Stitching Modernity: The Textile Work of Fortunato Depero

Virginia Gardner Troy Virginia Gardner Troy Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/depero/

Fortunato Depero (1892–1960) was a Futurist artist who worked in a variety of artistic mediums, from painting and graphic design to furniture and textiles. His work in textiles, created and produced in close collaboration with his wife, Rosetta Amadori, can be considered the most important development in his artistic career, as it comprised a large portion of his creative production. Yet, this work has largely been overlooked. This oversight can be explained by many factors, including inconsistencies in categorization – for example, his textiles have been described as embroidery, needlework, tapestry, patchwork, and cloth mosaic – and the persistent relegation of textiles to the realm of crafts and domestic arts rather than art. This second state of affairs, in particular, has led scholars and conservators of Futurism to neglect the artist’s work in textiles. This paper will place Depero’s textiles within the context of early twentieth-century modern artistic activities, and demonstrate the centrality of this work to his oeuvre.

Fortunato Depero’s (1892–1960) discovery of textiles as a modern art form can be considered the most important development in his artistic career.1 It occurred between 1917 and 1919, when he and his wife, Rosetta Amadori, experimented with fabric constructions and realized that their textile creations, which he referred to interchangeably as “cloth mosaics” and “tapestries” (arazzi), could be the key to their financial and artistic success. Though they are not technically tapestries, the description has remained.2

The story of Depero’s epiphany with cloth mosaics comes primarily from his 1940 autobiography, So I Think, So I Paint, and is augmented by contemporary accounts of his pivotal years in Rome, Capri, and Viareggio from 1913 to 1919, when the war pushed artists into both isolation and pockets of creative collaboration. During this critical time he became a member of the Futurist movement, co-wrote a manifesto with Giacomo Balla, entitled Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo (Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe; 1915), and designed and produced sets and costumes for a ballet staged by Serge Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes (1909–1926).3 Textiles played a significant role in these endeavors. In the manifesto, for example, the artists called for the creation of dynamic and joyful constructions using all kinds of materials, including cotton, wool, silk, and ‘gaudy material,’ in order to transform and reconstruct the status quo by assaulting the senses with bold colors and shapes.4 As Depero worked on the designs for Diaghilev’s 1916 staging of The Song of the Nightingale ballet, he utilized materials at hand for the mock-up designs, such as pieces of fabric and colored paper cut and glued to cardboard, recalling,

this was an elementary technique I used in order to economize [materials] and, in a short time, I had become quite good at using my scissors and cutting out flowers, animals and figures of all kind, and in pasting the smallest pieces.5

as seen in his 1916 collage, Costume per Mandarino (Costume for the Mandarine), a main character of the ballet.6 While Depero’s work for The Song of the Nightingale was not brought to production, his work in Rome put him into contact with some of the most significant avant-garde innovators of the era. Importantly, he left Rome in 1917 with a stash of brightly hued wool felt that Diaghilev had brought from Spain; this fabric became the material that solidified his theories about art in the modern age, thanks, he wrote, “to Rosetta’s diligent and loving co-operation.”7 Over the next two years they worked in collaboration to find a balance that united abstract forms with handmade production through their easel-sized tapestries.

Inspired by his paper collage work, these early tapestries were cloth versions of some of his ballet designs, such as the 1919 tapestry, Mandarino con ombrello (Mandarino with Umbrella). He documented his and Rosetta’s collaboration in his 1919 painting, Io e mia moglie (My Wife and I), portraying himself as the designer at his easel and depicting Rosetta as the stitcher at her frame, both seemingly content in their roles. Depero pronounced their work a triumphant success: “The fairy dream of my tapestries was born and realized,” he wrote, “I happily dance around, I radiate gaiety. I am convinced I have found a practical solution for an unexpected and easy future.”8 In 1919, they moved back to their hometown of Rovereto to establish a workshop and showroom for their new enterprise, the Casa d’Arte Futurista (The House of Futurist Art).

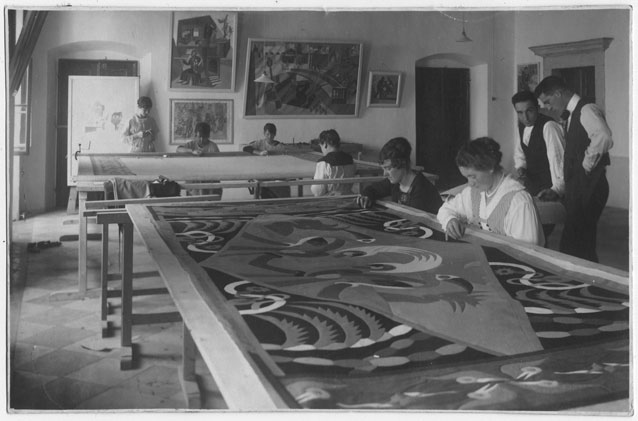

Depero was fortunate in that he had access to an immediate, in-house, skilled labor pool of textile crafters, due to Rosetta’s stitching and management skills, seen in this 1920 photograph of their workshop (figure 1); Depero’s cartoons served as pattern templates, with colors apparently chosen collaboratively with Rosetta.9 There they created his first large-scale tapestry, Cavalcata fantastica (Fantastical Ride; 1920; figure 2), commissioned by Milanese publisher Umberto Notari, which reveals his ‘fairy dream’ through the use of colorful, fantastic, and multi-limbed figures and animals framed by a border of bilaterally placed birds and fish and a checkerboard edge.10 This ambitious and very large work (approximately 9 x 12 feet) served as an ideal alternative to painting, as its tactile surface and dynamic imagery satisfied Depero’s quest to create art that appealed to the senses. Depero described his tapestries as “rainbow-like beverages for the eyes.”11

Collage

Collage was an essential technique for Depero and for the development of modern art and design because it presented a visual and literal fracturing and restructuring of form by eliminating shading. For artists like Pablo Picasso, collage provided an opportunity to address perceptual ambiguity and contradiction between the objects represented and the unrelated materials used to create them, such as his use of newspaper to represent the neck of a man in Head of Man with Hat (1912). For the Futurists, collage allowed them to create dynamic, forceful, sharply geometric compositions that represented ‘force lines,’ as in Balla’s work. For Sonia Delaunay, who exhibited collage book covers at the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon (First German Autumn Salon) in 1913, alongside the work of many Futurists, collage proved to be a versatile technique that could translate to various uses and media, such as for book designs, advertisements, and costumes. She used collage most expertly in her Simultaneous Robe of 1913 by transforming fabric pieces into a three-dimensional wearable construction.

Theatrical Costumes

Through his work with Diaghilev, Depero met the Russian artist Natalia Goncharova, and worked with Picasso on the costumes for the 1917 production of Parade.12 She designed numerous costumes for Diaghilev such as the Sea Prince for the 1916 staging of Sadko: In the Underwater Kingdom, which was made from luxurious fabric such as silks, velvets, and metallics, pieced together with appliqué and embroidery. Similarly, Picasso’s Chinese Conjurer costume for Parade, was created from pieced and appliquéd cloth in highly contrasting shapes and hues to intensify the visual dynamism and make the figure appear larger than life. Depero would have known about these innovations in textiles and would have been impressed with the way fabric collage could activate three-dimensional space.

Intarsia and Cloth Patchwork

The impact of intarsia on Depero’s work was also significant due to his early (circa 1910–1913) experience as a stone mason and sculptor’s apprentice in Rovereto and Turin during which he may have been exposed to stone and wood intarsia techniques.13 Intarsia is prized in Italy, with the wood intarsia (also referred to as marquetry) studiolo of Frederico de Montefeltro in Umbria and the marble floor inlay (also referred to as pietre dure) of St. Peter’s Basilica serving as famous examples. Indeed, he compared his tapestries to this respected tradition, writing that his “cloth mosaics of plastic [three-dimensional] volume are modernizations of stone and Byzantine examples.”14

Depero’s cloth mosaics are part of a larger history of felted wool cloth patchwork constructions in Europe. Meticulously pieced wool wall hangings and banners were prized in Europe before the industrial revolution as examples of both a tailor’s skill in stitching and cutting, and as documents of nationalistic and political events through the re-purposing of wool military uniforms.15 For example, an eighteenth-century hanging from Eastern Europe at the Museum of Folk Art in Vienna, which was most likely made from uniform off-cuts, shows a Tailors’ Guild Coat of Arms with an inlaid lion, scissors, and needle, surrounded by figures, columns, scrolls, and a border of flowers.16 Similarly, a Swiss wall hanging commemorating Napoleon’s 1812 military defeat was made from military uniform pieces and regiment badges meticulously stitched to form a radiating pattern around an “Eye of Providence.”17 Rosetta and Depero were from Rovereto, which until 1914 was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; Depero’s father was a gendarme in the Austro-Hungarian Imperial troops, for which military uniforms and inlaid military banners were important.18 They were most likely aware of such examples of cloth patchwork.

In Europe, military uniforms were made of wool, preferably felted wool for its warmth, resistance to shrinkage, and versatility. Felt is produced through a process by which wool cloth or wool fibers are moistened and matted in order to tightly bind the fibers together. As a result, the edges, when cut, do not fray.19 Felted wool has a soft texture, firm density, is lightweight, and retains vivid hues. Felted wool has no nap direction – there is no particular direction of the raised fibers, as in velvet for example – so irregular pieces of felt can be pieced together economically without visible seam lines.20 Depero and Rosetta used this piecing technique in one of their first cloth inlay pieces, Young Girl with Sailor (1917), in which irregular sections of the green background and purple body of the sailor have been pieced. By this time they had also devised a technique whereby the stitching thread color matched the fabric color in order to create smooth joins.21

Diverse Visual Sources

Depero’s Casa d’Arte developed during the golden age of artistic multimedia experimentation in the arts, within the first three decades of the twentieth century. The boundaries separating fine from applied arts were, for a magical moment, blurred and disregarded, which accommodated a range of activities and a range of players, including women. This led to a rising interest in handcrafted textiles from many epochs, from many cultures, and in many forms: woven, embroidered, pieced, cross-stitched, and printed. In a 1921 exhibition catalogue, Depero wrote that he sought to

materialize the entire universe as manifested in its various climates, geography, dawns and dark nights of the soul, in this way returning to the spirit of the true work of art and re-establishing contact with all the great art of the past. Eastern and Western, ancient and modern.22

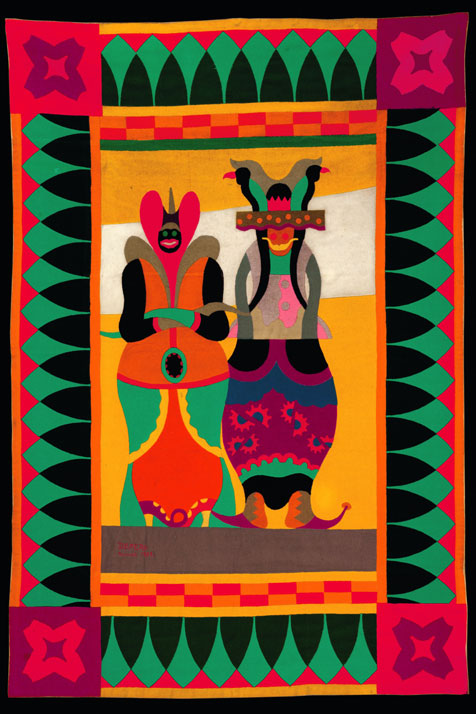

In Depero’s tapestries, one can see that he and Rosetta were aware of a range of textile traditions, as well as European and Russian folk art designs, which they appropriated to suit their goals to create joyful, colorful, and fantastic decorations, seen in the 1920 tapestry, Due maschere tropicali (Two Tropical Masks; figure 3), a hybrid of Asian and South American motifs.

Applied Arts Reform

Depero’s Casa was but one of many notable multimedia endeavors of the early twentieth century that united textiles art, and consumer culture through showrooms and advertising. One of the first was the Wiener Werkstatte (1903–1932), famous for its printed fabrics. This trend continued through the first two decades of the twentieth century with Roger Fry’s Omega Workshop in London (1913–1919), Paul Poiret’s Maison Martine in Paris (1911–1925), Sonia Delaunay’s Simultaneous Boutiques in Madrid and Paris (1920s), and Marie Cuttoli’s Maison Myrbor (1922–1936) for whom Goncharova designed appliquéd and embroidered fabric clothing.24 In Italy, Depero’s colleague Enrico Prampolini opened his Casa d’Arte in Rome in 1918, highlighting fabrics and other applied arts; and Balla opened his home, Casa Balla Futurista, to visitors around the same time.25

Interestingly, Depero’s Casa was established the same year as the Bauhaus school (1919–1933), and in the early years they shared similar goals to equalize art and craft, and to replace historicist clutter with designs and objects that reflected modern life. For members of the Bauhaus, attempts to unite art, handcraft, and industry involved designing prototypes for industrial production and moving from unique expression to anonymous production. For Depero’s “art industry,” as he referred to his Casa, it involved buying a sewing machine to streamline production, despite noting that the sewing machine was useful when stitching straight pieces together, but not as useful for curved shapes.26 Exactly how the sewing machine was implemented and whether or not there was a zigzag attachment remains to be examined. While the use of a sewing machine would have bolstered his Futurist embrace of mechanization, it also partially removed the aura of handcraftedness that he cherished and cultivated.

This paradox, as well as the eccentric imagery and bold color combinations of his tapestries, might explain some of the reasons why his textile work was not fully embraced or understood by American audiences during his time in New York City from 1928 to 1930. America was on the cusp of massive changes to the textile industry, moving from wool and cotton production to synthetic fiber; Depero’s hybrid handmade and machine-sewn textile work resembled neither traditional American textiles such as quilts, nor the manufactured cloth that was fashionable at the time. Depero later reflected that if his tapestries had “been calmer” with “softer tones and less contrast,” he could have sold more.27 While this would have been an opportune time to sell his designs to textile manufacturers in the US, he returned to Rovereto in 1930 apparently without having pursued those possibilities.

In the 1930s, with limited opportunities to promote and sell his textiles to an international market, Depero focused his textile work on stylized heraldic and nationalistic icons, including traditional costumes and emblems like eagles and goats (caproni), for a few major Italian patrons, including aviation pioneer Gianni Caproni, for whom he created a goat and stylized eagle tapestry. The playful and fantastic forms and colors associated with his earlier tapestries decreased in favor of more neutral colors and orderly, symmetrical compositions.28

Conclusion

Depero’s confidence that textiles could reconstruct his career and change the direction of modern art was based on an interrelated set of factors that positioned him at an ideal place and time to pursue the craft of cloth mosaics. He was part of a rising tide of practitioners and supporters of applied arts in modernist circles who advanced and expanded the role of textiles in art and design. Textiles served as an ideal gateway to abstraction and fulfilled his artistic ambitions for collaborative and multimedia innovation.

His work in textiles pushed him to approach design and composition in new ways by focusing on graphic and tactile possibilities, which ultimately informed his work in all media. He referenced his textile work in advertisements, such as for promotional posters for the Casa d’Arte; in graphic design, such as for a proposed cover of Vanity Fair magazine; and in painting, such as Embroiderer and Reader (1920) and The Embroiderer (1922), which was based on an earlier tapestry, The Needleworker (1921), both featuring a large wooden bobbin. Through textiles, Depero and Rosetta merged tradition with modernity, art and craft, and lived, for a brief time, the ‘fairy dream’ of an ideal world.

Bibliography

Belli, Gabriella, ed. Depero futurista: Rome – Paris – New York, 1915–1932 and More. Milan: Skira, 1999. Exhibition catalogue.

Bellow, Juliet. “When Art Danced with Music.” In Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909–1929, edited by Jane Pritchard, 187–202. London: V&A Publishing, 2013.

Bontivoglio, Mirella and Franca Zoccoli. Women Artists of Italian Futurism. New York: Midmarch Press, 1997.

Bosoni, Giampiero, ed. Il Modo Italiano: Italian Design and Avant-garde in the 20th Century. Milan: Skira, 2006.

Day, Susan. Art Deco and Modernist Carpets. London: Thames & Hudson, 2002.

Depero, Fortunato. Depero e la sua casa d’arte. Rovereto: Mercurio, 1921. Exhibition catalogue.

Depero, Fortunato. So I Think, So I Paint: Ideologies of an Italian Self-made Painter. Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1947.

Richardson, John. A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years 1917–1932. New York: Knopf, 2007.

Scudiero, Maurizio. Fortunato Depero, Stoffe Futuriste. Trento: Manfrini Editori, 1995.

Tietmeyer, Elisabeth, ed. Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis Heute. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2009.

Troy, Virginia Gardner. The Modernist Textile: Europe and America 1890–1940. London: Lund Humphries, 2006.

How to cite

Virginia Gardner Troy, “Stitching Modernity: The Texile Work of Fortunato Depero,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/depero-troy/, accessed [insert date].

- This paper is a version of a presentation delivered for a symposium on Fortunato Depero at the Center for Italian Modern Art, New York, February 21, 2014. I am grateful to Laura Mattioli, President, and Heather Ewing, Executive Director (2013–2018), for their support.

- One of the reasons why textiles are often overlooked in historical accounts is due to inconsistencies in properly understanding and categorizing techniques. A tapestry is a weaving of warp and weft threads using a loom; Depero’s ‘tapestries’ are made from pieced and stitched fabric similar to appliqué and patchwork.

- Fortunato Depero, So I Think, So I Paint: Ideologies of an Italian Self-made Painter (Trento: Mutilati e Invalidi, 1947), 120–121; John Richardson, A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years 1917–1932 (New York: Knopf, 2007), 11–16. Depero worked with Picasso on the sets for Diaghilev’s staging of Parade (1917). From 1914 to 1929, Diaghilev travelled the major cities of Europe commissioning avant-garde artists to design costumes and sets to accompany his ballet stagings; see Juliet Bellow, “When Art Danced with Music,” in Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909–1929, ed. Jane Pritchard (London: V&A Publishing, 2013), 187–202. The manifesto was originally published in Italian as a leaflet by Direzione del Movimento Futurista on March 11, 1915, Milan.

- The notion of using aggressive force to push Italian society into the modern age was put forth in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto in 1909.

- Depero, So I Think, 120.

- Choreographed by Leonide Massine, music by Igor Stravinsky. Depero, So I Think, 120.

- Richardson, A Life of Picasso: 1917–1932, 11. Matisse eventually created the sets and costumes in 1919; Depero was recruited to create figures for Picasso’s staging of Diaghilev’s Parade (1917). Depero, So I Think, 120. While in today’s world, sewing skills are not widely taught, most girls and women of Depero’s era, including Rosetta, were trained in many types of textile techniques. These included stitching techniques such as embroidery, lacemaking, and cross-stitch, as well as tailoring techniques involving pattern construction, cutting, and piecing.

- Depero, So I Think, 120–121.

- Maurizio Scudiero, Fortunato Depero, Stoffe Futuriste (Trento: Manfrini Editori, 1995), 29–31.

- Scudiero, Fortunato Depero, 29–31.

- Mirella Bontivoglio and Franca Zoccoli, Women Artists of Italian Futurism (New York: Midmarch Press, 1997), 140.

- Richardson, A Life of Picasso: 1917–1932, 11–16.

- Gabriella Belli, ed., Depero futurista: Rome-Paris-New York, 1915–1932 and More, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 1999), 14. Sources cite differing accounts of the apprenticeship: with a stone mason, with a marble cutter, and, as Belli noted, with sculptor Pietro Canonica in Turin, all with approximate dates of circa 1910–1913.

- Depero, So I Think, 38.

- Elisabeth Tietmeyer, ed., Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis Heute (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2009), 7–16, 24–26.

- Tietmeyer, Tuchintarsien, 142–145.

- Tietmeyer, Tuchintarsien, 295–297.

- Belli, Depero Futurista, 14.

- Felted cloth refers to moistened and matted fiber; fulled cloth refers to moistened and matted woven cloth.

- Tietmeyer, Tuchintarsien, 31–33.

- Scudiero, Fortunato Depero, 29.

- Fortunato Depero, Depero e la sua casa d’arte (Rovereto: Mercurio, 1921), 5, quoted in Belli, Depero Futurista, 66.

- Scudiero, Fortunato Depero, 17–18.

- Goncharova also designed costumes for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes by 1915, and had met Depero in Rome in 1916. Richardson, A Life of Picasso: 1917–1932, 16. See Virginia Gardner Troy, The Modernist Textile: Europe and America 1890–1940 (London: Lund Humphries, 2006), 61–81 for a discussion of artistic collaborations within the context of textiles.

- Giampiero Bosoni, ed., Il Modo Italiano: Italian Design and Avant-garde in the 20th Century (Milan: Skira, 2006), 49. Susan Day, Art Deco and Modernist Carpets (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002), 81.

- Depero, So I Think, 124–125. Depero notes in his memoir that he purchased a sewing machine in 1924 or early 1925; Belli notes that he also bought a sewing machine while he was in New York in 1929. Belli, Depero Futurista, 151.

- Belli, Depero Futurista, 151–152.

- Scudiero, Fortunato Depero, 170.