“Chiricos checked”: Metaphysical Art in James Thrall Soby’s Notebooks, Spring 1948

Nicol Maria Mocchi Nicol Maria Mocchi Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

This essay concerns the travel notebooks that James Thrall Soby, Head of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the MoMA, filled out in the spring of 1948 during his trip to Italy, accompanied by the director of the museum collections Alfred H. Barr, Jr. The purpose of this trip was to visit the most significant art collections, both private and public, in order to select contemporary artworks for inclusion in Twentieth-century Italian Art, which would be, after the fall of Fascism, the first major North American exhibition to focus entirely on Italian modern art. Relying on the most recent studies on these newly-discovered notebooks, now preserved in the MoMA Archives, my essay will examine and further discuss a particular, arguably predominant aspect of this precious documentary material, enriched by some sketches. It is the importance given, in the great New York show, to the so-called “Metaphysical School,” and to its key protagonists Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, and Giorgio Morandi, focussing chiefly on Soby’s artistic sensibility and critical acumen in extricating himself from the multifaceted panorama of Italian art collecting of the 1940s.

In the spring of 1948, James Thrall Soby, Head of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, made a trip to Italy with the Director of Collections, Alfred H. Barr, Jr.1 The purpose of the trip was to visit the most significant art collections, both private and public, in order to select contemporary artworks for inclusion in Twentieth-Century Italian Art, which would be, after the fall of Fascism, the first major North American exhibition to focus entirely on Italian modern art.2 This paper concerns the notebooks that Soby filled out during this trip – and in particular the three notebooks that chiefly refer to his stay in Milan and Rome in the month of May, respectively designated as “Milan,” “Milan II–X,” and “Rome” – which give precious insights into Metaphysical art.3

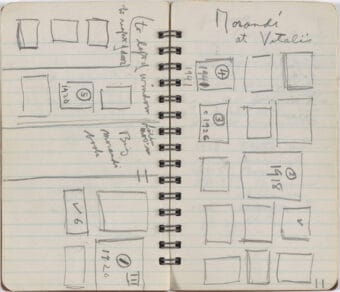

These notebooks, now in the MoMA’s Archives, have been thoroughly examined by Silvia Bignami and Davide Colombo in a conference paper presented at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York in February 2019.4 Developing the suggestion put forward by Elena Cordova in a paper also presented at CIMA four years earlier,5 Bignami and Colombo argued that significant sections of these notebooks were not written by Soby but rather, on account of their handwriting, should be assigned to Barr’s Italian-born wife, Margaret Scolari Barr, who accompanied her husband and Soby almost certainly as interpreter and assistant. It shouldn’t be surprising if we conceive of these notebooks not so much as intimate and personal diaries, but also as working materials, enriched by notes of various kinds, closely related to the exhibition: lists of paintings; annotations concerning meetings with collectors, art critics, scholars, and artists; lists of books; potential lenders’ addresses; comments and critical opinions on the works seen or photographed; and even occasional pencil drawings.6 In the following, I will focus on a particular, arguably predominant aspect of these precious documentary materials, namely, the importance given, in the great North American show, to Metaphysical art as a most influential and celebrated “movement” of twentieth-century Italian art, equaled only by Futurism.

Metaphysical art was presented at MoMA not only according to the interpretative model of the Surrealists (André Breton and his associates), which declared it an artistic creation that originated in the visionary and eclectic mind of Giorgio de Chirico in the golden decade of 1909 to 1919 – an “enigmatic, troubling and deeply poetic art which led eventually to the painting of surrealism.”7 At MoMA it was also introduced – for the first time overseas – as a real “school,” formed by de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, and Giorgio Morandi, all artists who had worked between Ferrara and Bologna from 1916 to 1920, developing an apparently common style of painting.8 Twentieth-Century Italian Art thus replicated the narrative offered the previous year at the Twenty-fourth Venice Biennale (May–September, 1948), in the hall of the “Three Italian Painters from 1910 to 1920: Carrà, de Chirico, Morandi,”9 which Soby and Barr repeatedly visited right after their trip to Milan and Rome, as exhaustively reconstructed by Bignami and Colombo’s paper.

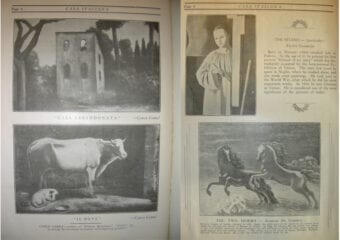

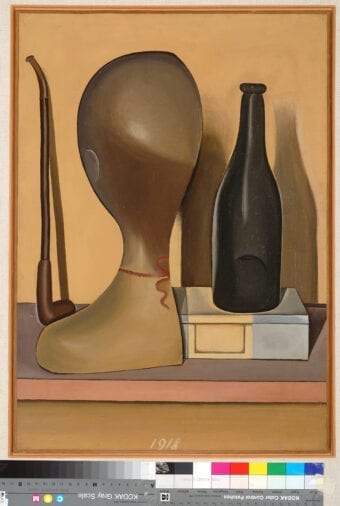

Before 1949, there had been some isolated attempts to make the so-called scuola metafisica known in the U.S. Among them, in 1937 an intimate and still mysterious exhibition of “Metaphysical” works by Carrà, de Chirico, and Morandi, alongside others, was held at the Georgette Passedoit Gallery in New York (figure 1); these works had been brought overseas mainly by Mario Girardon, ex-partner of Mario Broglio’s cultural enterprise Valori plastici,10 a journal-movement that disseminated prominent Italian art of the period to an international audience. In 1939, at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, some other “Metaphysical” masterpieces were displayed in the contemporary art section, including de Chirico’s Ettore e Andromaca (Hector and Andromache, 1917), Carrà’s L’Amante dell’ingegnere (The Engineer’s Lover, 1921), and Morandi’s Natura morta con manichino (Still Life with Mannequin, 1918).11

Twentieth-Century Italian Art was the first exhibition to present – under radically changed political circumstances, and exhaustively – the scuola metafisica as an ideal bridge between the pre-Fascist avant-garde and postwar abstract art. Thanks to its magical and timeless (and therefore depoliticized) atmosphere, and its precious and polished chromaticism, it represented, alongside Futurism, the highest expression of Italian art. A symbol of a new cultural and aesthetic renaissance, it was, as reported in the catalogue, “a movement entirely anti-Futurist in spirit,” and its goal was “to portray an imagery intensified by philosophical reverie.”12

Soby’s notebooks, combined with the exhibition and correspondence files preserved in the archives of MoMA, offer exceptional firsthand documentation of how the show was determined. They reveal the “laboratory” of images and thoughts in which Twentieth-Century Italian Art gradually took shape, and much interesting information can be gathered from their careful analysis. First, the notebooks allow us to focus on choices of cultural policy made by the curators, who aimed to select innovative paintings and sculptures of proven quality, but not so much known among the American public; works which aspired to be both typically Italian and tuned in on an international level. In the notebooks, the most-favored works are marked with an “X.” The curators’ somehow revolutionary aim clearly emerged in contrast to the more reactionary and traditionalist contemporary art exhibitions that had been sponsored overseas during the Fascist period.13

Secondly, these notebooks allow us to grasp Soby and Barr’s artistic and critical sensibility, with which they extricated themselves from the complex panorama of Italian art and collecting after World War II. As the notebooks and many letters and documents relating to the show make clear, Italian collectors – particularly Milanese collectors14 – played an important and, equally, controversial role in the exhibition’s planning: alongside the relatively less-experienced Romeo Toninelli, who was officially the “executive secretary” of Twentieth-Century Italian Art, other influential art critics and collectors (Raffaele Carrieri, Carlo Frua De Angeli, Lamberto Vitali, Cesare Tosi, Antonio Boschi, Emilio Jesi, and Riccardo Jucker – and more) tried to impose their aesthetic taste, and not always successfully.15 A number of documents to be found among the curators’ papers are especially enlightening in this regard, and reveal Soby and Barr’s curatorial strategies and diplomatic efforts. In a letter to Monroe Wheeler, Director of Exhibitions and Publications at MoMA, dated February 9, 1949, Soby lists the professional and personal characteristics of the mainly Milanese collectors, captured as “Dramatis Personae”: Lamberto Vitali is “a man of the greatest integrity. His taste is narrow to the point of fanaticism, i.e. he likes only [Giorgio] Morandi, [Marino] Marini, [Amedeo] Modigliani and [Bruno] Cassinari without reservation. […] I suspect that he will be the most influential figure in the opposition to Toninelli and other newer collector[s] and less professional critics”; Emilio Jesi’s collection (now preserved at the Brera Art Gallery) “is the best in Italy in overall quality, but he has no unreplaceable pictures”; and Carlo Frua De Angeli is “the most powerful business man in Northern Italy, ex-husband of Mary Callery, and a very important collector of both Italian and French pictures. […] We need some of his pictures badly.”16 In a letter written one month after, on March 1, 1949, Soby emphatically specifies to Vitali: “You urge that we not show too many metaphysical paintings by Morandi; we have included only 3 as against 15 pictures either earlier or much later in date than his metaphysical period. You speak of the Rosais of 1920–23 as being the best; all our pictures are of the period 1919–22, and we have put in so many only because they are all small. […] Our list of de Chiricos has always been restricted to metaphysical works, plus a very few pictures of the ‘Roman Villa’ and second Parisian periods; this is in accord with your own ideas.”17

Thirdly, Soby’s notebooks give some practical and anecdotal indications that allow us to identify crucial themes and issues of metaphysical art that the curators paid particular attention to in their various meetings with critics, painters and collectors, such as the theme of the mannequin (most probably because of its prominence in Surrealism),18 or Cubist solutions for the depiction of space and color, to which the two curators felt instinctively attracted.19 Also, for Soby the problem of fake artworks, copies, and replicas of de Chirico works was of high priority.

Last but not least, the many French terms reported in the notebooks document how Soby and Barr often directly related to collectors and gallery owners in the foreign language with which they were most comfortable: Carrà’s painting La casa dell’amore (The House of Love, 1922) is defined as “giottesque”;20 and a small Mario Sironi painting from 1942, observed in the Frua De Angeli collection, is described “avec deux figures.”21

Undoubtedly, the most cited artist is Giorgio de Chirico, “the founder and leading figure” of the scuola metafisica. On de Chirico, Soby aspired to gain the most information and knowledge.22 Soby was a leading connoisseur of Metaphysical art, and intended on this Italian trip to collect material for the second edition of his de Chirico monograph published in 1941, which had attracted the artist’s intense criticism. De Chirico had publicly accused Soby of reproducing two fake paintings, but then retracted this claim, much to Soby’s bewilderment.23

The importance of this artist in the framework of the Italian trip is confirmed by the phrases “Chiricos checked” and “checked for Chirico,” which appear at the start of the Roman and Milanese notebooks. There is almost no page, especially in the latter ones, on which the artist’s name does not appear: sometimes with lists of paintings or drawings, or often combined with technical, stylistic or iconographic indications. On May 1, 1948, Soby had the opportunity to directly confront de Chirico’s brother, Alberto Savinio, and a detailed testimony remains in the notebooks.24 Soby put several questions to his illustrious interlocutor, whose answers would appear both in the 1949 MoMA exhibition catalogue and partially also in his 1955 edition of the de Chirico monograph. Soby’s line of inquiry can be traced back to the two themes that most interested him: the origins of metaphysical art, concerning which he asked for explanations of various iconographic and technical-figurative representations; and the problem of forgeries, copies, and replicas of de Chirico’s work – which had come to obsess Soby. De Chirico’s “fake” artworks were a much debated problem after World War II: the 1948 Venice Biennale and Soby’s monograph, which first arrived in Italy in 1946, consecrated the painter as the most important Italian artist of the twentieth century, and the consequent re-evaluation of his early work offered de Chirico the opportunity to produce backdated copies.25

One of the most sought-after paintings for Twentieth-Century Italian Art, as can be seen in the notebooks, was the masterpiece of the Ferrara period Le muse inquietanti (The Disquieting Muses, 1918), which Soby and Barr saw in Pietro Feroldi’s collection in Brescia,26 and of which until then at least two copies circulated. Notes on a May 14, 1948, meeting with Giorgio Castelfranco, former owner of the painting and de Chirico’s patron for several years, reveals the curators’ anxiety to learn more about the original work and the faithful replica created in 1924 for the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard (previously offered to Breton): “Castelfranco says he gave Breton permission to have a copy made by [de] Chirico of Muses Inquietantes [sic] for which B[reton] paid 5,000 francs or so, c. 1922. But [de] Chirico didn’t go back to Paris until 1924?”27 In a letter dated August 29, 1948, written after his return to the U.S., Soby stressed the urgency of obtaining further information and clarifications on this painting: “Still feel we should have a look again at the second version of the Muses – just to be sure.”28

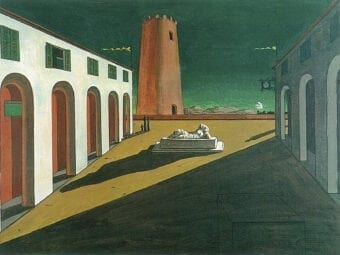

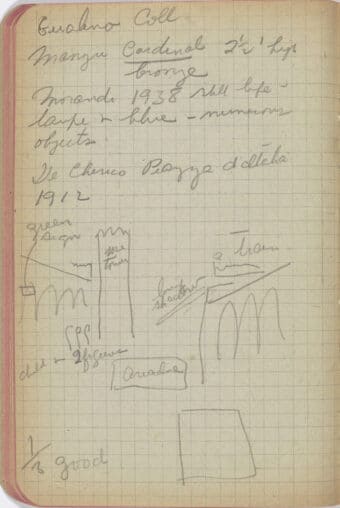

With regards to the problem of fakes, the notebooks confirm the sensitivity and critical acumen of Soby, who on several occasions raised his doubts about the dating or authenticity of de Chirico paintings observed at various collectors’ homes. Two 1915 Piazza d’Italia with Ariadne and Cavour and a 1916 Interno metafisico (Metaphysical Interior), all owned by Frua De Angeli, Soby discarded as “fakes” or executed “really later.”29 Meanwhile, Soby did opt for undisputed masterpieces of the Metaphysical period such as Interno metafisico con grande officina (Metaphysical Interior with Large Building, 1916) and I pesci sacri (Sacred Fish, 1918–19).30 About a Piazza d’Italia (figure 2) seen in the collection of Riccardo Gualino in Rome and dated 1912, and today recognized as a bad replica from the late 1930s, Soby summarized: “green sign / rose tower / a train / long shadow / child & 2 figures / Ariadne / 1/3 good / Chirico white columns at left are very heavily painted. Right section looks ok as does the signature. Rose tower very bad.”31

A similar note of suspicion arises concerning another 1912 Piazza d’Italia, seen in the collection of Franco Marmont in Milan (“medium size – thick paint, fine canvas – smoke & chimney bad”32); about a 1914 Piazza d’Italia with the statue of Cavour, owned by Emilio and Maria Jesi, Soby commented “no doubt says he [Jesi] because he’s had it so long.”33

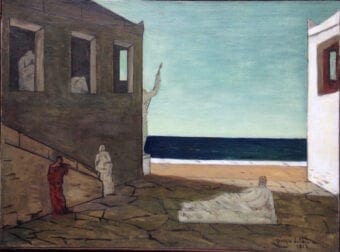

Besides Soby’s scientific rigor, the notebooks reflect the lively pleasure and authentic emotion that he experienced in front of some of the cornerstones of de Chirico’s Metaphysical art, such as Meditazione del mattino (The Morning Meditation, 1912; figure 3), owned by Riccardo Jucker – a picture already known in the U.S. because it was exhibited at the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. Soby’s description dwells on the technical and figurative details: “Dark blue sea – below sea a white strip – ground under strip & light tan. Figure at very left dark red – Room inside window at right dark red.”34 The painting, however, was not loaned to the MoMA exhibition.

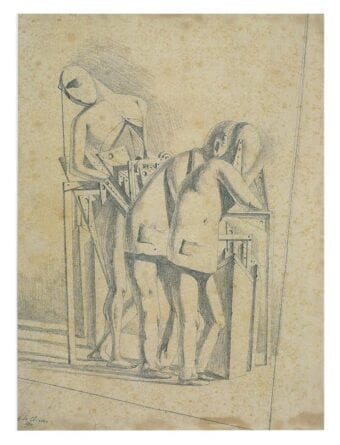

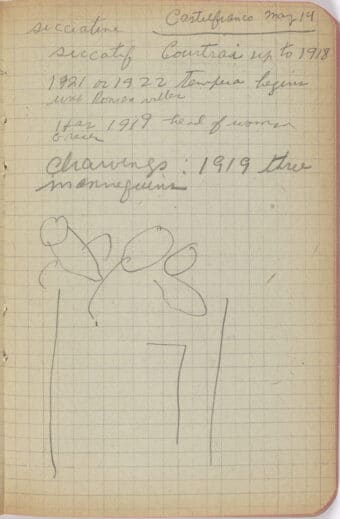

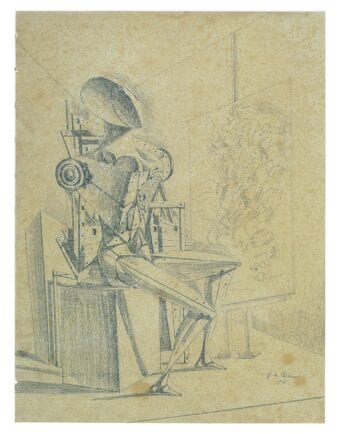

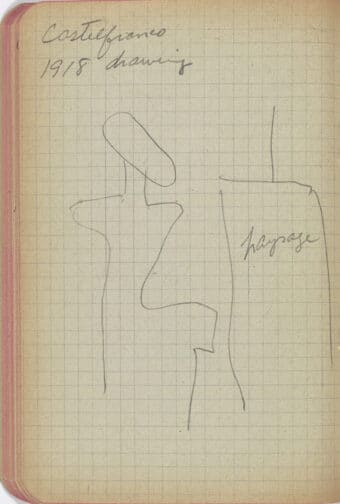

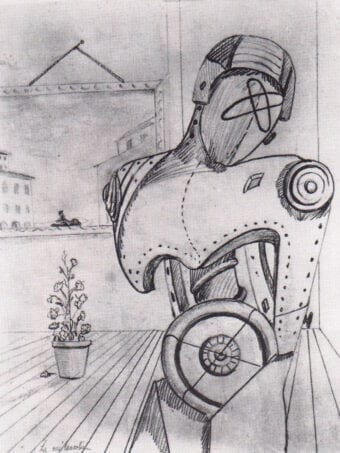

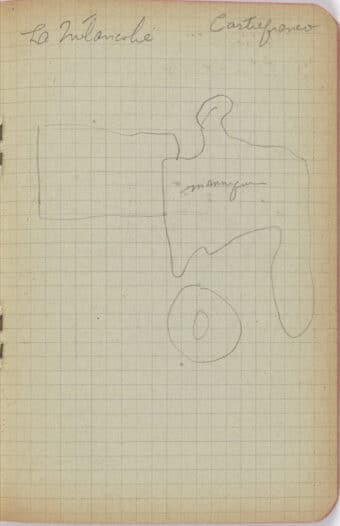

Soby’s excitement at de Chirico’s rich graphic production is evidenced in the notebooks by some rough sketches of Metaphysical drawings with mannequins – all certainly by his hand. Those drawings in Castelfranco’s Roman house especially capture his naive sensibility for the essence of Metaphysical iconography: “drawings: 1919 three mannequins; Castelfranco 1918 drawing – paysage; Castelfranco La Mélancolie – mannequin”35 (figures 4–6). Il manichino pittore (The Mannequin Painter, 1918) was undoubtedly appreciated by Soby for its numerous iconographic references to de Chirico’s painting Il vaticinatore (The Seer, 1914–15), then possessed by Soby himself and eventually selected for the show.

The curators’ visits in Milan to the Boschi and Jesi collections, widely reported in the notebooks almost certainly by Margaret Scolari Barr with precious commentary by Soby, did not, unfortunately, yield any de Chirico loans.

As the notebooks seem to suggest, the few works of the 1920s in Twentieth-Century Italian Art that show a remarkable “return to craft”36 as well as to painting in the classical Italian tradition were probably chosen to replace masterpieces of the golden decade (1909–19) that could not be loaned. Il giorno e la notte (Day and Night, 1926), in the Jucker collection – marked in the notebooks with an “X” beside a question mark – and the Rubensian Ettore e Andromaca (Hector and Andromache, 1924),37 seen in Romeo Toninelli’s collection, were subjects less appreciated by Soby, as is clear in a letter to Barr: “I don’t really think this [Feroldi’s Hector and Andromache] is as good as Frua’s single figure, Troubadour, and anyway, being so incurably purist in these matters, feel the 1915 mannequins are really much better.”38 La partenza del cavaliere errante (The Departure of the Knight Errant, 1923), lent by Adriano Pallini, and the Paesaggio romano (Roman Landscape, 1922), lent by Yvonne Casella, are not remarked upon in Soby’s notebooks; the latter collector was encountered by Barr during his prolonged stay in Rome, when Soby had already moved to Venice, where he was doing a “fantastic labor in the galleries of the Biennale,”39 as reported in a letter dated May 22.

Carlo Carrà, the second member of the scuola metafisica, was, at the time of the exhibition’s planning, an artist mainly known to the American public as an irreverent Futurist of the prewar years, or, alternatively, as a painter of an “idyllic,” deliberately unadorned neo-classicism, as exemplified in his several works of fishermen, athletes, and bathers previously presented at the Pittsburgh’s Carnegie annual shows, and in the pages of Italian-American magazines more aligned with the regime, such as Columbia University’s monthly Bulletin of the Casa Italiana (figure 7).

Barr and Soby had two distinct but complementary purposes with regard to Carrà: to make his pictorial and theoretical contribution to Metaphysical art known abroad; and, at the same time, to confirm his previous connection to Futurism with five works, including, notably, the pioneering Ciò che mi ha detto il tram (The Tram, 1911), seen at the Milanese Circolo delle Arti (chaired by Toninelli), and belonging to the Florentine collector Eugenio Ventura. The notebooks reveal the difficulties encountered by the curators in tracing the few existing Metaphysical artworks of the artist’s 1917 Ferrara period, when he spent a few months with de Chirico in the psychiatric hospital of Villa del Seminario,40 and further developments after his return in Milan. On the whole, their goal was to highlight the specific primitivist and classically-rooted nature of his art, as an alternative to de Chirico’s enigmatic and internationalist eclecticism.

Soby and Barr’s meeting with Carrà took place on May 3, 1948, and was undoubtedly enlightening about his participation in the scuola metafisica. The notebooks also show that the artist was no longer in possession of many of his paintings – neither Metaphysical nor Futurist – though one exception was Donna al balcone (Lady at the Balcony, 1912) – “the only futurist one he has 155 x 135.”41 This section of the notebooks was filled out mainly by Barr’s wife, who, we are much inclined to believe, actively participated in the curators’ decisions.

The five Carrà masterpieces chosen for exhibition at MoMA – out of a total of about fifteen from the artist’s Metaphysical period – partially matched the shortlist of works already displayed at the Venice Biennale and largely admired by Soby and Barr: Il cavaliere occidentale (The Western Knight, 1917), which is a typical example of his being a “dissident futurist,” then owned by Adriano Pallini; Natura morta con squadra (Still Life with Triangle, 1917), lent by Jucker; L’idolo ermafrodito (Hermaphroditic Idol, 1917) and Il gentiluomo ubriaco (Drunken Gentleman, 1916), both from the Frua De Angeli collection; and L’amante dell’ingegnere (The Engineer’s Lover, 1921), which belonged to Feroldi before entering Gianni Mattioli’s collection in May 1949.42 These very last paintings are apparently not mentioned in Soby’s notebooks (it should be noted that some pages are missing or torn), but they are being thoroughly discussed in diverse letters, showing the curators’ appreciation for this particular phase of Carrà’s work. As Soby wrote to Barr on August 29, 1948: “I thought this [The Engineer’s Lover] and the Frua Drunken Gentleman the two best metaphysical Carras we saw in Italy. They seem to me to have a decided quality of their own, and I wish the Museum could have one.”43

In the notebooks, another interesting element that shines through is the curators’ predominant interest in the theme of the mannequin. For example, a work by Carrà identified as “Manichino, 1915, primitive picture in bright colors,” seen at the Galleria Borromini in Milan, was rejected because it was “not really a mannequin.”44

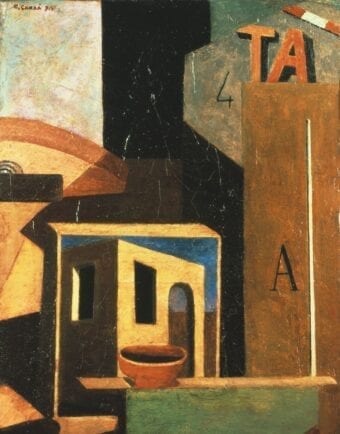

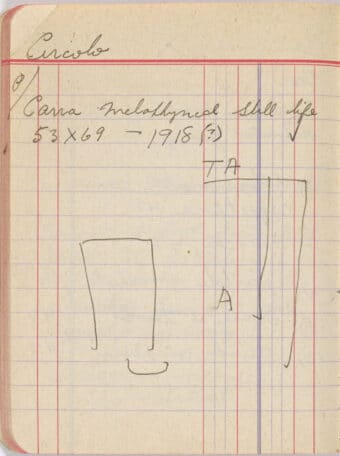

The most representative paintings of Carrà’s artistic kinship with de Chirico are all marked with an “X”: Madre e figlio (Mother and Child, 1917), La camera incantata (The Enchanted Room, 1917), and La casa dell’amore (House of Love, 1922). These they saw in the Jesi collection, and they were not presented at MoMA; the reason for their exclusion, as well as for other relevant artworks, can be probably found in the disagreements with Barr and Soby’s final choices.45 It also remains uncertain why the exhibition did not include Carrà’s Metaphysical still life Composizione TA (Composition TA, 1916–18), that was widely admired in the galleries of the Circolo delle Arti, where it was hanging, as documented in a sketch in Soby’s notebooks (figure 8).46

In the catalogue for Twentieth-Century Italian Art, the third scuola metafisica artist, Giorgio Morandi, is suggested by Soby to have had only “peripheral” involvement compared to de Chirico and Carrà: “Allied with the scuola metafisica, 1918–20, but worked independently.”47 At the same time, his original artistic sensibility is emphasized, devoid of any literary or psychological allusions; it is characterized by a more abstract-geometrical and therefore modern approach, in imitation of the French Purists (for example, Amédée Ozenfant) or the much-beloved Paul Cézanne: “There is, in brief, a lack of supernaturalism and shock in Morandi’s ‘metaphysical’ art as a whole, as compared to de Chirico’s and Carrà’s. In its place there is a lucid plastic equation of which Cézanne, rather more than Giotto or Nietzsche, is the guiding star.”48

The notebooks convey a taste, on the part of the curators, for the “discovery” of Morandi’s masterpieces, which were still little known to the American public. Only during their 1948 Italian trip, in contact with the rich environments of Milanese and Roman collectors, did the two curators begin to appreciate “the authenticity and value of the subtle, poetic, pained Morandian art,”49 increasingly admiring him as much more than a limited and repetitive bottle painter – as had happened in the narrow vision of the previous twenty years.50 Now recognizing him as a premier Italian artist, Morandi was “a man intent on exploring subtle equations of forms, placing and atmospheric effects.”51 The curators’ authentic fascination with Morandi’s artwork is evident also in Barr’s travel notebooks, which depict the picturesque accrochage of paintings admired in Lamberto Vitali’s house (figure 9).52

More than half of the thirteen works by Morandi exhibited at MoMA were intended to illustrate his closeness to Metaphysical art – understood here in a broad sense – in their endlessly varied arrangements of bottles, pans, and jars. Soby and Barr selected examples such as: a 1916 still life bought directly from the artist by MoMA at the close of the 1948 Venice Biennale, at which Morandi won the first prize for painting; a Natura morta con bottiglie e fruttiera (Still Life with Bottles and Fruit Bowl, 1916) “inspired by the Picasso still life rose blue – 1933 – contain watering & Etruscan Vase,”53 as reported in the notebooks, and, to Soby’s taste, “the best of F[eroldi]’s Morandis, but I think there are better ones elsewhere, and we now already have a picture of this year – 1916”;54 two 1918 Metaphysical still lifes from the Jucker collection, both marked with an “X” (Still Life with a Mannequin; Still Life with Box and Ball); a 1919 still life Oggetti (Objects, 1919) possessed by the art historian and academic Roberto Longhi, in Florence; and Natura morta nera (Still Life with Black Objects, 1920), lent by Carlo Cardazzo, who ran the Galleria del Cavallino in Venice.

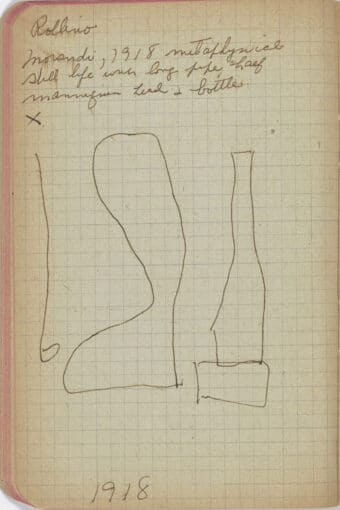

Beyond those early works and several other etchings, the curators selected at least four works to illustrate the post-Metaphysical Morandi they had recently discovered. Characterized by a tonal, sensuously pictorial texture that was “atmospheric” in effect – as described by Soby in the notebooks – these paintings provided opportunity to interpret his art in an existentialist and romantic key. Marmont lent a sophisticated, elaborately crowded “blue” still life from 1937, while the Roman collector Pietro Rollino lent a 1939 still life and a 1940s landscape. At Rollino’s richly furnished apartment, the curators admired more paintings, as recorded in the notebooks, including a “Morandi, 1918 metaphysical still life with long pipe, half mannequin head & bottle X,” referring to the marvelous still life of 1918 now at the Fondazione Magnani-Rocca (Mamiano di Treversetolo, Parma; figure 10); a snow-covered landscape of 1913; and other works more particularly described:

1914 cubist still life [pen drawing] fine one over piano upper right, above cubist one. Terrace, subtle copper colored one 1930–31. c. 1916 flowered piece like Vitali. Beautiful one behind 1910 landscape with 2 blue bottles 1939 [sic] 1939 X (1 photo). Landscape with white building over bed in bedroom. Bedroom: brown still life 2 seashells & coral. Bedroom: still life with yellow bottle at right of bed. Has 2 pictures 2 white bottles, a spool[?] & the yellow bottle or oilcan [sic] gas can, 1942 [sic] 43, or 44 (photo 3) Shown us on chair in bedroom. Little one: 2 blue bottles, teapot, cup with red bond around top (no 2 photo X). Late white one – photo 4 Landscape with white b[ui]ld[in]g photo 5.55

In addition to the characterizations of the three great protagonists of the scuola metafisica discussed thus far, the notebooks contain annotations and opinions concerning minor followers or sympathizers and their individual works, which further illustrate the “Metaphysical” content of Italian art. Most are briefly mentioned, and only some were eventually selected for the show – typically those that boasted a Parisian pedigree. Savinio’s works were properly placed within the “Metaphysical” framework – he was the co-inventor, with de Chirico, of Metaphysical art – but they were not chosen because those seen by both curators as too late and not suitable to represent his poetic affinity with his more famous brother. They included Annunciazione (Annunciation, 1932), according to Soby “his most memorable image […] with that strange duck-billed figure!”; and Corteo di Nettuno (Procession of Neptune, 1939), which seemed to him, at first glance, “very Ernst-Magritte.” These last comments appear in a letter of August 19, 1948, in which Soby asserts: “Savinio doesn’t seem to me any great shakes as a painter, and I should think two pictures enough, as we both originally said.”56

In Jesi’s collection, they noted Pesci sacri (Sacred Fish, 1925) by the Ferrara-born artist Filippo De Pisis, who could be associated with the scuola metafisica for his work’s dreamy atmospheres and focus on inanimate and eternal objects. The painting struck the curators for its similarity with the eponymous painting by de Chirico – “Pesci sacri with Chinese vase as a painting by [de] Chirico”57 – but it was not selected for the show. Neither was the 1922 “metaphysical nude in Renaissance interior”58 by Massimo Campigli that they saw at the recently opened Galleria L’Obelisco (1946), run by the couple Irene Brin and Gaspero del Corso in Rome.

Two works by Mario Sironi, one described as “Composizione metafisica – Mannequin with African Mask,”59 and the other, representing a “Newspaper woman & steamship,” entitled La moglie del pescatore (The Fisherman’s Wife, 1919), in the Boschi collection, were impressive for their collage-like appearance, dark tones, and low atmosphere; of Jucker’s collection, Barr and Soby recorded that Sironi’s small composition “Interno metafisico con manichino contains number 2 / 4,”60 in accordance with a Cubist and Futurist-inspired practice. Many other works by Sironi were seen at Margherita Sarfatti’s house, the Jewish critic and journalist linked to Benito Mussolini. Despite a general predilection for one of his Metaphysical “factory scenes,” highlighted in the notebooks with an “X” and described in detail by Scolari Barr’s comment (“factory scene somewhat larger with long truck on road shadow of man in left center blue sky going white at horizon”61), in the end only his so-called “pictographic compositions” of the 1940s were featured in Twentieth-Century Italian Art. Thus, his participation in the pro-Fascist Novecento group was strategically eluded.62 The few lines dedicated to the artist in the catalogue once again reveal the political-cultural message of the exhibition: the metaphysical-abstract experience of Sironi’s art and his dark expressive intensity are emphasized, while the implications of the neo-classical pomposity that appealed to Mussolini are devalued in the curators’ portrayal of him as a solitary artist with a “powerful romantic expressionism which seems to have been developed independently, being as closely related to the seventeenth-century Italian Baroque as to the art of [Georges] Rouault.”63 A similar interpretative key was also applied to distinguish Morandi as the embodiment, for the Americans, of the existentialist artist and the values of anti-fascism, considering him as the champion of an aesthetic, moral, and plastic “rebirth.”

In the catalogue, the “Metaphysical” label was extended to include: “non-representational” paintings by Corrado Cagli filled with “an element of enigmatic mystery” deeply inspired by de Chirico’s metaphysical art;64 Fantastic-Surrealistic graphic works by Giuseppe Viviani and Fabricio Clerici, seen as “a continuation of the native ‘metaphysical’ school, as carried on by Alberto Savinio”;65 and recent works by Salvatore Fiume that revived “the scuola metafisica in its original, powerful stages,”66 for example, his Isole di statue (Island of Statues, 1948), which was, in Soby’s estimation, essentially a tribute to de Chirico’s iconic Disquieting Muses.

Bibliography

Arcangeli, Francesco. “Tre pittori italiani dal 1910 al 1920.” In XXIV Biennale di Venezia, 29–32. Venice: Edizioni Serenissima, 1948. Exhibition catalogue.

Baldacci, Paolo. “Giorgio de Chirico ripetitore seriale tra ‘aura’ e mercato. Il caso Muse inquietanti.” Studi OnLine 5, nos. 9–10 (January/December 2018): 5–14

Baldacci, Paolo, and Roos, Gerd. Piazza d’Italia (Souvenir d’Italie, 2) 1913 (July–August 1933): A Post-War Trail: De Chirico’s Strategy Against Modernism. Milan: Scalpendi/Archivio dell’Arte Metafisica, 2013.

Barr, Alfred H., Jr., and Soby, James Thrall, eds. Twentieth-Century Italian Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949. Exhibition catalogue.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949.” Oxford Art Journal 35, no. 2 (June 2012): 147–69.

Bignami, Silvia, and Colombo, Davide. “Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and James Thrall Soby’s Grand Tour of Italy,” in Raffaele Bedarida, Silvia Bignami, and Davide Colombo (eds.), Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 3 (January 2020), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alfred-h-barr-jr-and-james-thrall-sobys-grand-tour-of-italy/, accessed February 24, 2020.

Braun, Emily, ed. Giorgio De Chirico and America. Turin: Allemandi, 1996. Exhibition catalogue.

Braun, Emily. Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics under Fascism. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Cecchini, Laura Moure. “‘Positively the only person who is really interested in the show’: Romeo Toninelli, Collector and Cultural Diplomat Between Milan and New York,” in Raffaele Bedarida, Silvia Bignami, and Davide Colombo (eds.), Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 3 (January 2020), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/positively-the-only-person-who-is-really-interested-in-the-show-romeo-toninelli-collector-and-cultural-diplomat-between-milan-and-new-york/, accessed February 24, 2020.

Colombo, Davide. “1949: Twentieth-Century Italian Art al MoMA di New York.” In New York, New York. La riscoperta dell’America, edited by Francesco Tedeschi, 102–09. Milan: Electa, 2017. Exhibition catalogue.

Contemporary Art: Official Catalog, Department of Fine Arts, Division of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture. San Francisco: Golden Gate International Exposition, 1939. Exhibition catalogue.

Cordova, Elena. “Discoveries from the Margaret Scolari Barr Papers at the MoMA Archives.” Paper presented at “A Study Day on Alfred Barr and Margaret Scolari Barr,” Center for Italian Modern Art, New York, April 2015.

Cortesini, Sergio. ‘One day we must meet’: Le sfide dell’arte e dell’architettura italiane in America (1933–1941). Monza: Johan & Levi, 2018.

De Chirico. Gli anni Trenta, edited by Fagiolo dell’Arco. Milan: Skira, 1995.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Il ritorno al mestiere.” In Giorgio de Chirico. Il meccanismo del pensiero: Critica, polemica, autobiografia, 1911–1943, edited by Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, 93–99. Turin: Einaudi, 1995. Originally published in Valori plastici 1, nos. 11–12 (1919): 15–18.

Devree, Howard. “A Reviewer’s Notebook: Comment on Some of the Newly Opened Exhibitions Oils, Water-Colors, Prints.” New York Times, April 11, 1937.

Fergonzi, Flavio. “Un contratto inedito tra Giorgio Morandi e Mario Broglio: Identificazioni delle opere, storia collezionistica e novità cronologiche del Morandi metafisico e postmetafisico.” Saggi e Memorie di storia dell’arte, no. 26 (2004): 459–515.

Fergonzi, Flavio. La collezione Mattioli. Capolavori dell’avanguardia italiana. Milan: Skira, 2003.

Kachur, Lewis. Displaying the Marvelous: Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, and Surrealist Exhibition Installations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Koob, Pamela. “James Thrall Soby and De Chirico.” In Giorgio De Chirico and America, edited by Emily Braun, 111–23. Turin: Allemandi, 1996. Exhibition catalogue.

Mocchi, Nicol Maria. “‘Talk with Savinio – May 1, 1948 Milan.’ Le ‘rivelazioni’ di Alberto Savinio a James Thrall Soby sull’arte metafisica, dalle origini ai falsi.” Studi OnLine 5, nos. 9–10 (2018): 51–70.

Mocchi, Nicol Maria. “Twentieth-Century Italian Art 1949: il caso Morandi.” In New York, New York. La riscoperta dell’America, edited by Francesco Tedeschi, 110–16. Milan: Electa, 2017. Exhibition catalogue.

Rishel, Joseph J. “Morandi and America: A Brief Survey of His Fortunes in the English-Speaking World.” In The Later Morandi. Still Lifes 1950–1964, edited by Laura Mattioli Rossi, 51–58. Milan: Mazzotta, 1998. Exhibition catalogue.

Rovati, Federica. Carrà tra futurismo e metafisica. Milan: Scalpendi/Archivio dell’Arte Metafisica, 2011.

Selleri, Lorenza. “Morandi on Either Side of the Atlantic: Critics, Collectors, and Dealers in Europe and the Americas.” In Giorgio Morandi 1890–1964, edited by Maria Cristina Bandera and Renato Miracco, 174–85. Milan: Skira, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Soby, James Thrall. “Presentazione.” In Arte italiana del XX secolo da collezioni americane, edited by James Thrall Soby and Palma Bucarelli, 14–23. Milan: Silvana Editoriale d’Arte, 1960. Exhibition catalogue.

Soby, James Thrall. “A visit to Morandi.” In Giorgio Morandi, edited by Jean Leymarie, Lamberto Vitali and Gabriel White, 5–6. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1970. Exhibition catalogue.

How to cite

Nicol Maria Mocchi, “‘Chiricos checked’: Metaphysical Art in James Thrall Soby’s Notebooks, Spring 1948,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- This text is a transcript of a speech given at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York, on April 26, 2019. It has been lightly edited for publication.

- On the exhibition and its sociopolitical implications, see Raffaele Bedarida, “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949,” Oxford Art Journal 35, no. 2 (June 2012): 147–69.

- In the Archives of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, see the James Thrall Soby (herafter, JTS) Papers, namely a travel diary labeled “Milan,” III.E.1, and two notebooks labeled “Milan II–X,” and “Rome,” I.135; for other documentary sources, including extensive correspondence, writings, and records related to this journey, see the Margaret Scholari Barr (MSB) Papers, Agendas, Travel Diaries, and Address Books, VI.5, especially a travel diary dated 1948; and the Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (AHB) Papers, Twentieth-Century Italian Art [MoMA Exh. #413, June 28–September 18, 1949], III.21 mf 3153 to III.27 mf 3154, and the two travel notebooks of 1948, “Italy, France, and Switzerland,” XIII.30, and “Venice, Italy and Paris, France,” XIII.32 mf 3260 to 3261. All future references to letters, notebooks, and diaries, unless otherwise noted, are from MoMA’s Archive.

- Silvia Bignami and Davide Colombo, “Two Americans in Italy: Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and James T. Soby at the Venice Biennale and Rome Quadriennale,” paper presented at “Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s Twentieth-Century Italian Art (1949),” study day at CIMA, February 2019 (now published as Silvia Bignami and Davide Colombo, “Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and James Thrall Soby’s Grand Tour of Italy,” in Raffaele Bedarida, Silvia Bignami, and Davide Colombo (eds.), Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 3 (January 2020), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/alfred-h-barr-jr-and-james-thrall-sobys-grand-tour-of-italy/, accessed February 24, 2020) which further expands Colombo’s essay “1949: Twentieth-Century Italian Art al MoMA di New York,” in New York, New York. La riscoperta dell’America, ed. Francesco Tedeschi (Milan: Electa, 2017), 102–09. I wish to thank both Silvia Bignami and Davide Colombo for their advice and for generously sharing their thoughts about this with me.

- Elena Cordova, “Discoveries from the Margaret Scolari Barr Papers at the MoMA Archives,” paper presented at “A Study Day on Alfred Barr and Margaret Scolari Barr,” CIMA, April 2015

- Other pocket diaries penned by Soby, related to his various international journeys, contain also sporadic personal annotations (e.g., restaurants, bars, places to visit). See JTS Papers, Pocket Diaries, III.E.1, in particular those dated 1948–50.

- Alfred H. Barr, Jr, and James Thrall Soby, eds., Twentieth-Century Italian Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 128.

- During World War I, de Chirico and Carrà were both sent by the military command to Ferrara, where they established the short-lived scuola metafisica, later joined by the Bologna-based Morandi. This “was fundamentally a rationalization of the art de Chirico had been creating in Paris from 1912 to 1915.” Barr and Soby, Twentieth-Century Italian Art, 17.

- See Francesco Arcangeli, “Tre pittori italiani dal 1910 al 1920,” in XXIV Biennale di Venezia (Venice: Edizioni Serenissima, 1948), 29–32.

- Modern Art, Old and New (New York: Georgette Passedoit Gallery, April 11–24, 1937). See also Howard Devree, “A Reviewer’s Notebook: Comment on Some of the Newly Opened Exhibitions Oils, Water-Colors, Prints,” New York Times, April 11, 1937: “Carlo Carrà, the Italian futurist, is represented by two of his well-known and typical pictures of 1917, ‘Penelope’ and ‘The Occidental Knight,’ and these, together with Chirico’s even earlier ‘Mysterious Departure,’ similar in vein to the ‘Delights of the Poet,’ serve the purpose of a historical background for the group. […] Morandi’s small harmonic still-lifes […] are other interesting items.” On the Valori plastici group and Mario Girardon’s overseas activities, see Flavio Fergonzi, “Un contratto inedito tra Giorgio Morandi e Mario Broglio. Identificazioni delle opere, storia collezionistica e novità cronologiche del Morandi metafisico e postmetafisico,” Saggi e Memorie di storia dell’arte, no. 26 (2004): 459–515, especially 507.

- Contemporary Art: Official Catalog, Department of Fine Arts, Division of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture (San Francisco: Golden Gate International Exposition, 1939): nos. 5, 12, 24.

- Barr and Soby, Twentieth-Century Italian Art, 15 and 17.

- Exhibitions ranged from private initiatives headed by Dario Sabatello and Laetizia Pecci Blunt, owners of the Comet Art Gallery in New York [1937–38]; to more official international trade fairs and shows such as the Chicago Century of Progress World’s Fair of 1933–34 and the New York World’s Fair of 1939–40; up to the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, which generally favored classically-rooted Italian art movements and poetics, such as Novecento and Strapaese. See also Sergio Cortesini, ‘One day we must meet’: Le sfide dell’arte e dell’architettura italiane in America (1933–1941) (Monza: Johan & Levi, 2018).

- See James Thrall Soby, “A visit to Morandi,” in Giorgio Morandi, ed. Jean Leymarie, Lamberto Vitali, and Gabriel White (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1970), 5: “We [Soby and Barr] found that most of the important collections of contemporary Italian art had been formed in affluent Milan, sometimes by men of inherited wealth but more often by professional and business people who had exchanged their services or goods for paintings and sculptures by living artists.”

- See, for example, James T. Soby’s letter to Monroe Wheeler, February 9, 1949, AHB Papers, III.23: “It is clearly absolutely impossible for us to delegate the choice of works to the Italians. Pressure from older artists in Milan like Carrà, Tosi, Funi and Marussig (the latter two are not in the show at all) accounts for the fact that the Italians want recent works by the older artists, but these recent works are mostly feeble in quality and Alfred and I feel they would weaken the show. […] The Italians seem to suspect here a commercial interest in the younger men. […] But obviously we must show the younger painters explaining clearly that the Museum has always shown works of art which are for sale and has taken a commission of 10% on sales made.” On Toninelli’s role in arranging the MoMA show, and his problematic interactions with other dealers and collectors, see Laura Moure Cecchini, “‘Positively the only person who is really interested in the show’: Romeo Toninelli, Collector and Cultural Diplomat Between Milan and New York,” in Raffaele Bedarida, Silvia Bignami, and Davide Colombo (eds.), Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 3 (January 2020), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/positively-the-only-person-who-is-really-interested-in-the-show-romeo-toninelli-collector-and-cultural-diplomat-between-milan-and-new-york/, accessed February 24, 2020.

- James T. Soby, letter to Monroe Wheeler, February 9, 1949, AHB Papers, III.23. On Frua De Angeli, there is also this precious comment: “His pictures do not hang in his house, but are merely stored in racks.”

- Soby, letter to Lamberto Vitali, March 1, 1949, AHB Papers, III.23.

- In his “Surrealist Manifesto” (1924), André Breton introduced “the modern mannequin” as well as “any other symbol capable of affecting the human sensibility for a period of time” as instances of the “marvelous.” See Lewis Kachur, Displaying the Marvelous: Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, and Surrealist Exhibition Installations (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

- Cubism was at the core of Barr’s narrative of modern art history and of the most recent developments in abstract art, as exemplified in his groundbreaking exhibitions at MoMA, most notably Cubism and Abstract Art (1936) and Picasso: Forty Years of His Art (1939/40).

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan X–II.”

- JTS Papers, III.E.1, “Milan.”

- Soby’s personal involvement in the Metaphysical art section is exemplified in a March 1949 letter to Barr, AHB Papers, III.23: “Don’t for heaven’s sake worry about the Futurist section not being adequate. I don’t plan anything at all elaborate for the scuola metafisica – no footnotes and nothing scholarly in the least. I think a fairly bald account of what the movement was and who was involved should do the trick and run to perhaps 10 or 12 double-spaced typewritten pages. […] Anyway, I’m grateful that you can tackle the Futurist section. I have done a lot of detailed work on the scuola but simply because the material was there and I couldn’t resist picking at de Chirico’s bones on the way. I don’t intend to use such detailed information, but I had to have it in order to decipher what in hell did go on in Ferrara, where Morandi was, etc. All takes time, since the written material on the subject is very, very scanty. The dates have to be checked six times apiece, at a minimum. Oddly enough de C[hirico] is usually right — that old exact-dater!” For further insights, see Pamela Koob, “James Thrall Soby and De Chirico,” in Giorgio de Chirico and America, ed. Emily Braun (Turin: Allemandi, 1996), 111–23.

- See [Charles Wertenbaker], “Art: Counterfeits Preferred,” Time – The Weekly Newsmagazine 48, no. 9 (August 26, 1946), 42–44: “[De Chirico] had just received from U.S. James Thrall Soby’s definitive book The Early Chirico (Dodd, Mead, $3), and denounced as ‘forgeries’ two reproductions in it, one of them The Double Dream of Spring (see cut).” Soby’s answer, also published in Time (September 2, 1946): “However odd it may seem for a critic to insist that a man painted a picture which he says he did not paint, I disagree flatly with De Chirico. I think he painted The Double Dream of Spring, and I plan to publish the lengthy evidence for this assertion in a new edition of the book. […] I hope to go on defending him against all comers, including his aging, naked, grandiose, disgraceful, his rather wonderful self.” On this, see Paolo Baldacci and Gerd Roos, eds., Piazza d’Italia (Souvenir d’Italie, 2) 1913 (July–August 1933): A Post-War Trail: De Chirico’s Strategy Against Modernism (Milan: Scalpendi/Archivio dell’Arte Metafisica, 2013), 17–18; and Koob, “James Thrall Soby and De Chirico.”

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan X–II.” See Nicol M. Mocchi, “‘Talk with Savinio – May 1, 1948 Milan.’ Le ‘rivelazioni’ di Alberto Savinio a James Thrall Soby sull’arte metafisica, dalle origini ai falsi,” Studi OnLine 5, nos. 9–10 (2018): 51–70.

- See Paolo Baldacci, “Giorgio de Chirico ripetitore seriale tra ‘aura’ e mercato. Il caso Muse inquietanti,” Studi OnLine 5, nos. 9–10 (2018): 5–14.

- MoMA showed an increasing interest in buying it, see Barr’s letter to Pietro Feroldi, September 17, 1948, JTS Papers, “Italian Corr.-Miscellaneous,” I.136: “I remember that during our delightful visit to your collection in Brescia our Milanese host, Toninelli, with our permission, discussed the possible purchase of the [de] Chirico Muse Inquietanti. The price which he mentioned to us was, however, so high that we did not pursue the matter further at that time.” A year later, on August 7, 1949, Barr wrote to Stephen C. Clark, a MoMA Trustee, JTS Papers, “Exh. Correspondence I,” I.135: “We were unable to get the de Chirico Disquieting Muses because the owner [Pietro Feroldi] decided in the end to sell his whole collection for a high figure to another Italian [Gianni Mattioli] who has set up a foundation to receive it.” For more details, see Flavio Fergonzi, La collezione Mattioli. Capolavori dell’avanguardia italiana (Milan: Skira, 2003).

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Rome.”

- Soby, letter to Barr, August 29, 1948, AHB Papers, III.23.

- JTS Papers, III.E.1, “Milan.” In De Chirico. Gli anni Trenta, ed. Fagiolo dell’Arco (Milan: Skira, 1995), 328, the two Piazza d’Italia are reproduced as follows: Piazza d’Italia (con Arianna), 1915 [1939], and Piazza d’Italia (con statua), 1915 [1939], figures 26 and 28. I thank Gerd Roos for helping me identify these paintings.

- The work is now in MoMA’s collection. See Barr, letter to Carlo Frua De Angeli, November 8, 1949, JTS Papers, “Exh. Correspondence I,” I.135: “[…] you have heard from Mr. [Gustavo] Bacchi, arrangements are being made through him for the purchase of the de Chirico Sacred Fish. The sum of $1305 is being paid to you through Italeuropa, the shipping company in Milan, the balance as you directed.”

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Rome.” In De Chirico. Gli anni Trenta, ed. Fagiolo dell’Arco, 325, figure 21, it is identified as Piazza d’Italia (con Arianna e faro), 1912 [1939–40].

- JTS Papers, III.E.1, “Milan.”

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan II–X.” Likely to be identified as L’enigma del politico, 1915 [1939–40], in De Chirico. Gli anni Trenta, ed. Fagiolo dell’Arco, 329, figure 29.

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan II–X.”

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Rome.” These three pencil-on-paper drawings by de Chirico can be identified as follows: La malinconia (Melancholy, 1915; 13 3/16 x 10 53/64 inches [33.5 x 27.5 cm]); Il manichino pittore (The Mannequin Painter, 1918; 16 9/64 x 12 13/32 inches [41 x 31.5 cm]); Manichino e due personaggi (Mannequin and Two Figures, 1919; 15 3/4 x 12 13/64 inches [40 x 31 cm]). All are presently in private collections.

- See Giorgio de Chirico, “Il ritorno al mestiere,” in Giorgio de Chirico. Il meccanismo del pensiero: Critica, polemica, autobiografia, 1911–1943, ed. Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco (Turin: Einaudi, 1995), 93–99. Originally published in Valori plastici 1, nos. 11–12 (1919): 15–18.

- This painting, among others such as Carrà’s Hermaphroditic Idol and a Morandi’s Still life, respectively owned by Frua De Angeli and Roberto Longhi, suffered little damage in the exhibition, as documented in the “Report of condition of works lent to exhibition 20th Century-Italian Art,” attached to a letter addressed to June Hesener, December 5, 1949, AHB Papers, III.22.

- Soby, letter to Barr, August 29, 1948, AHB Papers, III.23.

- Soby, letter to Barr, May 22, 1948, AHB Papers, III.27.

- On Carrà’s Metaphysical phase, see Federica Rovati, Carrà tra futurismo e metafisica (Milan: Scalpendi/Archivio dell’Arte Metafisica, 2011).

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan X–II.”

- See Soby, letter to Barr, n.d., AHB Papers, III.23: “Carrà is a real problem. Of the metaphysical ones you marked at the Biennale, I’ve left out of the list only Penelope, which seems still very cubist and hence not as important for this section. The best two pictures in sheer quality seem to me to be the Gentiluomo Ubriaco (Frua) and L’amante dell’ingegnere (Feroldi), followed perhaps by [Sigfried] Giedion’s Solitude (despite its debt to [de] Chirico, in fact perhaps because of it), and Pallini’s Cavaliere Occidentale. Jesi’s Madre e figlio gives the full Carrà metaphysical works. […] Have added the fascinating Casa dell’amore of 1922.”

- Soby, letter to Barr, August 29, 1948, AHB Papers, III.23.

- JTS Papers, III.E.1, “Milan.”

- On this issue, see Cecchini, “Positively the only person who is really interested in the show,” especially 10–12.

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan.” The painting, from Ghiringhelli’s collection (Galleria del Milione, Milan), was shortly afterwards lent to the XXIV Venice Biennale (“Tre pittori italiani dal 1910 al 1920,” 31, no. 1), and entered Jucker’s collection in the mid-1950s. I thank Daniela Ferrari and Stella Seitun for sharing their extensive knowledge of Carrà’s artwork with me.

- Barr and Soby, Twentieth-Century Italian Art, 132.

- Ibid., 23.

- “Divenimmo convinti dell’autenticità e del valore della sottile, poetica, sofferta arte morandiana.” James Thrall Soby, “Presentazione,” in Arte italiana del XX secolo da collezioni americane, ed. James Thrall Soby and Palma Bucarelli (Milan: Silvana Editoriale d’Arte, 1960), 21.

- On Morandi’s North American fortunes, see Joseph J. Rishel, “Morandi and America: A Brief Survey of His Fortunes in the English-Speaking World,” in The Later Morandi. Still Lifes 1950–1964, ed. Laura Mattioli Rossi (Milan: Mazzotta, 1998), 51–58; Lorenza Selleri, “Morandi on Either Side of the Atlantic: Critics, Collectors, and Dealers in Europe and the Americas,” in Giorgio Morandi 1890–1964, ed. Maria Cristina Bandera and Renato Miracco (Milan: Skira, 2008), 174–85; and Nicol M. Mocchi, “Twentieth-Century Italian Art 1949. Il caso Morandi,” in Tedeschi, New York, New York, 110–16.

- Soby, “A visit to Morandi,” 5.

- AHB Papers, XIII.30 mf 3261, “Italy, France, and Switzerland.”

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan X–II.”

- Soby, letter to Barr, August 29, 1948, AHB Papers, III.23.

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Rome.”

- Soby, letter to Barr, August 19, 1948, Twentieth-Century Italian Art exhibition records, 413.6. I thank Davide Colombo for bringing this letter to my attention.

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan X–II.”

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Rome.”

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Milan X–II.”

- Ibid.

- JTS Papers, I.135, “Rome.”

- On Sironi, see Emily Braun, Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics under Fascism (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2000), especially the chapter “Sironi in Context,” 1–17.

- Barr and Soby, Twentieth-Century Italian Art, 27.

- Ibid., 33.

- Ibid., 31.

- Ibid.