Written by CIMA Fall 2020 Fellow, Claudia Daniotti.

Among the artworks featuring in the exhibition Marino Marini: Arcadian Nudes, two bronze reliefs are displayed side by side. Not only do they encapsulate perfectly the theme of the show, that is, the representation of the female body, but also exemplify a key feature in Marini’s artistic production: the tension between the art of the past and the art of the present, the dialogue underpinning his whole career between forms and gestures established by centuries of tradition and the more contemporary works showcased around him.

Fondazione Marino Marini

Fondazione Marino Marini

The two reliefs (Figs 1 and 2) were cast in 1943, at the beginning of the three-year period that Marini spent in Tenero, Switzerland, where he took refuge from the war that came to threat the city he had settled in, Milan. Little is known about the circumstances in which they were created; almost identical in size and similar in the compositional arrangement, they are known to us in several exemplars and different media, which remained largely in Marini’s possession until his death in 1980 (cfr. Marino Marini. Catalogo ragionato della scultura, ed. Giovanni Carandente, Milan 1998, p. 154, nos 213 and 214). Each relief shows the figures of three women, their bodies, either fully or completely naked, occupying the whole height of the bronze piece. The first relief discussed here (Fig. 1) is known as The Three Graces, a title which locates it firmly within the iconographic tradition concerning the mythical daughters of Zeus who, according to Homer, were part of the retinue of the goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite.

of a Hellenistic original, marble, Siena,

Cathedral, Piccolomini Library

While their names are differently recorded by the Greek poets, in antiquity the three Graces (or Charites) were regarded as personifications of beauty, grace, and joy, who played an attendant role, either serving as handmaidens of Aphrodite (more rarely, of Zeus’s wife Hera) or gracing festivals and organizing dances.

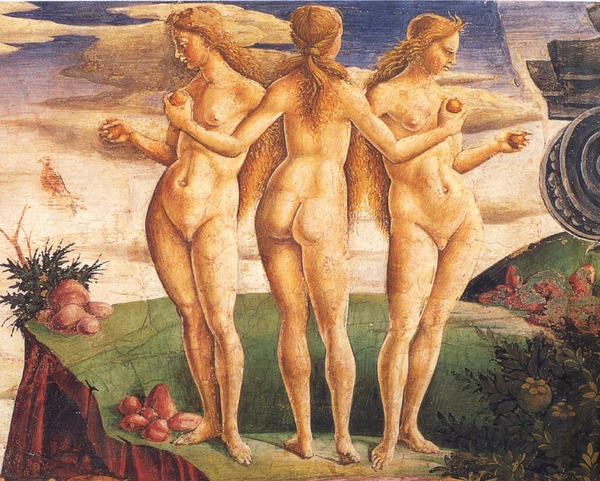

In keeping with their role, a visual tradition established in Greco-Roman art to represent them as a group of three beautiful young women dancing in the nude, joining hands or resting their arms on each other’s shoulders, so as to create a circular form suggesting their graceful movement. The canonical form for representing the Graces came into being between the second and the first century BC and is most famously exemplified by the statuary group which has been in the Piccolomini Library in the Siena Cathedral since the early sixteenth century (Fig. 3), with the central Grace turning her back to us and her two companions at either side facing the viewer.

Hever Castle, Kent

Salone dei Mesi

del Bargello

Museo del Prado

This iconographic composition, often referred to as ‘Siena Group pose’, was enormously influential and can be found in ancient Roman frescoes and sarcophagi (Figs 4 and 5), fifteenth-century paintings and medals (Figs 6 and 7) and the most famous works, among others, of Sandro Botticelli and Rubens (Figs 8 and 9).

As most famously documented by Antonio Canova, who explored the theme at length, both in sculpture and in painting (Figs 10 and 11), variations from the established canon are of course not rare, and tend to emphasise the idea of sophisticated elegance, gaiety and grace which are so central to Neoclassical art and culture.

1813-1816, marble, St Petersburg,

The State Hermitage Museum

ca. 1799, tempera on paper,

Possagno (Treviso), Gipsoteca Canoviana

When put in dialogue with this tradition, Marini’s take on what remains a standardized subject appears to be bolder than it may appear at first glance. His rearrangement of the traditional iconography by altering the postures of all the three Graces still allows to identify the ancient theme, which is not watered down to a generic depiction of three women or dancers.

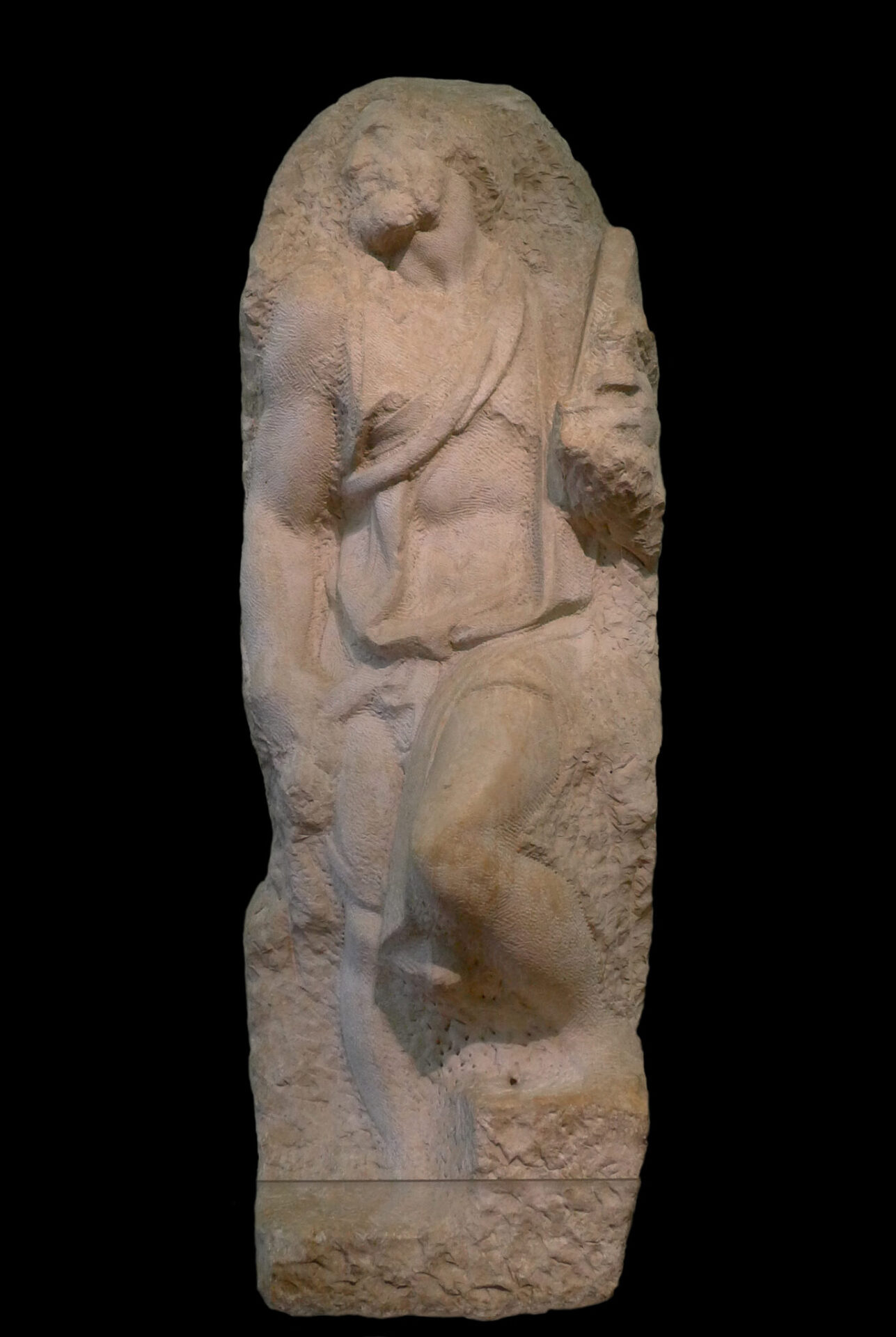

The Young Slave, ca. 1530, marble, Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia

Yet, the notable choice of turning the central Grace to face the viewer transforms the relief in a highly dramatic composition, where the emergence from the surface of her body features – her head, breasts, belly and especially her left leg – gives a remarkable dynamism to the composition, where no dance is performed and no movement can therefore be suggested as the traditional iconography had it. It is tempting to see in the Grace’s left knee projecting forward into our space an homage to Michelangelo, whose unfinished Young Slave intended for the tomb of Pope Julius II (Fig. 12) and the statue of St Matthew for Santa Maria del Fiore (Fig. 13) were certainly in Marini’s mind – not least because of their location in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, where Marini had received his artistic training, first as a painter and then as a sculptor.

St Matthew, 1505-1506, marble,

Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia

There is a distant echo of Michelangelo’s monumentality in a relief as little as Marini’s Three Graces: the plumpy volumes of the figures, the bodies filling up the whole space available, their heads and toes brushing the edges of the slab – everything conveys a sense of monumentality despite the reduced scale, not unlike what happens in other contemporary works by Marini such as the Small Nude (Fig. 14), also featuring in the CIMA exhibition.

As much as The Three Graces, the second bronze relief on show at CIMA (Fig. 2) has a rough, unpolished, almost expressionistic surface; yet, the three women who are seen towering in it couldn’t be more different from their three companions of classical descent. Once again, the title assigned to the work is key: this low-relief is known as Composition, a rather generic title suggesting that no precise subject exists – or at least, none could be identified. What is going on

in the picture is still a matter open to debate: the two women at the centre and on the left hand-side seem to be disrobing themselves, their vests given shape through a coarse treatment of the bronze and their gestures unwittingly reminiscent of visual formulae belonging to the goddesses who are caught disrobing in front of the viewer more often in the ancient myth – Aphrodite and Hera. The woman on the right-hand side has a fierce attitude in her standing as if on a doorstep while apparently lifting her tight chemise and so revealing the lower part of her body. There is one iconographic detail, however, that makes all the more clear that these women, unlike Marini’s Three Graces, are not reinventions from an antiquity long past, but rather they live firmly in Marini’s times: namely, they wear high heels (Fig. 15).

Marini’s references here are not to the classical past in which his art remains so firmly rooted, but rather to more contemporary depictions of the female body: not only the Bathers so iconically caught while disrobing themselves by the French Impressionists, but also the prostitutes whose world was so often excruciatingly analysed and even caricatured from the late nineteenth century. There is something in Marini’s Composition, as co-curator of the exhibition Laura Mattioli has noted, of Mario Sironi’s Venus of the Ports (Fig. 16), as well as the crude approach to the female universe underpinning the work of Expressionist artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Tempera and collage on paper on canvas,

Milan, Casa Museo Boschi di Stefano

The Three Graces and Composition were rightly displayed at CIMA as if they were a diptych, one next to the other. Nothing suggests that Marini had ever conceived them as one, but they can profitably be discussed one in relation to the other as eloquent examples of what meant to Marini, in the year 1943, to study once again the body of women: to appropriate, reinvent and even profoundly alter the ancient models that accompanied him throughout his career, and to find a new artistic language to portray the women of his own time, so far removed from the idealized, impossible models handed down by the tradition.

See a video here.