‘Bombs Against the Skyscrapers’: Depero’s Strange Love Affair with New York, 1928–1949

Raffaele Bedarida Raffaele Bedarida Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/depero/

This study compares the activities of Fortunato Depero in New York to his fictional account of them. Depero’s first stay in New York in 1928–1930 was far from successful: in the midst of the Wall Street crash and its aftermath, his paintings failed to sell and his commercial enterprise in the city, the Futurist House, did not survive longer than a couple of months. The artist, however, created a myth out of his experience when he went back to Italy. For more than ten years, he wrote extensively about his American experience and dedicated several works to New York, in a variety of mediums. These expressed extreme enthusiasm about the city, as well as antagonism and even anger against it. After the fall of Mussolini, Depero returned to the ‘New Babel’ for two more years (1947–1949), which, again, proved a fiasco. Paradoxically for a Futurist, he was ultimately happy to leave the metropolis for a bucolic retreat in the suburbs of Connecticut. Depero’s ambivalent love affair with New York was part of the changing debate on Americanism that took place in Italy during the 1930s and, then, in the reconstruction years after World War II. This was a major avenue for Italians to define and re-define their own modernity, and Depero – in his idiosyncratic way – played a central part in this pursuit.

Introduction

Italian Futurist Fortunato Depero1 published two versions of his autobiography: Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita (Fortunato Depero in His Works and Life) was released in Italian in 1940; a revised version – which was substantially changed in content and structure – was published in English in 1947 as So I Think, So I Paint. In both, New York plays a central role. In Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita, the City of New York makes its first appearance in a description of the Macy’s 1929 Thanksgiving Parade (figure 1),

The most impressive and characteristic images of this commercial procession are the immense, swinging balloons … which represent human and animal figures. Flying elephants and lunar heads smile and float happily above the crowd… They seem to belong to a fabulous world made of huge soap bubbles.2

This passage closes the book’s section on advertising and introduces its more strictly autobiographical part, “Brani di vita vissuta” (Fragments of a Lived Life). Here, New York covers by far the largest portion: fifty out of eighty pages. Depero gave even more importance to New York in the English version of his book. Published when he was ready for his second endeavor across the Atlantic, the book intended to function as “a good and useful introduction ticket” and to refresh New Yorkers’ memory about him (with some retouches),3

I went to New York in 1927 and stayed there till 1931. During this time I set up seven personal shows. The press took much notice both of my decorative art and of my painting [sic, more on this below]. The famous critic Christian Brinton introduced me to the public and to the most important newspapers. He also wrote the introduction to one of my catalogues in which, among other things, he says: “Depero created organic plastic dynamism transcending beyond specific groups and possessing a rhythmical vibration and an esthetic manner of its own.”4

The prominence given to New York in these texts is remarkable considering that Depero had spent a mere two years in the city; a full decade had passed since then (two decades by the time of the English edition); and, above all, those two years did not coincide at all with the peak of his career. On the contrary, Depero’s stay in New York was largely unsuccessful and signaled the beginning of the artist’s misfortune in Italy too. A second interesting point is that New York, as opposed to other cities he had resided, is presented in the book as a lived experience. Rome, Capri and Rovereto are contrastingly discussed indirectly, through Depero’s account of his artistic production in those cities.5

In this essay, I do not intend to focus so much on Depero’s activity in New York – which has been explored in detail in a number of publications during the past three decades6 – but rather on how his New York experience became prominent in his life and œuvre, starting from the artist’s own account of it, and why the fact that he attributed so much importance to New York is significant. In particular, this essay discusses the discrepancies between Depero’s activity in New York and his account of it. The process of myth-making that takes place in his reports is interesting for various reasons. On one level, it helps us to understand the artist’s strategy of self-promotion: a theorist and practitioner of ‘auto-réclame’ (or ‘personal branding,’ as we would call it today),7 Depero knew that his experience in New York was unique and valuable on the Italian art market. Secondly, Depero followed Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s lead when he trumpeted his alleged ‘triumphs in America,’ as this was part of a more general attempt to emphasize the Futurists’ success abroad and, in turn, put pressure on the Fascist government to accept Futurism as State art.8 Ultimately, Depero’s ambivalent love affair with New York, as elaborated through two decades of writings and artistic production, was part of the changing debate on Americanism in Italy during the 1930s and, later, in the reconstruction years after World War II. This was a major avenue for the Italians to define and re-define their own modernity, and Depero – in his idiosyncratic way – played a central part in it.

The First Journey to New York (1928–1930)

Depero had expressed his intention to move to New York as early as 1922, but it was only in 1928 that he was able to turn the idea into reality.9 Although he received encouragement from some industrialist clients, he met with deep skepticism from his artist friends.10 Marinetti especially tried to deter him. At that time, Paris was still considered the center of the international art world, and America was, at best, a profitable market. “I was told that there is no art in America”, Depero wrote.11 During his entire New York adventure, Depero regularly sent Marinetti reports on his activity. These often read like attempts to convince the revered capo del futurismo (head of Futurism) of the value of his American enterprise.

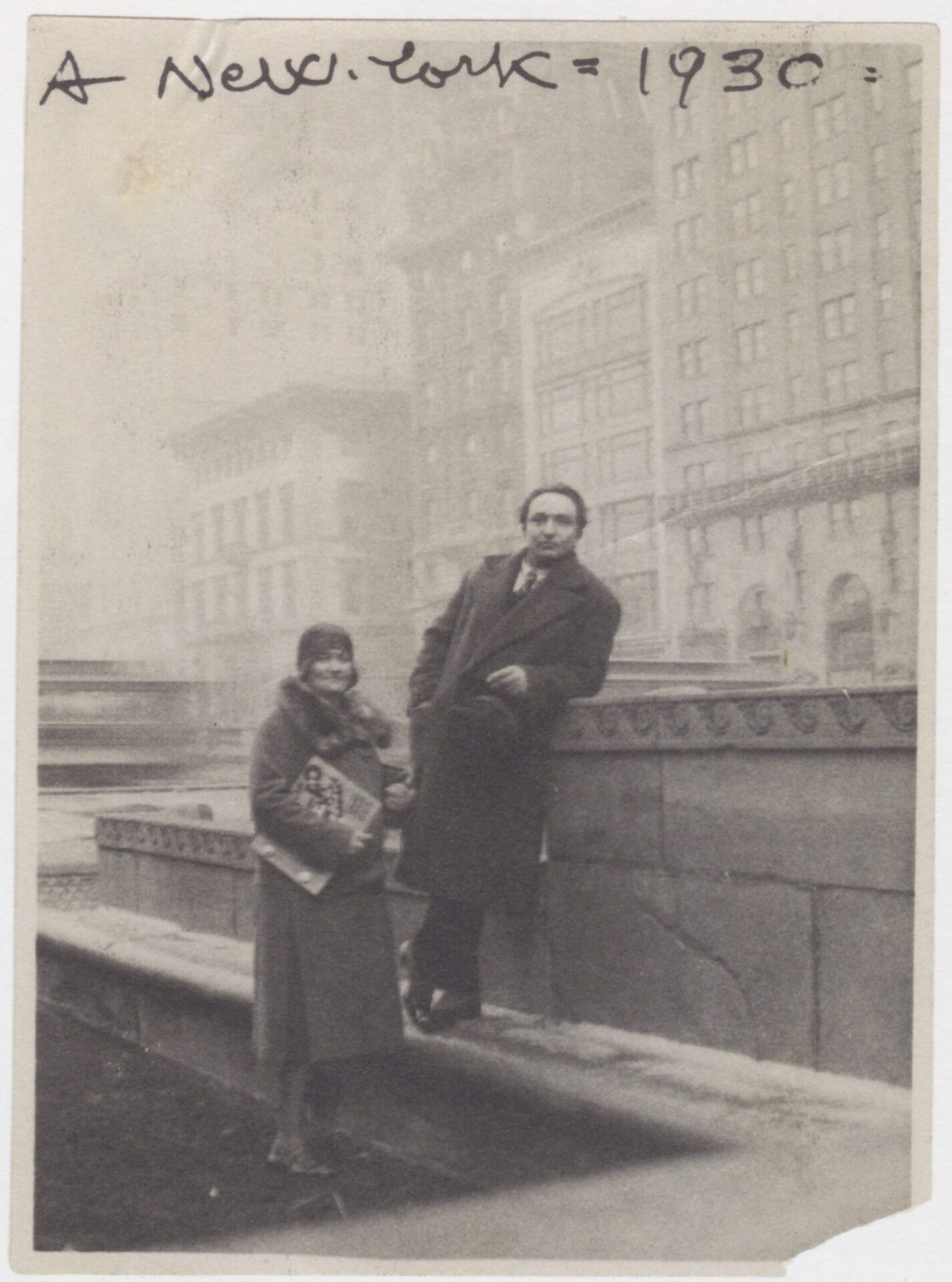

On October 2, 1928, while still traveling on the transatlantic liner Augustus, Depero wrote to Marinetti with typical optimism, “I will smash the Alps of the Atlantic, I will build machines made of light on top of the giant American parallelepipeds.”12 Everything looked promising to him. He arrived in the city with his wife Rosetta at his side and his recently completed ‘Bolted Book,’ Depero Futurista under his arm (figure 2). This landmark publication was a collection of his past achievements, as well as a showcase of his graphic abilities.13 Depero used it in New York as a portable museum and means of self-promotion; he donated to potential clients, and exhibited the book as both a whole and by individual, unbolted pages in the Exhibition of the Italian Book San Francisco Public Library in November 1929.14 He had also shipped 500 of his artworks, with which he hoped to conquer the American art market.15

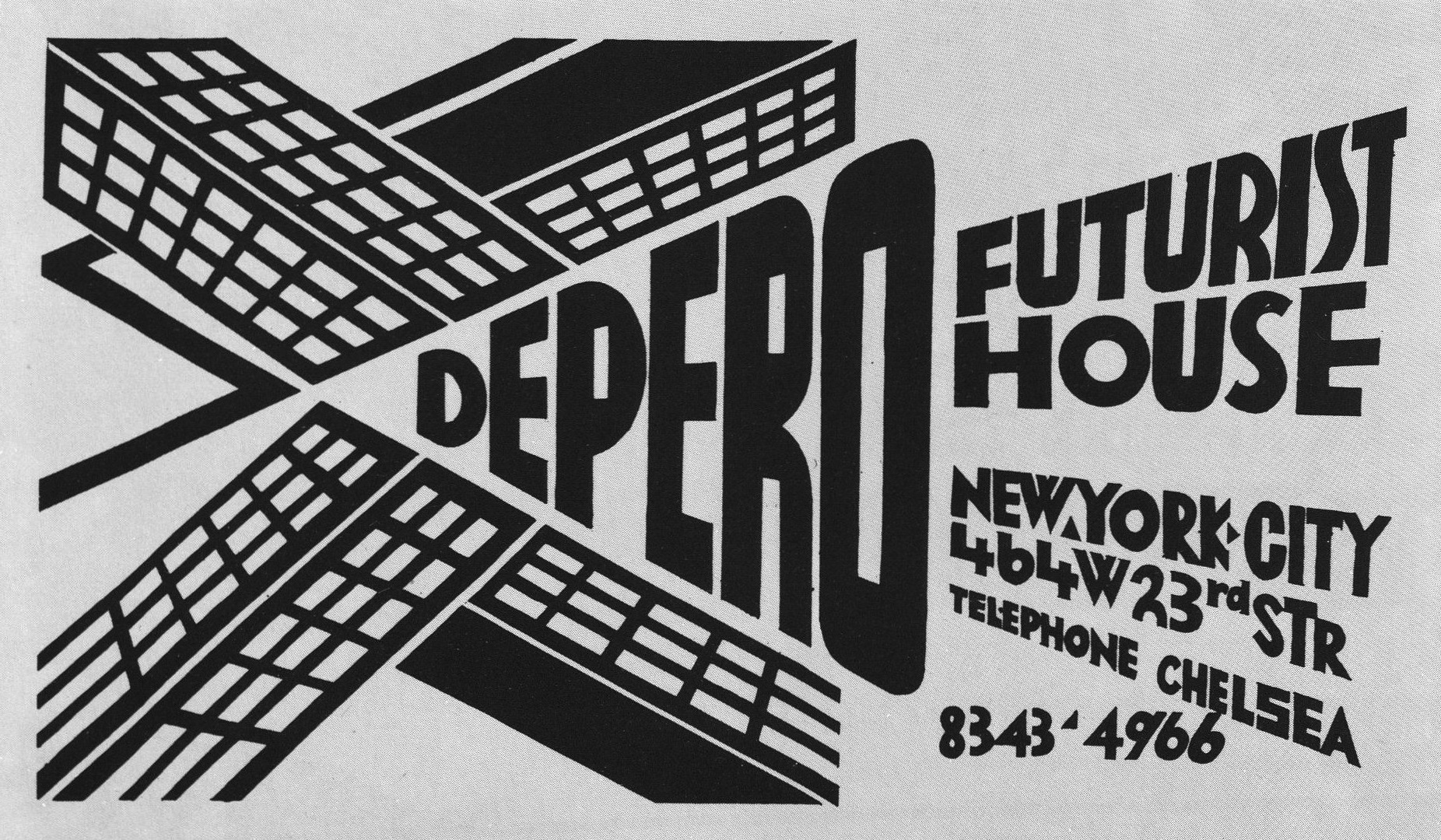

Through his childhood friend, Ciro Lucchi, the artist had arranged a two-year contract with the New Transit Company to open his Futurist House in a hotel on 23rd street in Chelsea.16 The New Transit partners agreed to give him the space in exchange for a small monthly rent of $150 and a 20% commission on sales.17 The Futurist House was to hold a permanent exhibition of Depero’s work and function – similarly to his former studio, the Casa d’Arte of Rovereto – as a workshop for the production of all sorts of projects that aimed to merge the boundaries between fine and applied arts. His American business card listed: “Paintings, plastics, wall panels, pillows, interiors, posters, publicity, [and] stage settings.”18 Depero’s ambition did not stop there; as he wrote to Marinetti, his American dream was to open a Futurist school and then found a Futurist village on the outskirts of New York.19

However, as soon as his feet touched American soil, the artist realized that realizing his goals would be much more difficult than anticipated. For the twenty boxes of art he brought from Italy, he was made to pay high customs fees for the twenty boxes, which he had to borrow money to cover.20 He then had to hire contractors to turn the decrepit Transit Hotel into a usable space; and, far from “smashing the Alps of the Atlantic,” his exhibitions at the Guarino Gallery (with a catalogue text by Christian Brinton) failed to sell a significant amount of his work.21 Disappointed by the artist’s meager earnings, Lucchi and the New Transit partners terminated their two-year contract in April 1929, just five months after the signing, and asked for a high rent which Depero could not afford.22

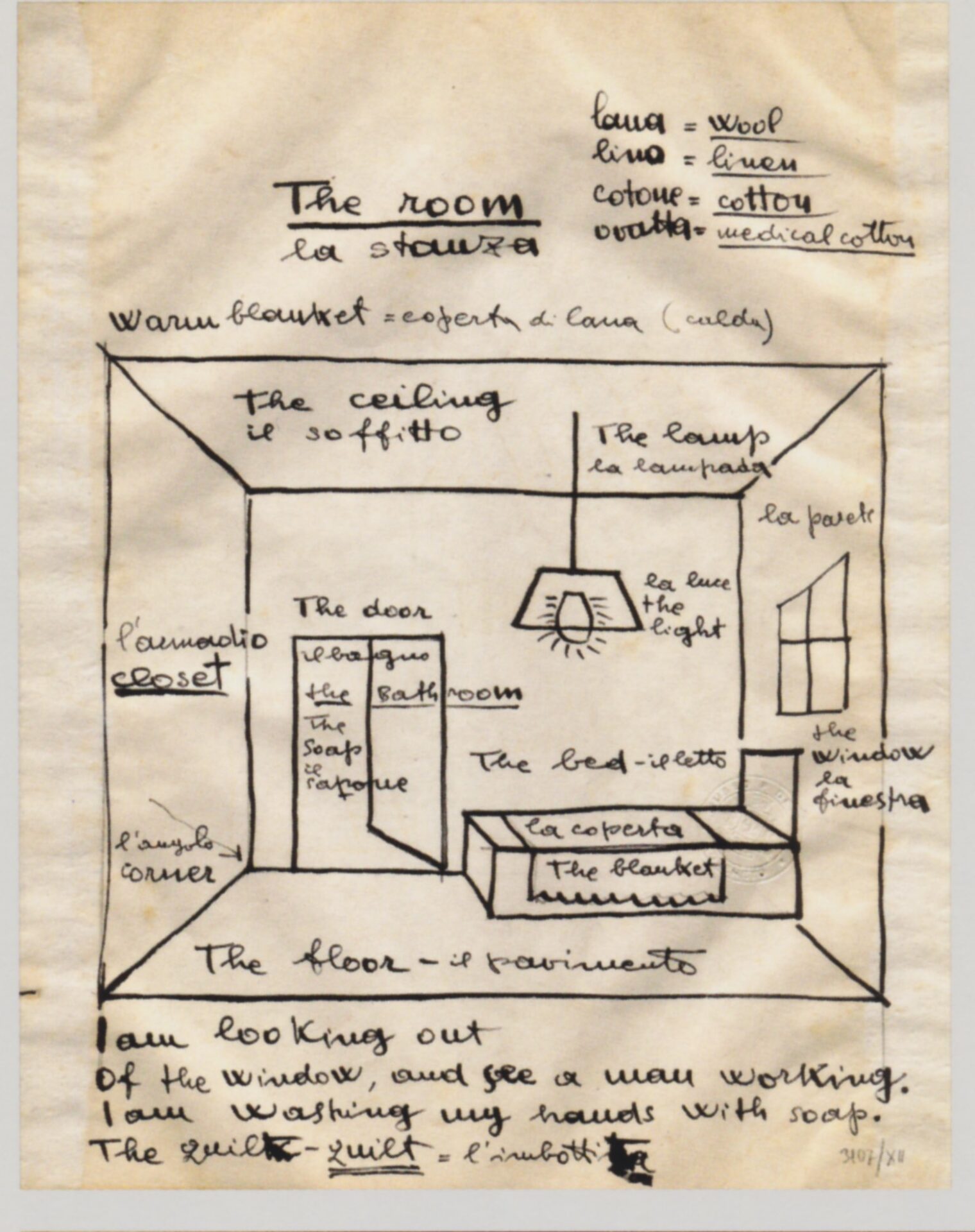

As it happened, the timing of Depero’s journey was extremely unfortunate: with the financial crisis on Wall Street (October 1929) at a climax, it was not the best moment to start a career in New York. Furthermore, Depero did not speak any English (figure 3). He had counted on the large Italian community in New York and on the Italian government’s officials, expecting some support for his activity, which he called “the truest and most ingenuous propaganda for italianità.”23 At the Guarino opening, he gave a speech entitled “Fascism and Futurism Are Brothers,” in which he compared the two movements’ roles in “awakening the Italian genius.” In doing so, he was probably hoping to ingratiate himself with the Italian diplomats and Fascist sympathizers in the audience.24 However, as he complained to Marinetti, his art did not match the local community’s idea of italianità: based on Italy’s grand past, this conception was best expressed by the neo-Renaissance palazzo of the Casa Italiana, which opened in 1927, and not by Depero’s “futurist craziness.”25

In relation to the activities of the Italian government, Depero’s move to New York was also too early. The Fascist regime only started to systematically promote contemporary Italian art in the United States in 1935, during the Ethiopian Campaign, and continued to do so until 1940 – when Italy entered World War II – as part of their efforts to project a positive image of their nation and promote the idea that Fascism had turned Italy into a modern country.26 When Depero arrived in America, Mussolini was popular in the United States and not interested in using contemporary art as a means of propaganda.27 Depero’s applications for financial and institutional support were thus mostly unsuccessful.28 His multiple attempts to generate the sympathy and backing of Italian diplomats in America reached a peak of humiliation when the Italian ambassador in Washington returned one of his originalissimi cuscini (a Depero-designed pillowcase) that the artist had sent as a gift.29

Without institutional support, Depero was forced to turn to other means of making a living. After the Wall Street crash, he and Rosetta offered free Italian food to attract potential clients to his studio. Rosetta cooked homemade ravioli and Fortunato fermented grapes in his bedroom to produce wine – an illegal but lucrative activity during Prohibition.30 Despite his culinary strategies, he received an overwhelming number of refusals. He failed to sell the paintings he brought from Italy, and, out of the many project proposals he sent around, he only obtained some minor commissions. Vogue magazine rejected his sketches, calling them “too heavy.”31 He was luckier with Vanity Fair. But of Depero’s many submissions, the magazine only published two covers, one of which was printed in March 1931, after he had returned to Italy (figure 4).32 His long-time acquaintance, the dancer and choreographer Léonide Massine, secured him a job at the Roxy Theatre. Depero greatly admired that grand temple of cinema and spectacle on Broadway, and depicted it many times in his drawings and free-word compositions, but his role at the Roxy, in reality, consisted only of small, short-term commissions.33 His ambitious proposal of a show focusing on New York – titled The New Babel, characterized by a mobile stage setting – was turned down (figure 5).

Half an hour of tram and subway, half an hour in a wreck of a tramcar through dirty quarters of ghetto. I stumble and curse, smelling a horrible stink. I walk through the thick rain, closing my drawings and my thoughts within a defying scroll which I keep under my arm…. The metal bridges which I cross are gigantic.… I come down from the bridges and get on another tramcar.… I get off. I walk backwards and forwards. I ask, ask again and, at last, an iron door bears the number I am seeking.34

The result of all this trouble was a straight-out rejection.

Return to Italy

When Depero returned to Italy, he produced various works in different media that portrayed his experiences in New York City. The discrepancy between the lack of success he met in the city and his insistence on its significance for his artistic career can be explained, as Günter Berghaus has convincingly proposed, as the result of a form of masochism, a provincialism complex, and a damaged self-image.35 An alternative explanation (not mutually exclusive with the previous one) is that, by insisting on his New York experience, Depero was attempting to document and advertise the fact that he uniquely went to America while other artists still looked to Paris. In doing so, he claimed a leading role in the debate on Americanism, which grew in importance and intensity in Italy during the 1930s. As an increasing number of Italian intellectuals and artists, as well as the government, were directing their attention toward the United States, Depero attempted to carve out a place for himself in this overarching trend.

Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita (1940) was primarily a collection of previously published material. The chapters on New York, in particular, encompassed projects that spanned many years, during which Depero gave lectures, wrote radio programs, and composed articles and tavole parolibere (words-in-freedom compositions), all of which largely focused on the foreign city. His articles on New York appeared in widely distributed newspapers and magazines such as La Sera, Il Secolo XX, and L’Illustrazione italiana (figure 6). Large sections on the city are also featured in Numero unico futurista Campari (a special Futurist Issue Campari in 1931), Futurismo 1932, anno X̊, S.E. Marinetti nel Trentino (Futurism in 1932, 10th Year after the Fascist Revolution, Published on the Occasion of His Excellency F.T. Marinetti’s Visit to Trentino), and in Liriche radiofoniche (Radio Poems, 1934).36 Depero intended to bring together many of these texts in New York. Film vissuto (New York: A Lived Film), a book he carefully designed in the years 1930–1933 that was advertised extensively and partially published in various magazines and newspapers.37 Conceived as the primo libro parolibero sonoro (the first word-in-freedom book with an audio component), Film Vissuto was a complicated and expensive project.38 The fact that it was never realized could in part explain why Depero felt the need to include so many of his texts on New York in Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita.

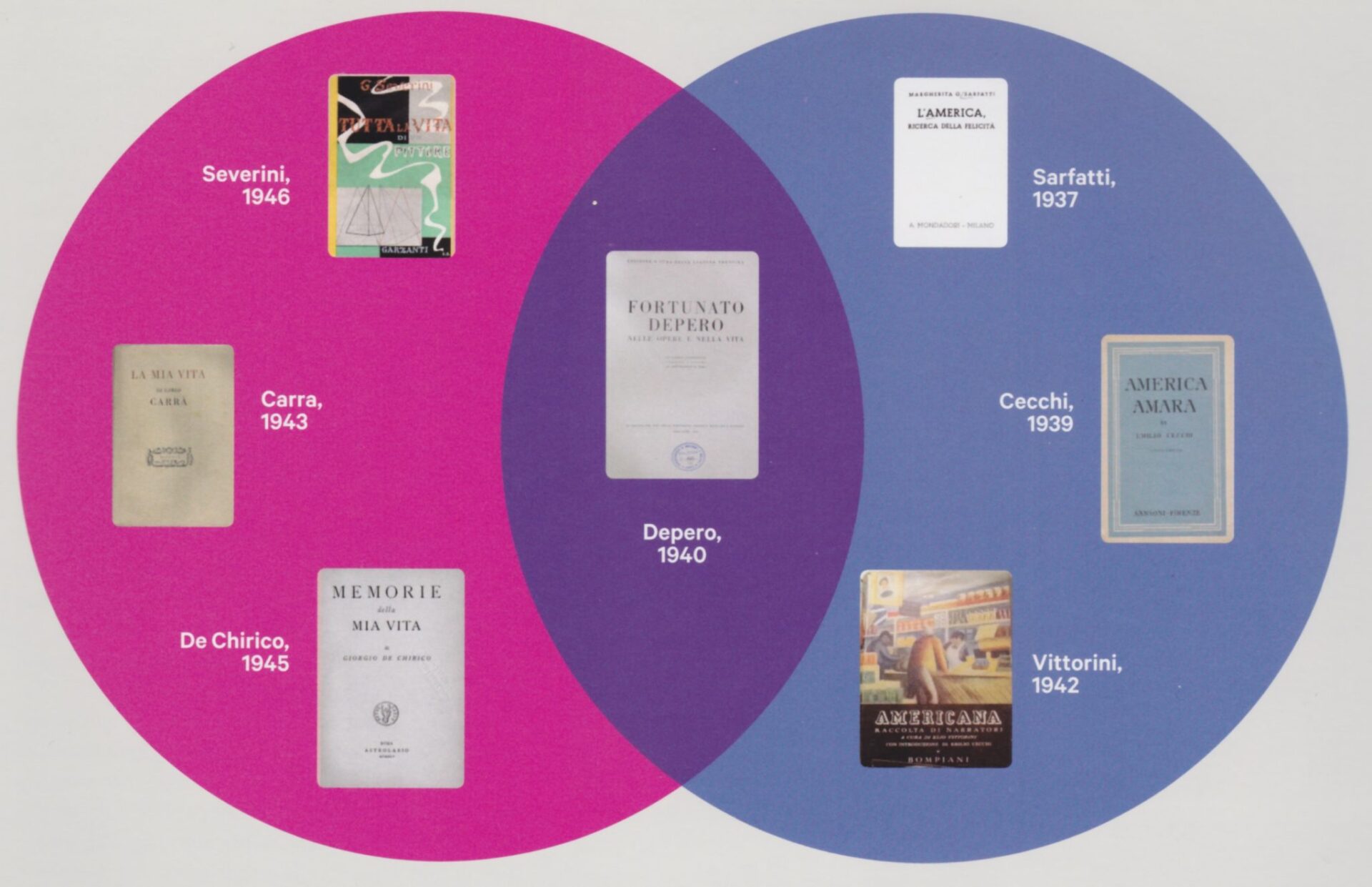

In retrospect, the 1940 volume can be situated between two types of books published in Italy during the 1940s (figure 7): on the one hand, it anticipated a series of memoirs written by older artists – for example, Carlo Carrà’s La mia vita (My Life, 1943), Giorgio De Chirico’s Memorie della mia vita39 (Memoirs of My Life, 1945), and Gino Severini’s Tutta la vita di un pittore (The Full Life Course of a Painter, 1946); on the other hand, it fitted in with a number of publications which, between the late 1930s and early 1940s, focused on the USA as the land of the future. Among the most influential of these were Margherita Sarfatti’s L’America: Ricerca della felicità (America: The Pursuit of Happiness, 1937) and Emilio Cecchi’s America amara (Bitter America, 1939). An important third publication was Elio Vittorini’s anthology of American literature, Americana, which was prepared in the years 1938–1940 and published in 1942, following a notorious case of censorship.

The two groups of books defined modernity in complementary ways. In the first group, the authors claimed for themselves a role as protagonists of the early twentieth-century avant-gardes, which had been historicized during the 1930s. It was therefore a personal and retrospective reflection on a collective, utopian project, which existed in the past. The second group, on the contrary, fulfilled a forward-looking collective desire.

Umberto Eco described the ‘American myth’ as an ideological phenomenon that had provided a generation grown up in Fascist Italy with an image of modernity.40 Cesare Pavese recalled this phenomenon in a similar manner:

American culture became for us something very serious and valuable, it became a sort of great laboratory where with another freedom and with other methods men were pursuing the same job of creating a modern taste, a modern style, a modern world that, perhaps with less immediacy, but with just as much pertinacity of intention, the best of us were also pursuing.… In those years American culture gave us the chance to watch our own drama develop, as on a giant screen.41

Emilio Gentile has argued that during the late 1930s ‘Americanism’ was an important cultural phenomenon for Italian anti-Fascist and Fascist intellectuals alike, “Americanism was, for Fascist culture, one of the main mythical metaphors of modernity, which was perceived ambivalently, as a phenomenon both terrifying and fascinating.”42 The phenomenon transcended social, cultural, geographical, and political divides. Vittorio Mussolini, son of the dictator, enthusiastically reviewed American movies. In 1936, he wrote that Italian Fascist “spirit, mentality, and temperament” were more similar to the American young spirit “than the Russian, German, French, and Spanish ones.”43 Similarly the anti-Fascist activist and partisan Giaime Pintor celebrated “American young blood and candid desires” as opposed to German culture.44 In 1930s Italy, one’s position in relation to American culture, whether in favor of or against it, was an important defining characteristic of an intellectual. It did not correspond to the degree of his or her faithfulness to Fascism but was rather identical to one’s position in relation to modernity.

New York in Depero’s Œuvre

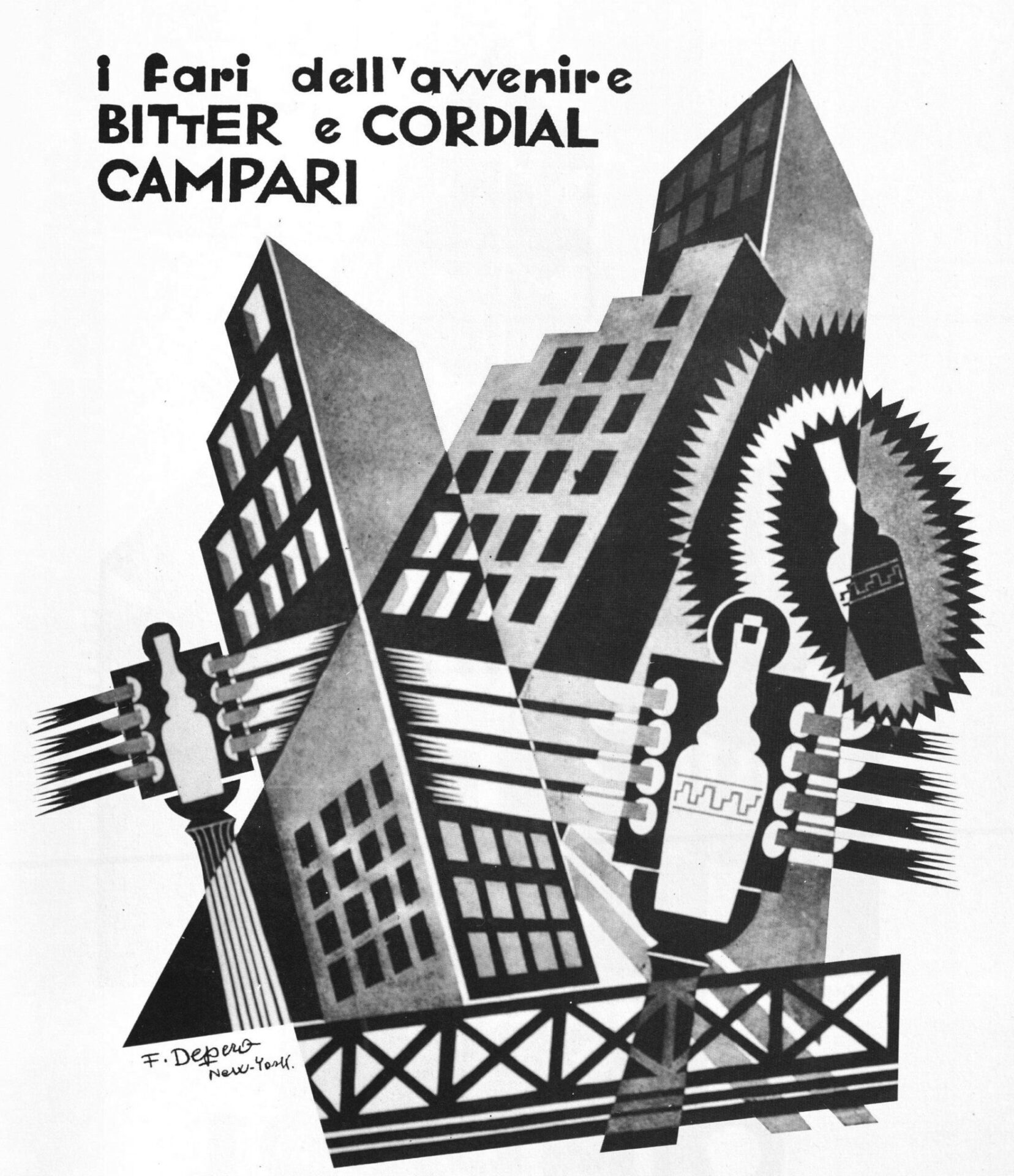

Depero’s books, articles, graphic designs, and paintings following his return from the USA formed part of this conversation on Americanism. As he was one of the earliest and most vocal participants in this debate,45 he also helped to set the tone of the Italian Americanism of the 1930s and 1940s. As was the case for most artists and writers who came after him, his descriptions of New York City were rather ambivalent. On the one hand, he celebrated the grandiosity and dynamism of the modern metropolis – as in his advertisement for Campari (figure 8), where the bottles are turned into streetlights and are called i fari dell’avvenire (the beacons of the future).

Although this image was made for a publicity campaign in Italy, the presence of skyscrapers and the signature “Depero New York”, situated the scene in an American metropolis. In other words, New York was made to represent the positive image of Italy’s avvenire (future). On the other hand, Depero depicted and described the city as a gloomy, oppressive, and alienating environment (figure 9).

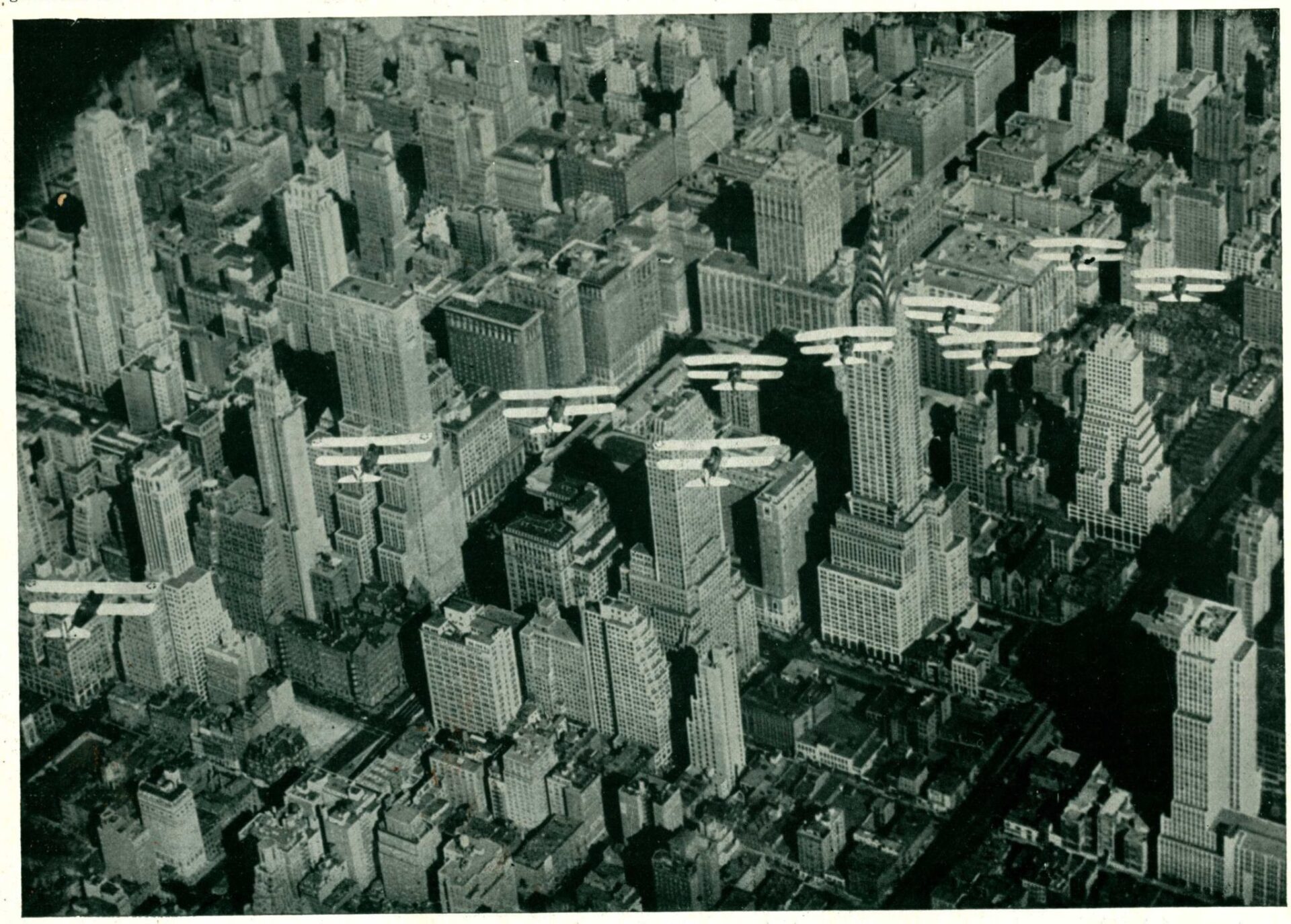

New York in the abstract was seen as the realization of Futurism’s Utopian project of the Total Work of Art. Depero’s description of the city closely followed the words used in the manifesto he authored with Giacomo Balla, Ricostruzione futurista del universo (The Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe; 1915): “dynamic,” “noise-making,” “luminous,” “exploding.” The Futurist idea of the city of the future, as envisioned especially by Umberto Boccioni and by Antonio Sant’Elia, was also heavily influenced by images of New York that had been published in Italian magazines of the 1910s.46

Depero’s first-hand experience of the city proved hard to reconcile with his ideals. The manifesto he co-authored with Balla wanted to re-fashion the universe by “cheering it up… according to the whims of our inspiration.”47 However, thirteen years later, Depero found the modern urban environment, as he wrote to the Futurist artist Gerardo Dottori, “a devil-made metropolis, inhabited by a devil-possessed humanity.”48 He experienced the city as oppressive and alienating, especially in moments of financial hardship. He was yearning for repose in the countryside, as everything went too fast in New York,

Talking in a hurry, saying goodbye in a hurry, visiting in a hurry, doing business in a hurry, getting dressed in a hurry, taking a bath in a hurry. A letter, three letters, a hundred letters, all in a hurry. Conversations always interrupted and all hasty. Phone calls non-stop. Average of daily phone calls in N.Y. twenty-two million. Getting out of the house in a hurry. Take an elevated train in a hurry. Descend into the ‘subway’ in a hurry. Navigate the crowded streets in a hurry, eat in a hurry. Finally a Sunday picnic… maybe relaxed!49

He also wrote, “I do my best to extract myself from the crowd and to go home. I cannot stand it any more. The shops are persecuting me, the skyscrapers are weighing down on me, the illuminated texts are blinding me.”50 Although similar statements would sound normal to any New Yorker, when it is pronounced by a Futurist it becomes a declaration of defeat. For Depero, this reality was all the harder to accept precisely because he identified New York as the manifestation his Utopian ideals.51

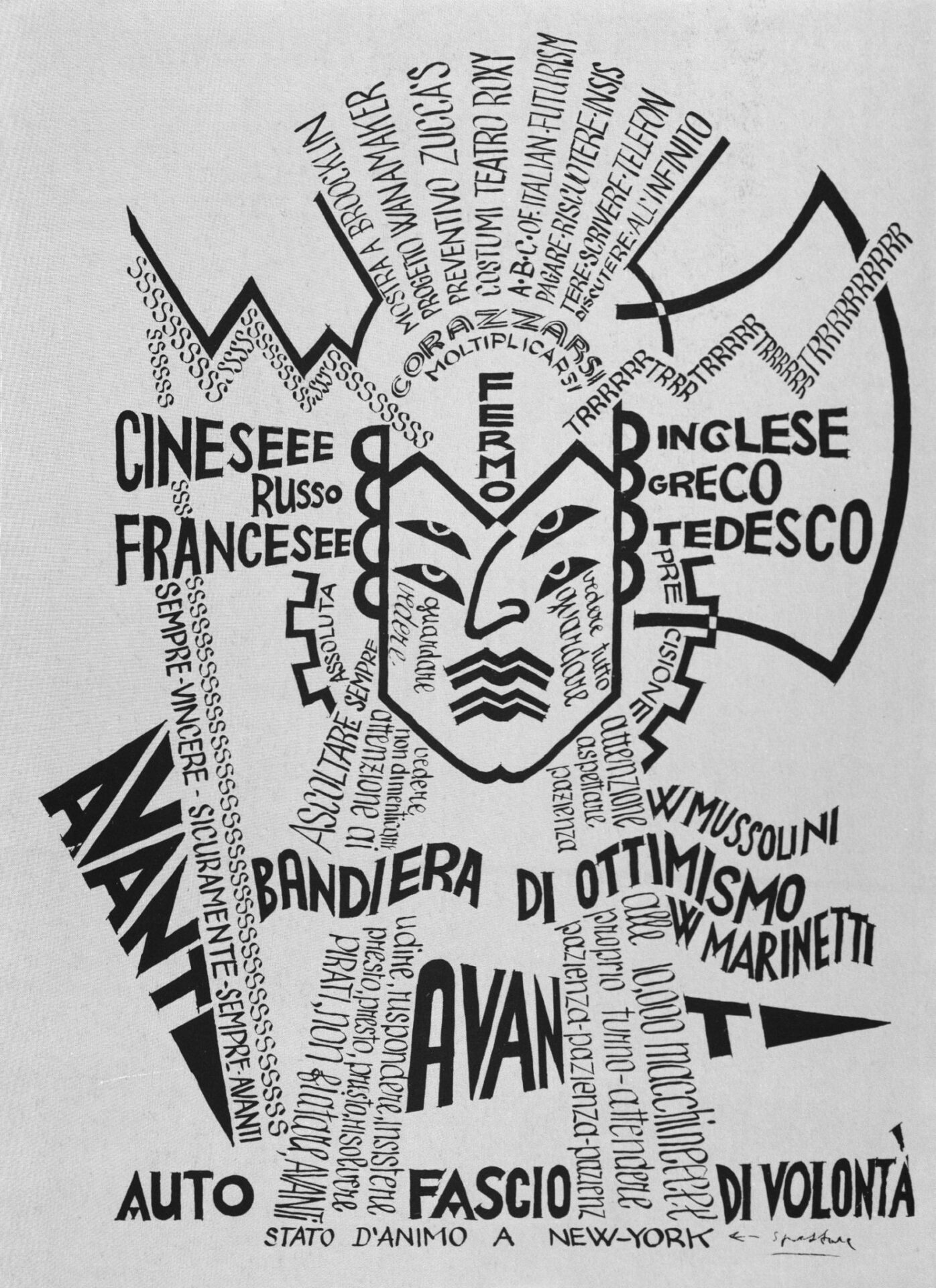

Depero developed a character he described as il mulo metropolitano (the metropolitan mule).52 This human being was a member of the crowd, oppressed by the gigantic machinery of the New Babel. Unlike other Futurists,53 Depero was initially not interested in depicting the crowd. Upon traveling to New York, however, he dedicated many images and reflections to the subject. Even so, Depero’s crowd was not that evoked in Balla’s interventionist paintings, which was unified by its patriotic voice and will; on the contrary; it was rather a crowd fragmented and disoriented by the heavy geometric structure of the city. Giving rise to a sense of instability and chaos, the city’s excessive oblique towers appear as if they are about to implode or crash on top of their inhabitants, as well as those who overcrowd the world of laborers on the ground below. The space of the modern city – the anonymity of its repetitive grid structure, its deplorable working conditions, and its general air of hyper-stimulation – has turned the metropolitan inhabitant into an externally controlled robot. In the 1930 words-in-freedom composition Stato d’animo a New York (State of Mind in New York), Depero expresses how he is overwhelmed by the many languages and stimuli of the city. He therefore turns to his Italian bases of support and certainty, Marinetti and Mussolini, to regain his optimism and move forward (figure 10).

Depero’s negative interpretation of the urbanity is comparable to that of George Grosz – as set forth in his post-war Berlin paintings – and that of Fritz Lang – who used the name “New Tower of Babel” for the corporate headquarters in his famous movie Metropolis (1927). Like Grozs and Lang, Depero reacted to the city with both revulsion and fascination; however, he did not share their anti-capitalist ideology. Depero, in fact, celebrated the consumerism of the Americans. “Every year the Americans remodel their homes – they destroy with remarkable easiness,” he wrote. “They are a fickle, capricious people – and these are great qualities to progress and to keep the market afloat.”54 In his 1931 manifesto Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria (Futurism and Advertising Art) – which was conceived in New York and published in Italy55 – Depero celebrated contemporary industrialists by comparing them to ancient patrons of the arts, and he called advertising the truest and most direct heir of the grand art historical tradition.

Ads and arts in the metropolis

During his stint in New York, Depero realized that the medium of painting was no longer suited for an urban context. He instead embraced advertising, mass media, and popular entertainment as the necessary avenues to survive in the metropolis. Even before going to New York, Depero had worked in various media, all the while dismantling the boundaries between them. Nonetheless, he had still considered painting to be the most prestigious of all arts. In 1927, as he was getting ready to depart, he wrote, “I’m taking with me not only my applied art but also my most important pieces, namely my paintings.”56 In his view, these colorful works were “bombs, concentrated polychromatic explosions”; he claimed, “It will be my pleasure to hurl them against the grim parallelepipeds of this Babel.”57 Accordingly, the first logo of his Futurist House presented a painter’s palette or, alternatively, a target on the façade of three anonymous parallelepipeds (figure 11).58 In theory, the canvases he had brought over from Italy, or, rather, the ‘bomb-paintings,’ were Depero’s weapons to be thrown against the skyscrapers. In practice, however, they proved rather ineffective: nobody took note of them or bought them.

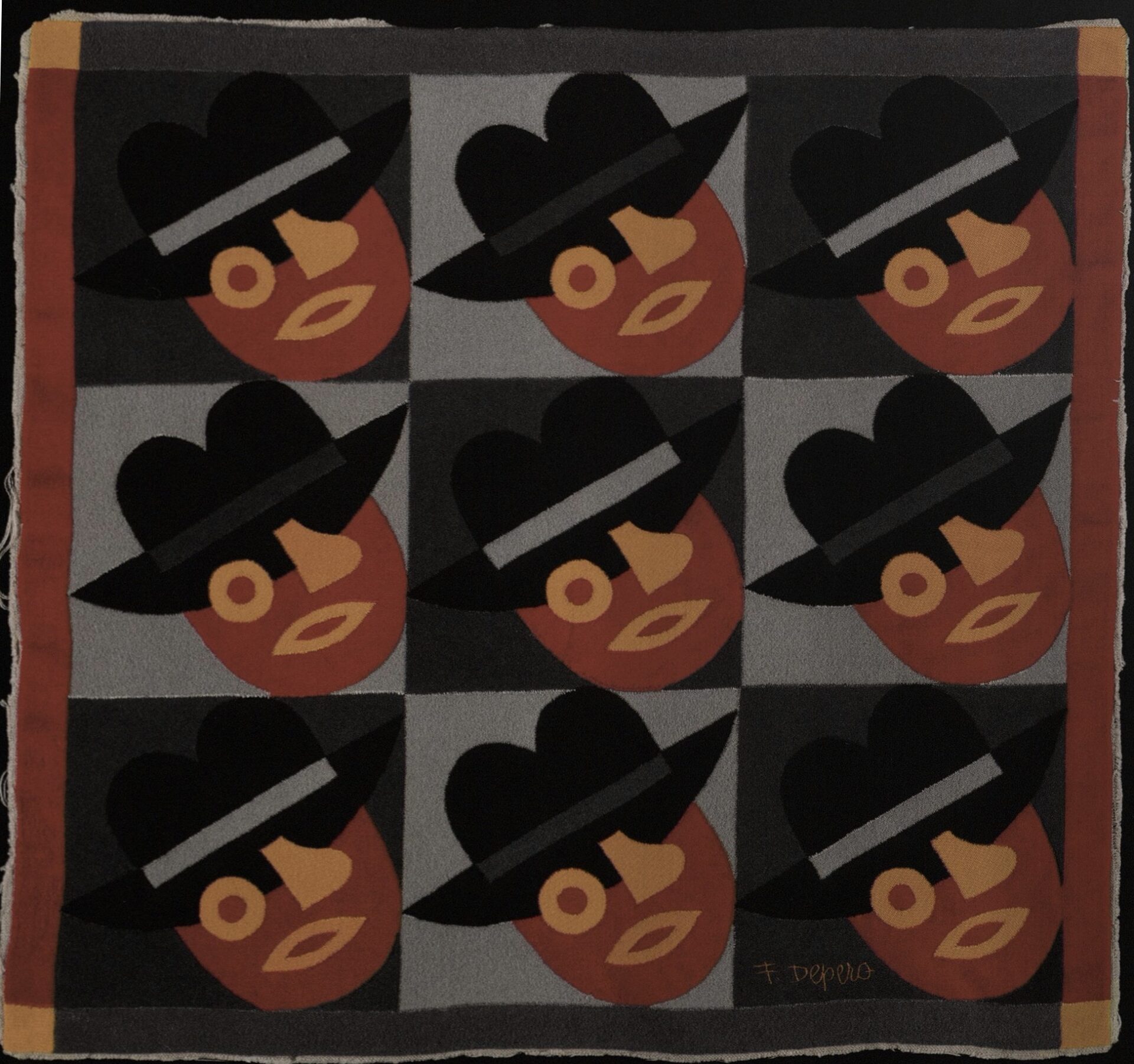

In New York, Depero did not paint. Rather, he celebrated the city’s visual culture through other media. For example, in the 1929–1930 Nove teste con cappello (Nine Heads with Hat), he made use of the grid structure to evoke repetitive quality of life in a metropolis (figure 12).

The pattern contains nine simplified portraits of Al Capone – a quintessential mass-media icon of the time (figure 13) – whose round faces, full lips, bulbous nose (which contrasts starkly from Depero’s typically triangular noses), and fedora hats render them instantly recognizable. The work does not manifest on a canvas (in the style of Mondrian), but on a pillowcase, a practical everyday object. Significantly, Depero had been making pillows for more than a decade before arriving in New York, but in the United States, he decided to abandon the handmade method he had employed in previous years and instead planned a mechanical production line.59 Embracing the popular applied arts and the visual language of advertising, he found an adequate way of reflecting the modern metropolis.

When Depero went to Paris in 1925, he admired the capital’s modern urbanism. He also visited museums and the studio of Constantin Brancusi.60 However, in New York he did not visit other artists’ studios, nor did he seem to notice that the Museum of Modern Art had opened while he was there.61 At least, he did not write about these occurrences. We know from his private notes that he encountered Avant-garde works and met important people from the arts world in New York. However, back home he rarely made any mention of these aspects of his sojourn. For example, he named Katherine Dreier only once: in his autobiography, she is listed as one of the many supporters of his show at the Guarino Gallery. Yet, there is no indication that Dreier publicly endorsed this show, or that she purchased one of Depero’s collages. Furthermore, the artist does not make any reference to her organization, the Société Anonyme. There is also no mention of the fact that Marcel Duchamp dedicated an article to him and published two images from the ‘Bolted Book’ in the Société’s magazine, Quarterly Brochure.62

Founded in 1920, Dreier’s Société Anonyme played a prominent role in the diffusion of modern art in the United States before World War II. However, Depero was apparently more interested in Sparks, a magazine published by the Macy’s department store for its employees.63 Even more important for him was everyday entertainment. He celebrated the Roxy Theatre and the Paramount building with great enthusiasm, and his publications often focused on popular films, such as the series Our Gang (also known as Little Rascals), which primarily features child actors:

They set the house on fire, attached a donkey to a cart full of ladders, ropes and watering cans. Dressed up like firemen, they improvise rescue operations… It’s a spectacle of children genius that I greatly enjoyed.64

Depero also found inspiration in Frederick Kiesler’s De Stijl-inspired architecture for the Film Arts Guild’s Cinema on 52–54 West Eighth Street. Depero devoted a chapter of his 1940 book to this building. However, he did so not because of its modernist architecture, but because, to him, it stood as a symbol of consumer culture. As he expressed in his texts and projects concerned with architettura pubblicitaria (commercial architecture), Depero was fascinated by architectural forms that were able to represent and advertise (but not necessarily follow) their function.65

A building whose external architecture and internal environments were inspired, both in style and in mechanical function, from a movie camera.… the façade is made out of blocks, curves and gears. The waiting room features metal walls and ladies wearing red and black cloves. The interior of the [projection] hall is a kind of trapezoidal funnel. At the end, the rounded curtain opens and closes itself like the aperture of a ‘Zeiss.’66

Although Depero seems not to have cared for artists’ studios or modern art galleries, he did take aesthetic pleasure from other places. “They told me that in America there is no art… this is not true,” he wrote. “The skyscrapers offer audacious perspectives, only interrupted by advertising, luminous machines… exuberant and enormous publicities. Lights that drop and explode and spin dramatically, directing the stream of the crowd in a rhythmic flux and re-flux of a thousand colors.”67 For Depero, the city itself was an immersive and multi-sensory work of art and advertisement was the most effective way for the artist to capture its aesthetic allure.

Before moving to New York, Depero had believed advertising to work like a megaphone. Once he had arrived in the United States, he realized that the city itself was the most powerful megaphone. He expressed this idea in a new logo (figure 14), wherein the original painter’s palette has been substituted with the name ‘Depero.’ Thanks to this revision, the skyscrapers no longer stand as targets against which the artist throws his ‘painting-bombs;’ they instead collectively function as a megaphone shouting his name. Ironically, similar buildings would later serve as advertising boards for Depero’s Campari campaigns: the metropolitan structures that neutralized the effect of his paintings were subsequently turned into the artist’s primary medium of publicity.

In this case, Depero’s fervid imagination once again exceeded his actual achievements in New York. In reality, he produced none of the gigantic billboards, monumental balloons, or explosive fireworks that he described in his writings. However, back in Italy he expressed these ideas – about the role of the modern metropolis as a megaphone for the artist’s voice and of advertising as a new form of art – by means of his manifesto, Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria, and through his activity for the Campari beverage company.68 In the works Depero made for Italian audiences, New York skyscrapers manifested as a topos and functioned simultaneously as actual places and metaphors. As both a real city and a symbol of modernity, New York not only served as a marketing tool to promote Campari, but also as a means of self-promotion for the artist. Through a deliberate mixture of fact and fiction, Depero exploited the manipulating power of mass media, just as Marinetti had done since the publication of his Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism in 1909.69 Marinetti initiated calling the bluff on Depero’s alleged “triumphs in America”70 in a 1929 article and, again, at the Venice Biennale of 1932. Yet, Depero continued reiterating his fictional account for two decades in articles, lectures, radio programs, books, and memoirs.

The second visit to New York in 1947–1949

Depero’s choice to return to New York in 1947 and, later, to translate his memoirs into English are surprising at best. The book was filled with self-congratulatory stories about his success in New York. Bringing the text to American audiences was thus a short-circuit of fictional invention with real experience. This blatant discordance between fantasy and reality raises the following question: did Depero end up believing his own myths?

In the newly added introduction to So I Think, So I Paint, Depero expressed the will to “heartily dedicate this work of mine to American youth that, fortunately, has not before its eyes and within its mind the warning and encumbrant [sic] phantom of tradition and convention.” He also wrote, “You, you Americans who have the luck of ignoring these spiritual barriers [tradition and convention], you can throw your new energies towards the most free aspirations of life, for you are ripe with independence and with lived and conquered experience.”71 Like many Italians in the aftermath of World War II, Depero saw in America a nation that lived in the present rather than languishing in its past burdens. For post-war Americanists, the country therefore represented a land of opportunities and a new beginning.72

Given American’s contribution to the liberation of Italy from Fascism and the fall of Mussolini, the pro-American sentiments of the 1930s were revisited and modified by the Cold-War rhetoric of a rebirth of Italy under the aegis of a Pax Americana. It was not by chance that 1947 was the year when Pavese wrote a first essay on 1930s Americanism.73 The same year, Carlo Levi published an article in Life magazine, entitled “Italy’s Myth of America,” in which he described how the nineteenth-century “vision of America as the promised land” had been revived and reshaped by the United States through their contribution to the “reconstruction” of Italy. That vision, Levi declared, had never been “stronger or more fanciful than today.”74 He illustrated his article with photographs of US soldiers distributing food to Italian peasants, a ubiquitous image in post-war Italy, which the starving Depero knew well. Depero also had direct knowledge of the profitable business conducted by his close friends and patrons in New York and Milan, John Salterini and Gianni Mattioli.75 More than anyone, these two industrialists – to whom Depero dedicated So I Think, So I Paint – offered him financial support and encouraged him to undertake his second trip to New York.

In 1947, Depero was economically destitute and politically compromised. He had embraced the most aggressive Fascist propaganda until the end. As late as 1943, he published A passo romano (Roman Step), a book that featured Fascist and Nazi symbols combined with racist and imperialist slogans.76 This made his need to leave Italy all the more urgent and the prospect of a new beginning in America all the more attractive.77

But, again, the artist’s inexhaustible optimism collided with reality. If Depero’s first trip to New York was a failure, the second resulted in a painful and systematic dismantlement of his Futurist myth of New York. He spent the winter 1947–1948 hosting Salterini, a metal furniture producer, whose slogan ‘never rust’ mirrored Depero’s own Futurist slogans, but sadly contrasted the precarious situation in which the old artist then found himself. While housing Salterini, Depero had to leave his lodgings early in the morning – when the employees and clients of Salterini arrived – and could not come back until it was late at night, when the machines had been switched off. Recurring themes in his letters from this period were coldness, hunger, and loneliness. He lost most of his teeth and fell into a state of deep depression. His main hope rested on the exportation of Buxus, a sort of synthetic wood he had used for some of his furniture, to the United States. “What is the Buxus?” was title of the only section of So I Think, So I Paint that was entirely new. In this text, Depero explained the great advantages that Buxus offered “to architects, engineers, furnishers and decorators!”78 But the project proved unrealistic. A substitute to wood promoted in the 1930s as part of Mussolini’s autarchy policy, Buxus was a reminder of Italy’s (and Depero’s) Fascist past and imperialistic rhetoric (figure 15).79 Furthermore, the industry in post-war America did not need any wood substitutes.

Being a Futurist also did not help Depero either. Futurism did not enjoy much success in the United States, before or after the Second World War.80 Its reception would not change until 1949, when the Museum of Modern Art rehabilitated the movement through the major exhibition, Twentieth-century Italian Art.81 Depero’s repeated attempts to be included in the show were frustrated by the curators’ choices of artworks.82 Organized by Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and James T. Soby, the exhibition established a canonical reading of the movement, which rested on the ‘heroic’ phase (1909–1915) that occurred before Mussolini and before Depero.83 MoMA also limited its appreciation of Futurism to painting and sculpture, which was not compatible with Depero’s multi-sensory, immersive idea of a ‘Futurist Universe.’

In the spring of 1948, Depero left the Salterini factory, as well as New York. His wife Rosetta joined him and together they moved to New Millford, Connecticut, where they worked as housekeepers in the holiday mansion of William Hillman and Angela Sermolino, a wealthy New York couple. With this change of environment, Depero’s health and mood recovered. “Everything has changed for the best,” he wrote to a friend.84 He resumed painting and enjoyed the quietness of rural life, “Cars are rare, because here we are really in the countryside with huge farms and spotted cows.”85 Painting cows in the silence of the New England countryside turned out to be the absurd, anti-climatic epilogue of Depero’s strange love affair with New York.

Conclusion

Although unrequited, Depero’s delusional affair with New York enjoyed an unlikely posthumous fortune among art historians. After his death in 1960, the artist’s period in the city gained more and more importance, and the myths he had forged ended up interfering with and even dictating the art historical narratives written about him.86 The legend of his ‘American triumphs’ has thus survived on paper through countless books and catalogues.87 My effort to disentangle his myths from documentary evidence does not aim at the distillation of historical truth. Rather, I emphasize the act of myth-making as historically significant to understanding the overlaps and collisions between Depero’s utopian ideas of modernity and his experience as an immigrant in the modern city. The resulting story is non-linear and rather tragic: against the backdrop of the Great Depression, the end of Fascism, and the beginning of the Cold War, Depero’s vision of a Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe found in New York its most exhilarating model as well as its most fatal battlefield.

Bibliography

Barr, Alfred H. Jr. Cubism and Abstract Art. New York: MoMA, 1936.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949.” Oxford Art Journal 35, 2 (June 2012): 147–169.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “‘I Will Smash the Alps of the Atlantic’: Depero and Americanism.” In Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, edited by Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, 329–337. Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Bedarida, Raffaele. “’Bombs against the Skyscapers’: Depero’s Strange Love Affair with New York, 1928–1949.” In International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, vol. 6, edited by Günter Berghaus, 43–70. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2016.

Belli, Gabriella, ed. Depero futurista: Rome – Paris – New York, 1915–1932 and More. Milan: Skira, 1999. Exhibition Catalogue.

Belli, Gabriella and Beatrice Avanzi, eds. Depero pubblicitario: Dall’auto-réclame all’architettura pubblicitaria. Milan: Skira, 2007. Exhibition Catalogue.

Belloni, Fabio. “The Critical Fortune and Artistic Recognition of the Work of Depero.” In Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, edited by Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, 347–353. Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Benzi, Fabio. Art Déco. London: Taylor & Francis, 2004.

Berghaus, Günter. Futurism and Politics: Between Anarchist Rebellion and Fascist Reaction, 1909–1944. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1996.

Berghaus, Günter. Italian Futurist Theatre. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Braun, Emily. “Vulgarians at the Gate.” In Boccioni’s Materia, edited by Laura Mattioli Rossi, 1–21. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2004.

Brinton, Christian, ed. Exhibition of Modern Italian Art. New York: Italy America Society, 1926.

Carrà, Carlo. La mia vita. Rome: Longanesi, 1943.

Caws, Mary Ann, ed. City Images: Perspectives from Literature, Philosophy, and Film. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1991.

Cecchi, Emilio. America amara. Florence: Sansoni, 1939.

Chiesa, Laura. “Transnational Multimedia: Fortunato Depero’s Impressions of New York City.” California Italian Studies 1, 2 (2010): 1–33.

Coen, Ester. “We Will Sing of Great Crowds = Canteremo le grandi folle.” In Faces in the Crowd: Picturing Modern Life from Manet to Today, edited by Iwona Blazwick, 34–39. Milan: Skira, 2004.

Cortesini, Sergio. ‘One day we must meet’: La politica artistica italiana e l’uso dell’arte contemporanea come propaganda dell’Italia fascista negli Stati Uniti tra 1935 e 1940. PhD Dissertation. Rome: Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza, 2003.

Crispolti, Enrico, ed. Nuovi archivi del futurismo. Rome: De Luca, 2010.

Dall’Osso, Claudia. Voglia d’America: il mito americano in Italia tra Otto e Novecento. Rome: Donzelli, 2007.

De Chirico, Giorgio. Memorie della mia vita. Rome: Astrolabio, 1945.

Depero, Fortunato. “Corteo pubblicitario ‘Macy’.” La Sera (September 23, 1931).

Depero, Fortunato. Depero futurista. Milan: Dinamo Azari, 1927.

Depero, Fortunato. “Il futurismo negli Stati Uniti: L’opera di Depero esaltata dalla stampa americana. L’attività dell’artista a New York.” L’Impero (August 8, 1929).

Depero, Fortunato. Numero unico futurista Campari. Milan: Campari, 1931.

Depero, Fortunato. “A zig zag per la Va Avenue.” La Sera (August 24, 1931).

Depero, Fortunato. “Fuoocoo – Con Massine all’Auditorium – Un delinquente a sei anni.” La Sera (September 2, 1931).

Depero, Fortunato. “La questione ‘vino’.” La Sera (September 30, 1931).

Depero, Fortunato. “Traversata Atlantica.” La Sera (October 21, 1931).

Depero, Fortunato. “Fuori New York – Torto, Polento, Ticcio, Pasto – Una giornalista Italo-americana.” La Sera (November 23, 1931).

Depero, Fortunato. “Ristorante cinese in Broadway – Un ingegnere giapponese.” La Sera (December 2, 1931).

Depero, Fortunato. Futurismo 1932. Rovereto: Mercurio, 1932.

Depero, Fortunato. “Itinerario giornaliero di un professionista newyorkese – Una segretaria ideale.” La Sera (January 22, 1932).

Depero, Fortunato. “Un portiere – Primo quadro: la ballerina di cenci – ‘The Black King’ – Coniugi mulatti in calesse.” La Sera (June 7, 1932).

Depero, Fortunato. “Manifesto: Arte pubblicitaria futurista.” Futurismo 1, 2 (June 1932): 4.

Depero, Fortunato. “New York come l’ho vista io.” Il Secolo XX 32, 7 (February 18, 1933).

Depero, Fortunato. Liriche radiofoniche. Milan: G. Morreale, 1934.

Depero, Fortunato. “Vertigini di Nuova York.” L’Illustrazione Italiana 61, 25 (June 23, 1935): 1051–1052.

Depero, Fortunato. Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita. Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1940.

Depero, Fortunato. A passo romano: lirismo fascista e guerriero programmatico e costruttivo. Trento: Edizioni Credere Obbedire Combattere, 1943.

Depero, Fortunato. So I Think, So I Paint: Ideologies of an Italian Self-made Painter. Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1947.

Duranti, Massimo. Dottori: Futurist Aeropainter. Perugia: Effe, 1998.

Eco, Umberto, Gian Paolo Ceserani, and Beniamino Placido, eds. La riscoperta dell’America. Bari: Laterza, 1984.

Fagiolo Dell’Arco, Maurizio, ed. Depero. Milan: Electa, 1989. Exhibition catalogue.

Gentile, Emilio. “Impending Modernity: Fascism and the Ambivalent Image of the United States.” Journal of Contemporary History 28, 1 (January 1993): 7–29.

Ginex, Giovanna. “Not just Campari! Depero and advertising.” In Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, edited by Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, 308–317. Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Greene, Vivien, ed. Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

Levi, Carlo. “Italy’s Myth of America.” Life 23, 1 (July 7, 1947): 84–86, 89–95.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. “Mostra dell’Aeropittura e della Pittura dei Futuristi Italiani.” In XVIII Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte, 168–175. Venice: Biennale di Venezia, 1932.

Mattioli Rossi, Laura. “The Collection of Gianni Mattioli from 1943 to 1953.” In The Mattioli Collection: Masterpieces of the Italian Avant-garde, edited by Flavio Fergonzi, 13–57. Milan: Skira; London: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

Pavese, Cesare. “Ieri e oggi.” L’Unità (August 3, 1947). English translation: “Yesterday and Today.” In American Literature: Essays and Opinions, 196–199. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.

Poggi, Christine. “Folla/Follia: Futurism and the Crowd.” Critical Inquiry 28, 3 (Spring 2002): 709–748.

Rainey, Lawrence, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman, eds. Futurism: An Anthology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Ruele, Michele, ed. Depero: Lettere inedite dagli USA e arazzi della collezione ITAS. Rovereto: Via della Terra, 2004.

Salaris, Claudia, ed. Fortunato Depero: Un futurista a New York. Montepulciano: Del Grifo, 1990.

Sarfatti, Margherita. L’America: Ricerca della felicità. Milan: A. Mondadori, 1937.

Severini, Gino. Tutta la vita di un pittore. Milan: Garzanti, 1946.

Scudiero, Maurizio and David Leiber, eds. Depero futurista & New York: il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria. Rovereto: Longo, 1986. Exhibition Catalogue.

Société Anonyme. “Exhibitions.” Quarterly Brochure 2 (December 1928–January 1929): 20–27.

“The Past and the Present of a Futurist.” Vanity Fair 36, 1 (March 1931): cover; 31.

Torriglia, Anna Maria. Broken Time Fragmented Space: A Cultural Map for Postwar Italy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Vanity Fair 34, 5 (July 1930): cover.

Vittorini, Elio, ed. Americana. Milan: Bompiani, 1942.

Whyte, Iain Boyd. “Futurist Architecture.” In International Futurism in Arts and Literature, edited by Günter Berghaus, 353–372. New York: de Gruyter, 2000

How to cite

Raffaele Bedarida, “‘Bombs Against the Skyscrapers’: Depero’s Strange Love Affair with New York, 1928–1949,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/bombs-against-the-skyscrapers-deperos-strange-love-affair-with-new-york-1928-1949/, accessed [insert date].

- Research for this essay was conducted as part of my 2013–2014 fellowship at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York. I extend my gratitude to Laura Mattioli, Heather Ewing, and Fabio Belloni, with whom I have shared my experience at CIMA. The essay derives from two shorter texts: a paper for the Study Day on Fortunato Depero (CIMA, February 21, 2014); and the essay “‘I Will Smash the Alps of the Atlantic’: Depero and Americanism” for Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, eds. Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, exh. cat. (Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014), 329–337. I am very much thankful to Emily Braun and to Günter Berghaus for their insightful comments on the manuscript. The present version was previously published in International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, ed. Günter Berghaus, vol. 6 (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2016), 43–70. I thank both editor and publisher for granting me the right to republish it. Archival sources from: MART – Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto (from now MART). Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero; Mattioli Archive (Fortunato Depero correspondence); Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven (Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Papers, Box 10, Folder 214); The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA (Special Collections, Fortunato Depero papers).

- Fortunato Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita (Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1940), 239. The translation is mine.

- Fortunato Depero, So I Think, So I Paint: Ideologies of an Italian Self-made Painter (Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1947), III. The dates given by Depero are in fact incorrect. He arrived in October 1928 and left in October 1930.

- Depero, So I Think, 109.

- These cities appear in other chapters dedicated respectively to: inspirational figures (Incitatori); theory (Ideologie d’artista); painting (Opera pittorica); tapestries (Arazzi Depero); furniture and interior design (Nuovo orizzonte artigiano); and theatre (Teatro plastico).

- See Maurizio Scudiero and David Leiber, eds., Depero futurista & New York: il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria, exh. cat. (Rovereto: Longo, 1986); the anthology of Depero’s writings on New York Claudia Salaris, ed., Fortunato Depero: Un futurista a New York (Montepulciano: Del Grifo, 1990); and Gabriella Belli, ed., Depero futurista: Rome-Paris-New York, 1915–1932 and More, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 1999) which emphasized the latter of the three capitals, starting from the cover image. More recently, see Laura Chiesa, “Transnational Multimedia: Fortunato Depero’s Impressions of New York City,” California Italian Studies 1, 2 (2010): 1–33.

- See Gabriella Belli and Beatrice Avanzi, eds., Depero pubblicitario: Dall’auto-réclame all’architettura pubblicitaria, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2007).

- Günter Berghaus, Italian Futurist Theatre (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 484.

- Depero to Franco Rampa Rossi (Milan 1922), reproduced in Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 243. Again, in 1923, Depero wrote to Rampa Rossi about his projected trip to New York, “Non potró partire per New York prima di maggio – giugno. Troppe cose da assestare.” Depero to Rampa Rossi (September 19, 1923; Mattioli Archive).

- The industrialist and collector Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi was the main sponsor of his trip. See Salaris, Fortunato Depero, 217. Fedele Azari (1895–1930) conducted business in New York and was probably part of Depero’s enthusiasm for the city. In the spring of 1928, when the project materialized, however, Azari warned Depero about the difficulties and the taste gap he would encounter in America. See Beatrice Avanzi, “Fortunato Depero e la pubblicità: un’arte ‘fatalmente moderna,’” in Belli and Avanzi, Depero pubblicitario, 31–32.

- Fortunato Depero, “Il futurismo a New York,” 1929 manuscript, reproduced in Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 218. Quoted here from Depero, So I Think, 108.

- Depero to Marinetti (October 2, 1928; in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Papers, Box 10, Folder 214, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven). The translation is mine.

- Fortunato Depero, Depero futurista (Milan: Dinamo Azari, 1927).

- Exhibition of the Italian Book, March 15–30, 1929, Arnold-Constable & Co., Fifth Avenue, New York.

- Depero to Marinetti (October 2, 1928), in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Papers, Box 10, Folder 214, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven.

- The New Transit Hotel.

- Depero, Depero futurista, 150, nn. 1 and 2.

- Depero’s Futurist House business card (1929), reproduced in Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 127.

- “Credo riuscirò a creare col tempo il mio sognato villaggio futurista.” Depero to Marinetti (October 2, 1928). He talks about the project of a futurist school in another letter: Depero to Marinetti (April 25, 1929; in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Papers, Box 10, Folder 214, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven).

- Salaris, Fortunato Depero, 25: “Casse e bauli di quadri, disegni ed arazzi requisiti e mandati in dogana dove sostano per ben due mesi e sono poi rilasciati dopo cento consulti e con il pagamento del dazio di ben 15.000 lire (diconsi quindici mila lire) che non possedevo.”

- The flyer for the Guarino show listed carefully the titles of seventeen paintings and seventeen tapestries, but only mentioned generic “drawings and posters” and “pillows,” which were obviously less important. Depero’s private note on the exhibition sales, however, listed only five pillows and one drawing. None of the important (and expensive) pieces were sold. See “Attività Depero a New York, Manoscritto, 10 pp.” in Enrico Crispolti, ed., Nuovi archivi del futurismo (Rome: De Luca, 2010), 310.

- Depero had to pay $1,200 for the termination of the agreement. He renounced his large workshop and exhibition space and only kept a bedroom, kitchen, and shared restroom. He was then hosted by his friend John Salterini and later moved to a less expensive apartment on 11th Street.

- “E’ la più vera e più geniale propaganda d’italianità che sto facendo.” Depero to Marinetti (April 25, 1929; in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Papers, Box 10, Folder 214, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven).

- “Fascismo e Futurismo Sono Fratelli,” manuscript of the inaugural speech given by Depero on January 8, 1929 at the opening of his show at the Guarino Gallery, New York, p. 6 (Fortunato Depero papers, Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA). I extend my gratitude to Fabio Belloni for sharing this document.

- Depero to Marinetti (January 13, 1929; in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Papers, Box 10, Folder 214, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven).

- Between 1935 and 1940, the regime sponsored no less than twelve contemporary Italian art exhibits in the United States. Firstly, by financing the initiatives of the Italian art dealers Dario Sabatello (from 1935 to 1937) and Mimi Pecci Blunt (from 1937 to 1938); secondly, by sending official shows of contemporary Italian art at the Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco (1939), at the International Women Painters, Sculptors, Gravers (New York, Riverside Museum, 1939), and at the two editions of the New York World’s Fair of 1939 and 1940. These gave only little space to Futurism. See Sergio Cortesini, “‘One day we must meet.’ La politica artistica italiana e l’uso dell’arte contemporanea come propaganda dell’Italia fascista negli Stati Uniti tra 1935 e 1940” (PhD dissertation. Rome: Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza, 2003).

- The only show organized by the regime in the United States before 1935 was the 1926 Exhibition of Modern Italian Art, curated by Christian Brinton under the patronage of the Italian Government, which opened at the Grand Central Art Galleries in New York. The show, which included four paintings by Depero, is an important precedent to Depero’s American enterprise. Brinton was a major supporter of futurism in the United States and a friend of Depero’s collector and collaborator, Fedele Azari.

- It is unclear from Depero’s description whether a promised grant from the Italian Government was withdrawn or just proved insufficient to support the artist. He described how his American enterprise was made possible by the financial support of the industrialist and philanthropist, Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi, “raggiungo Genova fiducioso in seguito ad una promessa ottenuta a Roma di avere una riduzione sul dispendioso viaggio. Invece delusione completa.” [As a result of a promise obtained in Rome to have a reduction on the expensive trip, I reach Genoa confident. Instead complete disappointment], in Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere, 275–277. In a letter to his friend and collector, Gianni Mattioli he explained more in detail: “3 giorni prima di salpare non avevo denaro bastante dovendo dare anticipo sul ritorno e non ottenendo riduzione alcuna. Avevo la disperazione nell’anima – Rosetta piangeva lagrime come le noci – io pazzo non dormivo. Alla vigilia della partenza al momento di versare il totale un carissimo amico di Genova industriale, comprese il mio stato d’animo e mi regaló 10,000 Lire.” Undated letter postmarked December 7, 1928 (Mattioli Archive).

- Depero had sent the pillow as a present but the ambassador, afraid that a payment was expected, wrote that it the sending of the pillow “was an equivocation.” Letter from Ambasciata d’Italia to de Pero [Fortunato Depero] (December 18, 1928; MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero, Folder “Libro imbullonato e viaggio in America,” Dep.3.1.16.22).

- For Depero’s description of how the idea of hosting Italian dinners arose, see Depero, So I Think, 127–128.

- Condé Nast Publications to Depero (March 27, 1930; MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero, Folder Corrispondenza sciolta, 1930).

- Vanity Fair published Depero designs on the covers of its July 1930 and March 1931 issues. The latter also included a short article, “The Past and the Present of a Futurist” on p. 31, which reproduced a different version of the cover’s motif.

- In a page that, retrospectively, reads like one of Paolo Villaggio’s popular parodies of the submissive employee from the 1970s, Depero recalled a midnight dialogue between him and the artistic director of Roxy Theater, Leon Leonidoff: “‘Good evening, Mr. Leonidoff.’ ‘Good evening, Mr. Depero. I need urgently two sketches of scenes and three sketches of costumes for tomorrow morning at eleven.’ ‘Why, you are crazy! How can I do it? I am very tired today and…’ ‘Did you not ask me for some work? You begged me to remember you. Never mind, I will use my scenographer.’ ‘No, no, I was only saying I was tired and that you gave me very little time. But it’s all right, Mr. Leonidoff, thank you. I will be here tomorrow morning at eleven.’ I get home with my head and body full of noises of wheels, of beams, of trams and of subways. I feel more downhearted than ever. I wake up my wife and say to her, ‘dress yourself, make me some tea and some coffee, I also need a sandwich’.… The next morning, I am punctual at the Roxy. The sketches are all right. I cash a fat wad of dollars and return home, happy for the fulfilled order and blessing the metropolitan heaven of New York!” Depero, So I Think, 110–111.

- Quoted here from Depero, So I Think, 109–110.

- Günter Berghaus, Futurism and Politics, 290–307. Depero himself somehow acknowledged this aspect of his personality when he wrote, in the foreword to the English edition of his autobiography, “I cannot help thinking that a writer or an artist should, from time to time, dedicate some of his works to those people and hostile forces which have constantly humiliated, grieved and exasperated him during his life, who have gently and with delicate cunning tried to make him stumble in every circumstance and misunderstand and misrepresent his expressions and work.” Depero, So I Think, I.

- Depero’s articles on New York include: “Il futurismo negli Stati Uniti: L’opera di Depero esaltata dalla stampa americana. L’attività dell’artista a New York,” L’Impero (August 8, 1929); “New York: impressioni vissute” [New York: Lived Impressions], Numero unico futurista Campari (Milan: Campari, 1931), 39–44; “A zig zag per la Va Avenue” [Zigzag along 5th Avenue], La Sera (August 24, 1931); “Fuoocoo – Con Massine all’Auditorium – Un delinquente a sei anni” [Fiiree – With Massine at the Auditorium – a Six-Year Offender], La Sera (September 2, 1931); “Corteo pubblicitario ‘Macy'” [Macy’s Advertising Procession], La Sera (September 23, 1931); “La questione ‘vino'” [The ‘Wine’ Question], La Sera (September 30, 1931); “Traversata Atlantica” [Atlantic Crossing], La Sera (October 21, 1931); “Fuori New York – Torto, Polento, Ticcio, Pasto – Una giornalista italo-americana” [Outside New York – Torto, Polento, Ticcio, Pasto – An Italian-American Journalist], La Sera (November 23, 1931); “Ristorante cinese in Broadway – Un ingegnere giapponese” [Chinese Restaurant on Broadway – A Japanese Engineer], La Sera (December 2, 1931); “Itinerario giornaliero di un professionista newyorkese – Una segretaria ideale” [Daily Itinerary of a New York Professional – An Ideal Secretary], La Sera (January 22, 1932); “Un portiere – Primo quadro: la ballerina di cenci – ‘The Black King’ – Coniugi mulatti in calesse” [A Goalkeeper – First Act: The Ballerina in Rags – ‘The Black King’ – Mulatto Couple in a Buggy], La Sera (June 7, 1932); “Subway – Tavola parolibera,” Futurismo 1932 (Rovereto: Mercurio, 1932), 99; “New York Film Vissuto” [New York – A Lived Film], Futurismo 1932 (Rovereto: Mercurio, 1932), 105–107; “New York come l’ho vista io” [New York as I Have Seen It], Il Secolo XX 32, 7 (February 18, 1933); “N(enne) E (e) W (vi doppio)” [(e)N E (e) W (double u)], Liriche radiofoniche [Radio Poems] (Milan: G. Morreale, 1934), 75–80; “Vertigini di Nuova York” [New York Dizziness], L’Illustrazione Italiana (June 23, 1935): 1051–1052.

- See Chiesa, “Transnational Multimedia.”

- The book was to include three-hundred pages of text, twenty pages of coated pages for the illustrations, and two audio discs. These were the characteristics that Depero specified in an undated document, “New York Nuova Babele Film Vissuto,” hand-written by Depero and found at the Mattioli Archive.

- De Chirico’s memoirs also included a section dedicated to his trip to New York.

- Umberto Eco, “Il modello Americano,” in Umberto Eco, Gian Paolo Ceserani, and Beniamino Placido, eds., La riscoperta dell’America (Bari: Laterza, 1984), 3–32.

- Cesare Pavese, “Ieri e oggi,” L’Unità (August 3, 1947), reprinted and translated into English as “Yesterday and Today,” in American Literature: Essays and Opinions, trans. Edwin Fussell (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970), 196–199. The original text: “A questo punto la cultura americana divenne per noi qualcosa di molto serio e prezioso, divenne una sorta di grande laboratorio dove con altra libertà e altri mezzi si perseguiva lo stesso compito di creare un gusto, uno stile, un mondo moderno che, forse con minore immediatezza ma con altrettanta caparbia volontà, i migliori tra noi perseguivano.… La cultura americana ci permise in quegli anni di vedere svolgersi come su uno schermo gigante il nostro stesso dramma.”

- Emilio Gentile, “Impending Modernity: Fascism and the Ambivalent Image of the United States,” Journal of Contemporary History, 28, 1 (January 1993): 7. On the historical roots of this phenomenon see Claudia Dall’Osso, Voglia d’America: il mito americano in Italia tra Otto e Novecento (Rome: Donzelli, 2007).

- Vittorio Mussolini, quoted in Eco, Ceserani and Placidi, La riscoperta dell’America, 8.

- For this quote see Anna Maria Torriglia, Broken Time Fragmented Space: A Cultural Map for Postwar Italy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), 85–86.

- The importance of America in the Italian debate was, in fact, prominent at least from the late nineteenth century, as shown by Dall’Osso, Voglia d’America. But the identification of the American Myth as a theatre for Italian modernity was a characteristic of the 1930s and Depero was a pioneer in it.

- See Iain Boyd Whyte, “Futurist Architecture,” in International Futurism in Arts and Literature, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: de Gruyter, 2000), 364. In his 1914 manifesto Architettura Futurista, Boccioni wrote: “Oggi cominciamo ad avere intorno a noi un ambiente architettonico che si sviluppa in tutti i sensi: dai luminosi sotterranei dei grandi magazzini dai diversi piani di tunnel delle ferrovie metropolitane alla salita gigantesca dei grattanuvole americani” [Now around us we see the beginnings of an architectural environment that develops in every direction: from voluminous basements of large department stores, from the several levels of the tunnels of the underground railways to the gigantic upward thrust of American skyscrapers]. Quoted from Mary Ann Caws, ed., City Images: Perspectives from Literature, Philosophy, and Film (New York: Gordon and Breach, 1991), 224.

- Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero, “The Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe,” in Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman, eds., Futurism: An Anthology (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 209.

- Letter to Gerardo Dottori, n.d. (1929), published in Massimo Duranti, Dottori: Futurist Aeropainter, exh. cat. (Perugia: Effe, 1998), 10. Original: “Ma credilo New-York é una metropoli creata da diavolo per una umanità indiavolotissima.” Depero wrote to his friend and patron, Gianni Mattioli: “ci vogliono testicoli imbullonati per abituarsi al ritmo inaudito di questa metropolis di ferro e di ardimento.” Undated letter postmarked December 7, 1928 (Mattioli Archive).

- Salaris, Fortunato Depero, 55. “Parlare in fretta, salutare in fretta, visitare in fretta, affari in fretta, vestirsi in fretta, bagno in fretta. Una lettera, tre lettere, cento lettere tutte in fretta. Conversazioni sempre interrotte e tutte affrettate. Telefonate all’infinito. Media di telefonate giornaliere a N.Y. ventidue milioni. Uscire di casa in fretta. Prendere un treno elevato in fretta. Discendere nella ‘subway’ in fretta. Traversare le strade affollatissime in fretta, mangiare in fretta. Finalmente la domenica scampagnata… forse tranquilla!”

- Salaris, Fortunato Depero, 42. Original: “con inauditi sforzi mi sradico dalla folla e mi avvio a casa. Non ne posso più. Ancora negozi che mi si avventano alla faccia, ancora grattacieli che mi pesano sulla testa, ancora parole-luci che mi accecano.”

- This thesis is further supported in Chiesa, “Transnational Multimedia.”

- Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere, 292. Quoted here from Depero, So I Think, 139–140.

- See, for example, Ester Coen, “We Will Sing of Great Crowds = Canteremo le grandi folle,” in Faces in the Crowd: Picturing Modern Life from Manet to Today, ed. Iwona Blazwick (Milan: Skira, 2004), 34–39; and Christine Poggi, “Folla/Follia: Futurism and the Crowd,” Critical Inquiry 28, 3 (Spring 2002): 709–748.

- Depero to Marinetti (September 1929), quoted in Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 253. Original: “Ogni anno l’americano rinnova la casa – distrugge con una facilità impressionante. Gente volubile, capricciosa – qualità eccellenti per progredire e tenere il mercato in effervescenza.” The translation is mine.

- “Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria.” in Numero unico futurista Campari (Milan: Campari, 1931), 19–21. Reprinted as “Manifesto: Arte pubblicitaria futurista,” Futurismo 1, 2 (June 1932): 4.

- “A New York City nel 1928,” in Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 244. Original: “Porteró laggiú l’opera mia non solamente decorativa ma quella di maggior importanza i quadri.” The translation is mine.

- In Solaris, Fortunato Depero, 33. Original: “ho la sensazione di viaggiare con un carico pericoloso, considero questi dipinti come bombe concentrate di esplosioni policrome. Sarà mia intima gioia lanciarle contro i cupi parallelepipedi di questa babele.”

- For a different interpretation of these images, see David Leiber, “The Socialization of Art,” in Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 88–117.

- He wrote to his friend and collector, Gianni Mattioli: “I am buying the first machine for the production of cushions and tapestries. It’s magnificent; it sews a cushion in 10 minutes – (it would take two days by hand).” Depero to Mattioli, New York (October 5, 1929). In Depero, Depero futurista, 152.

- Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere, 270–273.

- The Museum of Modern Art opened to the public on November 7, 1929.

- Quarterly Brochure, 2 (December 1928–January 1929): 20–27. The article reproduced four photographs from Depero Futurista: three illustrating the 1927 pavilion at the Fiera del Libro in Monza, and one of his model for Architettura Fascista. Marcel Duchamp, one of the Société’s leading figures, was likely impressed by Depero’s use of the ‘Bolted Book’ as a portable museum, and possibly had that in mind in 1935 when he started his project of the Box in a Valise. In a note, entitled “Miss Katherine Dreier,” Depero acknowledged her as the main organizer of the Guarino show, mentions the Quarterly Brochure publication, and describes her as a central figure in the New York art world, “There is no artistic event where the mighty silhouette of Miss Dreier does not dominate… She enjoys the sympathy and gratitude of all of the artists, from every nationality. She establishes relationships between artists; indicates to them American methods to succeed.” The fact that this note was not published by Depero, however, confirms the scarce importance that he gave to this figure in his operation of myth-construction. See Salaris, Fortunato Depero, 136.

- He dedicated an article in the Italian newspaper La Sera (September 23, 1931) and an entire chapter of his memoirs Fortunato Depero nelle opere to the magazine, “I magazzini Macy fanno sempre le cose in grande stile. Come dicevo nella prima puntata, essi vantano 10,000 girls di servizio, le quali hanno per loro conto una propria Rivista illustrate ‘Sparks’ (Scintille), per la quale, anzi, ebbi l’incarico di disegnare copertine” (239). Only one cover designed by Depero for Sparks is actually known, from the 1930 edition, published in Belli, Depero futurista, 172.

- “Bambini Attori” in Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere, 307; “Torto, polento, ticcio, pasto,” in La Sera (November 23, 1931). Published in Solaris, Fortunato Depero, 123–125.

- Depero’s prominent example was the pavilion for the publishing house Bestetti-Tumminelli-Treves at the Monza book fair of 1927, whose structure was composed by three-dimensional letters, coherently with the publisher’s activity. His manifesto Architettura Pubblicitaria featured in his ‘Bolted Book’ of 1927.

- Depero, Fortunato Depero nelle opere, 306.

- Fortunato Depero, “Il Futurismo a New York,” handwritten document reproduced in Scudiero and Leiber, Depero futurista, 260. Original: “I grattacieli offrono prospettive audacissime, solo ingombre di meccanismi pubblicitari e luminosi … réclame esuberanti ed enormi. Luci che piovono, scoppiano e girono vertiginosamente, trascinando la fiumana di folla in un ritmico flusso e riflusso di mille colori.” The translation is mine.

- See Giovanna Ginex, “Not Just Campari! Depero and Advertising,” in Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, eds. Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, exh. cat. (Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014), 309–316; now also published here

- In the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro, Marinetti presented an Italian movement that did not exist yet; in Italy, he consistently exaggerated the successes of Futurism in Paris, London, Berlin, etc. On Marinetti’s ability to inflate or alter information see Emily Braun, “Vulgarians at the Gate,” in Boccioni’s Materia, ed. Laura Mattioli Rossi (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2004), 1–21.

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, XVIII Esposizione Biennale internazionale d’arte (Venice, Italy: Biennale di Venezia, 1932), 169. “I trionfi di Depero nell’ America del Nord” is also the title of a 1929 article in an unidentified newspaper, preserved in the Depero Archive in Rovereto. I thank Günter Berghaus for signaling the latter. In a letter to Marinetti Depero wrote: “Ho ricevuto lettera da Balla dove mi dice che nelle tue conferenze parli della mia attività Americana.” Depero to Marinetti (January 13, 1929).

- Depero, So I Think, III.

- I have explored the rhetoric of rebirth in the dialogue between Italy and the United States in Raffaele Bedarida, “Operation Renaissance: Italian Art at MoMA, 1940–1949,” Oxford Art Journal 35, 2 (June 2012): 147–169.

- Cesare Pavese, “Ieri e oggi,”L’Unità (August 3, 1947): 3.

- Carlo Levi, “Italy’s Myth of America,” Life 23, 1 (July 7, 1947): 84, 89–95.

- See Laura Mattioli Rossi, “The Collection of Gianni Mattioli from 1943 to 1953,” in The Mattioli Collection: Masterpieces of the Italian Avant-garde, ed. Flavio Fergonzi (Milan: Skira; London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 23–26, 57.

- Fortunato Depero, A passo romano: lirismo fascista e guerriero programmatico e costruttivo (Trento: Edizioni Credere Obbedire Combattere, 1943).

- A trope in his letters from the United States between 1947 and 1949 is the fear that Communism would take over in Italy, only relieved after the victory of the Christian Democracy party in the general elections of April 1948. See Michele Ruele, ed., Depero: Lettere inedite dagli USA e arazzi della collezione ITAS (Rovereto: Via della Terra, 2004).

- Depero, So I Think, 159.

- Depero explained to his friend and patron Guglielmo Macconi that, as an Italian, he encountered hostility in America “for political reasons.” See Depero to Macconi (June 4, 1948), in Ruele, Depero: Lettere inedite, 16.

- Alfred Barr had included a section on Futurism in his influential show, Cubism and Abstract Art held at MoMA in 1936. His dismissive art historical evaluation of Futurism was widely shared in America. In the catalogue, he justified the movement’s presence in the show not in terms of quality but of influence, as if he had to include it: “Although the artistic value of the Futurist movement is debatable, its influence upon European art of the following decade was second only to that of Cubism.” But then he added, not without sarcasm: “The Winged Victory of Samothrace, which Marinetti found less beautiful than a speeding automobile, still holds its own against Boccioni’s Forme Uniche di Continuità nello Spazio, and the speeding automobile itself is perhaps a finer Futurist work of art than Russolo’s Dinamismo (automobile).” Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Cubism and Abstract Art (New York: MoMa, 1936), 61.

- On the MoMA show and its history see Bedarida, “Operation Renaissance.”

- See Fabio Belloni, “The Critical Fortune and Artistic Recognition of the Work of Depero,” in Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, eds. Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, exh. cat. (Madrid: Madrid-Fundación Juan March, 2014), 349; now also published here.

- Depero’s affiliation with Futurism started as early as 1913, but it was not until the publication of his manifesto, Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe in 1915 that he became a prominent voice within the movement.

- Depero to Guglielmo Macconi (August 25, 1948), in Ruele, Depero: Lettere inedite, 27.

- Depero to Guglielmo Macconi (July 30, 1948), in Ruele, Depero: Lettere inedite, 24.

- On Depero’s posthumous fortune, see Fabio Belloni, “The Critical Fortune.” Gabriella Belli has produced a rigorous body of scholarship based on documentary evidence. The author Maurizio Scudiero, on the other hand, has embraced Depero’s accounts as truthful in an overwhelming number of publications. As a result, at historians’ perception of Depero’s success in America is often exaggerated. For one, Fabio Benzi has suggested that the project for the Chrysler building in New York was changed from the original “neo-Byzantine” style because of Depero’s influence. See Fabio Benzi, Art Déco (London: Taylor & Francis, 2004), 40. A similar statement, which is uniquely based on the chronological concurrence of Depero’s stay in New York and the evolution of that architectural project, gives the measure of how inflated is the perception of Depero’s impact on the New York art scene.

- See note six for a list of publications focusing on Depero in New York. An exemplary case is Depero’s 1930 sketch for the scenography for The New Babel, featuring skyscrapers, Broadway ads, subway tunnels, and big signature, “Depero New York,” reproduced in countless publications, it has been used to illustrate the covers of Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arco, ed., Depero, exh. cat. (Milan: Electa, 1989) and Belli, Depero futurista; and in 2014, it was reproduced in the invitation card of the Solomon R. Guggenheim survey, Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe. Such an iconic status is rare for any futurist work post–1915 and is particularly striking as the sketch for a rejected theatrical project.