“A Nordic Mystery”: Insights into Marino Marini’s Sojourn in Switzerland During World War II

Nicol Maria Mocchi Nicol Maria Mocchi Marino Marini, Issue 5, May 2021https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/marino-marini/

This essay focuses on Marino Marini’s self-imposed retreat to Switzerland, his wife’s native country, in December 1942, to escape the bombings in Milan during World War II. He would return to Milan in the winter of 1945, resuming his professorship at the Brera Accademia di Belle Arti. His Swiss years were particularly fruitful and experimental, but also the darkest and least explored of his career. They influenced his most peculiar artworks (including the Archangels, Miracles, and Pomonas), marked by disproportionate shapes and corroded surfaces, and strongly inspired by the “Nordic mystery” towards which he felt instinctively attracted. Against the backdrop of the dramatic war years, this essay reassesses Marini’s work in the light of a broader emerging Swiss art scene of international artists, museum directors, art collectors, and critics who variously contributed to the widespread knowledge of his oeuvre.

This paper explores Marino Marini’s sojourn in Tenero-Locarno, Switzerland, where he and his Swiss-born wife Mercedes Pedrazzini (1913–2008), better known as Marina, took refuge between the winters of 1942 and 1945. 1 On December 1942 the couple had left Italy to escape the Allied bombing raids on Milan, stopping briefly in Merate and Blevio, on Lake Como. Marini would go on to spend three whole years in Ticino, surrounded by the peaceful Alps. There, one of the most important yet little studied periods of his career unfolded,2 marking a significant turn in his artistic, ideological, and sociopolitical identity.

Once in contact with the cultural environment of central Europe, Marini’s art underwent a radical change, both in style and syntax, which set him apart from the eclectic and culturally conservative tendencies of the prewar period aligned with fascist ideology. The new path led him towards a more dramatic and expressionistic language, characterized by corroded surfaces and disproportionate and mutilated shapes that Marini perceived as imbued with “Nordic mystery” (mistero nordico),3 towards which he felt instinctively attracted. That the North had a significant impact on Marini’s art was also stressed by Gianfranco Contini (1912–1990), the Freiburg-based philologist who in 1944 wrote of “a sort of Nordic experience with a harsher light and a more sour epidermis.” Thus Marini’s Ticino works became instilled with an unprecedented expressiveness, giving them “a well-differentiated aspect in all of his production.”4

Starting from Contini’s statement and relying on a range of archival documents here examined for the first time, this essay aims to reassess Marini’s production of 1943–45 (sculptures, drawings, and engravings) in light of the broader coeval artistic context, both by addressing his relationships with other émigré artists and their reciprocal influence, and by discussing the most significant interpretative keys applied to Marini’s works, especially in the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, which paved the way to the international reception of his art in the postwar years.5 It is worth noting that Marini was not a political refugee, unlike many of his friends and colleagues who were involved in the dramatic exodus following the armistice of September 8, 1943, when soldiers in disarray, Jews, Fascists, anti-fascists, and civilians fled the threat of the Italian peninsula’s military occupation by Nazi forces and their supporters from the puppet Republic of Salò.6

Yet things were by no means easy for Marini. His house in Milan and studio at the Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche, in nearby Monza, where he had taught sculpture from 1930 until 1940, were bombed and completely destroyed after he left.7 The war interrupted his new job as a sculpture teacher at the Accademia di Belle Arti at Brera, begun in October 1941. And last but not least, with Marini’s departure from Italy, his works, which had gained public recognition at government-sponsored exhibitions (the Grand Prize for Sculpture at the II Quadriennale of Rome in 1935; at the 1937 Paris Exposition Universelle), lost visibility as the esteem he had earned over the years weakened. Restrictive measures introduced by the Federal Foreigners Police (Eidgenössische Fremdenpolizei) in Bern hindered or fully prevented competition from non-Swiss artists.8 Having entered Swiss territory as a foreigner,9 Marini was forbidden from practicing any profession and could not sell artworks. His wealthy in-laws, who resided in Locarno, offered their help by letting the couple stay at an old family home in nearby Tenero – the still-existing Castèl.10 Meanwhile a studio immersed in a spacious garden was generously loaned out to him by a well-off elderly Swiss-American woman named Juliet Brown-Melms (1869–1943), whose portrait Marini completed shortly before her death, possibly to convey his gratitude.

In several interviews given after World War II, Marini maintained that in the silence and stillness of Tenero he had found “a great calmness” (una grande calma),11 had “thought about angels” (pensavo agli angeli), and had “become pure and listened to nothing but music” (ero diventato puro e non sentivo che musica).12 His descriptions suggest a new joy and expressive freedom, despite the tragedy of the moment. His experience was like a state of grace, from which arose, in his own words, “a series of very Catholic expressions of art” that he described as “very spiritual,” “alive,” “pure,” “thought-through,” and “hypersensitive, of a deeply shattered and deeply sad nature.”13

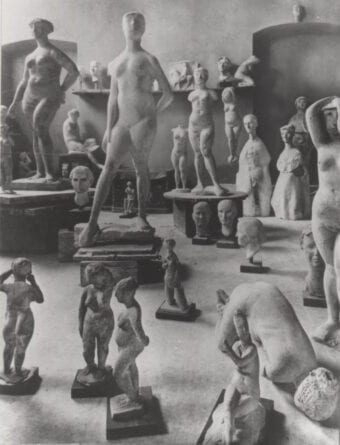

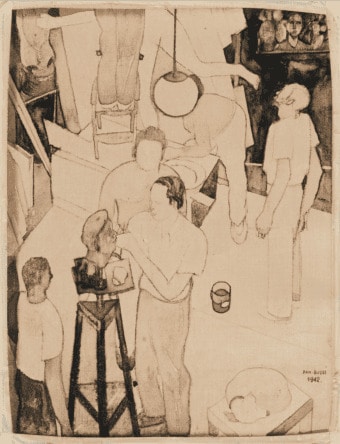

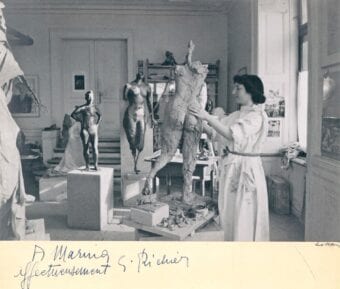

The Tenero studio no longer exists, but was immortalized in photographs, paintings, and drawings by artists who visited Marini between 1943 and 1945, documenting the creative fervor of his Ticino period. The most fascinating photographs are those taken by the Viennese sculptor Fritz Wotruba (1907–1975) (figure 1), who emigrated to Switzerland in 1939, following the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany. There are also the more intimate shots of photographer Christian Staub (1918–2004), which show Marini working on one of his medium-sized Bathers. Photographs by the Zurich gallery owner Bettina and Pietro Pancaldi from Ascona, focus on the atelier but also provide glimpses into its “paradisiacal”14 view of the garden. At the Kunst Museum Winterthur, a long-forgotten painting by local late-Impressionist Gustav Weiss (1886–1973) (figure 2) and preparatory studies portray Marini at three different moments of his work.

Themes

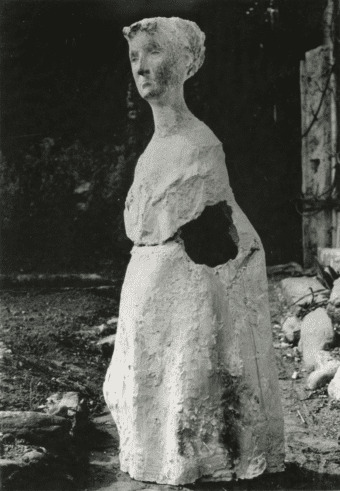

During the war, Marini concentrated on a limited number of themes: portraits, which earned him a substantial living and fame among the bourgeoisie and local aristocracy (his clients included the Tateli-Grandjeans, from Lausanne (figure 3); Werner Amsler, of Schaffhausen; Hedy Hahnloser, in Winterthur; and Karl von Schumacher and the brothers Ulrich and Manuel Gasser, of Zurich); small-scale equestrian figures; and above all, female nudes. His favorite subject from the early 1930s, Marini’s female nudes included Pomonas (figures of fertility inspired by Etruscan art), Graces, and Bathers. New themes imbued with a northern, neo-Gothic spirit also appeared in Switzerland: Miracolo (Miracle, 1943, figure 4; Arcangelo (Archangel, 1943; a portrait of Marina’s brother-in-law Gianni), with its female counterpart Arcangela (Archangel, 1943, figure 5; a portrait of Marina); and Giocoliere (Juggler, 1944), whose stylistic features (elongated shapes, pathetic glances, and expressionistic emphasis) were to characterize his artistic research for years to come.

Museo del Novecento, Marino Marini Collection, Milan. © Comune di Milano.

The sculptor favored materials such as terracotta and gesso, motivated by at least three intertwining reasons. The first was economic. Speaking of the difficulty of transporting works to a 1944 group exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel, Marina recalled that “bronze castings had a prohibitive price and we could not afford it.”15 The second reason, which she also mentioned, was more sociopolitical: “At that time almost nobody bought sculptures.”16 Because Marini as an Italian citizen was prohibited from selling his works, it was pointless and unaffordable to cast them in bronze. According to the journalist Urs Schwarz, foreign editor of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung from 1942 on, Marini had been expressly “forbidden by the police to have any of his works cast in bronze and had to sell plaster casts clandestinely in order to make a living.”17 Of course, Marini tried to circumvent this ban. An exhibition featuring his works was scheduled to take place in the summer of 1945 at the Kunsthalle Bern. In May of that year, Marini wrote to the director Max Huggler (1903–1994), asking him to intercede with the Swiss authorities “exceptionally to obtain permission to make sales during the period of this exhibition,” because “throughout the war I had large expenses, I am on the eve of returning to Italy and I would be happy to make some sales.”18

The third reason for Marini’s use of widely available and inexpensive materials such as terracotta and gesso was essentially technical and stylistic. They allowed him to experiment with new sculptural means and forms, enhancing the expressive, pictorial values of his surfaces by scoring and scratching into them with various tools such as mallets, spatulas, chisels, and knives – Contini notably called him “a poet of surfaces: everything else is inessential to him.”19 In Basel’s National-Zeitung, Marini’s artisanship was more accurately described as follows: “Marini casts and molds at the same time, he reworks the raw cast with sculptors’ tools and color, and proceeds in the manner of the plasterer. He breathes life into the opaque, neutral white mass, obtaining an immediate and tension-filled effect, which strikes the viewer.”20

Relationships

The documentation discussed thus far confirms Marini’s contact with a broader European art scene. Letters, artworks, and photographs demonstrate that Marini did build relationships with the Locarno artistic community, which was then animated by the eclectic personality of Remo Rossi (1909–1982) (figure 6). However, he was much more receptive to and intellectually in tune with the community of exiled artists who at that time were located in the liveliest part of German-speaking Switzerland, in particular Zurich and Basel. Marina’s fluency in German, French, and English undoubtedly facilitated these multicultural interactions. In addition to Wotruba (figure 7), “a nice, strong man, an incredible worker, always struggling with huge boulders of stone,” who lived in nearby Zug, “where we were guests several times,”21 Marini spent most of his time with friends and colleagues he had befriended during his trips to Paris in the 1930s. Among them, special mention goes to Germaine Richier (1902–1959)22 (figure 8) and her husband Otto Charles Bänninger (1897–1973), who had taken refuge in Zurich at the outbreak of the war. In Zurich, where Marini’s “artistic activity”23 mainly took place by his own admission, he also came into contact with renowned local artists such as Hermann Hubacher (1885–1976); Robert Müller (1920–2003), who was Richier’s apprentice; and Hermann Haller (1880–1950), “frequent guest [at Tenero] and a great admirer of Marino as a man and as a sculptor.”24 In Basel, Marini often met up with sculptor Hugo Weber (1918–1971), who was a friend of Hans Arp (1887–1966) as well as Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966),25 and would later teach at the Institute of Design in Chicago (also known as the “New Bauhaus”).

According to Marin himself, he created some of his most important sculptures in Basel: the gessoes Miracolo (1943); Arcangelo (1943); and L’impiccato (Hanged Man, 1944).26 Perhaps they were made in Weber’s studio, where he certainly printed a number of drypoints (artist’s proofs, or numbered editions of six and twelve copies) of female nudes standing, sitting, and lying; of horses; and of riders on horses.27 About thirty additional black-and-white lithographs depicting the same subjects were realized between 1943 and 1945 at the Stamperia Salvioni, in Bellinzona, and at the printing house J. C. Müller, in Zurich.28

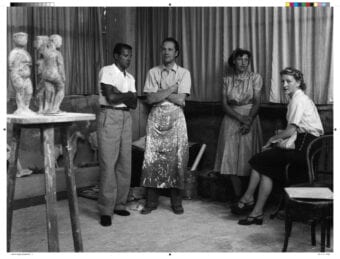

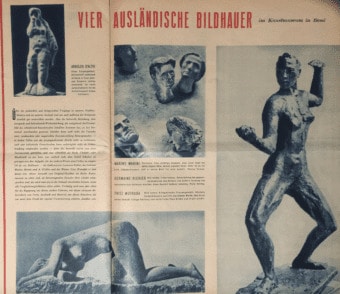

In a black-and-white photograph (figure 9) taken by the art critic Maria Netter (1917–1982) some of these protagonists pose with the Marinis, including Georg Schmidt (1896–1965), director of the Kunstmuseum Basel, Germaine Richier, and the art dealer Christoph Bernoulli (1897–1981); behind them, in the middle of the photograph, is Hugo Weber, while Robert Müller sits in the front row. The occasion for this picture was the aforementioned group exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel in the autumn of 1944, conceived by the journalist Manuel Gasser (1909-1979; feuilleton editor and cofounder of Die Weltwoche) and curated by Schmidt.29 They aimed to repopulate the museum space with sculptures made in Switzerland by four “foreign” artists: Marini, Richier, Wotruba, and Arnold D’Altri (1904–1980, born in Italy but based in Zurich since 1905). Schmidt’s intent was to spotlight four artists working in a spirit of reciprocal exchange both in themes and styles; although they did not constitute a group per se, they were indirectly bound together by the “mutual need to communicate” between “people with the same roots, who are in a part of Europe untouched by the war.”30

Thirty-one artworks by Marini were set up in the famous Böcklin Room, covered in gray velvet, and smaller rooms, and “stood out from the background, creating an effect of rare beauty,”31 as Marina would proudly remember (figures 10 and 11). The sculptures were displayed with drawings, including three of Marini’s Pomonas of 1943–44, Miracolo (1943), Susanna (1943), the terracotta Quadriga (1943; which was subsequently donated to the museum), Arcangelo (1943; later purchased by Bernoulli), and about ten of his “psychological” gesso portraits. Wotruba’s work occupied an entire room, with nine of his best limestone sculptures, from the baroque Torso (1928) to the more severe and linear Liegender (Lying figure, 1943), Denkmal eines Jünglings (Memorial to a young boy, 1942–43), and Allegorische Frauengestalt (Allegoric female figure, 1944), in addition to several drawings. Richier exhibited an important series of bronzes, including Juin 1940 (June 1940, 1940), L’Escrimeuse (Fencer, 1943), La Grosse (1942), and the gessoes Crapaud (Toad, 1940) and Ondine (1944). Arnold D’Altri contributed his renowned Torsos (1937-42) and some of his latest works (figure 12).

Thanks to the efforts of director Max Huggler, with some assistance from Wotruba, the exhibition traveled to the Kunsthalle Bern, where it was presented over the spring and summer of 1945 in a new, thoroughly revised form (it did not include D’Altri).32 In Bern, Marini exhibited sixteen terracotta and gesso works completed between 1942 and 1945 and the bronze Monaca (Nun, 1928). In the exhibition rooms, these works were in dialogue with monumental sculptures by Wotruba and others by Richier. In an additional room, a group of small sculptures and several drawings and watercolors were displayed; they were all by international sculptors, mostly French, including Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), Aristide Maillol (1861–1944), and Charles Despiau (1874–1946), and were lent by major local collectors such as Willi Raeber (1897–1976), Georges Moos (1912-1984), and Werner Bär (1899-1960). On the evening of June 14, a lecture was delivered in French at the exhibition by Marini’s close friend, collector, and biographer, Lamberto Vitali (1896–1992), which focused on Marini and Italian sculpture. Little is known today about this talk; but there is reason to believe that it offered a comprehensive analysis of Marini’s artistic production up until that point. It is worth remembering that Vitali was then interned in a military camp at Mürren, in the Bernese Oberland, where he gave lectures on art history to inmates in a university headed by the anarcho-syndicalist Agostino Lanzillo (1886–1952).

Apart from the Basel and Bern shows, exhibitions of Marini’s Swiss works were mainly circulated among art galleries and private collections in Germanophone Switzerland,33 reflecting a growing interest, both artistic and commercial, in his art, which was overwhelmingly well received by prominent local critics. In the autumn of 1945, for example, the Jewish-French art merchant Toni Aktuaryus (1893–1946) hosted an exhibition at his Zurich gallery devoted to “three Italian artists residing in Switzerland”: Marini, D’Altri, and Guido Gonzato.34 Precious information about the exhibiting artists can be gathered through the illustrated essays published in the gallery’s monthly journal.35

The Galerie d’Art Moderne in Basel, founded and directed by Marie-Suzanne Feigel (1916–2006), a close friend of Schmidt, also decided to bet on Marini, organizing two shows. The first, a solo, took place in the autumn of 1945 and featured several sculptures, including portraits, Bathers, Venuses, and bas-reliefs with horses, in addition to sketches and drawings. It was introduced by a concert with music by Igor Stravinsky and Claude Debussy, and by an inaugural speech given by Marini’s friend Hugo Weber.36 The second, a collective show, followed the next year and focused on drawings alone.37 In the same period, one of Marini’s 1943 drawings of horses, then owned by Bernoulli, was included in an exhibition of artworks from local private collections that took place at the Kunsthalle Basel, another of the city’s most prominent cultural institutions.38

It is hard to trace today all the exhibition and commercial channels of the many drawings and sketches realized by Marini in his Ticino period, which had, for obvious reasons, more widespread visibility than his sculptures. Several of these drawings were donated by the artist to friends and collectors. Some works were believed to be lost have reappeared on the market since the war. Marina, for instance, noted the mysterious disappearance of several sketches on pink sheets that her husband had forgotten on the desk of the gallery owner Ulrich Gasser, Manuel’s brother, in Zurich: “The next day he [Marini] went to pick them up, but they had disappeared.”39 From their encounters in Basel, Marie-Susanne Feigel remembered how, “when he [Marini] was sitting in the Restaurant Kunsthalle, he drew on the paper tablecloth that was on the table. The drawings were then distributed. This is how we got a collection of real Marino Marinis.”40 Having sensed the possibility of earning some income in a moment of undeniable economic difficulties, Marini acted on several fronts to exhibit his graphic works and possibly sell them. Hedy Hahnloser bought a folder containing ten drawings for a thousand francs41 during one of his visit to the bourgeois villa at Winterthur, which notably hosted French Impressionist and post-Impressionist art. Between 1944 and 1945, the exhibition committee of the Kunsthaus Zürich, chaired by director Wilhelm Wartmann (1882-1970), entered into some negotiations with Marini in the attempt to acquire for the museum or to exhibit a group of drawings by the sculptor and other artists.42 But these initiatives did not go through due to organizational and economic issues, or other wartime disruptions.

It is worth noting how Marini’s works were thoroughly discussed, securing their place in the artistic debate of the time, in particular in German-speaking parts of Switzerland, where they were exhibited and appreciated, and would circulate widely. In discussing the unfinished aspect of his work – its intensely abraded surfaces and the chromatic emphasis on plastic details – critics have generally focused on the two apparently contradictory aspects of humor and tragedy. On the one hand, Marini’s female nudes and penetrating portraits were regarded as imbued with “sculptural humor,”43 “playfulness,”44 “burlesque” (with reference to Susanna, 1943),45 and “mockery.”46 On the other hand, his Archangels and Miracles were interpreted in a more dramatic way – as “almost painfully fragmented,”47 “‘colossi with feet of clay’ […] stigma of the destructive times in which we live.”48 Their pathetic yet solemn postures and heads, mirrored in the same years in the imposing sculptures of Marini’s friend Wotruba, brought to critics’ minds “the ‘bombed,’ homeless, tortured, in short, victims.”49 Both Lamberto Vitali and the poet-painter Filippo de Pisis (1896–1956) had already detected a slight tendency towards humor, caricature, exaggeration, and irony in some of Marini’s portraits of the late 1930s.50

North of the Alps, however, the dominant interpretation of his most recent works attributed a more intimate, existential, and therefore anti-classical and anti-heroical meaning to these same qualities, which were understood as a resistance (Widerstand) to fascist ideology and also as a reaction to the tragedy of the war.51 This humanistic-existential meaning, increasingly ascribed to Marini’s work of the 1940s, significantly contributed to his subsequent American success. His equestrian figures were seen by James Thrall Soby and Alfred Barr, Jr. – the curators of the great Twentieth-Century Italian Art exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1949 – as symbols of an “unforgettable humanism” inspired by or linked to “the memory of peasants fleeing the bombings.”52

Although there is no evidence of what Marini’s political ideas were at the time, he may have had an ideological shift in the mid-1940s – from a conservative, if not reactionary, position to a more progressive stance. This may be connected to his closeness to anti-fascist circles in Lugano, Zurich, Basel, and Bern. In addition, a number of his friends and acquaintances were directly involved in the Italian resistance movement. Among them, it is worth mentioning Gianfranco Contini, who joined the short-lived Italian partisan Republic dell’Ossola in late 1944, created in the Piedmont region bordering Swiss territory. A still unexplored and yet key trace of Marini’s potential shift can be found in the pages of the refugee journal Über die Grenzen. Von Flüchtlingen – für Flüchtlinge [Over Borders. By Refugees — For Refugees], edited by the German communist Michael Tschesno-Hell (1902–1980) from the winter of 1944 to that of 1945.53 In the seventh issue, in May 1945, Marini and Wotruba were announced, among others, as the next contributors to the journal’s supplement Malerei und Plastik (Painting and sculpture); this plan, however, went unfulfilled. Their names were eventually juxtaposed when a review of Wotruba’s pamphlet Überlegungen. Gedanken zur Kunst [Considerations. Thoughts On Art], published in Zurich by Verlag Oprecht in 1945, appeared in the June issue, illustrated by Marini’s classically-rooted, and yet highly powerful bas-relief Le tre Grazie (The three graces, 1943, figure 13).54

From a purely stylistic perspective, Marini’s elongated, disproportionate, and often mutilated shapes, enhanced by strongly contrasting light and shadow, overturn the reassuring stillness and pre-classical naïveté of his prewar works. They have mainly been read in relation to Auguste Rodin, a model, together with his distant ancestor Donatello, that Marini deeply reevaluated during his years of forced retreat55 (not unlike those émigré artists who boasted a Parisian pedigree, such as Richier and Bänninger).

Art produced on Swiss and German land before the twentieth century also had a transformative effect on Marini’s poetics. The “nordic” context, in Marini’s words, offered “a very different music from what I could have in Italy,”56 emanating and spreading, adding a sense of mystery that continually resurfaces in his work. All of his new Swiss characters are clearly the result of a dynamic interplay with this “very different music,” from which arises an almost archetypal and powerful essentiality, poised between medieval polychrome wooden statues and the crude expressiveness of Paul Klee’s (1879-1940) angels. Marini’s contorted female nudes seem to descend from the portals of late Gothic cathedrals, as well as from Lucas Cranach’s (1472-1553) paintings; while the Horses and Knights have their roots in the iconographic tradition of the Apocalypse and of the Triumph of Death, spanning from the grotesque visions of Konrad Witz (c. 1400/10-1445/46) (an artist loved by Alberto Giacometti)57 to the hallucinatory galloping horses of Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901).

Within this framework, the mutual emulation and competition with his new circle of friends certainly played a crucial role in shaping Marini’s peculiar language. On the one hand, he treasured the legacy of the Italian Renaissance (Donatello, Masaccio, Michelangelo, Titian). On the other, he was engaging with ways of appropriation, alteration, and the destruction of that legacy as pursued by his fellows artists – from Richier’s monstrous and surreal imagination to the abstract, geometrized shapes of Wotruba, and from the primordial sensuality of Hermann Haller to the anti-naturalistic and fragmented verticality of Giacometti. These shared artistic influences soon evolved into a sophisticated mélange of common shapes, techniques, and themes, such as the life-sized Pomonas (figures 14 and 15), the Bathers, the Venuses, and other female figures in disparate poses (also reminiscent of the little sculptures of Honoré Daumier [1808-1979], Edgar Degas [1834-1917], and Henri Matisse [1869-1954]). Marini’s figures’ classical roots became, by the end of the war, the eternal idiom of a frightened but ever-hopeful humanity.

At the end of the war, Marini returned to Milan and resumed teaching at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera after the Purge Commission (Commissione di Epurazione) cleared his name from any possible implication with the Fascist regime.58 “Upon returning to Milan [in 1946],” he confessed to his twin sister, the poet Egle, “I felt a real, sensual, and sensitive form again.”59 Marini went back to the themes and visual motifs he had begun investigating before retreating to Switzerland: the nude, the horse (with or without a rider), and portraiture. But at the same time, he instantly realized he “was moving towards something more disquieting” (another recurring word here is “tragic”).60 Their precarious and tension-filled balance, their complex web of diagonals, their playing with full and empty spaces: these factors are all surely in dialogue with the works of both Henry Moore and Pablo Picasso, whose groundbreaking Guernica met Marini’s eyes in photographic form every time he went to visit Richier at her atelier in Zurich (see figure 8, where a detail from the mural-sized painting can be glimpsed behind her).61

Marini’s sojourn north of the Alps, albeit brief, was to leave its mark: the equestrian figures and acrobats of Remo Rossi and the Pomone of Giovanni Genucchi (1904–1979) prove that a significant chapter of Marini’s artistic legacy opened up in 1950s Switzerland. It was a chapter that did not always follow closely in his footsteps, but these artists were able to cherish, reinvent, and rework themes and ideas that Marini had put at the center of his oeuvre, especially during his secluded, yet by no means fruitless, time in Switzerland.

Bibliography

Anonymous. “Vier Länder – vier Bildhauer. Maillol, Kolbe, Haller, Marini.” Schweizer Journal / Revue Suisse 8, no. 10 (October 1942).

Barbero, Luca Massimo, ed. Germaine Richier. Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2006. Exhibition catalogue.

Barr, Alfred H., Jr., and Soby, James Thrall, eds. Twentieth-Century Italian Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949. Exhibition catalogue.

Bernasconi, Pino, ed. Almanacco delle Arti 1945 in occasione della Esposizione tenuta nel dicembre ’44 a Lugano. Lugano: Collana di Lugano, 1945.

Boner, Georgette. Die Malerin Juliet Brown. Eine Monographie. Zurich: Werner Classen Verlag, 1992.

Broggini, Renata. Terra d’asilo. I rifugiati italiani in Svizzera 1943–1945. Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino, 1993.

Bruderer-Oswald, Iris. Hugo Weber. Vision in Flux: Ein Pionier des Abstrakten Expressionismus, Wabern-Bern: Benteli Verlag, 1999.

Caramel, Luciano. Foreword to Marino Marini, edited by Efrem Beretta. Ascona: Bettini & Co. Tipo-Offset, 1989. Exhibition catalogue.

Cavadini, Luigi. “Marino in Switzerland.” In Marino Marini, edited by Pierre Casè, 33–43. Milan: Skira, 1999. Exhibition catalogue.

“Confessioni ad Egle. Dialogo fra Marino e la sorella” (1959). In Marino Marini. Pensieri sull’arte: Scritti e interviste, edited by Marina Marini, 19–29. Milan: All’Insegna del Pesce d’Oro, 1998.

Coray, Pieter, ed. Marino Marini ‘Gli anni nel Ticino.’ Sculture, disegni. Lugano: Edizioni Galleria Pieter Coray, 1981. Exhibition catalogue.

C.S. “Vier ausländische Bildhauer im Kunstmuseum Basel.” St. Galler Tagblatt, November 25, 1944.

Da Costa, Valérie. Germaine Richier. Un art entre deux mondes. Paris: Éditions Norma, 2006.

Dufrêne, Thierry. “Giacometti’s Geneva period (1941–45): The birth of a new sculpture.” In Giacometti: Critical Essays, edited by Peter Read and Julia Kelly, 113–128. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2009.

Feigel, Marie-Suzanne. Erinnerung an die Galerie d’Art Moderne, Basel 1945–1993. Basel: Janus-Verlag, 1993.

Gamble, Antje K. “Buying Marino Marini: The American Market for Italian Art after World War II.” In Postwar Italian Art History Today: Untying ‘the Knot,’ edited by Sharon Hecker and Marin R. Sullivan, 155–172. New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2018.

Guastalla, Giorgio and Guido, eds. Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato dell’Opera grafica (Incisioni e litografie) 1919–1980. Pistoia: Fondazione Marino Marini/Livorno: Edizioni Graphis Arte, 1990.

Guzzetti, Francesco. “Expressionisms.” In Marino Marini. Visual Passions: Encounters with Masterworks of Sculpture from the Etruscans to Henry Moore, edited by Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi, 152–71. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2017. Exhibition catalogue.

H.K. [Keller, Heinz]. “Vier ausländische Bildhauer in der Schweiz.” Werk (December 1944).

H.W. [Weber, Hugo]. “Marino Marini.” Die Weltwoche 13, no. 619 (September 21, 1945).

Kersten, Wolfgang. Paul Klee Übermut. Allegorie der künstlerischen Existenz. Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1990.

K.N. [Kuhn, Heinrich]. “Vier ausländische Bildhauer Im Basler Kunstmuseum.” National-Zeitung, December 12, 1944.

Lévêque-Claudet, Camille. “Giacometti, Marini et Richier en Suisse. Abécédaire 1940-1960.” In Giacometti, Marini, Richier. La figure tourmentée, edited by Camille Lévêque-Claudet, 133–43. Milan: 5 Continents, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Marini, Marina. Con Marino. Milan: Bompiani, 1991.

“Marino Marini par Lamberto Vitali.” Galerie und Sammler 13, no. 8 (October 1945): 197–203.

Marino Marini, presentato da Filippo de Pisis. Milan: Edizioni della Conchiglia, 1941.

Marini, Marino. “Sono etrusco.” Confessioni e pensieri sull’arte (1972). Edited by Staffan Nihlén. Pistoia: Via Del Vento Edizioni, 1997.

Meucci, Teresa. “Marino Marini e Curt Valentin. La fortuna dello scultore in America.” Quaderni di scultura contemporanea 8 (2008): 6–21.

M.G. [Gasser, Manuel]. “Quer durch Zürich.” Die Weltwoche 13, no. 621 (October 5, 1945).

Mittenzwei, Werner. Exil in der Schweiz (1978). Leipzig: Verlag Philipp Reclam jun., 1981.

Nozza, Marco. “L’ispirazione al galoppo. Marino Marini racconta l’avventura della sua evoluzione artistica.” L’Europeo 20, no. 35 (August 20, 1964).

Pedrazzini, Alberto. Lo spettro del Castello di Tenero. Dramma in quattro atti (Dal libro delle leggende) Epoca 1600. Locarno: A. Pedrazzini, 1912.

Plastiken: Marino Marini, Germaine Richier, Fritz Wotruba. Gargallo, Laurens, Lipsi, Manolo, Orloff, Zadkine. Zeichnungen: Rodin, Maillol, Despiau. Bern: Kunsthalle Bern, 1945. Exhibition catalogue.

P.S. “Galleria. Marino Marini.” Libera Stampa 34, no. 3 (January 4, 1946).

Ragghianti, Carlo Ludovico, ed. “Incontro con Marino Marini, 3” (January 14, 1971), Critica d’arte 50, no. 7 (October–December 1985): 57–69.

Schmidt, Georg. “Vier ausländische Bildhauer in der Schweiz. Zur Ausstellung im Kunstmuseum Basel.” Die Weltwoche 12, no. 571 (October 20, 1944).

Schwarz, Urs. The Eye of the Hurricane: Switzerland in World War Two. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1980.

Soldini, Simone, ed. Ticino 1940–1945. Arte e cultura di una nuova generazione. Mendrisio: Museo d’Arte Mendrisio, 2001. Exhibition catalogue.

Vingt Sculptures de Marino Marini présentées par Gianfranco Contini. Edited by Pino Bernasconi. Lugano: Collana di Lugano, 1944.

Visconti, Lisio [Vitali, Lamberto]. “Artisti italiani d’oggi. Mari[n]o Marini.” Corriere del Ticino, May 20, 1944.

Vier ausländische Bildhauer in der Schweiz. Arnold d’Altri, Marino Marini, Germaine Richier, Fritz Wotruba. Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel, 1944. Exhibition catalogue.

Vitali, Lamberto. Marino Marini. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli Editore, 1937.

Watkins, Nicholas. “From Fascism to the Bomb: Marino Marini and the Undermining and Destruction of the Classical European Horseman.” In Myths of Europe, edited by Richard Littlejohns and Sara Soncini, 235–46. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007.

Weber, Hugo. “Thinking Back to Alberto Giacometti.” In Alberto Giacometti and America, edited by Tamara S. Evans, 25–30. New York: City University of New York, 1984.

- Marini’s Swiss period is the subject of a wider publication I am currently preparing. I thank the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) and its president, Laura Mattioli, for granting me the opportunity to present some parts of it here. I extend my sincere gratitude to the Fondazione Marino Marini of Pistoia and its president, Paolo Pedrazzini, for funding both my fellowship at CIMA and my one-month research trip to Switzerland. Archival sources referred to in this article are from: Kunstmuseum Basel; Kunsthalle Bern; Kunst Museum Winterthur; Kunsthaus Zürich; Fondazione Remo Rossi, Locarno; Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milan; the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, New York City; Fondazione Marino Marini, Pistoia; Belvedere Wien. I’m grateful to Rainer Baum, Philippe Büttner, Ilaria Filardi, Thomas Huth, Julia Jost, Valter Rosa, Thomas Rosemann, Ludmilla Sala, Gabriele Stöger-Spevak, and Maria Teresa Tosi for allowing me access or granting me permission to quote from unpublished archival materials. Special thanks are due to my dear friend and colleague Claudia Daniotti for her careful reading and invaluable suggestions that helped me significantly improve this essay.

- Essential works devoted to this particular topic are: Marino Marini ‘Gli anni nel Ticino.’ Sculture, disegni, ed. Pieter Coray (Lugano: Edizioni Galleria Pieter Coray, 1981); Luciano Caramel, foreword to Marino Marini, ed. Efrem Beretta (Ascona: Bettini & Co. Tipo-Offset, 1989), n.p.; Luigi Cavadini, “Marino in Switzerland,” in Marino Marini, ed. Pierre Casè (Milan: Skira, 1999), 33–43; Camille Lévêque-Claudet, “Giacometti, Marini et Richier en Suisse. Abécédaire 1940–1960,” in Giacometti, Marini, Richier. La figure tourmentée, ed. Camille Lévêque-Claudet (Milan: 5 Continents, 2014), 133–43; and Francesco Guzzetti, “Expressionisms,” in Marino Marini. Visual Passions: Encounters with Masterworks of Sculpture from the Etruscans to Henry Moore, ed. Barbara Cinelli and Flavio Fergonzi (Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, 2017), 152–71.

- “Confessioni ad Egle. Dialogo fra Marino e la sorella” (1959), in Marino Marini. Pensieri sull’arte: Scritti e interviste, ed. Marina Marini (Milan: All’Insegna del Pesce d’Oro, 1998), 19–29. See especially page 24: “E questo mistero si sviluppa proprio nella parte più nordica della Svizzera: allora esce fuori una specie di accostamento, qualcosa di intimità assolutamente nordica al cento per cento.”

- Vingt Sculptures de Marino Marini présentées par Gianfranco Contini, ed. Pino Bernasconi (Lugano: Collana di Lugano, 1944), vi: “Ses années de Locarno constituent par contre – c’est lui même qui l’avoue – une sorte d’expérience nordique à la lumière plus âpre, aux épidermes plus aigres”; and vii: “Ces documents de la période suisse de l’activité de Marini acquièrent un aspect bien différencié dans l’ensemble de sa production”. All translations, unless otherwise stated, are mine.

- See especially Teresa Meucci, “Marino Marini e Curt Valentin. La fortuna dello scultore in America,” Quaderni di scultura contemporanea 8 (2008): 6–21; and Antje K. Gamble, “Buying Marino Marini: The American Market for Italian Art after World War II,” in Postwar Italian Art History Today: Untying ‘the Knot’, ed. Sharon Hecker and Marin R. Sullivan (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2018), 155–72.

- For further detail, see Renata Broggini, Terra d’asilo. I rifugiati italiani in Svizzera 1943–1945 (Bologna: Società editrice il Mulino, 1993). Among these refugees were Marini’s biographer, friend, and collector Lamberto Vitali (1896–1992) and the writer and Corriere della Sera journalist Filippo Sacchi (1887–1971).

- Concerning their Milanese flat, see Marina Marini’s memoir Con Marino (Milan: Bompiani, 1991, 41): “venni a sapere in Svizzera che era stato distrutto.” Marini, from Milan, wrote to the commissioner of the Accademia di Belle Arti of Brera on February 21, 1946: “Mentre mi trovavo colà [in Svizzera] venni a conoscenza che il mio appartamento di Milano era stato completamente bruciato ad opera di spezzoni incendiari.” Letter available at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera Archive, “Marino Marini” folder, TEA L IV° 9.

- Marini obtained a residency permit in Switzerland “unter der ausdrücklichen Bedingung, dass er keine Erwerbstätigkeit im Sinne der geltenden fremdenpolizeilichen Bestimmungen (Art. 3 der Vollziehungsverordnung zum Bundesgesetz über Aufenthalt & Niederlassung der Ausländer, vom 5. Mai 1933) ausübt.” See Federal Foreigners Police, letter to Georg Schmidt, Bern, November 2, 1944 (Kunstmuseum Basel Archive, folder K 07/07). For an overview of art and literature in exile, and the legal provisions concerning aliens, see the still useful Werner Mittenzwei, Exil in der Schweiz (Leipzig: Verlag Philipp Reclam jun., [1978] 1981).

- Marina, who most likely lost her Swiss citizenship by marrying an Italian citizen (December 14, 1938), recalled the difficulties they encountered in crossing the Swiss border, which were eventually overcome thanks to a Swiss diplomat and friend of her father Paolo Pedrazzini (1889-1956), who arranged their paperwork. See Marina, Con Marino, 24: “Mi vennero trasmessi documenti falsi che richiedevano la nostra presenza per motivi di successione.”

- A mystery surrounded “el Castèl.” See Alberto Pedrazzini’s drama Lo spettro del Castello di Tenero. Dramma in quattro atti (Dal libro delle leggende) Epoca 1600 (Locarno: A. Pedrazzini, 1912).

- Marco Nozza, “L’ispirazione al galoppo. Marino Marini racconta l’avventura della sua evoluzione artistica,” L’Europeo 20, no. 35 (August 20, 1964).

- Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, ed., “Incontro con Marino Marini, 3” (January 14, 1971), Critica d’arte 50, 7 (October–December 1985), 57–69, especially 61.

- Marino Marini, “Sono etrusco.” Confessioni e pensieri sull’arte (1972), ed. Staffan Nihlén (Pistoia: Via Del Vento Edizioni, 1997), 15–24, in particular page 19: “Una serie di espressioni dell’arte molto cattoliche, molto spirituali, molto vive in quel senso lì, molto pure in quel senso. Molto osservate, direi molto ipersensibili, di una natura profonda scossa e profondamente triste.”

- Georgette Boner, Die Malerin Juliet Brown. Eine Monographie (Zurich: Werner Classen Verlag, 1992), 28.

- Marina, Con Marino, 28: “Le fusioni in bronzo avevano un prezzo proibitivo e noi non potevamo permettercele.” The exhibition Vier ausländische Bildhauer in der Schweiz. Arnold d’Altri, Marino Marini, Germaine Richier, Fritz Wotruba, was on view at Kunstmuseum Basel from October 14–November 26, 1944, and extended until December 31 due to unexpected success.

- “In quel periodo quasi nessuno acquistava sculture.” Ibid.

- Urs Schwarz, The Eye of the Hurricane: Switzerland in World War Two (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1980), 219–20.

- Marino Marini, letter to Max Huggler, Tenero, May 26, 1945 (Kunsthalle Bern Archive, folder 2.01.0097): “Je viens vous demande[r] si vous ne pourriez m’accorder une grande faveur, en intervenant auprès des autorités compétentes pour me faire exceptionellement obtenir l’autorisation d’effectuer des ventes pendant la période de cette exposition. Comme vous le comprendrez certaiment, pendant toute la durée de la guerre j’ai eu de gros frais, je suis à la veille de retourner en Italie et je serais heureux de réaliser quelques ventes.”

- Vingt Sculptures de Marino Marini, ivi: “C’est un poète de surfaces: tout le reste lui est inessentiel.”

- K.N. [Heinrich Kuhn], “Vier ausländische Bildhauer Im Basler Kunstmuseum,” National-Zeitung, December 12, 1944: “Marini giesst und modelliert gleichzeitig, überarbeitet den Rohguss mit Bildhauerinstrumenten und Farbe und geht in der Weise des Stukkateurs vor. Er bläst der glanzlosen, neutralen weissen Masse ein Leben ein, von dessen unmittelbarer und spannungsgeladener Wirkung der Beschauer getroffen wird.”

- Marina, Con Marino, 32: “[Wotruba] era un uomo simpatico, forte, un lavoratore incredibile, sempre alle prese con enormi massi di pietra. […] Aveva anche a sua disposizione una casa sulla riva del lago di Zug dove fummo ospiti diverse volte.”

- On Marini’s fruitful relationship with Richier, see Valérie Da Costa, Germaine Richier. Un art entre deux mondes (Paris: Éditions Norma, 2006), especially 31–40; and Luca Massimo Barbero, ed., Germaine Richier (Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2006), 13–29.

- Nozza, “L’ispirazione al galoppo”: “La mia attività artistica si svolse soprattutto a Zurigo, dove incontrai molti amici e colleghi.”

- Marina, Con Marino, 33: “Hermann Haller era molto assiduo e grande ammiratore di Marino uomo e scultore.” Haller and Marini were significantly linked together in an article in a Zurich monthly journal: “Er [Marini] will kein Sentiment wie der Idylliker Kolbe, er zeigt kein Fleisch wie Haller, der optische Genießer, sondern er offenbart sein künstlerisches Sinnen in Idolen, die wie geträumt erscheinen: unberührbare Fernbilder des Lebens.” Anonymous, “Vier Länder – vier Bildhauer. Maillol, Kolbe, Haller, Marini,” Schweizer Journal / Revue Suisse 8, no. 10 (October 1942), illustrated with Marini’s 1936 Maschera (Giovinetta). Marini’s portrait of Hermann Haller (1947, polychrome gesso, 13 ²⁵/₃₂ x 6 ¹⁹/₆₄ x 8 ¹⁷/₆₄ in. 35 x 16 x 21 cm) is now in the collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich.

- See Hugo Weber, “Thinking Back to Alberto Giacometti,” in Alberto Giacometti and America, ed. Tamara S. Evans (New York: City University of New York, 1984), 25–30. Giacometti, who spent four years in Geneva during World War II, was likely not among Marini’s inner circle of friends. See Marina, Con Marino, 32: “Lo incontravamo [Giacometti] sempre a Ginevra: era una persona curiosa, della quale posso dire poco, perché lo vedevamo raramente e sempre di sfuggita.” See also Thierry Dufrêne, “Giacometti’s Geneva period (1941–45): The birth of a new sculpture,” in Giacometti: Critical Essays, ed. Peter Read and Julia Kelly (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing 2009), 113–28.

- See “Confessioni ad Egle,” 24: “Uno dei primi Miracoli – che è la faccia desolata di quel gesso fatto a Basilea – è proprio fatto sotto l’impressione di un paese che ha delle montagne.” See also Marini, “Sono etrusco,” 19: “Ho lì fatto in quel periodo, a Basilea, l’Arcangelo, il Miracolo, l’Impiccato.” And compare them with Weber’s own commentary “Übersicht der Phasen meiner künstlerischen Entwicklung,” from August 1964 (New York City, Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, Hugo Weber Papers, reels 841–45): “Auflockerung durch Besuche Marinis, der zeitweilig mein Atelier benützt. Dort machen wir auch Kaltnadelradierungen und drucken mit wenig Erfolg auf meiner Presse. Einige gute Drucke im Besitz von Marini und mir […] Zahlreiche Porträts (auch Kopf von Marini und Arp).” On this still untraced gesso portrait of Marini, created by Weber around 1944–45 and shown at the Kunstverein Basel in 1945, see also Iris Bruderer-Oswald, Hugo Weber. Vision in Flux: Ein Pionier des Abstrakten Expressionismus (Wabern-Bern: Benteli Verlag, 1999), 19 and 253.

- Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato dell’Opera grafica (Incisioni e Litografie) 1919–1980, ed. Giorgio and Guido Guastalla (Pistoia: Fondazione Marino Marini; Livorno: Edizioni Graphis Arte, 1990), 200–01, cat. nos. A11–A23.

- Ibid., 231–34, cat. nos. L1–L23 and L24–L30. Much of this material is now dispersed or untraced, with the exception of a few examples that have recently resurfaced on the market.

- In a letter to Georg Schmidt, Zurich, February 26, 1944, accompanied by eighty-four photographs, Manuel Gasser suggests including artworks by, among others, Marino Marini, Fritz Wotruba, Balthus, and Arnold D’Altri. See also Schmidt’s response, Basel, March 7, 1944: “Besten Dank für die sehr interessante Kollektion. Mir unbekannt war einzig D’Altri. […] Geistiger, humaner Marini – und auch er ein wirklicher Plastiker” (Kunstmuseum Basel Archive, folder K 08/03).

- Marina, Con Marino, 31. She is quoting Marini’s words, although chiefly referring to Richier: “Il nostro fu un bisogno reciproco di comunicare di due persone con le stesse radici, che si trovano in una parte d’Europa non invasa dalla guerra.” Marini was until then mainly known to the Basel audience as a “Novecento” sculptor. See Januar-Ausstellung Moderne Italiener, organized by the Geneva-based Alberto Sartoris, Kunsthalle Basel, January 5–February 2, 1930, cat. nos. 145 (La Borghese [The Bourgeois, 1929], fr. 950), and 146 (Testa di giovane donna [Head of a Young Woman, n.d.], fr. 550).

- Marina, Con Marino, 28: “I gessi dipinti risaltavano sullo sfondo creando un effetto di rara bellezza.”

- Plastiken: Marino Marini, Germaine Richier, Fritz Wotruba. Gargallo, Laurens, Lipsi, Manolo, Orloff, Zadkine. Zeichnungen: Rodin, Maillol, Despiau, Kunsthalle Bern, June 9–July 8, 1945. Exhibition catalogue foreword by A.R. [Arnold Rüdlinger]: “Die Kollektion Marinis wurde vollständig neu zusammengestellt unter Verzicht auf fast sämtliche in Basel schon gezeigten Werke.” On the exhibition’s planning, purpose, and organization, see Kunsthalle Bern Archive, folder 2.01.0097.

- One exception is offered by a still mysterious exhibition held in Lugano in December 1944 with paintings by Ticino artists and three Marini sculptures. See Almanacco delle Arti 1945 in occasione della Esposizione tenuta nel dicembre ’44 a Lugano ed. Pino Bernasconi (Lugano: Collana di Lugano, 1945). It is further discussed in Ticino 1940–1945. Arte e cultura di una nuova generazione, ed. Simone Soldini (Mendrisio: Museo d’Arte Mendrisio, 2001).

- Ausstellung drei in der Schweiz lebender Italiener, Galerie Aktuaryus, Zurich, September 26–October 17, 1945.

- Galerie und Sammler 13, no. 8 (October 1945), in particular “Marino Marini par Lamberto Vitali,” 197–203, illustrated by the high-relief Cavaliere (Rider, 1943–44), and two more works, Testa di donna (Portrait of Mme Baumann [Anna Baumann-Kienast], 1944) and Cavaliere (1945).

- Marino Marini, Galerie d’Art Moderne, Basel, September 9–October 5, 1945. In presenting Marini’s art, H.W. [Hugo Weber] stressed the “warme Sensibilität und plastische Gefülltheit, gespiesen von einem menschlich-dramatischen Grundgefühl” (“Marino Marini,” Die Weltwoche 13, no. 619 [September 21, 1945]: 5, illustrated by Lamberto Vitali’s portrait). Weber, who moved to the United States in 1946, introduced Marini’s crucial show at the Buchholz Gallery, New York, directed by Curt Valentin, February 14–March 11, 1950. On this, see also by Bruderer-Oswald, Hugo Weber, 262, note 16 (I thank her for sharing this information with me).

- Ausstellung von Zeichnungen, Temperablättern und Graphic von Braque, Derain, Kandinsky, Klee, Klimt, Kirchner, Magnelli, Marini, Picasso, Rouault, Toulouse-Lautrec etc.. Galerie d’Art Moderne, Basel, May 4-[?] 1946. On Feigel’s contacts with Marini, see her autobiography Erinnerung an die Galerie d’Art Moderne, Basel 1945–1993 (Basel: Janus-Verlag, 1993), especially 23–29.

- Ausländische Kunstwerke des 20. Jahrhunderts aus Basler Privatbesitz, Kunsthalle Basel, September 1–October 7, 1945, cat. no. 124 (Pferdestudie [Study of a Horse], 1943). As stated in the catalogue (page 4), this exhibition focused almost exclusively on figurative artworks – “die dem Naturalismus entweder offensichtlich oder mindestens noch lose verpflichtet sind” – and avoided works closely related to Constructivist or Surrealist art.

- Marina, Con Marino, 31: “[Marino] fece parecchi schizzi e li dimenticò. Il giorno dopo passò per riprenderli, ma erano scomparsi. Recentemente alcuni di questi fogli sono stati messi all’asta da Kornfeld [Galerie Kornfeld] a Berna ed acquistati da nostri amici per un prezzo molto elevato.”

- Feigel, Erinnerung an die Galerie d’Art Moderne, 24: “Wenn er [Marini] im Restaurant Kunsthalle sass, zeichnete er aufs Papiertischtuch, das auf dem Tisch lag. Die Zeichnungen wurden dann verteilt. So kamen wir zu einer Sammlung von echten Marino Marinis.”

- Marina, Con Marino, 34: “[Marino] fece ritorno con una cartella contenente dieci disegni. La nostra ospite [Madame Hahnloser] s’entusiasmò e li volle tutti. […] Diede mille franchi, a noi parve moltissimo.”

- Wilhelm Wartmann, letter to Marino Marini, Zurich, March 12, 1946: “Im Jahre 1944 standen wir im Briefwechsel wegen einer Ausstellung von Zeichnungen Ihrer Hand im Herbst jenes Jahres. Die Unsicherheit der Zeit hat uns dann zu Änderungen unseres Programmes gezwungen” (Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft-Kunsthaus Zurich Archive, folder 2001/002:082, 418). Marini’s sculpture Bacco (Bacchus, 1935) entered the collections of the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1940 (bought for 20.000 Lire) after being exhibited at the government-sponsored Ausstellung Zeitgenössischer Italienischer Maler und Bildhauer (Mostra di Pittori e Scultori Italiani Contemporanei), Kunsthaus Zürich, November 16, 1940–January 12, 1941.

- Georg Schmidt, “Vier ausländische Bildhauer in der Schweiz. Zur Ausstellung im Kunstmuseum Basel,” Die Weltwoche 12, no. 571 (October 20, 1944), illustrated with Arcangelo (Archangel, 1943): “Humor der Form, Humor des Formens, nicht des Inhalts. Humor als die höchste Form der geistigen Freiheit.” It was precisely the alleged “humor” of Marini’s art that gave rise to controversy. In a letter to Schmidt dated November 15, 1944, the sculptor Louis Léon Weber (1891–1972) – a member of the Gruppe 33, an anti-fascist collective of Swiss artists founded in Basel and promoted by Schmidt himself – accused Marini of being deeply embroiled in Fascist propaganda and of clearly abusing “humor” to cover over an ambiguous incoherency: “Als der Fasc[h]ismus brüchig wurde, verfügte sich Marini in die reich bürgerliche Situation seiner Gattin (einer Luganesin) im Tessin. Sie aber treten für den heute so deplacierten ‘Humor’ dieses Exfasc[h]isten ein” (Kunstmuseum Basel Archive, folder O 40/01).

- K.N. [Heinrich Kuhn], “Vier ausländische Bildhauer Im Basler Kunstmuseum”: “die vitale, spielerische und sprunghafte Art des Marini.”

- M.G. [Manuel Gasser], “Quer durch Zürich,” Die Weltwoche 13, no. 621 (October 5, 1945): “Die Suzanne zeigt, wie weit Marini in den Bereich des Burlesken vorstossen kann, ohne sich gegen die ehernen Gesetze grosser Kunst zu vergehen.”

- C.S., “Vier ausländische Bildhauer im Kunstmuseum Basel,” St. Galler Tagblatt (November 25, 1944), photos by Christian Staub: “Jener Frauenkopf mit dem schmalen, bösen Mund muß sogleich etwas Spöttisches äußern!”

- H.K. [Heinz Keller], “Vier ausländische Bildhauer in der Schweiz,” Werk (December, 1944), illustrated by Marini’s Bacco (1935; acquired by the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1941, see note 42): “Formen […] erscheinen vielfach fast schmerzhaft fragmentiert und werden in der Isolierung noch deutlicher.”

- K.N. [Heinrich Kuhn], “Vier ausländische Bildhauer Im Basler Kunstmuseum”: “‘Kolosse auf tönernen Füssen’ […] Stigma des zerstörten Weltbildes einer Generation und der zerstörerischen Zeit in der wir leben.”

- P.S., “Galleria. Marino Marini,” Libera Stampa 34, no. 3 (January 4, 1946): “Nonostante i titoli di Il miracolo, L’Arcangelo ecc., queste teste potrebbero essere quelle dei ‘bombardati’, dei senza tetto, dei torturati, delle vittime insomma.”

- See Lamberto Vitali, Marino Marini (Milan: Ulrico Hoepli Editore, 1937), 18: “[Marini ritrae] talvolta con dichiarati accenti di humour” and his article (written under the pseudonym Lisio Visconti) “Artisti italiani d’oggi. Mari[n]o Marini,” Corriere del Ticino, May 20, 1944, reprinted in Almanacco delle Arti (1945), 18: “talvolta con humour spietato.” See also Marino Marini, presentato da Filippo de Pisis (Milan: Edizioni della Conchiglia, 1941), n.p., speaking of Lamberto Vitali’s portrait: “è leggermente direi quasi caricaturale.”

- On the connection between art, politics, and humor, see Wolfgang Kersten, Paul Klee Übermut. Allegorie der künstlerischen Existenz (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1990). I thank Marc-Joachim Wasmer for bringing this book to my attention.

- Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and James Thrall Soby, eds., Twentieth-Century Italian Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 33. See also Nicholas Watkins, “From Fascism to the Bomb: Marino Marini and the Undermining and Destruction of the Classical European Horseman,” in Myths of Europe, ed. Richard Littlejohns and Sara Soncini (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007), 235–46.

- For further details on this Swiss-German journal, coedited by literary critic Hans Mayer (1907–2001) and writer Stephan Hermlin (1915–1997), see Mittenzwei, Exil in der Schweiz, 351–62.

- Konrad Farner, “Politische Kunst? Eine Bemerkung zu Fritz Wotrubas ‘Überlegungen,’” Über die Grenzen 8 (June 8, 1945): 10. On this bas-relief, whose bronze cast was displayed in the CIMA exhibition Marino Marini: Arcadian Nudes, see Claudia Daniotti’s in-depth analysis at https://vimeo.com/427858714.

- This issue is further discussed in Guzzetti, “Expressionisms,” 152–71.

- “Confessioni ad Egle,” 21–29, especially page 24: “Queste specie di Alpi, che diventano come canne di organo, danno una musica molto differente da quella che io potevo avere in Italia.”

- Alberto Giacometti, D’après Konrad Witz: Saint Barthélemy (Retable du Miroir du Salut), 1942, pencil on paper, 16 ⁹/₆₄ x 10 ⁵/₈ in. (41 x 27 cm). See Dufrêne, “Giacometti’s Geneva period,” 117–18.

- Marini’s membership in the Fascist Party was a prerequisite for his appointment in 1941 as professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti.

- “Confessioni ad Egle,” 21–29, especially pages 24-25: “Ritornando a Milano […] ho risentito una forma reale, sensuale e sensitiva.”

- Ibid. “Ritornando giù [in Italia] mi sono accorto subito di spostarmi verso una cosa più inquietante.”

- A letter addressed to Marina on September 19, 1942, makes clear Marini’s growing fascination with Picasso’s work: during a trip to Zurich in that summer, Marini had the opportunity to study carefully the newly published first volume of the monumental Pablo Picasso by Christian Zervos (Paris: Éditions Cahiers d’Art, 1942), and became so enthused with its illustrations that he encouraged his friend Willy (possibly Willy Bagnoli) to get a copy. See letter from Willy, Moncucco (Milan), to Marina, Locarno, September 19, 1942, Fondazione Marino Marini, Archive, “Correspondence” folder, 710.