Not Just Campari! Depero and Advertising

Giovanna Ginex Giovanna Ginex Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/depero/

In Italy, nineteenth-century réclame changed drastically to more modern forms of advertising in the early years of the twentieth century. The main architects of this revolution were the Futurists, including Fortunato Depero. However, this paper analyzes other aspects of Depero’s advertising career, starting in 1939, with a particular emphasis on his figurative sources, as well as his relationships with customers and lesser-known business contacts, such as the Milanese rubber company, Pirelli.

Today it is common to raise concerns about the ‘environmental impact’ of advertising in our lives and on the fabric of the city. Incredibly, already in 1903, the Milanese architect Luca Beltrami warned against the dangers of bright advertising columns, which he called “small annoyances of progress.”1 The people of Milan, Beltrami argued, were now used to living with publicity: on streets, on trams, in newspapers – even children’s dreams were inhabited by characters that peeped out from posters and placards. Why not, he proposed sarcastically, also use the stained glass in the cathedral for “artistic color advertisements illuminated by an electric lamp?”2

Glory to the great red advertisement, avenging nature in the archaeological and triumphing as a complement to the landscape green with rage. Glory to the great advertisements that recur, violently expressive in their often identical features, exasperating the aesthetes of Arcadia…. The yellow, red, green posters, the large black, white and blue letters, the gaudy and grotesque signs of shops, emporia, and clearance sales….3

This sentiment was echoed by Giacomo Balla and Depero in their manifesto, Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo (Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe), originally published on March 11, 1915: “Tearing up and throwing a book down into the courtyard has enabled us to intuit Phono-moto-plastic Advertising….”4 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, too, publicly defended luminous signs in an open letter to Mussolini in 1927, opposing a proposal to turn off the illuminated advertising in the Piazza del Duomo in Milan.5 “Progress,” he argued, “with the defeat of the hated nineteenth century,” covered the face of the Palazzo Carminati, in front of the Duomo, with displays – “electric moons,” Marinetti called them, as opposed to the nostalgic moon, a symbol of traditionalism (figure 2).

The revolution in the relationship between artists and advertisements brought about by Futurism changed the very definition of advertising. Futurism conceived life as a global artistic expression, collapsing barriers between high and low culture, as well as major and minor arts. In the process, entirely new creative fields became possible.

Depero’s advertising

Critics often point out that Depero overturned in one great leap the traditions of Italian advertising, which were still very nineteenth-century in their taste. This is undoubtedly correct, but it should be kept in mind that Depero’s advertising work – and in fact the entire universe of his artistic production – has deep roots in various cultural, iconographic, and visual fields.

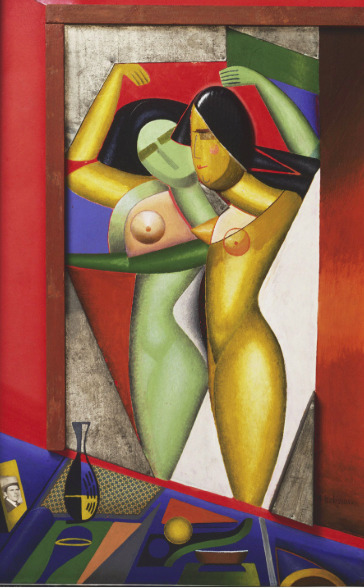

For the innovative aspects of his compositions, and especially his advertising creations, Depero owed a great debt to popular culture and to the puppet theater. He was also a keen observer of the output of Pablo Picasso and above all of Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964), who was invited to Rome in May 1914 to show several works – including Still Life, Portrait of a Lady, and Carrousel Pierrot (figure 3) – at the First International Futurist Open Exhibition, organized by Giuseppe Sprovieri in his Futurist gallery.

Sprovieri commissioned Depero to design the poster for this exhibition – as probably Depero’s first job in advertising. This was followed in 1916 by the advertisement for his own solo show in Rome, and in 1917–1918 by the billboard for Balli plastici (Plastic Ballets) at the Teatro dei Piccoli, owned by Vittorio Podrecca, in Rome (figure 4). Depero’s style in these first works is characterized by the use of colors laid in flat tones, perfect for the photo-chromolithography printing technique used in posters, and by detailed attention to the lettering. These works helped to popularize a visual style that continued to be powerfully relevant for many years, as can be seen as late as 1930 in the poster designed by Bruno Angoletta (1889–1954) for the same theater, I Piccoli (figure 5).

In looking at the influences that helped to shape Depero’s art, one must note the strong presence of Russian artists in Italy from the 1890s onward. In 1914, the Russian Pavilion opened at the eleventh Venice Biennale. In the years that followed, Depero met Russian artist Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964) – whom he later rightly accused of plagiarism – and his partner Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962), both of whom had, after immigrating to France, traveled to Rome in the spring of 1916 as part of the entourage of the impresario Sergei Diaghilev.

In 1917, Depero worked with Giacomo Balla on the stage sets for the Ballets Russes. In the April of that year, five works by Depero, alongside those of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso, and other artists, were showcased in the exhibition of the collection of the Russian choreographer and dancer Léonide Massine at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome. A few years later, in 1920, Depero visited the twelfth Venice Biennale, which featured works by both Goncharova and Larionov, as well as an important Archipenko retrospective that included a good number of his painting-sculptures (figure 6).

It is possible to see echoes of these artists’ influence in Depero’s subsequent work. In 1921, Depero traveled to Milan and then to Rome to promote his business with a show featuring the production of his Casa d’Arte. In the exhibition catalogue, a text attributed to the publisher and Depero’s patron Umberto Notari proclaims:

We have to revive the art of the billboard. We have to violently force the audience to stand on street corners in contemplation of an irresistible mural panel… in front of a billboard by the young artist from Trentino the pedestrian must linger with a cry of surprise.6

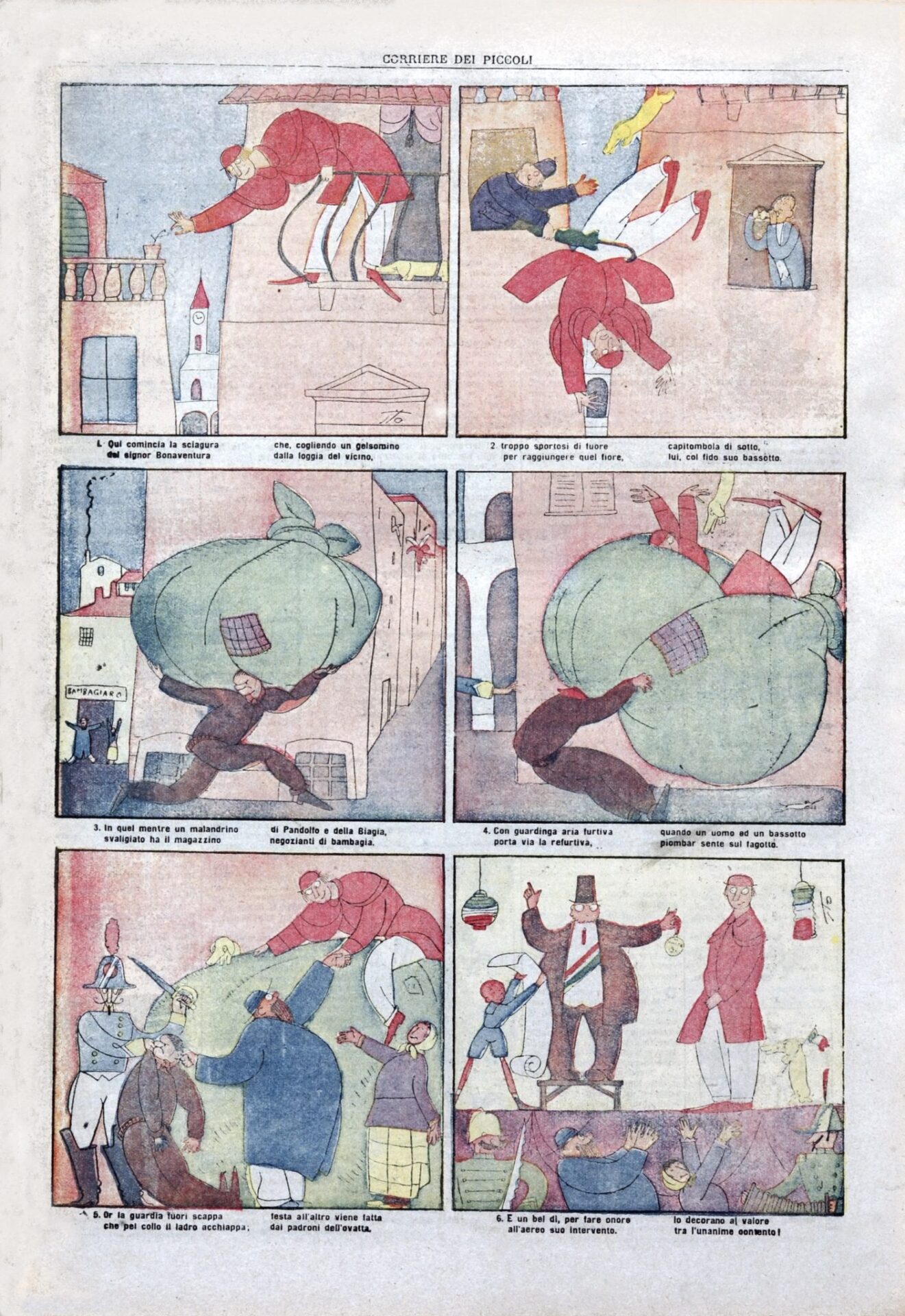

Indeed, one can find other suggestions of cross-pollinations connecting these worlds. It is interesting to compare, for instance, the inventions of Sergio Tofano (1883–1973), creator of the character of Signor Bonaventura who appeared in the children’s weekly magazine Il Corriere dei Piccoli during World War I (figure 7), alongside Depero’s clowns and other theater creations. The same synthetic touch is present even in Tofano’s fragile paper puppets.

The Casa d’Arte Futurista and the 1920s

In 1919, the young Depero opened the Casa d’Arte Futurista (The House of Futurist Art) in Rovereto. This marks a turning point in Depero’s career: from that point on, work in advertising became his most lucrative activity.

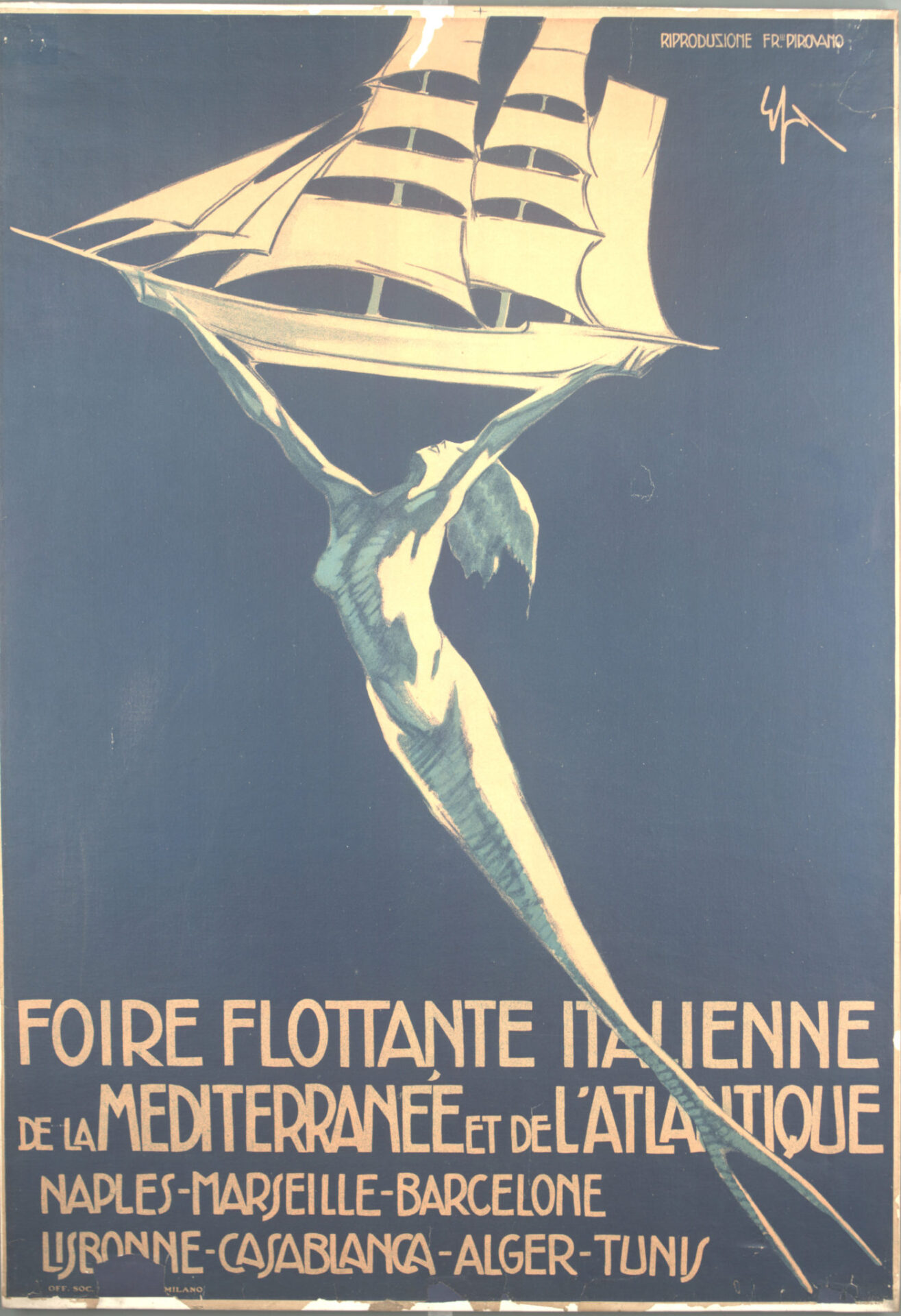

One of the first commissions Depero received was for the Foire Flottante (Floating Fair), for which he designed a series of posters in 1920 to advertise Italian products in Mediterranean and Atlantic ports (figure 8). Depero conceived the campaign for Umberto Notari’s Istituto Editoriale Italiano in Milan, publisher of Marinetti’s texts and the Futurist manifestos. The Roman painter and poster designer Enrico Sacchetti (1877–1967) worked on the same subject and went so far as to even post the billboards himself (figure 9). Comparing the proposals of these two artists is enlightening, since they illustrate the dual trends of production in Italian graphic design in the 1920s.

In 1924, the poster for the mechanized ballet Anihccam del 3000 (figure 10) – the word macchina (machine or car) spelled backwards – with stage sets and costumes designed by Depero, was perhaps the last playbill made by the artist for one of his own shows.

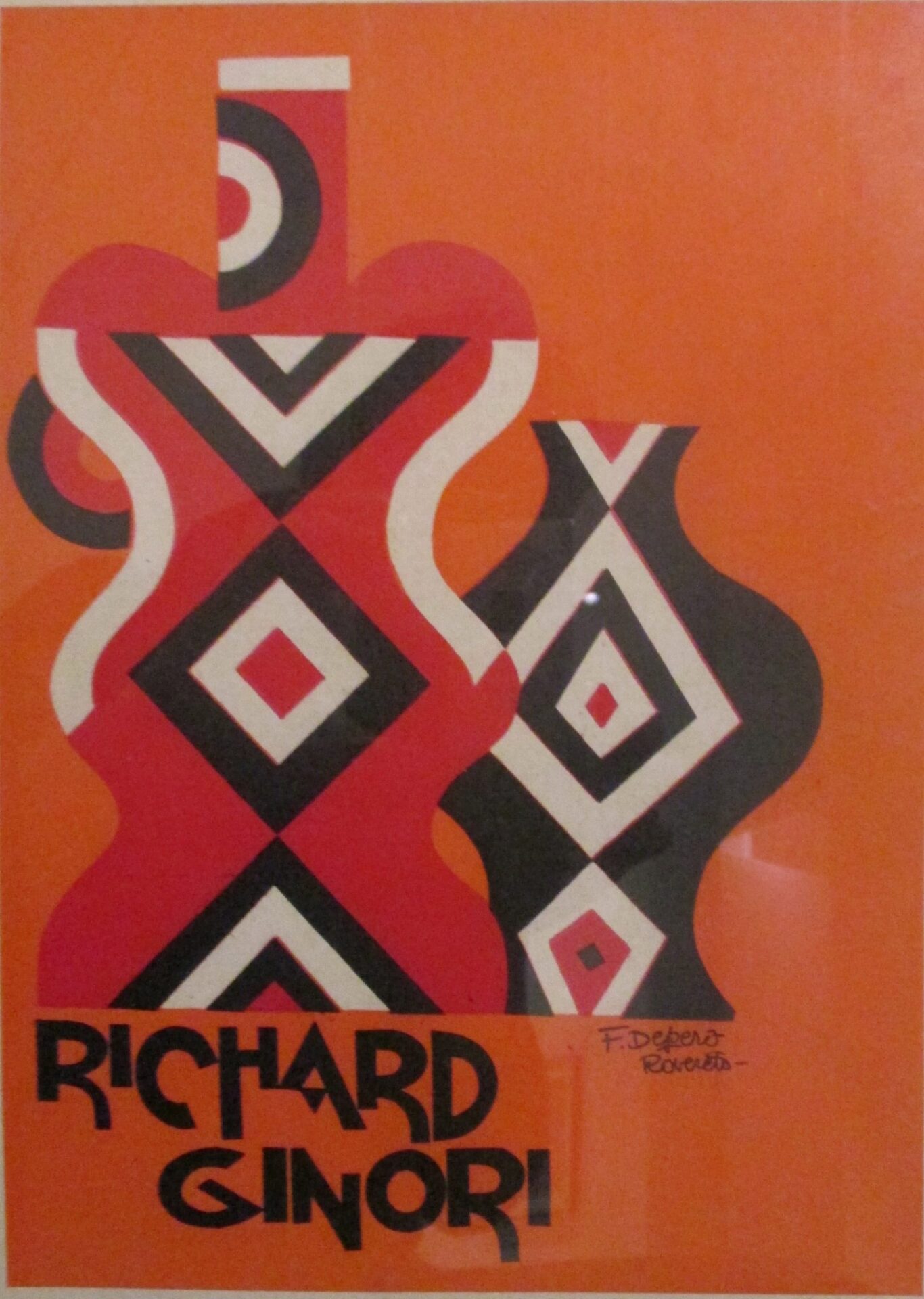

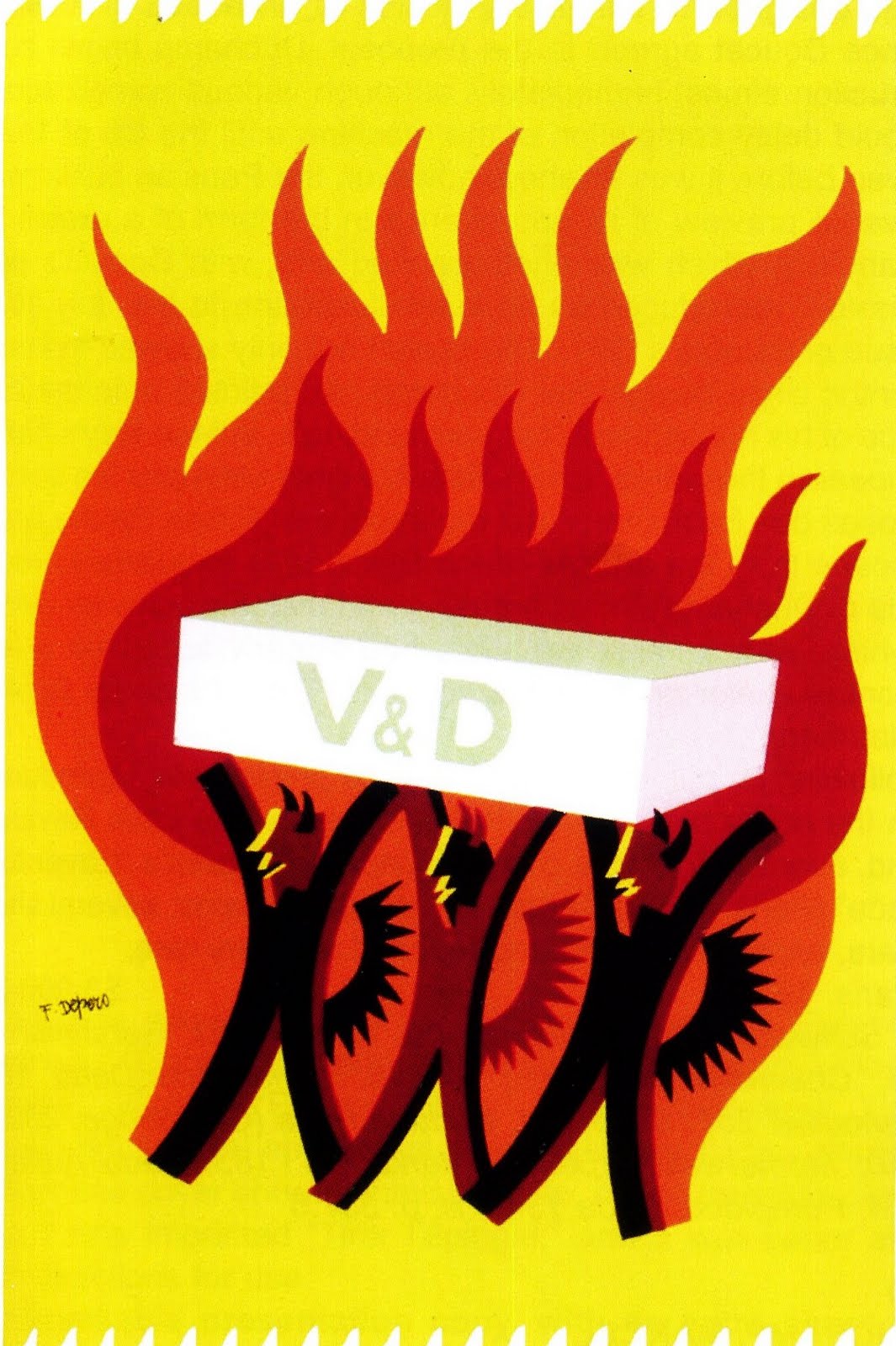

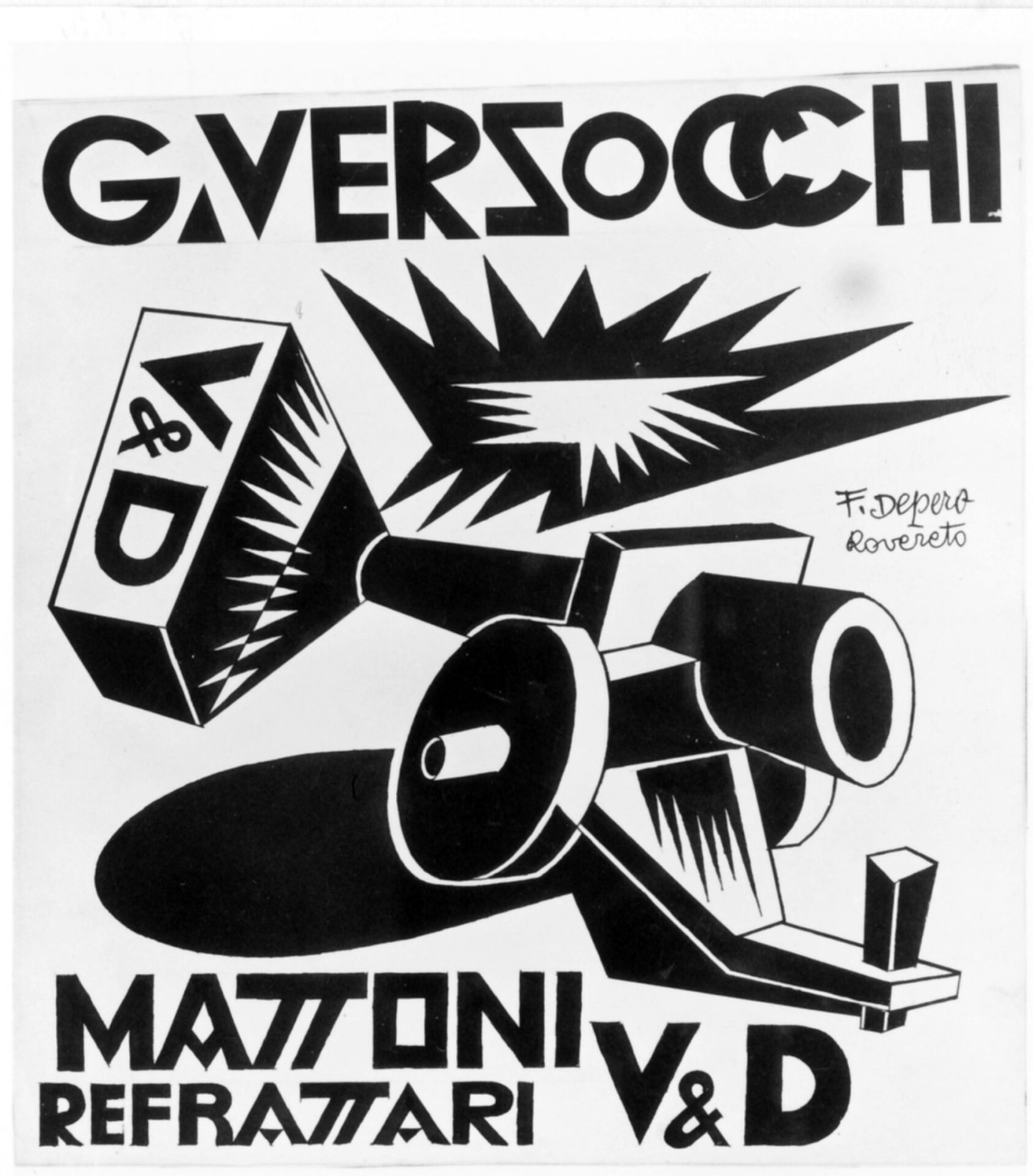

By that time, the commercial work of the Casa d’Arte had become increasingly important; in this same year, Depero received his first commissions from major Italian companies including Richard Ginori (figure 11) and Giuseppe Verzocchi (figure 12).

In fact, Depero’s first ongoing collaboration with a commercial company in the role of publicist was for Verzocchi. Together with a large group of artists, Depero worked on the illustrations of a sophisticated advertising booklet to promote Verzocchi’s production of refractory bricks (figure 13): the famous V&D, destined to become one of the most compelling examples of Fascist architecture. Depero also created posters, advertisements, designs for costume parties, and even paintings and editorials for Verzocchi. In 1950, Verzocchi and Depero organized an exhibition in Venice where art was exhibited as an extension of advertising. Each artist had to make a painting that included the image of a brick and the brand VD. Depero designed the cover for the exhibition catalogue (figure 14).7

Paris and Azari

In 1925, Paris hosted the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts). The organization of the event had started before the war and, although it was only implemented a decade later, the organizers remained faithful to the original idea, which excluded any reproduction or imitation of traditional forms. On this occasion, Depero’s work was shown not in the grandiose Italian pavilion – described at the time as a funerary chapel in the ancient Roman style – but in a small space in the Grand Palais, within an exhibition of Futurist art organized by Marinetti and alongside works by Giacomo Balla and Enrico Prampolini. Depero won several awards for this street art.

Two years later, in 1927, the artist created Depero futurista, commonly known as the libro imbullonato (‘Bolted Book;’ figure 15). This volume was conceived both as a kind of self-promotion of his first fifteen years of advertising activity and as an example of how an art object can be sponsored. Campari and Richard Ginori each bought an entire section of the book, and they also purchased many copies of the publication itself; Ginori, for instance, bought 120 copies.8

The system of financing the book through the sale of pages, which was, in itself, self-promoting and the best kind of advertising art, owes its conception to the initiative of Fedele Azari (1895–1930), an aviator, publisher, painter, poet, and well-placed member of Milan society who was Depero’s partner in the venture. In the years that followed, other Futurist artists imitated this mechanism in their dealings with companies in various fields: Marinetti did so with SNIA Viscosa,9 Farfa with Ferrania, and Nikolay Diulgheroff with Fiat.10 For all its influence and prestige, the libro imbullonato was a huge disappointment in terms of sales. “Our book was a disastrous affair,” Depero wrote to Gianni Mattioli, “except for two good sales, one made by Azari to Richard Ginori and the other by myself to Campari. Now, the book is out of date. I use them just for advertising gifts.”11 Only three years had passed since publication when Depero wrote this letter.

Campari

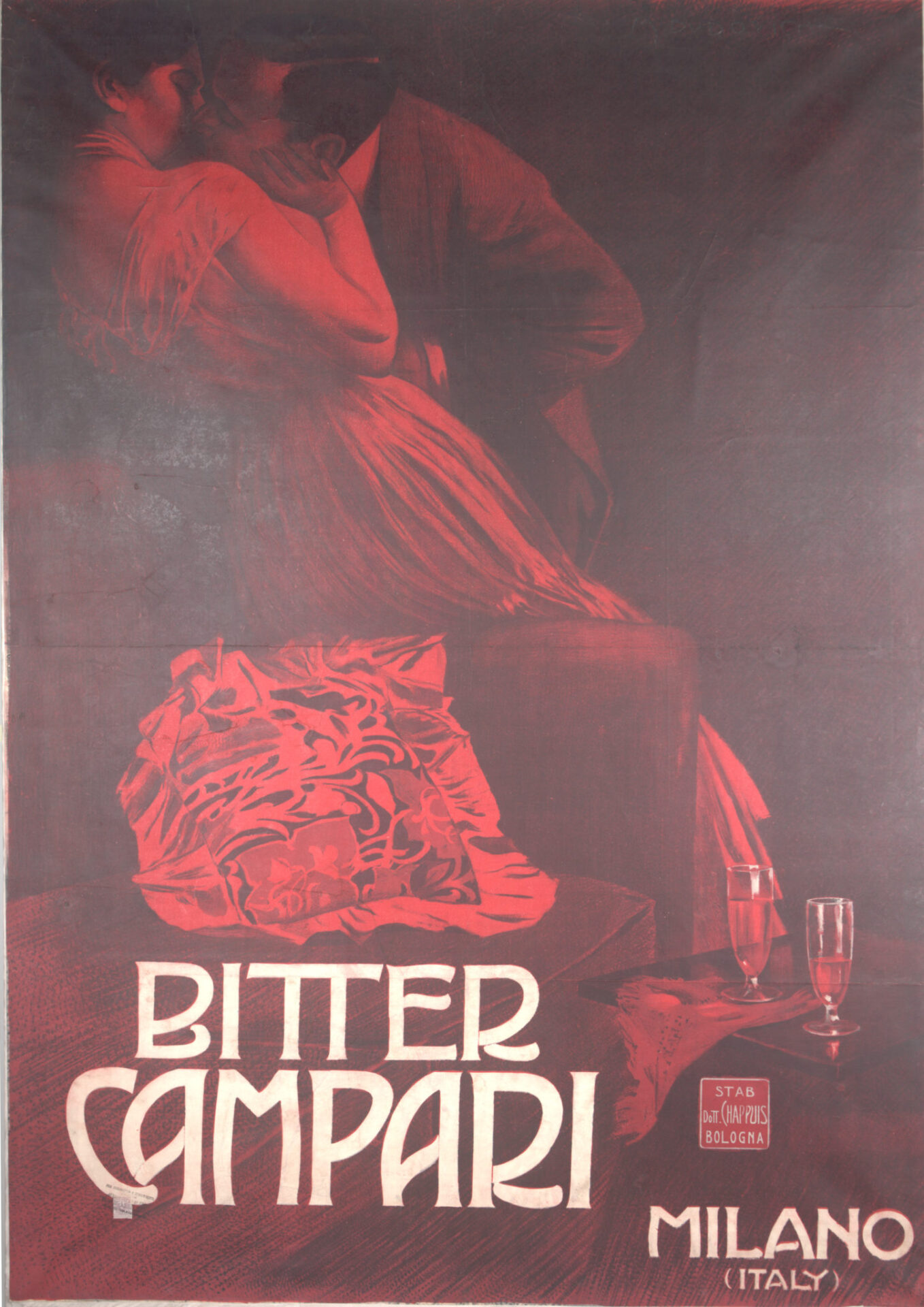

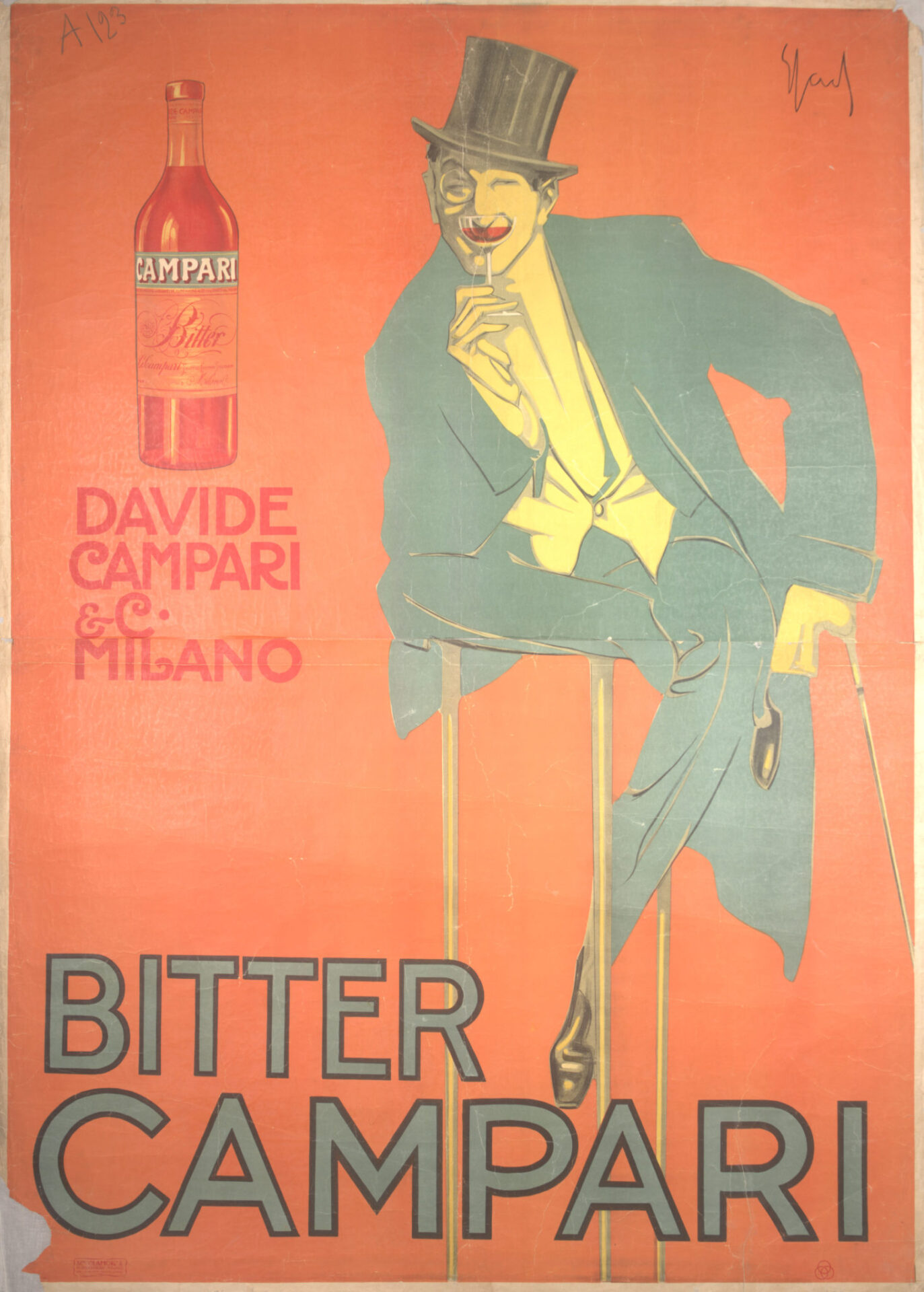

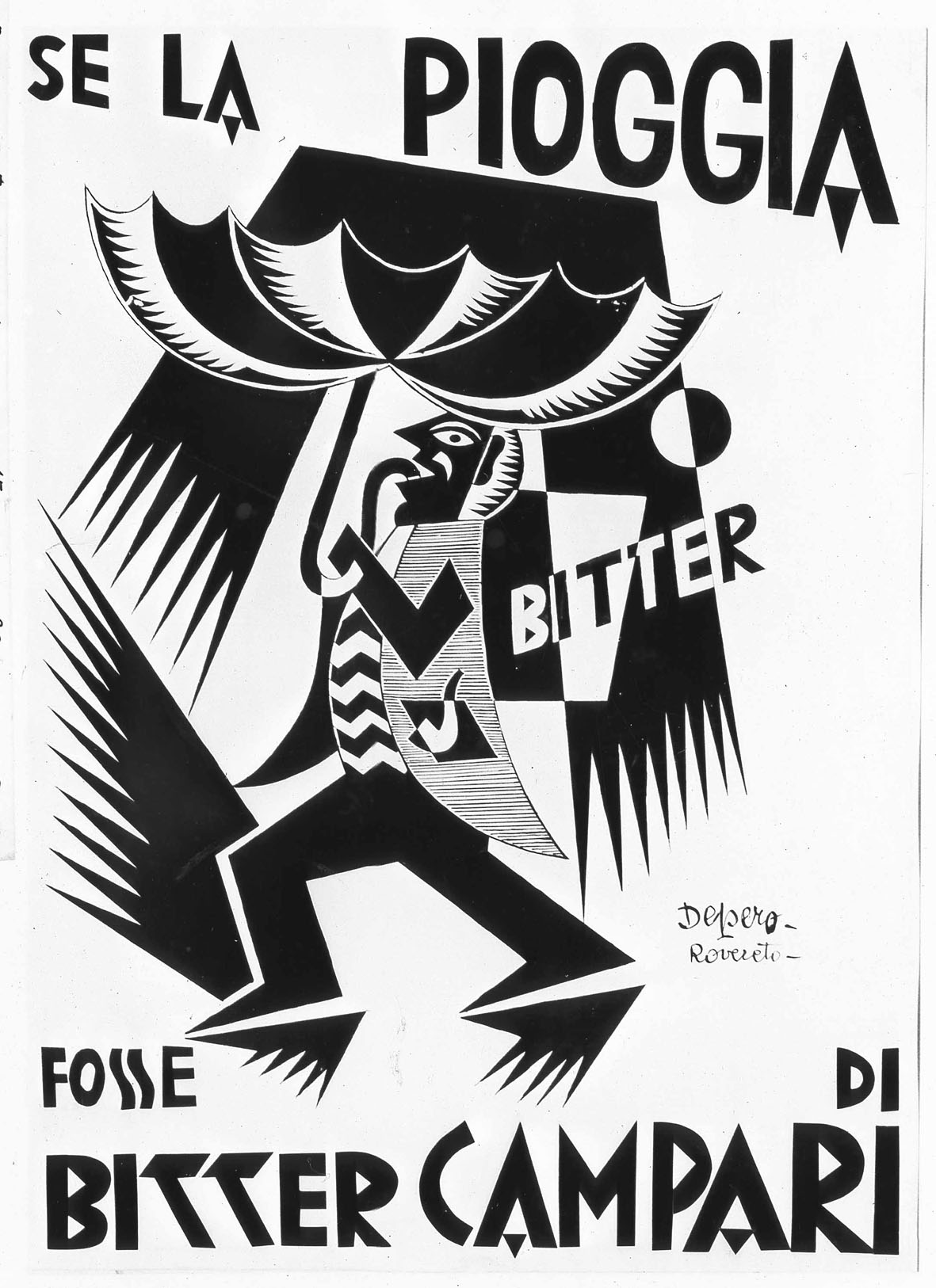

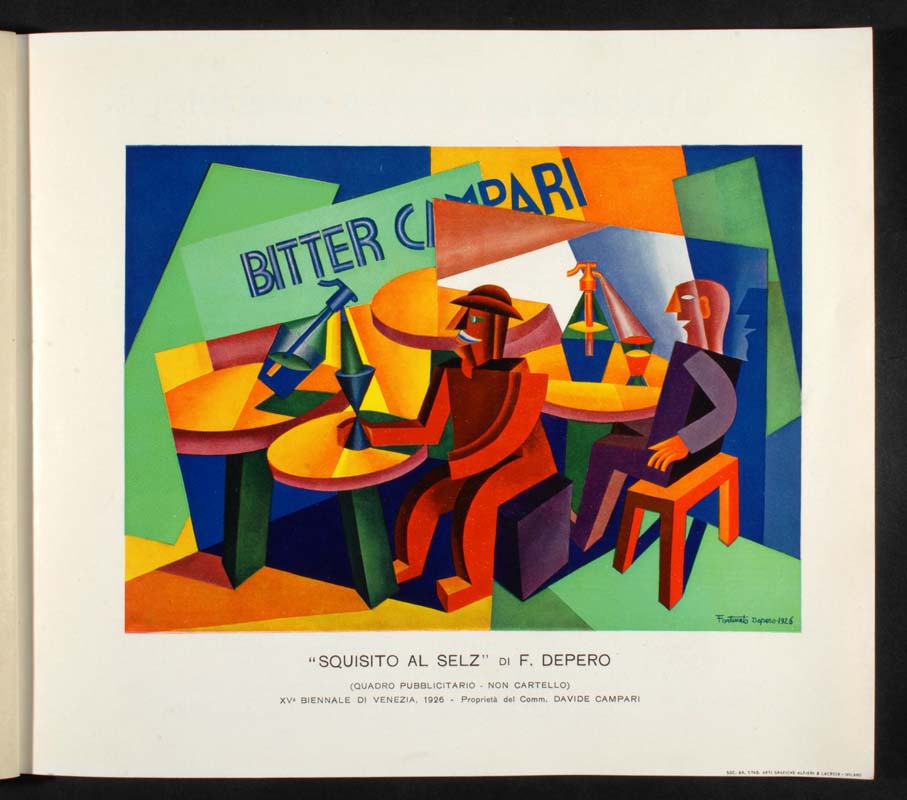

For at least three decades in the early twentieth century, the Milan-based liquor company Campari influenced the language of contemporary graphic design through its posters and graphic identity. Demonstrating an exceptional understanding of the potential of a modern advertising campaign, Campari called on many innovative artists, including Marcello Dudovich (1878–1962; figure 16), Enrico Sacchetti (1877–1967; figure 17), Leonetto Cappiello (1875–1942), Marcello Nizzoli (1887–1969; figure 18), and of course Depero (figure 19). Depero’s graphic style, with its broken lines, strong use of color, and attention to lettering – inspired by the poetic experience of parolibere (words-in-freedom) – dominated Italian advertising production.

While Depero’s work for Campari is documented from 1924–1925, his official agreement with Davide Campari is dated March 1926, and the artist continued to work for the company until 1937. Depero’s remit was extensive, from the design of the Campari Soda Vending Machine signs to the presentation at the XV Venice Biennale, held in 1926, of a quadro pubblicitario – non cartello (painting advertisement – not a poster) called Squisito al Selz (Delicious with Seltzer; figure 20). With this painting, Depero publicly broke down any remaining division between painting and advertising in one of the temples of high art. It was not by chance that in 1931 Depero chose this painting to illustrate the frontispiece of his manifesto, Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria (Futurism and Advertising Art).12

The End of the Decade

Depero and his wife Rosetta moved to New York in 1928 for two years. In this time, Depero treated advertising as a worthwhile artistic pursuit and no longer used the medium solely to promote his other artistic endeavors. Depero saw the new industrial leaders as parallel to the great art patrons of the Renaissance:

Even today we have captains of business who run powerful campaigns in order to publicize their battles, their labors on behalf of their own projects and products – for example, PIRELLI,13 the king of infinite rubber forests, the owner of mountains of rubber, who produces millions of tires that give or increase the world’s speed – isn’t that a poem? a drama? a painting? the awesome architecture of the highest poetry, the most magical palette, the most diabolic fantasy? – ANSALDO – FIAT – MARCHETTI – CAPRONI – ITALA – LANCIA – ISOTTA FRASCHINI – ALFA ROMEO – BIANCHI, etc.,14 aren’t they miracle factories which create and hurl forth mechanical furies – mechanical sirens – mechanical eagles… creating new super delights: the ecstasy of speed and space?15

Pirelli

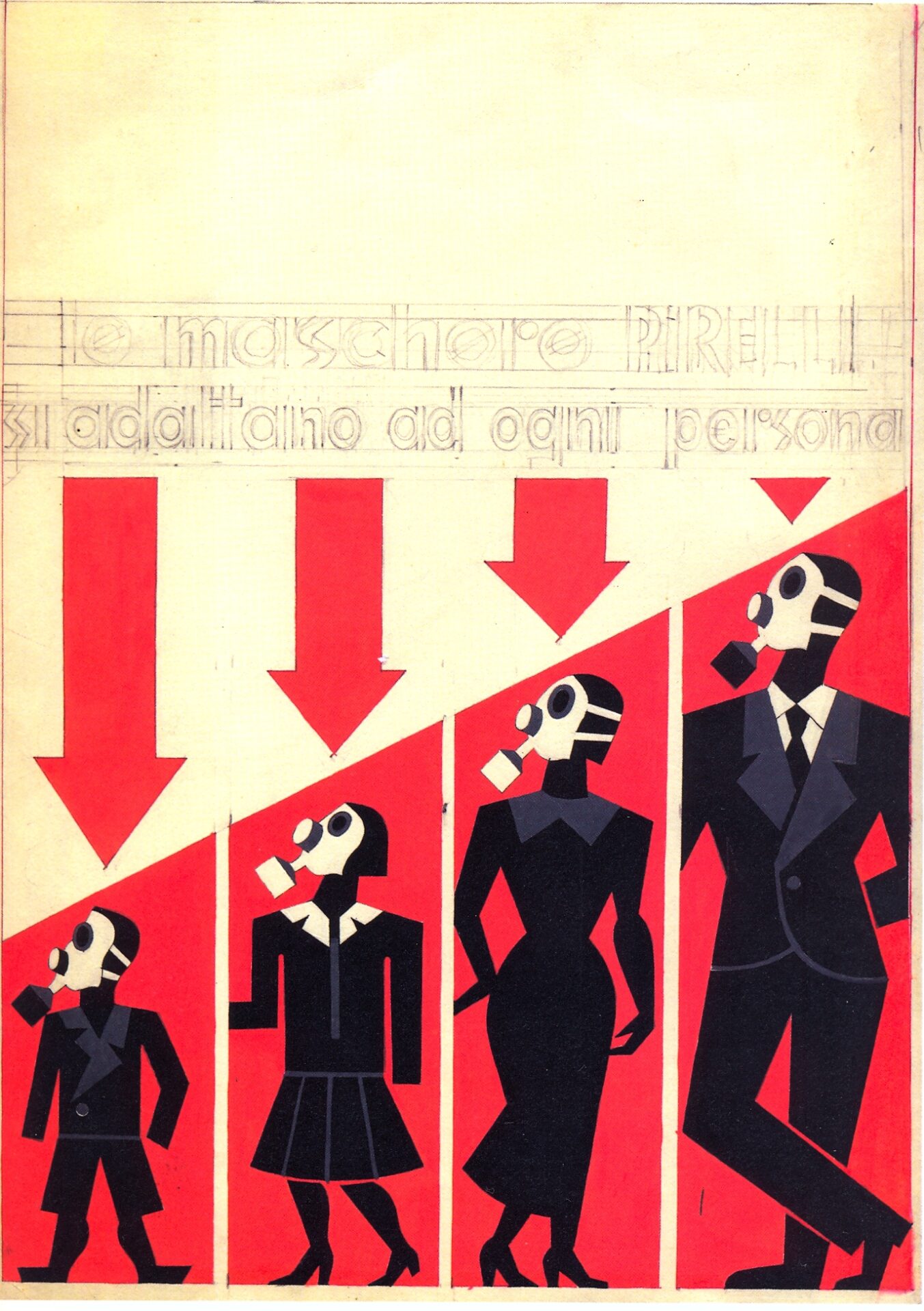

Pirelli was one of the most important Italian and European companies in the 1920s. Depero’s relation to the company, however, was little known until recent research by scholars with access to the archives of both the Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto (from now MART) and the Pirelli Company shed light on that relationship.16 The Pirelli story exemplifies both Depero’s attitude towards potential customers with the Casa d’Arte Futurista and the difficulties he encountered when trying to convince clients to accept his innovative graphic designs.

In late 1927, Azari urged Depero to get in touch with Pirelli to offer them his services in general, and in particular to make decorative designs for the new rubber floors which the company had just put on the market.17 The artist also proposed creating the advertising campaign for Pirelli in the United States. The company thanked Depero for sending a copy of his ‘Bolted Book’ (which the author had presented as a kind of calling card) but declined the offer.18 Between 1938 and 1939 Depero tried again, for the second and last time, to work for Pirelli. He made two advertisement sketches for gas masks, but they do not appear to have been welcomed by Pirelli (figures 21–22).

At the same time, the Bianchi Company – a manufacturer of automobiles, motorcycles, and bicycles – also rejected Depero’s proposals, citing economic reasons. An advertising sign, recently discovered underneath the surface of Depero’s Motociclista, solido in velocità (Biker, Solidified in Speed), was probably part of this abandoned campaign.19

Radio advertising

Another example of Depero’s multifaceted talent in advertising was the publication in 1934 of a book titled Liriche radiofoniche (Radio Poems; figure 23), in which he wrote:

I have defined these lyrics as ‘radiophonic’ because some of them were created specifically for the radio and because the others also contain the necessary elements that radio broadcasting requires.20

In Italy, the Società Italiana Pubblicità Radiofonica Anonima (SIPRA) was established in 1926, while in the US, Procter & Gamble produced and sponsored the first radio soap opera to promote their products in 1930. Thus, even in this specific area Depero was an avant-garde author. His first liriche pubblicitarie (advertising lyrics) date from February 1928. These Futurist poems were short slogans or narratives for products for which the artist had already received poster or other advertising commissions, such as the Bitter and Cordial Campari or Magnesia S. Pellegrino (figure 24). For Pirelli, too, Depero created a number of lyrics in the early 1930s extolling the glories of Pirelli foam.

Architectural advertising

Beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, the temporary architecture of fair stands, shops, and kiosks became fertile terrain for advertising. International industrial exhibitions were housing incredible, monumental plastic constructions, often with roots in classical architecture, in which traditional compositional elements – weapons, musical instruments, hunting and allegorical figures – were replaced by product-related items.

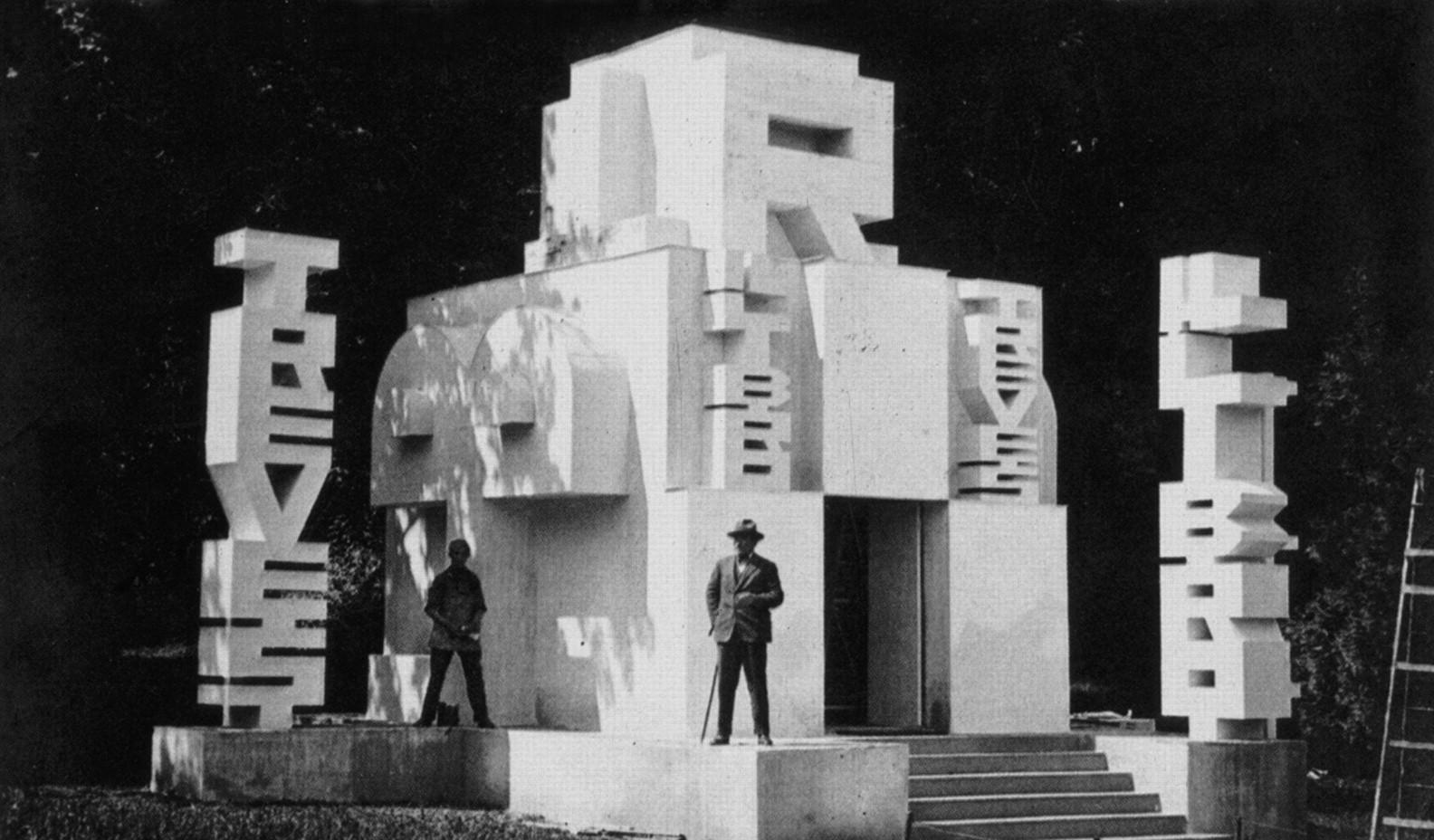

Depero experimented more than once with this particular type of promotion. In his 1927 Padiglione del libro (Book Pavilion; figure 25) at the third Monza Biennale, Depero turned the entire building into an advertisement using what he called “architectural typography” – huge typeface letters forming the words “il libro” and “Treves” were used as architectural elements in and of themselves. Depero felt that exposition architecture for cars, machines, airplanes, and the like designed in a Greek, Roman, Baroque, or Art Nouveau style was ludicrous. He believed that the architecture should instead emerge from the lines, colors, and structure of the objects themselves. Hence his creation of the Bestetti, Tumminelli, and Treves book pavilion inspired by typographic fonts. Later, Depero followed the same approach in a pavilion he designed for Campari in 1933.

Conclusion

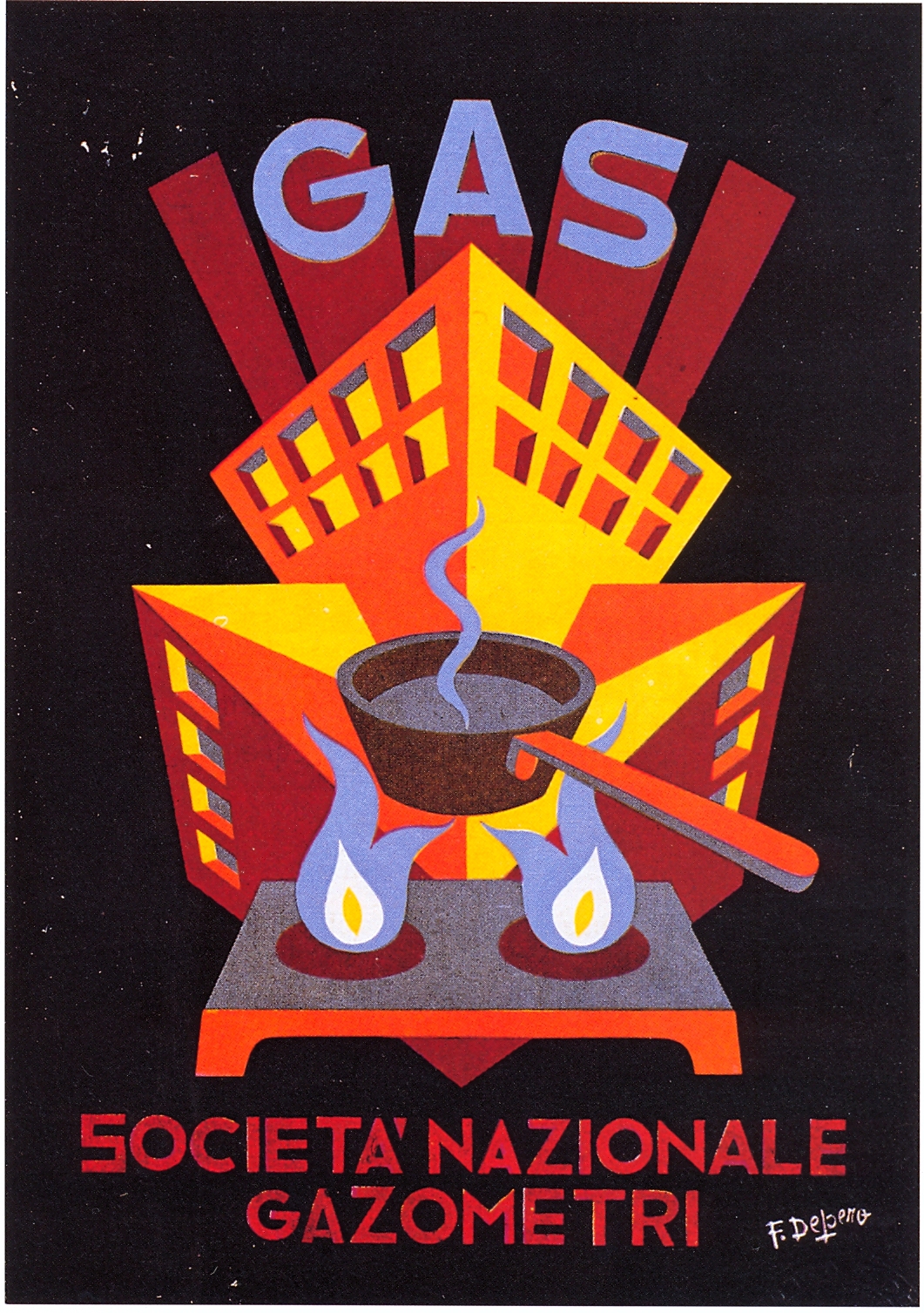

By the late 1930s, the large advertisement commissions that Depero and his Casa d’Arte had been receiving on a national and international level waned, giving way to work from a smaller, local clientele. Recent Depero studies have shown that such circumstances were related to the ritorno all’ordine (Return to Order) – the drastic change in the official art of the regime, and therefore of popular taste, to restored ancient aesthetic values, left little room for the playful inventions of the Rovereto artist. Be that as it may, Depero continued to create some works worthy of mention during this period, such as the posters he designed for the gas distribution company, Società Nazionale Gazometri (figure 26).

In 1936, Guida Ricciardi, the most important handbook for Italian commercial advertising, published a text by Marinetti in which the artist underscored the close link between Futurist art and advertising:

Advertising has only one raison d’être: to engage the curiosity of the public with the greatest originality, greatest synthesis, greatest dynamism, greatest simultaneity, and greatest impact. It must therefore be Futurist. It cannot rely on any traditional means or on any usual form. Those hoping to keep it in an outdated form are damaging a production that has a right to be valued. I consider Futurist advertising designers to be genuine creative artists.21

It was therefore especially the second generation of Futurists, supported by the inexhaustible vitality of its founder, who in their practice made the most of those advertising systems that were assets of the commercial and industrial world, and which had been used from the very first public appearances of the movement: flyers, newspaper ads, billboards, posters and so on, all used to promote the artistic initiatives of the group. With Futurism, these communication systems entered the universe of art, challenging the negative judgment of most of the intellectuals who criticized Marinetti’s style for being too ‘American.’

The pervasive interest of the Fascist regime in the world of images in general made its mark in the advertising field; in 1936, the Sindacato Interprovinciale Fascista di Belle Arti of Lazio organized the Prima Mostra Nazionale del Cartellone e della Grafica Pubblicitaria (First National Exhibition of Billboard and Advertising Graphics) in Rome’s Palazzo delle Esposizioni. In the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Antonio Maraini wrote,

[T]he Union has recognized the singular importance of the billboard and of advertising graphics, which are one and the same thing, for while in any other kind of art it is impossible to identify the client as a category, here you can.22

After this first Roman initiative, in which the artist from Rovereto was not represented, other shows curated by other regional offices of the Union featured Depero’s posters for Campari, Michelin, and other clients, some of which even won awards.

On May 29, 1952, Depero was invited to a conference in Milan on the occasion of the Mostra del Bozzetto Pubblicitario Edito e Inedito (Published and Unpublished Commercial Advertisement Exhibition). In addition to presenting some drawings, Depero gave a talk in which he developed the theme of the application of poetry and art to advertising, starting from his Futurist experiments and claiming the centrality of his 1931 manifesto before moving on to discuss contemporary advertisers. At the same time, diligently granting the request made by the organizers of the conference, he devoted some time to the work of Gino Boccasile (1901–1952), a popular illustrator who had recently passed away, a master of narrative figuration still tied to nineteenth century naturalism, whose taste was therefore in complete contrast to the cutting edge graphic developments inspired by the Futurists (figure 27).

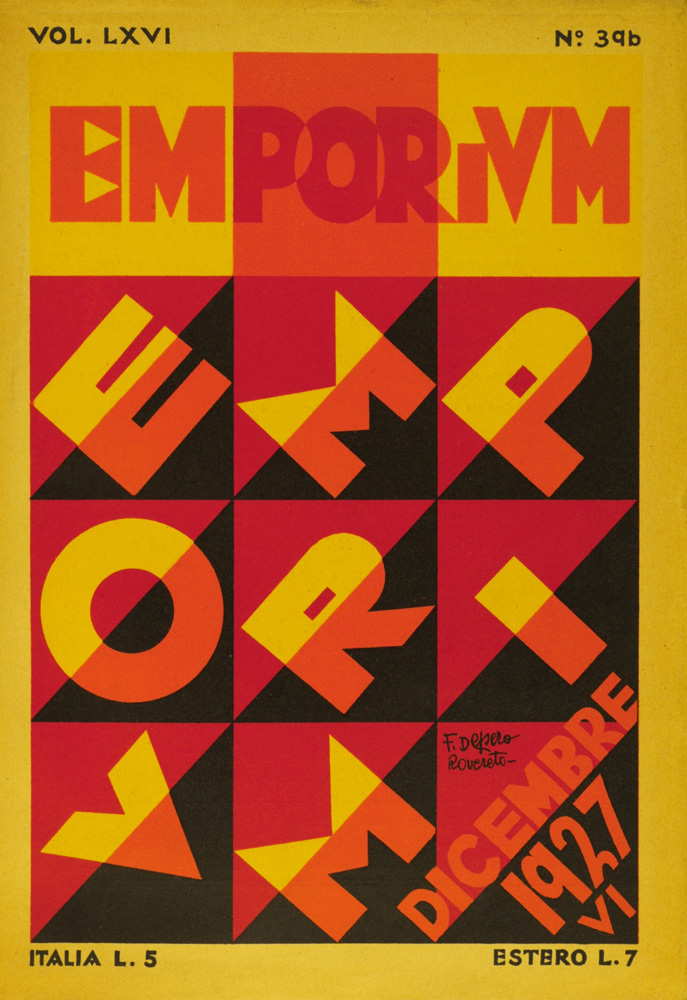

When faced with the complexity of the legacy of Depero’s multifaceted career, one might consider the artist’s enigmatic Nove teste con cappello (Nine Heads with Hat). The small tapestry – which the artist realized before 1932, likely during his stay in New York – follows the structure of the cover he had made for the December 1927 issue of Emporium (figure 28). Seen from a contemporary perspective, the graphic grid of nine repeated elements is of a kind with later work by Andy Warhol, who took part in New York’s same advertising world at the beginning of his own career decades later.

Bibliography

Balla, Giacomo and Fortunato Depero. Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo. Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista (March 11, 1915).

Belli, Gabriella and Beatrice Avanzi, eds. Depero Pubblicitario: dall’auto-réclame all’architettura pubblicitaria. Milan: Skira, 2007. Exhibition catalogue.

Boccioni, Umberto. Pittura Sculture futuriste. Milan: Edizioni Futuriste di “Poesia,” 1914.

Cimorelli, Dario and Giovanna Ginex, eds. Storia della comunicazione dell’industria lombarda, 1881–1945. Cinisello Balsamo: Mediocredito Lombardo, 1997.

Colombo, Fausto. L’industria culturale italiana dal 1900 alla seconda guerra mondiale: Tendenze della produzione e del consume. Milan: Pubblicazioni dell’I.S.U. Università Cattolica, 1997.

Depero, Fortunato. “Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria.” In Numero unico futurista Campari. Milan: Campari, 1931.

Depero, Fortunato. Liriche radiofoniche. Milan: Morreale, 1934.

Ginex, Giovanna. “Not just Campari! Depero and advertising.” In Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, edited by Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, 308–317. Madrid: Fundación Juan March, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Ginex, Giovanna, ed. Una musa tra le ruote: Pirelli: un secolo di arte al servizio del prodotto. Mantova: Corraini, 2015.

Il lavoro nella pittura italiana d’oggi: 70 pittori italiani d’oggi. Collezione Verzocchi. Milan: Verzocchi, 1950.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. “Gli avvisi luminosi: Lettera aperta a S.E. Mussolini.” L’Impero 5, no. 37 (February 12, 1927).

Notari, Umberto. “Depero e la sua casa d’arte.” In Grande esposizione arazzi, cuscini, pittura della Casa d’arte Depero. Rovereto: Casa d’Arte Depero, 1921. Exhibition catalogue.

Prima Mostra Nazionale del Cartellone e della Grafica Pubblicitaria Roma a. XIV. Milan: Pizzi & Pizio, 1936. Exhibition catalogue.

Ricciardi, Giulio Cesare. Guida Ricciardi: pubblicità e propaganda in Italia. Milan: Ricciardi, 1936.

Ripellino, Angelo Maria. L’arte della fuga. Naples: Guida, 1987.

Salaris, Claudia. Il futurismo e la pubblicità: dalla pubblicità dell’arte all’arte della pubblicità. Milan: Lupetti, 1986.

Trisbis (pseud. of Luca Beltrami). “Le colonne luminose nella civiltà moderna,” La Perseveranza (Milan; November 21, 1903).

How to cite

Giovanna Ginex, “Not Just Campari! Depero and Advertising,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/not-just-campari-depero-and-advertising/, accessed [insert date].

- This essay is an extended version of the paper developed for the Fortunato Depero Study Day organized by the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA), in New York on February 21, 2014, and published as Giovanna Ginex, “Not just Campari! Depero and advertising,” in Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, eds. Manuel Fontán del Junco, Llanos Gómez, and Erica Witschey, exh. cat. (Madrid: Fundación Juan March, 2014), 308–317.

- Trisbis, “Le colonne luminose nella civiltà moderna,” La Perseveranza (Milan; November 21, 1903). Trisbis was the pseudonym of Luca Beltrami (1854–1933).

- “Gloria alla grande réclame rossa, rivendicatrice della natura nell’archeologico e trionfante come complementare sul paesaggio verde di rabbia. Gloria alle grandi réclames che si ripetono violentemente espressive a tratti uguali, esasperando gli esteti dell’arcadia…. Le affiches gialle, rosse, verdi, le grandi lettere nere, bianche e blu, le insegne sfacciate e grottesche dei negozi, dei bazar, delle liquidazioni…. ” Umberto Boccioni, “Contro il paesaggio e la vecchia estetica.” In Umberto Boccioni, Pittura Sculture futuriste (Milan: Edizioni Futuriste di “Poesia,” 1914); quoted from Angelo Maria Ripellino, L’arte della fuga (Naples: Guida, 1987), 123.

- “L’aver lacerato e gettato nel cortile un libro, ci fa intuire la réclame fono-moto plastica…” Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero, Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, March 11, 1915). For a full reproduction of this text in English, see del Junco, Gómez, and Witschey, eds., Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, 369–275.

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Gli avvisi luminosi: Lettera aperta a S.E. Mussolini,” L’Impero 5, no. 37 (February 12, 1927).

- “Noi dobbiamo risuscitare l’arte del cartellone. Noi dobbiamo violentemente costringere il pubblico a fermarsi agli angoli delle strade in contemplazione di un avviso murale irresistibile…davanti a un cartellone del giovane artista trentino il passante deve soffermarsi con un grido di sorpresa.” Umberto Notari, “Depero e la sua casa d’arte,” In Grande esposizione arazzi, cuscini, pittura della Casa d’arte Depero (Rovereto: Casa d’Arte Depero, 1921), 18.

- Giuseppe Verzocchi, Il lavoro nella pittura italiana d’oggi: 70 pittori italiani d’oggi. Collezione Verzocchi (Milan: Verzocchi, 1950).

- Fedele Azari to Fortunato Depero (January 9, 1928; MART – Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero).

- SNIA, Società Nazionale Industria Applicazioni, industrial group that began producing synthetic textiles after the war and since 1922 is called SNIA-Viscosa.

- Ferrania, company founded in 1915 devoted to the manufacture of photographic material.

- Fortunato Depero to Gianni Mattioli (December 30, 1930; Mattioli Archive).

- Fortunato Depero, “Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria,” in Numero unico futurista Campari (Milan: Campari, 1931), 19–21, quoted in Claudia Salaris, Il futurismo e la pubblicità: dalla pubblicità dell’arte all’arte della pubblicità (Milan: Lupetti, 1986), 130–131. For a full reproduction of this text in English, see del Junco, Gómez, and Witschey, eds., Futurist Depero: 1913–1950, 422–423.

- The Pirelli company was established in Milan in 1872 by Giovanni Battista Pirelli to manufacture rubber products; however, by World War I it had become a large multinational that also produced insulated cables.

- Ansaldo was a metallurgical company set up in Genoa in 1853. Fiat is a car manufacturing firm founded in Turin in 1899 by a group of investors led by Giovanni Agnelli; in addition to cars, it has manufactured railway engines, military vehicles, farm tractors, and aircraft. Marchetti was an aircraft manufacturer set up by Umberto Savoia in 1915 as SIAI, renamed SIAI-Marchetti in 1943. Caproni was an aircraft manufacturing company established by Giovanni Battista Caproni in Milan in 1908. Itala was a car manufacturing firm founded in Turin in 1903. Lancia is a car manufacturer set up by Vincenzo Lancia in Turin in 1906. Isotta Fraschini is a car and airplane engine manufacturer founded in Milan in 1898. Alfa-Romeo is a car company set up by Alexandre Darracq in Milan in 1906. Bianchi was a bicycle manufacturing firm founded in 1885 which from 1905 began producing cars.

- “Anche oggi abbiamo i nostri capitani che annotano poderose imprese per la valorizzazione delle loro battaglie, delle loro campagne per i propri prodotti e progetti – ad esempio PIRELLI, re di selve infinite di caucciù, proprietario di montagne di gomma, produce milioni di pneumatici per dare ed acrescere la velocità al mondo– non è questo un poema? un dramma? un quadro? una formidabile architettura della più alta poesia, della più magica tavolozza, della più diabolica fantasia? ANSALDO – FIAT – MARCHETTI – CAPRONI – ITALA – LANCIA – ISOTTA FRASCHINI – ALFA ROMEO – BIANCHI ecc. non sono cantieri di miracoli che creano e gettano furie meccaniche – sirene meccaniche – aquile meccaniche… creando la nuova superdelizia: l’estasi della velocità e dello spazio?” Fortunato Depero, “Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria,” quoted in Salaris, Il futurismo e la pubblicità, 130.

- These are the documents I consulted at MART: letter from Nato [Fortunato Depero] to Nina [Rosetta Amadori Depero] (July 15, 1924); letter from Azari to Depero (December 30, 1927); manuscripts and drawings in the folder labeled “Fortunato Depero, Milano, Maggio 1928” (some of them concerning Linoleum); letter on letterhead “Società italiana Pirelli, Milano” to Fortunato De Pero [sic] (June 21, 1928); manuscript, minute of “Addizione d’immagini pubblicitarie, ovverosia….Depero cartellonista” of [Fortunato Depero] (February–March 1928); manuscript and typescript of “Velocità ed elasticità” (1931–1932); manuscript of “Bambole felici” (1934); manuscripts of “Il violinista e il panettone,” “Sedili e giacigli,” “Dinamismo di una signora metropolitana” (1934–1935); manuscript cover, typescript and carbon paper copy “Velocità e felicità” and “Le nuove imbottiture di crine gommato Hailok per la Balilla” (1934–1935); letter on letterhead “Stile futurista. Estetica della macchina. Rivista mensile d’arte-vita” to Fortunato Depero (March 9, 1935).

- Fedele Azari to Fortunato Depero (December 30, 1927; MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero). For a more detailed analysis see Giovanna Ginex, ed., Una musa tra le ruote: Pirelli: un secolo di arte al servizio del prodotto (Mantova: Corraini, 2015.) The book is also available in English as The Muse in the Wheels: Pirelli: a Century of Art at the Service of Its Products.

- Pirelli Company to Fortunato De Pero [sic] (June 21, 1928; MART. Archivio del ‘900, Fondo Depero).

- This find was first described by Gianluca Poldi at the Fortunato Depero Study Day, Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA), New York, February 21, 2014 (now published here).

- “Ho definito queste liriche ‘radiofoniche’ perché alcune di esse furono create espressamente per radio-trasmissioni e perché le altre contengono pure gli elementi necessari che le radio-trasmissioni esigono.” Fortunato Depero, Liriche radiofoniche (Milan: Morreale, 1934), 7–8.

- “La pubblicità ha soltanto una ragione d’essere: quella di agganciare la curiosità del pubblico con la massima originalità, la massima sintesi, il massimo dinamismo, la massima simultaneità e la massima portata mondiale. Deve essere quindi futurista. Non può appoggiarsi a nessun mezzo tradizionale e a nessuna forma consueta. Coloro che sperano di mantenerla in un’atmosfera passatista danneggiano la produzione che ha diritto di essere valorizzata. Considero i pittori pubblicitari futuristi come autentici artisti creatori.” Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, quoted in Giulio Cesare Ricciardi, Guida Ricciardi: pubblicità e propaganda in Italia (Milan: Ricciardi, 1936), 418.

- “Il sindacato ha riconosciuto l’importanza particolare del cartellone e della grafica pubblicitaria che è tutt’uno, in quanto mentre per ogni altra specie d’arte non è possibile individuare come categoria il committente, per essa invece lo si può.” Prima Mostra Nazionale del Cartellone e della Grafica Pubblicitaria Roma a. XIV, exh. cat. (Milan: Pizzi & Pizio, 1936), 15.