition catalogue.

Benzi, Fabio, and Mariastella Margozzi, eds. Galileo Chini: dipinti, decorazioni, ceramica, teatro, illustrazione. Milan: Electa, 2006. Exhibition catalogue.

Benzi, Fabio. Galileo Chini. La decorazione del Palazzo Comunale di Montecatini Terme. Florence: Maschietto Editore, 2019.

Bietoletti, Silvestra. “La Scuola di Scultura all’Accademia di Firenze dall’Unità alla prima guerra mondiale.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, 87–120. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016.

Bietoletti, Silvestra. “La Scuola di pittura all’Accademia di Firenze 1815–1860.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, vol. 1, 91–139. Florence: Mandragora, 2017.

Cassese, Giovanna. “La funzione didattica dei gessi in Accademia dal passato al futuro.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, 131–50. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016.

Catalli, Fiorenzo, and Giuliano Centrodi. Monete e medaglie. Da Domenico Trentacoste a Enzo Scatragli. Firenze : Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana, 2012. Exhibition catalogue.

Cresti, Carlo. “Episodi liberty a Pistoia.” Il tremisse pistoiese 6 (1981): 25–28.

De Lorenzi, Giovanna. “Domenico Trentacoste e la rinascita d’interesse per la medaglistica.” Antichità Viva 27 (1981): 29–38.

De Lorenzi, Giovanna. “Su alcune sculture di Domenico Trentacoste.” Artista (1990): 192–207.

De Lorenzi, Giovanna. “Firenze, la Francia e le arti figurative fra Ottocento e Novecento.” Artista (2007): 58–73.

Dini, Francesca, Fernando Mazzocca, and Giuliano Matteucci, eds. Fattori. Venice: Marsilio, 2015. Exhibition catalogue.

Dominici, Laura. “Luigi Mazzei e la decorazione a Pistoia tra ‘Liberty’ e ‘Déco.’” In Le età del Liberty in Toscana, edited by Maria Adriana Giusti, 113–17. Florence: Octavo, 1996. Conference proceedings.

Egle Marini 1924–1968. Edited by Luana Cappugi. Milan: Electa, 1990. Exhibition catalogue.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Auguste Rodin e gli scultori italiani (1889–1915). I.” Prospettiva 89–90 (1998): 40–73.

Fondi, Renato. “Marino Marini incisore e scultore.” Rassegna grafica, nos. 20 and 21 (November–December 1927).

Frulli, Cristina. “Appunti per una memoria delle opere di Antonio Canova e dei ‘marmi Elgin’ nei calchi in gesso dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, 197–217. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016.

Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti. Catalogo generale, vols. 1–2. Florence: Sillabe, 2008.

Guastalla, Giorgio, ed. Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato dell’Opera grafica (incisioni e litografie), 1919–1920. Livorno: Ed. Graphis arte, 1990.

Marini, Egle. “Nell’ombra serena.” In Omaggio a Marino Marini, 17–28. Milan: Silvana Editoriale d’Arte, 1976.

Panerai, Sibilla. “Le decorazioni di Galileo Chini in Toscana: un itinerario tra neomedievalismo e Jugendstil.” In Galileo Chini e la Toscana, edited by Alessandra Pucci Belluomini and Glauco Borella, 53–69. Milan: Electa, 2010. Exhibition catalogue.

Paolucci, Fabrizio. “La raccolta dei gessi di statuaria classica dell’Accademia di Belle Arti fra XVIII e XIX secolo.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, 173–96. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016.

Petrucci, Francesca. “La Scuola di Pittura dall’Unità d’Italia alla Prima Guerra Mondiale.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, vol. 1, 141–90. Florence: Mandragora, 2017.

Pratesi, Mauro. “Celestino Celestini e i primi anni della Scuola di Incisione fiorentina.” In Celestino Celestini 1882–1961, incisioni, edited by Francesca Benucci, 17–23. Perugia: Benucci 1992. Exhibition catalogue.

Prima mostra provinciale d’arte. Pistoia: Arte Stampa, 1928. Exhibition catalogue.

Pucci Belluomini, Alessandra and Glauco Borella, eds. Galileo Chini e la Toscana. Milan: Electa, 2010. Exhibition catalogue.

Ragionieri, Susanna. “Natura trasfigurata e mito nella Toscana degli anni Venti e Trenta.” In La Toscana e il Novecento, edited by Francesca Cagianelli and Rossella Campana, 161–75. Pisa: Pacini, 2001. Exhibition catalogue.

Ragionieri, Susanna. “Il circolo di Lanza del Vasto.” In Arte del Novecento a Pistoia, edited by Carlo Sisi and George Tatge, 40–63. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2007. Exhibition catalogue.

Ragionieri, Susanna. “‘Senza che l’astratto perda purezza, né la vita plenitudine’: il rapporto di Lanza del Vasto con gli artisti toscani alla fine degli anni Venti.” In Lanza del Vasto e le arti visive, edited by Manfredi Lanza, 22–38. Fasano: Schena, 2007. Conference proceedings.

Scardino, Lucio. “Una placchetta bronzea di Domenico Trentacoste.” Ferrariae Decus 12, (1997): 51–53.

Videtta, Giuliana, and Anna Gallo Martucci, eds. I luoghi di Giovanni Fattori nell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, passato e presente. Florence: Pagliai, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Videtta, Giuliana. “Giovanni Fattori e l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze.” In Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, edited by Sandro Bellesi, vol. 2, 179–90. Florence: Mandragora, 2017.

- The topic of this article is different from the one initially conceived, which concerned Marino Marini’s visit to New York in 1950. My stay in New York as a CIMA fellow was abruptly interrupted after only two months due to the Covid-19 pandemic, forcing me to suspend my investigation of that topic. Consulting with Laura Mattioli, whom I thank, I thus decided to pursue a different aspect of Marini’s life: his training at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. In my research into this new topic I am grateful to Susanna Ragionieri and Giovanna De Lorenzi for sharing with me their unpublished materials regarding Galileo Chini and Domenico Trentacoste. I am also thankful to Daniele Mazzolai, archivist at the Florence Accademia, for his prompt help, and to Flavio Fergonzi, Massimiliano Ballerini, Ursula Armstrong, Nicol Mocchi, and Claudia Daniotti for their help and suggestions.

- Only Mario De Micheli has partially examined Marini’s training at the Accademia di Belle Arti, in the article “L’idea, il segno, l’immagine,” which introduces Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato dell’Opera grafica (incisioni e litografie), 1919–1920, ed. Giorgio Guastalla (Livorno: Ed. Graphis arte, 1990). See especially pages 9–11.

- The article will be included in the forthcoming volume L’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze nella prima metà del ‘900, ed. Valeria Bruni, Mauro Pratesi, Susanna Ragionieri, and Giandomenico Semeraro.

- Archivio Accademia Belle Arti di Firenze (hereafter quoted as AABAFi), Alunni, Iscrizioni, 1905–1922, no. 1463. Between 1911 and 1913, Chini painted the decoration of the throne room at the royal palace of King Rama V in Bangkok.

- See Galileo Chini. Dipinti, decorazioni, ceramica, teatro, illustrazione, ed. Fabio Benzi and Mariastella Margozzi (Milan: Electa, 2006); Galileo Chini e la Toscana, ed. Alessandra Pucci Belluomini and Glauco Borella (Milan: Electa, 2010); Orizzonti d’acqua tra pittura e arti decorative: Galileo Chini e altri protagonisti del primo Novecento, ed. Maurizia Bonatti Bacchini, Filippo Bacci di Capaci, Valerio Terraroli and Paolo Emilio Antognoli (Pontedera: Bandecchi & Vivaldi, 2018).

- See Mauro Pratesi, “Celestino Celestini e i primi anni della Scuola di Incisione fiorentina,” in Celestino Celestini 1882–1961, incisioni, ed. Francesca Benucci (Perugia: Benucci 1992), 17–23; Pietro Annigoni, Celestino Celestini: incisore e pittore (Florence: Olschki 1964); and Paolo Bellini, “Contributi per la conoscenza dell’opera incisa di Celestino Celestini (1882–1961),” in Celestino Celestini 1882–1961, 9–16.

- See AABAFi, Verbali Esami, Sessione Estiva e Autunnale 1920–21, Sessione di Ottobre 1920–21, Verbale Scuola d’incisione all’acquaforte gennaio 1922, Verbale degli esami di ammissione per l’incisione all’acquaforte – Sezione di Gennaio 1922, no. 2. Marini’s admission to the school through an exam dates to January 4, 1922.

- AABAFi, Alunni, Iscrizioni, 1905–1922, no. 1609. See Giovanna De Lorenzi, “Domenico Trentacoste e la rinascita d’interesse per la medaglistica,” Antichità Viva 27 (1981), 29–38, and “Su alcune sculture di Domenico Trentacoste,” Artista (1990), 192–207; Lucio Scardino, “Una placchetta bronzea di Domenico Trentacoste,” Ferrariae Decus 12, 1997, 51–53; Flavio Fergonzi, “Auguste Rodin e gli scultori italiani (1889–1915). I,” Prospettiva 89/90 (1998), 40–73; Giovanna De Lorenzi, “Firenze, la Francia e le arti figurative fra Ottocento e Novecento,” Artista (2007), 58–73; Monete e medaglie: da Domenico Trentacoste a Enzo Scatragli, ed. Fiorenzo Catalli and Giuliano Centrodi (Firenze : Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana, 2012). Giovanna De Lorenzi explores the relationship between Trentacoste and the Accademia in Florance in “Domenico Trentacoste: ‘maestro amatissimo,’” which will be included in the forthcoming volume mentioned in note 3. I thank Giovanna De Lorenzi for giving me the opportunity to read the article in advance; its information has been fundamental to my understanding of Trentacoste’s role at the Accademia.

- See Carlo Cresti, “Episodi liberty a Pistoia,” Il tremisse pistoiese 6 (1981): 25–28; and Laura Dominici, “Luigi Mazzei e la decorazione a Pistoia tra ‘Liberty’ e ‘Déco’,” in Le età del Liberty in Toscana, ed. Maria Adriana Giusti (Florence: Octavo, 1996), 113–17.

- Egle Marini, “Nell’ombra serena,” in Omaggio a Marino Marini (Milan: Silvana Editoriale d’Arte, 1976), 17–28.

- AABAFi, Alunni, Iscrizioni, 1905–1922, no. 1464.

- “Siamo in clima di guerra. In aule scolastiche di fortuna, dietro portici oscuri, c’era l’accumulato seccume dell’‘ottocento’ autunnale, col freddo calco di gesso drappeggiato, il modello di carne, in piedi, che impugna un’asta come un’alabarda e fantasmi residui di autori veramente morti.” Egle Marini, “Nell’ombra serena,” 18. All translations, unless otherwise stated, are the author’s.

- “Egli assaggia gli strumenti di lavoro; insegue immagini estraneo alle indicazioni predicate [dai maestri d’Accademia]; ignora gl’impacci tecnici; si avvia snello, genuino e segreto, disteso e libero.” Ibid.

- In the first three years of the Scuola d’Ornato, Marini achieved excellent results in the main disciplines (the grades are reported in AABAFi, Alunni, Iscrizioni, 1905–1922, no. 1463). For example, in the 1918–19 academic year, Marini reached 30/30 cum laude in Ornato; 30/30 cum laude in Figura and 30/30 in Plastica d’Ornato. For the academic year 1919–1920, his grades were as follows: Ornato 30/30 cum laude; Figura 30/30; Plastica d’Ornato 30/30 cum laude. Finally, in the academic year 1920–1921: Ornato 30/30 cum laude; Figura 27/30; Plastica d’Ornato 30. Moreover, for his final exam in sculpture (July 1923), Marini obtained the highest judgment from the commission, surpassing Augusto Chini, Giovanni Boldarin, and Tarquinio Lardarin. Trentacoste gave Marini’s work a grade of 9/10, while the external commission, composed of Augusto Rivalta (1837–1925) and Raffaello Romanelli (1856–1928), gave him a grade of 10/10 (see the document in ABBAFi, Verbali di esami, 1922/1923, Sessione estiva, Verbale d’esame di scultura per il 2° anno medio [corso speciale], Sessione di Luglio 1923). The topic of the final exam is unclear in the documentation.

- On the history of the academy, from its birth to the early 1900s, see Sandro Bellesi, “Scultura e scultori all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze in età lorenese: normative, insegnamenti, collezioni d’arte, concorsi, commissioni, restauri e altro,” and Silvestra Bietoletti, “La Scuola di Scultura all’Accademia di Firenze dall’Unità alla prima guerra mondiale,” in Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, ed. Sandro Bellesi (Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2016), 21–85, 87–120. See also Sandro Bellesi, “La Scuola di Pittura e i suoi protagonisti dalla fondazione dell’Accademia alla restaurazione lorenese,” Silvestra Bietoletti, “La Scuola di pittura all’Accademia di Firenze 1815–1860,” and Francesca Petrucci, “La Scuola di Pittura dall’Unità d’Italia alla Prima Guerra Mondiale,” in Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, ed. Sandro Bellesi (Florence: Mandragora, 2017), vol. 1, 45–90, 91–139, and 141–90. On the plaster-cast collection at the Accademia di Belle Arti, see Giovanna Cassese, “La funzione didattica dei gessi in Accademia dal passato al futuro,” Fabrizio Paolucci, “La raccolta dei gessi di statuaria classica dell’Accademia di Belle Arti fra XVIII e XIX secolo,” and Cristina Frulli, “Appunti per una memoria delle opere di Antonio Canova e dei ‘marmi Elgin’ nei calchi in gesso dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze,” in Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Scultura 1784–1915, 131–50, 173–96, and 197–217.

- Bellesi, “La Donati,” in ibid., 350–52.

- Annarita Caputo, “Venere che entra al bagno,” in ibid., 348–49.

- Michele Amedei, “Per un’introduzione agli scultori stranieri all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze nell’Ottocento,” in ibid., 235–56, and “Pittori esteri all’Accademia di Belle Arti fra il 1815 e il 1850,” in Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze. Pittura 1784–1915, vol. 1, 283–96.

- The article, “La Scuola di Ornato,” will be included in the volume mentioned in note 3. I thank Susanna Ragionieri for giving me the opportunity to read the article in advance; its insights and information have been fundamental to my understanding of Chini’s role in the didactic renewal at the Accademia.

- “Sviluppare un linguaggio contemporaneo in una fusione fra arti maggiori e arti applicate, intendendo queste ultime non più in senso esclusivamente classico e storicistico, ma quali saperi artigianali legati alla straordinaria varietà del territorio italiano, con l’intenzione manifesta di allargare l’etica del bello inserendola nello sviluppo industriale del tempo.” Ibid.

- “1919. Le aule scolastiche del ‘dopoguerra’ si aprono larghe e luminose. Marini piazza i primi grandi telai. Frequenta il corso di nudo e d’incisione.” Egle Marini, “Nell’ombra serena,” 18. That Marini attended the Corso di nudo is, however, unlikely. In fact, the Scuola libera del nudo (corso di nudo) remained closed at the Academy from 1915 to 1924. It is likely that Egle was referring to the exercises on the nude Marini pursued for the course Plastica d’Ornato, which required the composition of high reliefs with nude protagonists. See, in this regard, one of Egle Marini’s earliest works in Egle Marini 1924–1968, ed. Luana Cappugi (Milan: Electa, 1990), 16.

- See Trentacoste, letter to the Ministry appointing Galileo Chini as professor of Ornato, December 18, 1919, in AABAFi, Fascicoli personali docenti, Chini Galileo, minuta. I thank Susanna Ragionieri for bringing this document to my attention.

- Since his childhood, Marini was “un ragazzo di poche parole, pronto allo scherzo e alla risata. Nel 1917 […] è sereno, meno silenzioso, più assorto.” Egle Marini, “Nell’ombra serena,” 17.

- In the first works he made at the Accademia, Marini “intarsia col colore: sono accostamenti gialli in una testolina d’uccello; meandri vermigli e oro di una corolla; smeraldi e giade su insetti analizzati come gioielli; trasparenze, lievità d’atmosfera; fraseggiatura d’una fiaba interiore.” Ibid., 18.

- Sibilla Panerai, “Le decorazioni di Galileo Chini in Toscana: un itinerario tra neomedievalismo e Jugendstil,” in Galileo Chini e la Toscana, 62–63.

- Susanna Ragionieri, “Natura trasfigurata e mito nella Toscana degli anni Venti e Trenta,” in La Toscana e il Novecento, ed. Francesca Cagianelli and Rossella Campana (Pisa: Pacini, 2001), 169.

- It is interesting that the execution of Marini’s drawing was contemporaneous with the publication of Piero della Francesca (1927) by Roberto Longhi, a pioneering study the great Tuscan painter.

- Fabio Benzi, Galileo Chini. La decorazione del Palazzo Comunale di Montecatini Terme (Florence: Maschietto Editore, 2019).

- Panerai, “Le decorazioni di Galileo Chini in Toscana: un itinerario tra neomedievalismo e Jugendstil,” 61–63. From the end of the nineteenth century, Chini had shown an interest in the Secession’s decorative style.

- As argued by Mario De Micheli, in some of Marini’s early engravings (including L’Estate) “ci si avvede […] una certa suggestione d’ascendenza secessionista, con l’inclinazione ad enfatizzare la forma, e darle rilievo e plasticità.” De Micheli, “L’idea, il segno, l’immagine,” 11.

- At the Scuola d’incisione, the students worked “in libertà con gioia, ma con ostinato rigore […] pieni di fiducia”; “lo Studio [i.e. Scuola] prese subito, secondo le mie precise intenzioni [i.e. Celestini’s], il carattere di un’antica Bottega [sic] anche nel suo carattere esteriore; carattere che da allora [the year in which the Scuola di incisione was founded in 1912] ho sempre voluto fosse gelosamente conservato.” Celestino Celestini, “Notizie sulla Scuola d’incisione dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze,” typescript document, Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze.

- “Cominciai a sognare un’organizzazione in grande stile,” writes Celestini, recounting how the Scuola d’incisione was born. Celestini founded it at the academy in 1912, with the help of the painters Carlo Raffaelli (dates unknown) and Francesco Gioli (1846–1922), on the basis of the work of Giovanni Fattori, another professor of painting: “Nella continuità ideale […] del maestro [Fattori] vedevo anche quella tradizione gloriosa dell’Incisione toscana attraverso i secoli, fino agli ultimi celebri nomi di Raffaello Morghen ed Antonio Perfetti che tra la fine del ‘700 ed i primi dell’800 ebbero ‘bottega’ proprio qui nell’Accademia [of Florence], ed al Fattori stesso. E questa ripresa a Firenze poteva saper di poesia: una curiosa leggenda attribuisce all’orafo fiorentino quattrocentesco Maso Finiguerra per lo meno l’invenzione dell’Arte di stampare l’Incisione su metallo, se non questa addirittura.” Ibid

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato dell’Opera grafica (incisioni e litografie), 1919–1920, no. A4, 25.

- I luoghi di Giovanni Fattori nell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, passato e presente, ed. Giuliana Videtta and Anna Gallo Martucci (Florence: Pagliai, 2008); and Giuliana Videtta, “Giovanni Fattori e l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze,” in Accademia di Belle Arti. Pittura, 179–90.

- See Giovanni Fattori. La poesia del vero, ed. Andrea Baboni (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2008); Giovanni Fattori tra epopea e vero, ed. Giovanni Fattori (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2008); and Fattori, ed. Francesca Dini, Fernando Mazzocca, and Giuliano Matteucci (Venice: Marsilio, 2015).

- See De Lorenzi, “Su alcune sculture di Domenico Trentacoste.”

- Trentacoste’s Derelitta is addressed in detail in a forthcoming article by Giovanna De Lorenzi.

- De Lorenzi, “Su alcune sculture di Domenico Trentacoste,” 197 and 201.

- Ibid., 192.

- Ibid., 198–204; and De Lorenzi, “Firenze, la Francia e le arti figurative fra Ottocento e Novecento.”

- See the message from Marini to Trentacoste held in the Archivio Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Florence, Fondo Trentacoste, racc. 8, ins. 4: “Felicitazioni vivissime auguri – Marino.”

- On the medals by Trentacoste, see Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti. Catalogo generale, vol. 2 (Florence: Sillabe, 2008), 1816–18.

- Prima mostra provinciale d’arte (Pistoia: Arte Stampa, 1928), nos. 192–97, 29–30.

- Renato Fondi, “Marino Marini incisore e scultore,” in Rassegna grafica, nos. 20–21 (1927).

- “Egli [Marino] tende con tenaci sforzi a ritrovare quell’espressione complessa, ingenua e scaltra nello stesso tempo, tipicamente rigida, raffinata e acerba, che distingue il nostro Quattrocento.” Ibid.

- Alberto Giuntoli was enrolled in the Scuola d’Ornato in the same year as Marino and Egle Marini (AABAFi, Alunni, Iscrizioni, 1905–1922, no. 1610).

- Susanna Ragionieri, “Il circolo di Lanza del Vasto,” in Arte del Novecento a Pistoia, ed. Carlo Sisi and George Tatge (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2007), 40–63, and “‘Senza che l’astratto perda purezza, né la vita plenitudine’: il rapporto di Lanza del Vasto con gli artisti toscani alla fine degli anni Venti,” in Lanza del Vasto e le arti visive, ed. Manfredi Lanza (Fasano: Schena, 2007), 22–38. Ragionieri argues that Putto che suona (figure 5) was the inspiration for Solaria’s logo.