Metaphysical Writing and the “Return to Order”: Artistic Theorization and Modernist Magazines Between 1916 and 1922

Simona Storchi Simona Storchi Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, Issue 4, July 2020https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/metaphysical-masterpieces-1916-1920-morandi-sironi-and-carra/

This article looks at the extensive theorization and critical activity carried out by the artists involved in the Metaphysical movement between 1916 and 1922, with particular reference to the writings of Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico. Focusing primarily on the magazines La Brigata, La Raccolta, Valori plastici, La Ronda, Il primato artistico italiano and Il Convegno, published in the crucial years between World War I and the rise of Fascism (with the exception of Il Convegno, which was published between 1920 and 1939), the article explores how these writings contributed to the theorization of Metaphysical Art and it considers their essential role in shaping the artistic debate in Italy in the years of the so-called “return to order.” It assesses the role played by Metaphysical writing in the demise of avant-garde aesthetics and in the promotion of a revision of the relationship between art and politics, which saw a reconceptualization of the classical as central to the redefinition of postwar national culture. It discusses some of the aesthetic and ideological implications attached to the redefinition of the idea of the classical in the postwar context, with particular reference to the centrality attributed to Italy in the renewal of European art.

Introduction

In Italy, during the early twentieth century, the press, including periodicals, played a key role in Italian public, political, and cultural life, as the country rapidly evolved and came to face the challenges of modernity.1 Literary, artistic, and cultural magazines were not only a means of communication, but also a distinctive space of cultural production – a new public sphere – following the demise of the old aristocratic circles constituted by the courts and the salons. Scholars have referred to the twentieth century as “the century of the periodicals” to highlight the significance of magazines in shaping its modern culture.2 As noted by Victoria de Grazia, in a society such as that of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Italy, in which the interests of the middle class were as yet poorly organized, writers, artists, and academics who rounded out their income through journalistic writing played a uniquely important role in forming public opinion.3 A distinguishing feature of magazine culture was its militancy. It dealt with current events, concerned itself with eccentric and non-canonical areas of knowledge, and its style was accessible and often polemical. The readership of cultural magazines was not intended to be an elite, although it was not a mass. These publications were mostly aimed at an educated, though not erudite, public. Critics have noted how magazines were rooted in oral culture: they were often born as a result of conversations, meetings, and exchanges. Their creation and development were almost a collective effort, by groups of intellectuals often formed through personal relations rather than fixed cultural programs, and this favored a flexibility of collaborations across the arts.4 Magazines, as Sascha Bru has put it, “came to function as laboratories for new ideas, in culture and politics, as well as in art and literature.”5

In the crucial years between 1916 and 1922, the protagonists of Metaphysical art engaged in intense writing activity, driven mostly by explanatory or theorizing intents, though monetary concerns should not be excluded as important factors in the proliferation of articles, essays, reviews, and other written musings and reflections published in these years.6 Periodicals and magazines offered much-needed space for artistic theorization and debate, increased the visibility of artists and their works (some editors also organized exhibitions and bought and sold some of the works),7 and could provide a source of income, at a time when a small work or a drawing by de Chirico could fetch little more than an article in a periodical.8 Some were very small magazines, such as La Brigata and La Raccolta, published in provincial towns (both were based in Bologna), away from the main cultural centers of Milan, Florence, and Rome; they typically featured less than twenty pages, were published during the war, and relied on a limited number of contributors. The editors were sometimes hardly more experienced than students (this was the case for La Raccolta). Nonetheless, these publications became important forums for artistic debates and exchanges, were charged with high expectations in terms of their cultural mission, and hosted articles by major artists and influential critics and promoters.

This article will focus on Carlo Carrà’s and Giorgio de Chirico’s writings published in cultural periodicals and magazines between 1916 and 1922. The articles and illustrations of these two prolific writers trace their artistic development and expound the aesthetic theorization underpinning their respective bodies of work. Their essays and articles provided a self-exegetical, theoretical, and critical corpus which complements, elucidates, and enriches their artistic output and, at the time, contributed to the shaping of artistic debates. They constituted significant interventions in current debates on the postwar “return to order,” providing key interpretations of the classical which would reverberate throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Carlo Carrà, between Giotto and Canova: The Pursuit of “Italianness”

Despite being a leading figure of Futurist painting and theorization, during the war years Carrà had grown increasingly uncomfortable with the ideas and forms of Futurist art. He later recalled that his detachment from Futurism had been caused by a “very strong desire to identify [his] painting with history, especially Italian art history,” and to “find that necessary balance between art and tradition and between art and nature which Futurism had denied.”9 Carrà theorized this transition in three essays published in the Florentine magazine La Voce in 1916: “Parlata su Giotto” (Speech on Giotto), “Paolo Uccello costruttore” (Paolo Uccello the Constructor), and “Le parentesi dell’io” (The Parentheses of the I). They marked his detachment from the aesthetics of Futurism and expressed his increasing preoccupation with finding a synthesis between tradition and modernity through the recovery of pictorial plasticità.10 In these essays, Carrà attempted to reverse the traditional emphasis on the art of Michelangelo and Raphael when considering the development of the Italian artistic tradition, underscoring instead the “plastic” qualities of earlier masters. He attributed to Giotto’s and Uccello’s art “spiritual” as well as pictorial qualities, with which he found a personal affinity; he professed to be pursuing the “architectural” principle in art and declared himself to be living and working in solitude, with a feeling of “primordial expectation,” “to create the new European painting.”11 Also in 1916, Carrà produced a series of paintings – Antigrazioso (Anti-gracious), Ricordi d’infanzia (Childhood Memories), and La Carrozzella (The Carriage) – characterized by an archaic quality, which combined strong outlines and solid objects with a sense of estrangement generated by the human figures’ lack of naturalness. The result was a timeless and motionless representation, which was the opposite of Futurist speed and dynamism. His meeting with de Chirico at the Villa Seminario near Ferrara in 1917, where both artists were hospitalized during the First World War, resulted in Carrà’s turn to Metaphysical painting as a way of expressing the lyrical essence of everyday objects. Resulting from Carrà’s acquaintance with de Chirico were his 1917 paintings Solitudine (Solitude), La camera incantata (The Enchanted Chamber), Madre e figlio (Mother and Son), and La musa metafisica (The Metaphysical Muse).

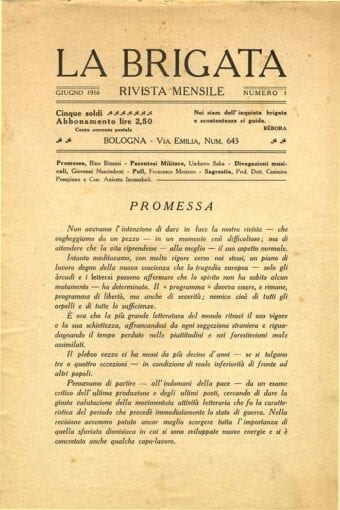

Some of Carrà’s works produced between 1916 and 1917 appeared in the small magazine La Brigata, edited by Bino Binazzi and Francesco Meriano12 and published in Bologna every month or two between 1916 and 1917, with a single issue published in 1918, in April, and another in 1919, in June (figure 1).13 The periodical was affected by the war in its contents, pagination, and irregular publication schedule: hence, despite the indication of its subtitle, Rivista mensile, it did not come out as a regular monthly; and the number of pages varied from sixteen to twenty-six, with the exception of the last, eight-page issue. Nonetheless, La Brigata was an ambitious magazine, pervaded by a strong sense of national culture and a desire for disenfranchisement from foreign influences.14 Despite the constraints of the war years, and its being mostly written by Binazzi and Meriano (who also financed much of the project), La Brigata hosted contributions by notable writers and poets such as Umberto Saba, Sibilla Aleramo, Massimo Bontempelli, Clemente Rebora, Alberto Savinio, Corrado Alvaro, Camillo Sbarbaro, Ada Negri, and Guillaume Apollinaire.15 La Brigata also had international reach: in December 1916, the magazine proudly declared that it had received attention from Italian newspapers, Argentinian and Romanian magazines, the renowned Parisian newspaper Le Temps, and Hugo Ball’s Zurich-based Dada magazine Cabaret Voltaire.16

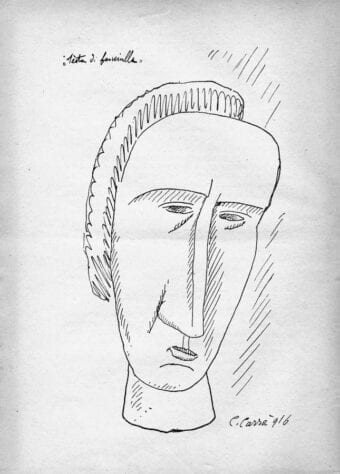

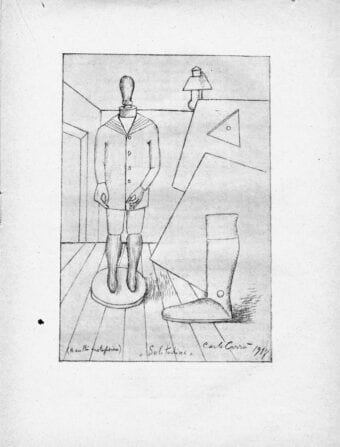

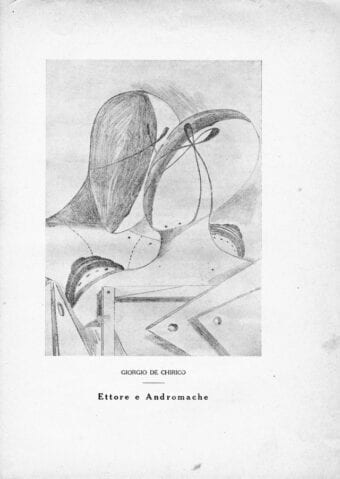

La Brigata published a poem by Carrà titled “Marcia nell’aurora” (March at Sunrise, 1917),17 as well as illustrations of works by him reflecting a transition from his quest for simple forms and linearity, following his Futurist phase, to his early Metaphysical paintings; these were La Massaia (The Housewife, 1916), Testa di fanciulla (Girl’s Head, 1916; figure 2), Testa di giovane gentiluomo (Young Gentleman’s Head, 1916), Costruzione lineare di un bicchiere (Linear Construction of a Glass, 1916), and Solitudine (realtà metafisica) (Solitude [Metaphysical Reality], 1917; figure 3). It also published an illustration of de Chirico’s Ettore e Andromache (Hector and Andromache, 1917; figure 4), which was his first drawing to appear in an Italian publication.18

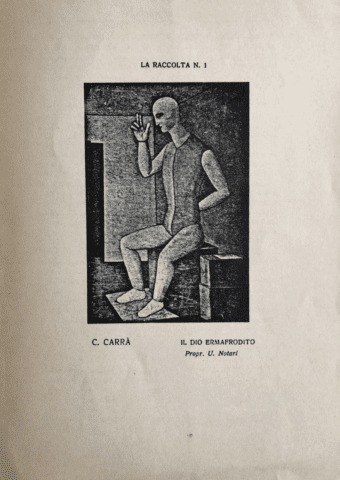

By late 1917 the near-regular publication of La Brigata was ceasing,19 but a new Bolognese magazine would soon become a significant forum for post-avant-garde debate in Italy: La Raccolta was published on a monthly basis between March 1918 and February 1919 (figure 5). The editor was the young writer and critic Giuseppe Raimondi, who was joined by a small group of regular contributors, namely Riccardo Bacchelli, Vincenzo Cardarelli, Lorenzo Montano, and Aurelio Saffi (who subsequently became the founding group of the Roman magazine La Ronda, in 1919).20 It published illustrations by Carrà, de Chirico, Giorgio Morandi, and Ardengo Soffici, as well as writings by Soffici and Carrà. La Raccolta consciously presented itself as a periodical of reaction, particularly against the prewar avant-garde, and aspired to be a platform for a postwar rethinking of Italian art along the lines of a rediscovered national tradition. It advocated an “Italian plastic renaissance” that was “capable of bringing art back within the safe and perfect boundaries of tradition, through a calm and collected sensibility and rising above the easy novelty and the frantic esoteric quests of the latest artistic phenomena.”21 Within this program, it promoted the Metaphysical artists, particularly Carrà, who contributed substantially to the magazine, with both writings and illustrations. La Raccolta featured reproductions of Carrà’s Il dio ermafrodito (The Hermaphrodite God, 1917; figure 6), L’apparizione della primavera (The Apparition of Spring, 1917), and a Natura morta (Still Life, 1917), as well as de Chirico’s Natura morta evangelica (Evangelical Still Life, 1917) and two still lifes by Morandi.

Carrà did not use La Raccolta as a platform to expound his interpretation of Metaphysical painting (he would do that in a later volume, titled Pittura metafisica, published by Vallecchi in 1919). Instead, he published a series of articles in which he traced the history and motivation of his recent artistic trajectory. This had in part been elucidated in a self-presentation he wrote for a personal exhibition catalogue at the Chini gallery in Milan in December 1917. In it, Carrà claimed to have revived the “plastic virtues” of the Italian “race” expressed by the Italian primitives (Giotto, Masaccio, Paolo Uccello); he interpreted recent Italian art (including Futurism) in anti-Impressionist terms, writing that it was informed by the pursuit of the “constructing principle,” which he defined as based on solid forms placed in an abstract atmosphere. He then declared that he was working to give his country “a really new art, both in its form and in its substance.”22

The first of Carrà’s contributions to La Raccolta was a quasi-allegorical prose piece in three sections – “Il ritorno di Tobia” (The Return of Tobia), followed by the two-part “Tobia Futurista” (Tobia the Futurist)23 – about the fictional character Tobia, who is an artist. Upon returning to his father’s home after having been away, Tobia is confronted by a reality that presents itself in forms and images belonging to the Metaphysical imaginary: a clock on a circular tower, propellers, papier-mâché globes, thermometers, blackboards, puppets, and everyday objects invested with a specter-like appearance. Tobia’s return from his journey allows him to see reality as a transfigured landscape of geometry and silence; familiar things are surrounded by an aura of disturbing mystery, and their meaning appears renewed.

This new outlook on the objects of everyday life through the “Metaphysical” eye was already a feature of de Chirico’s painting. Since 1916, Carrà had been elaborating it into a poetics of the ordinary object, in accordance with his quest for a more essential, spiritual art that could capture the transcendent essence of phenomenal reality.24 In this way, he set out the almost platonic concept of forms that critic Elena Pontiggia sees as a key element of modern classicism in the interwar years.25 “Tobia Futurista” revisited Tobia’s creative phases, including Futurism, as part of a cultural mission intended to emancipate Italian art from foreign influences and to revive its artistic primacy and civilizing role in Europe.26 The message conveyed by “Tobia Futurista” is that the quest for “Italianness” justified participation in the Futurist movement and pervaded the artist’s subsequent changes in style, leading ultimately to the rejection of the avant-garde’s internationalism. The second part of “Tobia Futurista” includes Carrà reiteration of the distinctiveness of the Italian artistic tradition, characterized by the so-called senso costruttivo (architectural sense), which the character of Tobia has been pursuing in his art, despite being accused of going to Paris to get “models, as tailors do with clothes.”27 In opposition to this accusation, Tobia rejects any artistic cosmopolitanism, thus rebuffing the avant-garde internationalism of the prewar years as well as French Impressionism, to focus on developing a national art.

Another piece by Carrà for La Raccolta, “Dedicatoria ai giovani” (Dedicated to the Young), published in the August–October 1918 issue, makes an appeal for “discretion;” attributes prominence to craftsmanship; and states that “art is not a cheap and disposable commodity,” thus highlighting a rethinking of the artistic activity in terms of an intrinsically ethical commitment to form and technique.28

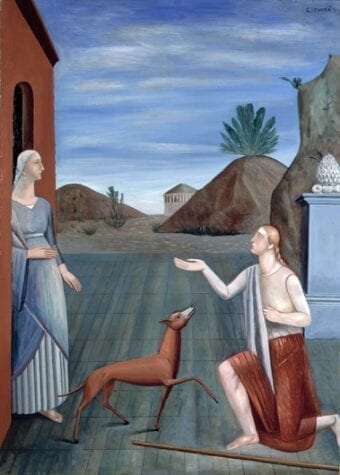

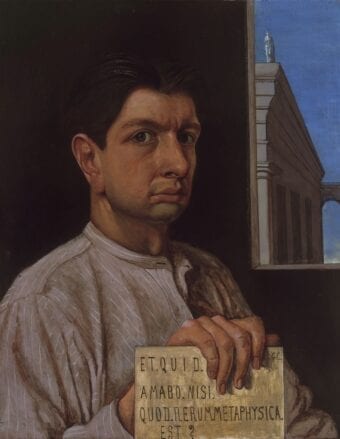

Carrà explored the concept of artistic “Italianness,” delving into some of its aesthetic and ideological implications, in a series of articles written between 1919 and 1922 for Mario Broglio’s influential art magazine Valori plastici (figure 7). The writings develop his idea of artistic renewal as an attempt to go beyond the achievements of the avant-garde while retaining part of its experience, and to revisit the Italian tradition as a legacy to be both cherished and renewed. Published in Rome between 1919 and 1922, Valori plastici proved to be one of the most significant Italian art magazines of the interwar years and the main vehicle for the theorization of Metaphysical art.29 It hosted a substantial number of articles by Carrà, de Chirico, and the latter’s brother, Alberto Savinio, as well as publishing numerous illustrations of Carrà’s and de Chirico’s works, including Carrà’s L’ovale delle apparizioni (The Oval of Apparitions, 1918), Il cavaliere occidentale (Western Horseman, 1917), Il figlio del costruttore (The Builder’s Son, 1918), La figlia dell’ovest (The Girl from the West, 1919), La camera incantata (The Enchanted Chamber, 1917), and Le figlie di Lot (The Daughters of Lot, 1919; figure 8). The first issue of 1921 featured almost exclusively illustrations by Carrà, among them earlier works, such as La carrozzella; works from the Metaphysical period, such as L’idolo ermafrodito, La musa metafisica, and Madre e figlio; and more recent drawings, dated 1919 and 1920. The magazine also published de Chirico’s Il grande metafisico (The Great Metaphysician, 1918), Natura morta autunnale (Autumnal Still Life, 1917), two versions of Il figliol prodigo (The Prodigal Son, 1917 and 1920), La signorina amata (The Beloved Young Lady, 1920), Il condottiero (The Commander, 1918), La sposa fedele (The Faithful Bride, 1918), Interno metafisico (Metaphysical Interior, 1918), Consolazioni metafisiche (Metaphysical Consolation, 1918), La vergine del tempo (The Virgin of Time, 1920), Natura morta evangelica (Evangelical Still Life, 1918), and I pesci sacri (The Sacred Fish, 1919), as well as the famous 1920 self-portrait (figure 9) of the artist holding the inscription “Et quid amabo nisi quod rerum metaphysica est?” (And what will I love if not the metaphysics of things?).

Both de Chirico’s and Carrà’s illustrations and writings for Valori plastici trace the painters’ divergence from the Metaphysical idiom to the pursuit of different artistic paths in the immediate postwar years, as well as their responses to some of the artistic debates at the time. As Paolo Fossati rightly notes in his seminal study on the magazine, Valori plastici was, to an extent, late with respect to the development of Metaphysical art as conceptualized by de Chirico and Carrà during their stay at the Villa Seminario.30 In his articles for the periodical, Carrà expressed a growing concern with identifying a transhistorical concept of artistic “Italianness,” which could be applied to contemporary art without running the risk of looking at the past with an “archaeological” gaze. The first piece he wrote for Valori plastici, for its first issue, was the poetic prose piece “Il quadrante dello spirito” (The Quadrant of the Spirit, 1918) – an almost ekphrastic text that was published with an illustration of his 1918 painting L’ovale delle apparizioni (figure 10) – in which Carrà summarized his attempt to go beyond naturalism and convey a sense of spirituality in art by apprehending the “hidden depth of ordinary things.”31 “Il quadrante dello spirito” poetically evokes the objects that appear in L’ovale delle apparizioni: the “metaphysical house of the Milanese proletarians;” an “electric man” shaped as an “hourglass” and made of “polychrome tin;” an “archaic statue” of a child holding a racket and a tennis ball, a memorial stone at the back; and an “enormous copper fish laid on two metal bars,” “motionless and ghostlike.”32 The exegetic thrust of the prose with respect to L’ovale delle apparizioni is still conceptually linked to the Metaphysical idea of capturing the enigma contained within the appearance of ordinary objects. However, Carrà departed from de Chirico by replacing the enigmatic juxtaposition of objects and historical references found in de Chirico’s works with a sense of spiritual and historical rootedness that the geometrical solidity of the forms depicted was intended to convey. The memorial associations that the objects evoke were not meant to be estranging; rather, they were conceived as epiphanies of the history and artistic tradition intrinsic in their forms.

It was this concept of the artistic tradition inherent in form that underpinned Carrà’s essay “L’italianismo artistico” (Artistic Italianism), published in May 1919, in which his idea of an Italian principle in art is foregrounded, embedded in the tradition of the nation, to be retrieved and nurtured with the aim of re-establishing the primacy of Italian art in Europe. Such a principle would achieve “extreme simplicity with a maximum of magnificence” and consisted of “a rule of coordination of the visual reality, without which a painting is nothing but a naturalistic fragment, unsuccessfully aspiring to a unifying center.”33 Carrà expressed the hope that Italian art would soon “go back to influencing the customs and spirit of the West, thereby fulfilling the spiritual needs of the present in the same way it did in ancient times.”34 The idea of the primacy of Italy in the postwar renewal of European art he further explored in the essay “Il rinnovamento della pittura in Italia” (The Renewal of Painting in Italy), published in Valori plastici in four parts between December 1919 and June 1920 (further sections were envisioned, but not published). The series of articles presented the character of classicità – described as orderly composition and balanced volumes – as particularly congenial to Italy, and they advocated for an Italian art intellectually independent, original, and free from foreign influence; based on discipline, knowledge, and experience; and developed in spiritual affinity with national tradition.35

Carrà’s reconnection with the Italian artistic tradition continued in an essay on Antonio Canova and Neoclassicism, published in Valori plastici in three parts between 1920 and 1921. He justified his choice to reassess Canova as an attempt to dispel the myth that his art was quintessentially academic,36 and he read the art of Neoclassicists such as Anton Raphael Mengs, Pompeo Batoni, Jacques-Louis David, and Canova himself as a reminder that “art is discipline, serenity, and composure.”37 Carrà did not analyze Canova’s work stylistically; instead, he focused on the sculptor’s biography, presenting him as an example of “civic austerity” and “Italianness” for refusing to serve any public duties under Napoleon, thus establishing a parallel between artistic style and political and ethical choices.38 Classicism was therefore distanced from academic associations and reconfigured as a politically charged artistic idiom that could be mobilized in terms of identity and as a way of reading national history. In his pursuit of the Italian principle, Carrà retained the idea that a critical judgement of art was indistinguishable from historical knowledge. He thus posited a close relation between history and culture at the center of a reading of art seen as the expression and interpretation of the social and political history of the nation.39

Giorgio de Chirico: From Metaphysical Art to Classicism

In de Chirico’s writings published between 1918 and 1922, a shift can be identified from a focus on the principles of Metaphysical painting to a broader reflection on the notion of classicism, intended particularly as craft and technique. This marked the artist’s engagement with current debates on the “return to order” and placed an emphasis on his personal interpretation of the artistic canon. While until 1918 his artistic idiom was largely still adherent to the Metaphysical principle, with incursions into portraiture from 1918, in 1919 he started producing works inspired by Renaissance art, including Il ritorno del figliol prodigo (The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1919), Diana (o Vestale) and Autoritratto con busto antico e pennello (Self-portrait with Ancient Bust and Paintbrush, 1919). As of 1920, his works became markedly classicist, with overt references to Renaissance painting, classical imagery, and evocations of Greek themes and landscapes. Il saluto degli argonauti partenti (The Departing Argonauts’ Farewell, 1920) and Mercurio e i metafisici (Mercury and the Metaphysicists, 1920) are examples of this new trajectory.40 The term “metaphysical” would continue to appear in his essays to connote a transhistorical, denaturalizing quality, which translated into a dehistoricized notion of classicism, mostly removed from national (and nationalistic) associations.

As with Carrà, Valori plastici was a fundamental outlet for de Chirico’s writings in the immediate postwar years, although he also wrote a number of significant essays for the magazines La Ronda, Il primato artistico italiano, and Il Convegno. In the first issue of Valori plastici, de Chirico published the visionary prose fragment “Zeusi l’esploratore” (Zeuxis the explorer). The piece is located and dated Rome, April 1918: it had initially been rejected by Raimondi for La Raccolta and was subsequently accepted by Broglio for Valori plastici.41 It contains de Chirico’s reconfiguration of himself as a twentieth-century incarnation of the Greek painter Zeuxis (renowned for his realism, stylistic innovation, and mastery of technique), bypassing Roman classicism and the Renaissance and reconnecting to a primeval Mediterranean culture symbolized by ancient Greece and Southern Italy. De Chirico filled the piece with Metaphysical imagery, suggestive of the artist’s journey into new artistic lands transformed by the Metaphysical eye, from the zinc glove hanging from a shop door, to the papier-mâché head in a hairdresser’s window, to the open window revealing “the mysteries of the street.”42 De Chirico positioned himself at the center of a Heraclitean vision of the world as inhabited by demons, which the artist had to uncover:

One needs to discover the demon in everything.

That’s what I was thinking in Paris in the years before the war.

Around me the international gang of modern painters stupidly scrambling around amongst overused formulas and sterile systems.

Only I, in my squalid studio in the Rue Campagne-Première, was beginning to see the first ghosts of an art that was more complete, more profound, more complex, and to use one word that would give a biliary colic to French critics: more metaphysical.43

This critique of contemporary French art was reminiscent of another 1918 essay by him, which argued that “the profound intention of a Cubist painter is not intrinsically different from that of any traditional painter, past, present, or future. […] The new metaphysical painting […] is free from any constraint and opens the way to the newest forms of lyricism, maintaining, formally, that strict and solid composition which is the unflagging mark of a really lasting work.”44

“Zeusi l’esploratore” was followed by a more programmatic article, “Sull’arte metafisica” (On Metaphysical Art), published in the April–May 1919 issue of Valori plastici, which elucidated the principles of Metaphysical painting. Everything, according to the artist, has two aspects: “a current one, which we always see and that people in general see, and another one, spectral or metaphysical, which only rare individuals can see in moments of clairvoyance and metaphysical abstraction.”45 There are two forms of “solitude” contained in a work of art: “one, which could be called ‘plastic solitude,’ which is that contemplative beatitude which is given to us by the ingenious construction and combination of the forms; the second solitude is the solitude of the signs: an eminently metaphysical solitude, from which any logical possibility of a visual or psychic education is a priori excluded.”46 This same article articulates the significance of the urban element in Metaphysical aesthetics. De Chirico identified the foundations of Metaphysical art in the “construction of cities, the architectural shape of houses, squares, gardens, ports, train stations,” and proclaims the “joys” and “sorrows” “enclosed in a colonnade, the corner of a street, a room, the surface of a table, the sides of a box. […] The minutely accurate and carefully considered use of surfaces and volumes constitutes the canon of metaphysical aesthetics.”47 De Chirico returned to the significance of the framing of space in his article “Il senso architettonico nella pittura antica” (The Architectural Sense in Ancient Painting), published in Valori plastici in June 1920, a reflection on the meaning of the architectural elements that enclose portions of the landscape in the works of such painters as Giotto and Perugino: using walls, colonnades, and windows, these artists isolated areas of space, creating a sense of foreboding, mystery, and drama.48

The essays defining the aesthetics of Metaphysical art were followed by a reworking of the idea of the classical and the rethinking of the artist’s personal relationship with pictorial tradition.49 “Il ritorno al mestiere” (The Return to Craft), the first of these articles, was published in Valori plastici in December 1919, and called for a return to highly skilled painting through the recovery of traditional techniques of draughtsmanship, acquired by copying past masters, and the care for painting materials, including making one’s own paint and grinding colors. De Chirico was highly critical of Secessionism, Fauvism, and Futurism, and dismissive of the interpretation that the latter had “liberated” art. The article concluded with his famous declaration “pictor classicus sum,”50 underscoring the notion of classicism as based on craftsmanship and assiduous technique that became central to de Chirico’s reflections in the immediate postwar years. By condemning Futurism as an unnecessary event in Italian art that had contributed to its decadence (he declared that “Futurism was necessary to Italy as much as the war was; it happened, like war […] but we could have done without it”51), de Chirico participated in the general reassessment and historicization of the movement within the post-avant-garde atmosphere of the “return to order,” which continued throughout the 1920s and interpreted Futurism as a move away and an aberration with respect to the Italian artistic tradition.

He further elaborated his interpretation of the classical in the article “Classicismo pittorico” (Pictorial classicism), published in the Roman magazine La Ronda in July 1920, which defined classicism as the ability handed down from the Greeks to create an essential and synthetic art capable of capturing the inner essence of objects through skillful draughtsmanship. Classicism was thus removed from any historical periodization and described instead as characterized, in all its manifestations, by “the subtlety and purity of the linear sensation” and “the complete absence of any sense of the gigantic and the voluminous.” It was obtained by “trimming and pruning,” reducing a phenomenon to “its skeleton, its sign, the symbol of its inexplicable existence.”52 The “linear demon” of Greek classicism, de Chirico argued, was found equally in the Quattrocento painters, for instance Botticelli and Ghirlandaio, and in artists such as Michelangelo, Albrecht Dürer, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and, later, Giovanni Segantini and Gaetano Previati.

The last article de Chirico wrote for Valori plastici, in 1921, he titled “La mania del Seicento” (The Obsession with the Seventeenth Century”), and it was a synthesis of the themes he had been exploring in his writings. As a polemical intervention against the current interest in seventeenth-century painting, the article argued that the Seicento marked the beginning of the decadence of modern art, paving the way to realism and the use of facile techniques such as oil painting, the habit of working on canvas, and the use of chiaroscuro. According to de Chirico, it was not possible to reclaim the art of the Seicento as part of the Italian tradition, because it lacked true “Italian” spirit. This was to be found instead in the painting of the Quattrocento, which exemplified “clear and solid painting, in which figures and objects appear as though washed, purified, and shining with inner light. A phenomenon of metaphysical beauty, which has something spring-like and autumnal at the same time.”53

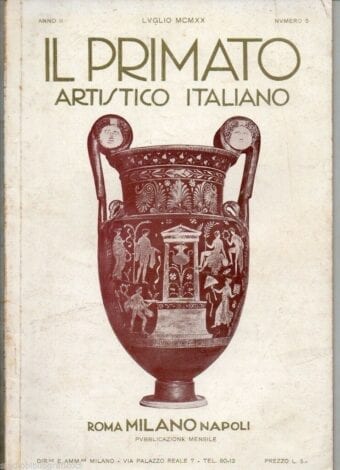

Between 1920 and 1921, de Chirico contributed articles also to the Milanese periodicals Il primato artistico italiano and Il Convegno. The former, edited by Guido Podrecca, was published in Milan (with branches in Rome and Naples) between 1919 and 1922 (figure 11). Subtitled Rivista di tutte le arti, the magazine published articles on literature, theater, visual art, music, and architecture, and hosted an array of high-profile contributors, including also Savinio, Carrà, Filippo de Pisis, Giovanni Muzio, Margherita Sarfatti, and Massimo Bontempelli. The intention of the periodical was to promote Italian culture in all its past and present manifestations and to reiterate its artistic primacy. In his articles for Il primato artistico italiano, de Chirico pursued some of themes developed in his Valori plastici essays. His first article for Il primato artistico italiano, “Le scuole di pittura presso gli antichi” (Painting Schools in Ancient Times), resumed his argument on craftsmanship already presented in “Il ritorno al mestiere” and lamented the extinction of painting schools and workshops where apprentices and pupils learned the craft of painting from a young age, and where close relationships and exchanges were formed between masters and disciples. Italy was indicated as the most suitable country to lead in the return to such art schools.54 He then published a series of “Considerations on Modern Painting” – surveys of contemporary national and international art. Initially they criticized the decadence of contemporary Italian painting caused by pedestrian imitation of French art, from Gustave Courbet to Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse, and argued in favor of nineteenth-century German painting and Milanese Neoclassicism.55 Next, they offered a reappraisal of Giuliano Traballesi, Andrea Appiani, Luigi Sabatelli, Francesco Hayez, and Giovanni Carnevali based on the claim that these Neoclassical painters were influenced by Milan’s architectural layout and location on flat land, and by the sense of calm and balance emanating from the city’s walls, squares, and monuments.56 The third survey by de Chirico returned to German painting, reviewing the work of German artists Hans Thoma and Adolph Menzel, and praising them for their “sense of adventure” – that is, their ability to go beyond realism and invest the reality represented with a sense of surprise and discovery.57

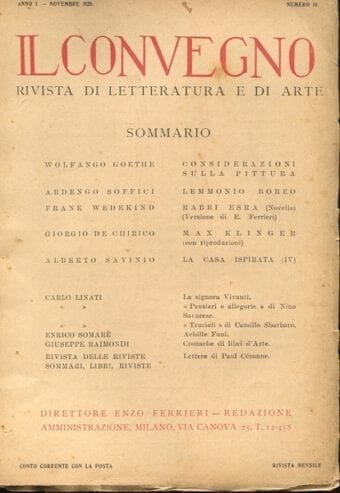

Il Convegno, for which de Chirico started writing in 1920, was founded in Milan that same year under the editorship of Enzo Ferrieri (figure 12). It was an eclectic magazine, with an interest in literature, music, theater, and the decorative arts as well as painting. Among its contributors in the first years of publication were Savinio, Raimondi, Carlo Linati, Cesare Angelini, Emilio Cecchi, Luigi Pirandello, Alfredo Panzini, and Federigo Tozzi. It had an interest in international culture, and published translations of James Joyce’s 1918 play Exiles and of writings by international authors including J. M. Synge, Miguel de Unamuno, and Thomas Mann, as well as reviews of contemporary foreign literature and art. The art section featured articles by de Chirico, Carrà, Soffici, Matteo Marangoni, and Enrico Somaré.58

For Il Convegno, de Chirico wrote monographic articles on Auguste Rénoir and Paul Gauguin, situating the former within a naturalist practice steeped in both the Italian Renaissance and the Flemish traditions of attention to draughtsmanship, form, and volume (although he criticized Rénoir’s later work as too influenced by Impressionism).59 In Gauguin he criticized the lack of formal training and his “terror” of beauty, though he acknowledged his sharp intelligence and appreciated qualities of his Tahitian paintings.60 De Chirico also embarked on a reassessment of artists who had influenced his art, proposing a personal genealogy and reconfigured tradition, unanchored from established temporalities and places, which was both transnational and transhistorical; and he offered a reflection on and redefinition of classicism along re-established lines, which intersected with his theorization of Metaphysical painting. He devoted an article to Raphael, noting how he conveyed an impression of “solidity,” giving the viewer a sense of “deeply spiritual well-being, a consolatory rhythm, as if we found ourselves in a room that had a perfect architecture, with big rectangular windows, placed high on the wall, so that one cannot see a corner of nature or buildings, but only solid sky, and the sounds of life are confused and far away.”61 Through architectural simile, de Chirico emphasized the transcendental quality of geometrical symmetry, which excluded, to an extent, the human element and proposed a reconfiguration of figurative priorities, whereby man was removed from the center of ontological investigation. This had already been developed by de Chirico both in his Metaphysical paintings of the war years, in which the human figure was reconfigured as a mannequin or a composite of geometrical elements, and in his theoretical writings, particularly those published in Valori plastici. De Chirico observed that in Raphael’s portraits, “there is something stable, immobile and twisted, which makes you think about the eternity of matter. The painted image appears as though it had been there before the painter created it.”62 He argued that all traces of life appear to have been removed from Raphael’s human figures, so that they look like motionless statues, invested with a “serene and disquieting look,” “as if they were images containing the secrets of sleep and death.”63

In the following issue of Il Convegno, de Chirico analyzed the paintings of Swiss artist Arnold Böcklin, whose work he had encountered during his stay in Munich between 1906 and 1909.64 In writing on Böcklin, de Chirico took the opportunity to expound his interpretation of the German master and his influence on his own painting. He set out to dispel the common misconception that Böcklin was a failed painter, a judgement voiced by influential critics such as Remy de Gourmont and recently reiterated by Soffici in his magazine Rete mediterranea.65 De Chirico argued that far from being the art of a failed master, Böcklin’s style was the result of a long elaboration of his craft, based on the study of nature and of ancient art. His “metaphysical” quality was based on the complete clarity and sharpness of his outlines, for his figures were never enveloped in mist and his edges never smoothed. For this reason, de Chirico considered him a “classical” painter – his classicism being conveyed in the clarity and realism of his figures, a solemnity of composition, the attention to detail, and the sense of “surprise” and “perturbation” that pervades his paintings, evoking earlier masters such as Paolo Uccello and Antonello da Messina.66 De Chirico recalled the strong impression he received the first time he saw a reproduction of a Böcklin painting, and the feeling of joy and emotion he still felt every time he saw one of his works, thus foregrounding the intertwining of memory, personal impressions, and nostalgia in the formation of his pictorial canon and the interpolation of these feelings into his elaboration of the idea of classicism.

For Il Convegno, de Chirico also wrote a substantial article on the German painter Max Klinger, another artist influential on his artistic development, on the occasion of his death in 1920. He attributed Klinger with a sense of “sweet and Mediterranean serenity,” a clear sense of reality and a lyrical and philosophical sentiment akin to that found in some Greek philosophers and poets, as well as an ability to combine scenes of contemporary life with “ancient visions,” thus obtaining a striking, dreamlike representation of reality. He defined Klinger as “the modern artist par excellence”: “Modern […] in the sense of a man aware of centuries of legacy in art and thought, someone who has a clear view of the past, the present and himself.”67 He ascribed to Klinger’s painting the undefined melancholy and nostalgia associated with the emblems of modern life: “[T]he breath of nostalgia that passes through the cities of Europe, through the crowded streets, the busy city centers, and the suburbs shaped by the geometry of the factories and workshops. […] It’s the nostalgia of train stations, of the arrivals and the departures; the melancholy of the ports, with liners setting sail on dark waters, all lit up.”68 De Chirico’s interpretation of nostalgia was not associated with the loss of an unrecoverable past, but rather with a sense of accumulation – of cultural detritus, almost – contained in the city and connected with the epistemological enigma and tragedy of modern life that envelops human beings. Klinger captured this feeling by freezing people “in the spectrality of a moment, amidst terribly real sets.”69

De Chirico returned to the question of the pictorial framing of space in “Riflessioni sulla pittura antica” (Reflections on Ancient Painting), published in the April–May 1921 issue of Il Convegno. The article notes how, in the works of Lombard and Tuscan Quattrocento painters, Venetian artists, German and Flemish painters, and French artists such as Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, the human figure is often represented against architectural details: columns, windows, doors, and architectural elements frame the space and create openings into new visions of the world, thus conferring semantic depth to a representation. The repeated architectural framing of space has, according to de Chirico, a “denaturalizing” effect. Equally, the acquaintance with the reproduction of statues allows a detachment from a naturalistic representation of the human figure. Architectural framing and its juxtaposition with natural elements creates antinaturalistic landscapes, open to resignification. De Chirico lamented the loss in modern painting of what he called the “architectural sense” – based in the framing of space through architectural details, strong tridimensional solidity of forms, and the extensive use of perspective – in pursuit of naturalism, and much to the detriment of technique.70

The only contemporary Italian artist considered by de Chirico in his articles for Il Convegno was the Ferrarese painter Gaetano Previati (1852–1920), whose work he had first seen in Milan in 1906.71 Previati’s visionary interpretation of the Divisionist technique had already inspired avant-garde artists including Umberto Boccioni, who, in a 1916 article for the Milanese magazine Gli Avvenimenti, had hailed Previati as a modern master whose painting should be considered as the last plastic expression of the Renaissance.72 On the occasion of his death in 1920 and in the years that followed, Previati enjoyed further recognition, particularly in Milanese post-avant-garde circles.73 In his article, de Chirico removed Previati from any correlation with fin de siècle aestheticism, instead likening his use of monochromatism to ancient frescos and equating his style with medieval art. He attributed to the painter a “spectral quality” that invested his works with a “nightmarish” character, created by an antinaturalistic style and a sense of spatial enclosure, as if the figures were surrounded by “prison walls.” The antinaturalism Previati invested in his figures, according to de Chirico, did not deprive them of spirituality, nor of the “metaphysics of the second aspect of nature, without which a work of art cannot be great.”74

As opposed to Carrà’s writings, which aimed to reclaim a close relationship between art, history, and national identity, de Chirico’s, in their reassessment both of the Italian tradition and of contemporary art, insisted on the technical aspect of the definition of classicism, thus configuring it as the reactivation of a timeless artistic language, handed down from Greek antiquity and identifiable transnationally across the centuries.75

Conclusion

Despite being characterized by eclecticism and, to an extent, ephemerality, periodicals such as La Brigata, La Raccolta, Valori plastici, Il primato artistico italiano, La Ronda, and Il Convegno were the centers of key modernist networks between 1916 and 1922; hosted some of the most significant artistic debates of the postwar years; and occupied a significant space in the Italian public sphere. They were important forums for the theorization of Metaphysical art and had an essential role in shaping the artistic debate in Italy in the years of the so-called “return to order.” They also played a fundamental role in the demise of avant-garde aesthetics in Italy, and in the revision of the relationship between art and politics, which saw a reconceptualization of the classical as central to the redefinition of postwar national culture. Carlo Carrà’s and Giorgio de Chirico’s writings during these crucial years not only clarify the Metaphysical artists’ different trajectories during and after the war, but also exemplify some of the aesthetic and ideological nuances of the elaboration of the classical in the postwar years, which reverberated, were appropriated, and ideologized in the 1920s and 1930s.

Bibliography

Anon. “Spezzatino.” La Brigata 1, no. 5 (1916): 120.

Baldacci, Paolo. De Chirico 1888–1919. La metafisica. Milan: Leonardo Arte, 1997.

Benzi, Fabio. Giorgio de Chirico. La vita e l’opera. Milan: La Nave di Teseo, 2019.

Binazzi, Bino. “Promessa.” La Brigata 1, no. 1 (1916): 1.

Bru, Sascha. “Italy: Introduction.” In The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, vol. 3, Europe 1880–1940, part 1, edited by Peter Brooker, Sascha Bru, Andrew Thacker, and Christian Weikop, 439–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Bruera, Franca. “Du mythe de Paris au myth d’Apollinaire.” In Amis européens d’Apollinaire, edited by Michel Décaudin, 103–23. Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, 1995.

Carrà, Carlo. “Canova e il neoclassicismo.” Valori plastici 2, nos. 9–12 (1920): 93–95.

Carrà, Carlo. “Canova e il neoclassicismo (II).” Valori plastici 3, no. 1 (1921): 1–5.

Carrà, Carlo. “Canova e il neoclassicismo (III).” Valori plastici 3, no. 2 (1921): 30–35.

Carrà, Carlo. “Dedicatoria ai giovani.” La Raccolta, nos. 6–8 (1918): 81–84.

Carrà, Carlo. “Il quadrante dello spirito.” Valori plastici 1, no. 1 (1918): 1–2.

Carrà, Carlo. “Il rinnovamento della pittura in Italia. Parte III.” Valori plastici 2, nos. 3–4 (1920): 33–36.

Carrà, Carlo. “Il ritorno di Tobia.” La Raccolta 1, no. 1 (1918): 1–3.

Carrà, Carlo. “L’italianismo artistico.” Valori plastici 1, nos. 4–5 (1919): 1–5.

Carrà, Carlo. “Tobia futurista.” La Raccolta 1, no. 2 (1918): 24–27.

Carrà, Carlo. “Tobia futurista.” La Raccolta 1, no. 4 (1918): 60–62.

Carrà, Carlo. Tutti gli scritti. Edited by Massimo Carrà. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1978.

Carrà, Carlo, and Ardengo Soffici. Lettere 1913–1919. Edited by Massimo Carrà and Vittorio Fagone. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1983.

Carrà, Massimo, Ester Coen, and Gérard-Georges Lemaire. Carlo Carrà. Florence: Giunti, 1987.

Carrà, Massimo, Elena Pontiggia, and Alberto Fiz. Carlo Carrà. Il realismo lirico degli anni venti. Milan: Mazzotta, 2002.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Arnoldo Böcklin.” Il Convegno 1, no. 4 (1920): 47–53.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Augusto Renoir.” Il Convegno 1, no. 1 (1920): 36–46.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Classicismo pittorico.” La Ronda 2, no. 7 (1920): 50–55.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Considerazioni sulla pittura moderna.” Il primato artistico italiano 2, no. 5 (1920): 15–16.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Considerazioni sulla pittura. Parte II. I neoclassici milanesi.” Il primato artistico italiano, 2, no.7 (1920): 17–21.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Considerazioni sulla pittura. Parte III. Hans Thoma e Adolfo Menzel.” Il primato artistico italiano 3, nos. 4–5 (1921): 60–64.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Gaetano Previati.” Il Convegno 1, no. 7 (1920): 29–36.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Il ritorno al mestiere.” Valori plastici 1, nos. 11–12 (1919): 15–19.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Il senso architettonico nella pittura antica.” Valori plastici 2, nos. 5–6 (1920): 59–61.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “La mania del seicento.” Valori plastici 3, no. 3 (1921): 60–62.

De Chirico, Giorgio. Lettere 1909–1929. Edited by Elena Pontiggia. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2018.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Le scuole di pittura presso gli antichi.” Il primato artistico italiano 2, nos. 2–3 (1920): 26–27.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Max Klinger.” Il Convegno 1, no. 10 (1920): 32–44.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Paolo Gauguin.” Il Convegno 1, no. 2 (1920): 53–59.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Raffaello Sanzio.” Il Convegno 1, no. 3 (1920): 53–63.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Riflessioni sulla pittura antica.” Il Convegno 2, nos. 4–5 (1921): 201–06.

De Chirico, Giorgio. Scritti/1 1911–1945. Edited by Andrea Cortellessa. Milan: Bompiani, 2008.

De Chirico, Giorgio. “Zeusi l’esploratore.” Valori plastici 1, no. 1 (1918): 10.

De Grazia, Victoria. How Fascism Ruled Women. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Fagiolo Dell’Arco, Maurizio. L’opera completa di Giorgio De Chirico 1908–1924. Milan: Rizzoli, 1984.

Ferris, David. Silent Urns: Romanticism, Hellenism, Modernity. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Fiorillo, Ada Patrizia. “Ferrara nei venti della modernità. Il dibattito artistico nei primi decenni del XX secolo.” Annali online di Ferrara, no. 1 (2012): 220-240.

Fossati, Paolo. “Valori plastici” 1918–1922. Turin: Einaudi, 1981.

Langella, Giuseppe. Il secolo delle riviste. Lo statuto letterario dal “Baretti” a “Primato.” Milan: Vita e Pensiero, 1982.

Pontiggia, Elena, and Mario Quesada, eds. L’idea del classico 1916–1932. Temi classici nell’arte italiana degli anni Venti. Milan: Fabbri, 1992.

Roversi, Lorenza, ed. Il ritorno al mestiere. “La Raccolta,” Giuseppe Raimondi e gli artisti della metafisica ferrarese. Ferrara: Fondazione Ferrara Arte, 2018.

Stella, Angelo, ed. “Il Convegno” di Enzo Ferrieri e la cultura europea dal 1920 al 1940. Pavia: Università degli Studi di Pavia, 1991.

Storchi, Simona. “Valori Plastici 1918–1922. Le inquietudini del nuovo classico,” The Italianist 26 (2006): supplement.

Tedeschi, Francesco. Il futurismo nelle arti figurative (dalle origini divisioniste al 1916). Milan: Pubblicazioni dell’I.S.U Università Cattolica, 1995.

How to cite

Simona Storchi, “Metaphysical Writing and the ‘Return to Order’: Artistic Theorization and Modernist Magazines Between 1916 and 1922,” in Erica Bernardi, Antonio David Fiore, Caterina Caputo, and Carlotta Castellani (eds.), Metaphysical Masterpieces 1916–1920: Morandi, Sironi, and Carrà, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 4 (July 2020), accessed [insert date].

- Sascha Bru, “Italy: Introduction,” in The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, vol. 3, Europe 1880–1940, part 1, ed. Peter Brooker, Sascha Bru, Andrew Thacker, and Christian Weikop (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 439.

- Giuseppe Langella, Il secolo delle riviste. Lo statuto letterario dal “Baretti” a “Primato” (Milan: Vita e Pensiero, 1982).

- Victoria De Grazia, How Fascism Ruled Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 251.

- Langella, Il secolo delle riviste, 3–7.

- Bru, “Italy: Introduction,” 441.

- The correspondence between Giorgio de Chirico and the editors of the magazines Valori plastici and Il Convegno (Mario Broglio and Enzo Ferrieri, respectively) around 1920 is evidence of these financial anxieties, with de Chirico complaining to Broglio of the delayed payment of 300 lira for an article written by Savinio and two of his drawings, and the insistence with which he solicited payment by Ferrieri for his articles for Il Convegno. See Giorgio de Chirico, Lettere 1909–1929, ed. Elena Pontiggia (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2018), 269, 271 and 276.

- See the correspondence between de Chirico and Broglio in Giorgio de Chirico, Lettere 1909–1929, 277–78.

- A letter from de Chirico to Broglio dated November 19, 1921, lists L. 150 as the price for the work Vestale, the same amount claimed by the artist for an article for Valori plastici (see de Chirico, Lettere 1909–1929, 278).

- Carlo Carrà, “La mia vita,” in Tutti gli scritti, ed. Massimo Carrà (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1978), 690–91. Unless otherwise stated, all translations are the author’s.

- See Gérard-George Lemaire, “L’itinerario artistico di Carlo Carrà,” in Carlo Carrà, 18.

- See Carlo Carrà, “Parlata su Giotto,” (La Voce, March 31, 1916), “Le parentesi dell’io” (La Voce, April 30, 1916), and “Paolo Uccello costruttore” (La Voce, September 30, 1916), in Carrà, Tutti gli scritti, 63–80.

- Bino Binazzi (1878–1930) was a Tuscan poet and journalist close to the Florentine avant-garde circles and particularly associated with Giovanni Papini, Ardengo Soffici, and Aldo Palazzeschi. Poet and journalist Francesco Meriano (1896–1934) had a diplomatic career in the 1920s.

- See Lorenza Roversi, “‘La Raccolta’ tra nuova sensibilità letteraria e metafisica ferrarese,” in Il ritorno al mestiere. “La Raccolta,” Giuseppe Raimondi e gli artisti della metafisica ferrarese, ed. Lorenza Roversi (Ferrara: Fondazione Ferrara Arte, 2018), 19.

- Bino Binazzi, “Promessa,” La Brigata 1, no. 1 (1916): 1.

- Apollinaire contributed a poem titled “La Voyage du Kabyle” to La Brigata 1, no. 9 (1917): 200. On the relationship between Francesco Meriano and Apollinaire, see Franca Bruera, “Du mythe de Paris au myth d’Apollinaire,” in Amis européens d’Apollinaire, ed. Michel Décaudin (Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, 1995), 103–23.

- Anon., “Spezzatino,” La Brigata 1, no. 5 (1916): 120.

- La Brigata 2, no. 8 (1917): 178.

- See Giorgio de Chirico. Lettere 1909–1929, 119n.

- Only two further issues were published, in April 1918 and June 1919.

- Giuseppe Raimondi evokes the birth of La Raccolta in I tetti sulla città 1973–1976 (Milan: Mondadori, 1977), 98.

- Giuseppe Raimondi, “Terrazza. Valori Plastici,” La Raccolta 1, nos. 9–10 (1918): 120.

- Carlo Carrà, “Autopresentazione,” in Tutti gli scritti, 84.

- Published respectively in the March, April, and June 1918 issues of La Raccolta. The biblical theme of Tobias – who, while traveling with the archangel Raphael, caught a fish whose heart and liver could drive off evil spirits and whose gall healed his father Tobit’s blindness on his return home – already belonged to the pictorial tradition. It had been recently treated by de Chirico in his highly symbolic 1917 painting Il sogno di Tobia (Tobia’s Dream), which, according to Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arco, inspired Carrà’s paintings L’ovale delle apparizioni (The Oval of Apparitions, 1918) and Composizione TA (Composition TA, 1916–18). See Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arco, L’opera completa di Giorgio De Chirico 1908–1924 (Milan: Rizzoli, 1984), 100; and Paolo Baldacci, De Chirico 1888–1919. La metafisica (Milan: Leonardo Arte, 1997), 362.

- See Carrà, La mia vita, 703.

- See Massimo Carrà, Elena Pontiggia, and Alberto Fiz, Carlo Carrà. Il realismo lirico degli anni venti (Milan: Mazzotta, 2002), 23.

- Carlo Carrà, “Tobia futurista,” La Raccolta 1, no. 2 (1918): 25–26.

- Carlo Carrà, “Tobia futurista,” La Raccolta 1, no. 4 (1918): 62.

- Carlo Carrà, “Dedicatoria ai giovani,” La Raccolta 1, nos. 6–8 (1918): 81–84.

- See Paolo Fossati, “Valori Plastici” 1918–1922 (Turin: Einaudi, 1981); and Simona Storchi, “Valori Plastici 1918–1922. Le inquietudini del nuovo classico,” The Italianist 26 (2006): supplement.

- Fossati, “Valori plastici,” 5.

- Carlo Carrà, “Il quadrante dello spirito,” Valori plastici 1, no. 1 (1918): 1.

- Ibid., 1–2.

- Carlo Carrà, “L’italianismo artistico,” Valori plastici 1, nos. 4–5 (1919): 5.

- Ibid.

- See, in particular, Carlo Carrà, “Il rinnovamento della pittura in Italia. Parte III,” Valori plastici no. 2–4 (1920): 33–36.

- Carlo Carrà, “Canova e il neoclassicismo (III),” Valori plastici 3, no. 2 (1921): 30.

- Carlo Carrà, “Canova e il neoclassicismo,” Valori plastici 2, nos. 9–12 (1920): 95.

- Ibid., 32.

- David Ferris, Silent Urns: Romanticism, Hellenism, Modernity (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000), 27.

- See Benzi, Giorgio de Chirico, 231–52. See also Federica Rovati, “‘Pittura senza aggettivi’: tradizione italiana e metafisica negli anni di ‘Valori Plastici,’” in De Chirico a Ferrara: metafisica e avanguardia, ed. by Paolo Baldacci e Gerd Roos (Ferrara: Palazzo dei Diamanti and Fondazione Ferrara Arte, 2015), 143–51.

- See de Chirico, Lettere 1909–1929, 152.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Zeusi l’esploratore,” Valori plastici 1, no. 1 (1918): 10.

- Ibid.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “L’arte metafisica della mostra di Roma,” in Scritti/1 1911–1945, ed. Andrea Cortellessa (Milan: Bompiani, 2008), 661.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Sull’arte metafisica,” Valori plastici 1, nos. 4–5 (1919): 16.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 15–17.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Il senso architettonico nella pittura antica,” Valori plastici 2, nos. 4–5 (1920): 59–61.

- See Fabio Benzi, Giorgio de Chirico. La vita e l’opera (Milan: La Nave di Teseo, 2019), 223–24.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Il ritorno al mestiere,” Valori plastici 1, nos. 11–12 (1919): 15–19.

- Ibid., 19.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Classicismo pittorico,” La Ronda 2, nos. 7 (1920): 51.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “La mania del Seicento,” Valori plastici 3, nos. 3 (1921): 62.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Le scuole di pittura presso gli antichi,” Il primato artistico italiano 2, nos. 2–3 (1920): 26–27.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Considerazioni sulla pittura moderna,” Il primato artistico italiano 2, no. 5 (1920): 15–16.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Considerazioni sulla pittura. Parte II. I neoclassici milanesi,” Il primato artistico italiano 2, no. 7 (1920): 17–21.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Considerazioni sulla pittura. Parte III. Hans Thoma e Adolfo Menzel,” Il primato artistico italiano 3, nos. 4–5 (1921): 60–64.

- See Angelo Stella, ed., “Il Convegno” di Enzo Ferrieri e la cultura europea dal 1920 al 1940 (Pavia: Università degli Studi di Pavia, 1991).

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Augusto Renoir,” Il Convegno 1, no. 1 (1920): 36–46.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Paolo Gauguin,” Il Convegno 1, no. 2 (1920): 53–59. From the correspondence between de Chirico and Ferrieri, it is possible to evince that de Chirico’s critique of Gauguin had not entirely met with Ferrieri’s approval and that the article had been cut or amended. See de Chirico, Lettere, 271.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Raffaello Sanzio,” Il Convegno 1, no. 3 (1920), 53.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 54.

- Baldacci, De Chirico 1888–1919, 35–38.

- Ardengo Soffici, “Preraffaellismo,” in Rete mediterranea, no. 1 (1920): 71–78.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Arnoldo Böcklin,” Il Convegno 1, no. 4 (1920): 50.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Max Klinger,” Il Convegno 1, no. 10 (1920): 44.

- Ibid., 38–39.

- Ibid., 40.

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Riflessioni sulla pittura antica,” Il Convegno, nos. 4–5 (1921): 201–06.

- Baldacci, De Chirico 1888–1919, 34.

- See Ada Patrizia Fiorillo, “Ferrara nei venti della modernità. Il dibattito artistico nei primi decenni del XX secolo,” Annali online di Ferrara, no. 1 (2012): 220–40; Francesco Tedeschi, Il futurismo nelle arti figurative (dalle origini divisioniste al 1916) (Milan: Pubblicazioni dell’I.S.U Università Cattolica, 1995), 52.

- For instance, Enrico Somaré reassessed Previati’s work in his article “Gaetano Previati,” Il Primato artistico italiano, n. 5 (1920): 26-32; Ugo Ojetti included him in the second volume of his Ritratti di artisti italiani (Milan: Treves, 1923), and Margherita Sarfatti included a chapter on Previati in her 1925 volume Segni colori e luci (Bologna: Zanichelli, 1925). De Chirico himself wrote to Ferrieri after sending his article, saying that he had written it “with care and love” (letter to Enzo Ferrieri, August 19, 1920, in Pontiggia, Giorgio de Chirico. Lettere, 269).

- Giorgio de Chirico, “Gaetano Previati,” Il Convegno 1, no. 7 (1920): 34.

- See Elena Pontiggia, “L’idea del classico. Il dibattito sulla classicità in Italia 1916–1932,” in L’idea del classico 1916–1932. Temi classici nell’arte italiana degli anni Venti, ed. E. Pontiggia and Mario Quesada (Milan: Fabbri, 1992), 43.