Fortunato Depero and Avant-garde Dance

Nell Andrew Nell Andrew Fortunato Depero, Issue 1, January 2019https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/depero/

Was there a Futurist dance? In the context of the wider European Avant-garde’s involvement with dance, this paper presents two projects of the Italian Futurist Fortunato Depero: the Ballets Russes’ Le Chant du Rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale; 1916–1917) and the automaton ballet I balli plastici (Plastic Ballets; 1918). Through his designs, Depero aligned with and contributed to the vanguard dance theories of his time.

Was There a Futurist Dance?

Amidst other movements of the historical Avant-garde, Futurism’s legacy was established in great measure by its acts of performance involving the live, physical engagement of an audience. But what does the term ‘dance’ mean when used in reference to a distinct component or idea within Futurist performance? Futurist theory is known to concentrate on speed and movement. There even exist written references to the potential uses of dance, awareness of contemporary dancers, and a stand-alone manifesto on the topic (published in 1917). Yet, Patrizia Veroli is quite right in her skepticism that there ever existed such a thing we might accurately call Futurist dance.1

Although Futurists in various disciplines initiated radical assaults on the traditions of painting, music, and theater, the movement lacked committed affiliation with trained dancers or theorists who would have understood dance traditions and their potential for ‘futurizing.’ Nevertheless, the model of dance provided the movement with a potent example of synthetic art. There is repeated evidence that the group considered and attempted to make use of dance in Futurist production both before and after the war. Futurism’s forays into the choreography of bodies on stage have been approached most successfully – by scholars such as Günter Berghaus and RoseLee Goldberg – from the perspective of theatrical innovation.2 Indeed, one aspect of dance is its live, theatrical nature, but more often than not, performance is neither the medium’s creative impetus nor its fulfillment. If we consider dance only through the terms of theater and performance, we lose the possibility of locating medium-specific qualities of dance as an autonomous medium of art. It is in the plastic work of Fortunato Depero that we find a Futurist most closely identifying with dance. This essay will present a wider European context for the plastic arts’ involvement with dance so as to highlight how Depero’s plastic and conceptual engagement with dance distills core Futurist anxieties and imagined solutions regarding the human body and its synthesis in art.

Two projects by Depero in particular show an alignment with, and contribution to, the vanguard dance theories of his time. In 1916, the artist received a commission from Serge Diaghilev, director of the illustrious Ballets Russes in Paris, to build a stage set and costumes for the ballet, Le Chant du Rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale). It was a major undertaking for a world-class dance troupe. Although the collaboration would fail, leaving Depero’s designs to languish in his studio, the artist’s detailed plans show an imagined Futurist environment for dance and its actors, one that was ultimately incompatible with the aesthetic vision of Paris’ most renowned Avant-garde dance troupe. Perhaps more tellingly, Depero succeeded during the following year in bringing dance designs to the stage. He only did so, however, through a mechanical solution – I balli plastici (Plastic Ballets) – his 1918 automaton ballet without bodies.

Dance and the Futurist Avant-garde

At the time of Depero’s Ballets Russes commission, the dance company had already begun to forge a relationship with the Futurists. While Europe headed to war, Diaghilev took his troupe on the road, staging performances in Great Britain, Spain, Switzerland, the Americas, and Italy, where Diaghilev and Stravinsky were energetically hosted in Milan and Rome by Marinetti and his colleagues. The Ballets Russes had been built upon the nineteenth-century ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (Total Work of Art) and aimed to combine dance with equally innovative drama, music, and design. Having arrived in Paris from St. Petersburg in 1909, the company had been staging innovative ballet choreography in collaboration with contemporary painters and composers for several years. Because of their Russian origins, the highly modern innovations in music, design, and choreography were welcomed as part of their generally exotic appeal. Diaghilev, however, sought to imbue ballet performance with increasingly astonishing and anti-naturalist aesthetics, and, throughout many of the seasons leading up to the Depero commission, the troupe’s innovations were compared by the Parisian press to Cubist and Futurist styles. In the years 1912 and 1913, the Ballets Russes were transformed by their lead dancer-choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky’s radical ballets, Afternoon of a Faun and The Rite of Spring (figures 1–2). Nijinsky’s choreography reversed the forms of traditional Russian ballet by geometricizing the dancer’s form and gait: Ballet’s pointed toes, soft fondues, and elongated arabesques gave way, as Nijinsky’s dancers flexed, jabbed, shuffled, and leapt in abrupt and planar gestures. Nijinsky’s ballets juxtaposed and interwove mechanical movements with raw, primitivist naturalism. In this vein, there is an obvious correspondence with the experimentations of Futurist and Cubist painters who, in the early twentieth century, likewise vied to communicate the ambivalent new materials, spaces, and psychologies of the modern industrial world.3

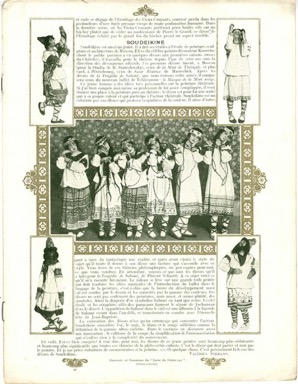

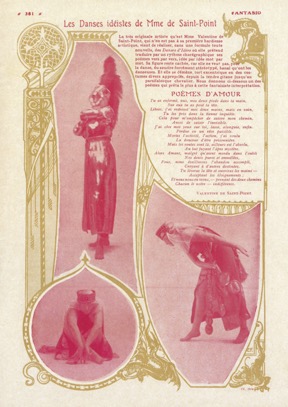

Beyond the choreographers of the more popular Ballets Russes, French and Italian Avant-gardists would have also been aware of a more elusive theory of creating Total Works of Art through dance from the work of Valentine de Saint-Point, one of the few women associated with the early Futurist movement. In the same year of Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring premiere, Saint-Point published a manifesto in the Paris daily newspaper, Le Figaro, outlining her theory of dance called La Métachorie (or Metachorus). Enlisting this theory, Saint-Point aimed to create an Ideist dance that synthesized dance’s sensual, bodily movement with the more cerebral, abstract, and, in her eyes, modern qualities she admired in the music, poetry, and painting of her time.4 The dancer-choreographer premiered this dance in December 1913 at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées, a venue whose larger auditorium saw the premier of Nijinsky’s Rite only months before. Performing a solo in four sections, she moved through a series of sharp, angular poses mixed with softer, more fluid movements (figure 3). As she executed this choreography, Saint-Pont was accompanied by the sounds of an actor offstage reciting her twelve poems, as well as a live orchestra playing music by contemporary composers that she had selected herself. Meanwhile, incense wafted into the air from copper urns dispersed around the room, and on a simple drop cloth hung behind her, electric lights projected a changing sequence of abstract drawings – the ‘idea figures’ of her dance.

Métachorie aimed to move dance beyond illustrative gestures and purely visual reception. Saint-Point’s use of unfamiliar sounds and smells activated an outward expansion of the dancer’s form into the surrounding space, uniting the performer and her stage with the audience, both physically and metaphorically, into a synthetic Total Work of Art.5 Because of her correspondence and collaborations with Marinetti, including her publication of two Futurist manifestos – the 1912 Manifesto of the Futurist Woman and 1913 Futurist Manifesto of Lust – the Futurist directory in Milan soon included the poetess Saint-Point under the title “azione femminile” (female action). However, Marinetti’s hope to forge a Futurist element in Saint-Point’s dance by connecting her with the Futurist composer F. Balilla Pratella did not pan out.6 In fact, in the years following her manifestos, Saint-Point denied any official association with the movement, and by 1917 Marinetti would disparage La Métachorie as overly nostalgic and static in his Manifesto of Futurist Dance.7 Nevertheless, Saint-Point’s synthetic, multi-media performance received attention in both the popular and Avant-garde press, thereby introducing a link between dance and Futurist ideas to a wide range of Avant-garde artists, writers, and filmmakers. Saint-Point’s theory of dance as a Metachorus, moreover, promoted what was then becoming a prevailing idea of dance as the most synthetic form through which to unite the arts.

As early as 1914, Diaghilev met with Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, and Giacomo Balla to express his interest in a possible Futurist collaboration.8 Following the Ballets Russes’s U.S. tour in 1916, Diaghilev rented a flat in Rome with his new favorite choreographer, Léonide Massine, and gathered around him his collaborators from Paris, Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso. As the group began working on what would become the Parade, Diaghilev approached Depero and Balla to produce décor for the company’s spring season. To Depero, he assigned the set and costumes for an upcoming ballet The Song of the Nightingale, an adaptation of a full-length opera for which Stravinsky was still completing revisions.9 Weeks later, he commissioned Balla to produce designs to accompany a musical interlude of Stravinsky’s Fireworks. It was at that time early December, and both designs were to be ready for an April premiere in Rome. Diaghilev had perhaps read the pair’s 1915 manifesto, Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo (Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe), which proposed a new dynamism of experience through abstract plastic ensembles that perform rotations of irregular speeds and transform variably by smell, noise, appearances, and departures.10 The impresario would have imagined a Futurist-built universe for his own stage, fitted with sensory apparitions, kinetic dynamism, explosions, and fireworks. But in the end, he took only the last of these attributes from the Futurist pair.

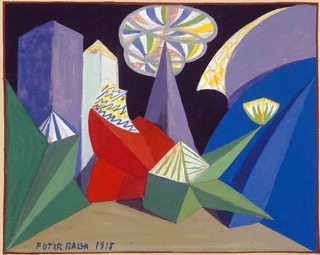

Balla’s Fireworks design preceded its commission. The artist had been working on “the first plastic complex,” since 1915, when it was described in his and Depero’s manifesto as “an abstract landscape of cones, pyramids, polyhedrons, spirals of mountains, rivers, lights, shadows” (figure 4).11 Balla’s overture of light and color went off without delay during a program of other Ballets Russes works at Rome’s Teatro Costanzi in April 1917. However, a full-length ballet for an immense brigade of human dancers is another thing altogether, and in Depero’s case, his Futurist ballet did not manifest as projected. Despite having seen Depero’s designs and expressing his positive impressions to Stravinsky, Diaghilev would not stage The Song of the Nightingale until 1920, and by then its designs had been given over to the patriarch of French painting, Henri Matisse.12 Scholars have been left to speculate on Diaghilev’s reasons for abandoning Depero’s designs in 1917. Günter Berghaus, Patrizia Veroli, Lynn Garafola, and Juliet Bellow have each studied the collaboration in depth.13 Suggestions include that while Fireworks was merely a design production, putting on a full ballet in a matter of months would have posed many more financial constraints. It is also possible that Stravinsky was struggling to revise his score in the time provided, or that Depero’s designs were coming along too slowly. Then again, after successfully associating his troupe with the Futurists through Fireworks, perhaps Diaghilev – who was wary of Futurism’s overt political ambitions – may have been satisfied to leave their relationship at that.

When confronting the mystery of this unfinished collaboration, it is equally telling to consider what took place between Depero’s commission and the ballet’s eventual staging with sets by Matisse in 1920. The Song of the Nightingale’s plot follows Hans Christian Anderson’s tale of the same name. An emperor keeps a beautiful nightingale in captivity so that she will sing to him, but when he is given a mechanical nightingale as a gift, he and the court become fascinated by the automaton. Forgotten, the captive nightingale returns to the forest. Eventually, the mechanical bird malfunctions, and the Emperor becomes ill. For his health to be restored, the real nightingale must return from the forest and heal him with her song.

As Bellow has pointed out, the opera’s original designs by Alexandre Benois were in line with the orientalist sumptuousness for which the Ballets Russes had become known. Benois set the opera in a lavish palace of blue and gold, draped in textiles, tiled walls, and flickering lanterns (figure 5). Stravinsky’s original 1914 score, moreover, used an orientalist scale that would have sounded exotic to its European audience.14 Yet, the composer’s signature staccato beats, uneven tempos, and dissonant tones additionally marked it as modern. Futurist Luigi Russolo’s intonarumori (musical noise machines) had been introduced that year, and Bellow notes that in The Song of the Nightingale’s first staging, one critic perceived in Stravinsky’s music, “noises… strangely reminiscent of Signor Ruffalo’s [sic] Futurist orchestra of ‘roarers’ and squealers.”15 The ballet’s seemingly modern sound, along with its storyline about a mechanical bird, would have made a Futurist designer a fitting choice for the 1917 reprisal.

In Depero’s imagination, the setting for The Song of the Nightingale shifted from an Orientalizing, Symbolist atmosphere to a Futurist garden with spiky flowers, as well as sharp leaf fronds and clusters of discs, cones, and polyhedrons. While the sets of ballets were typically constructed from such materials as tempera paint and textiles, the artist opted to design his own landscape in wood, cardboard, and iron; he then coated his scenery, startlingly, in bright enamel and varnish (figure 6).

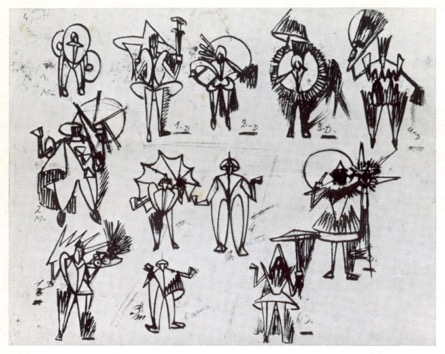

Depero’s plans for the costumes remain only as drawings, but, according to the artist’s descriptions, they would have been

solid in style, mechanical in movement; grotesque enlargements of arms and large, flat legs; hands made of cans or discs or fans with long, pointed and rattling fingers; … bell-shaped coats and trousers and shirt-sleeves; all of them polyhedral and asymmetric, all of them unscrewable and mobile.16 (figure 7)

Following Futurist ideals of a synthetic theater, Depero wished to erase all individuality from performers by swallowing the human figure into his costume shells. In doing so, he would compel the audience to only pay attention to the movement of volumes in space. Though never realized, these human costumes, and their solid, mechanical, modular designs, anticipated Depero’s more celebrated stage design: the marionette theater that he would conceive during the following year for his plastic ballets. Significantly, they also prefigure the Ballets Russes show staged that spring, Parade. Picasso and Cocteau had developed their ideas for this ballet among the Futurists in Rome. Combined with its score by Erik Satie, the production demonstrates the influence of this group of artists in spades.17 Indeed, it can rightfully be deemed the most Futurist staging that Diaghilev ever produced.

Parade: the other Futurist ballet

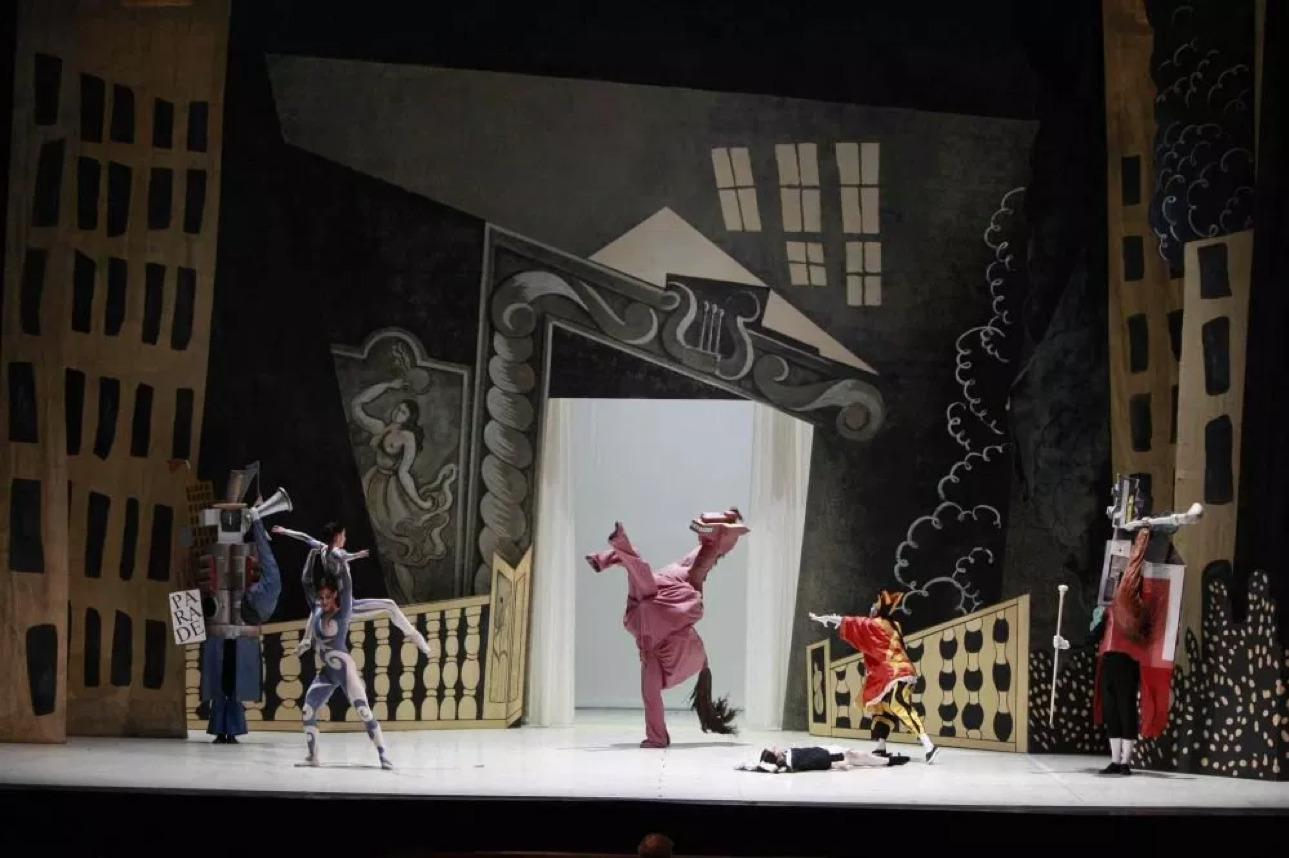

Not least among the Futurist elements of the 1917 Parade is its metaphoric breach of the theatrical fourth wall: the ballet’s plot involves a group of performers who solicit the audience to see their show. The entire performance takes place outside the door to the performers’ tent, where they mime their talents directly toward the spectator – a Futurist allegory of art as provocation (figure 8). Picasso’s costumes for the production reflect Futurist theater’s call for the synthesis of performer and setting. Each costume – from the acrobat’s human-like bodysuits, to the magician’s stiff, painted outfit, to the built prostheses of the manager costumes – transforms the dancers on stage (figures 9–11). They collectively function to move the human body farther from its natural form and merge it with the elements of the stage décor behind them. Comprised of miscellaneous noises, including sirens, bells, and clicking typewriters, Satie’s syncopated score similarly demonstrates an unmistakable indebtedness to Futurist rumorism.

The musical accompaniment along with the varying levels of prosthetic bodies moving on stage gave rise to a contagion of mechanization among the performers. It had been Picasso’s idea to buffoonize the three managers, encasing them in Cubist sculptures that mimicked stuffy French evening wear, New York skyscrapers, and a clumsy horse. These constructions, in themselves, merged the performers with their set, thus dehumanizing them. However, their juxtaposition with life-sized dance partners took the illusion farther. Beside the towering and teetering managers, the balletic Acrobats, and the Little American Girl appear miniature, and yet the living movements of the human dancers call attention to the unnatural mechanics of Picasso’s Cubist bodies.18

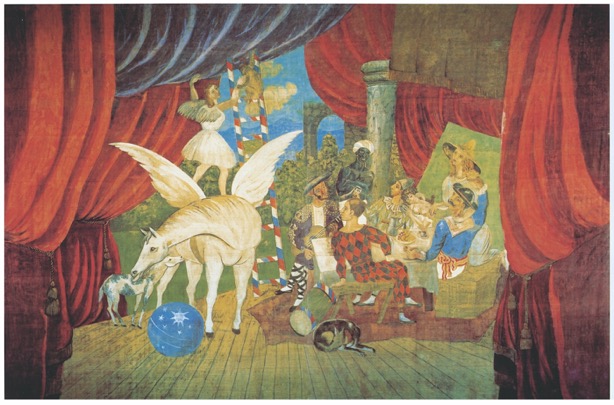

Was Diaghilev’s former fascination with Balla and Depero’s Futurist reconstruction of the universe brought to fruition in Parade? Not entirely. Throughout the ballet, there are concessions to mainstream ballet-goers. Picasso’s drop curtain that preceded the performance served as an homage to the genre of Commedia dell’arte (figure 12); the American Girl was included in the production to recall the stars of Hollywood silent cinema; and the Acrobats in their pas-de-deux offered the audience a more traditional display of virtuosic balletic movement. When Diaghilev returned to the project he had started with Depero, Stravinsky’s The Song the Nightingale, it was 1919; the war had ended, and morale was beginning to be reconstructed. Diaghilev pursued Henri Matisse to redesign the décor for the ballet. Perhaps Parade, whose reception had been mixed, was a lesson. Despite being staged as a benefit for those wounded in the war, Parade had struck chords of xenophobia among audiences, as well as the press. For French viewers, the Russian company risked association with the Bolsheviks, who, in February, had overthrown the Tsarist government in Diaghilev’s hometown of St. Petersburg, putting Russia’s treaty with the Allies at risk. Compounding this agitation was the involvement of Picasso, another foreigner and non-combatant artist whose Cubist style had been disparaged as Germanic for its Anti-naturalism and German-named patrons.19 Matisse on the other hand, was a cultural war hero. Because he had been unfit for military service, he threw himself into painting for the glory of French nationalism. At war’s end, he had left Paris for Nice where he returned to nostalgic imagery of Mediterranean sunlight and sumptuousness. In letters, Matisse indicated that while working on The Song of the Nightingale set, he was pressured by Diaghilev to fill the stage with gold and opulence.20 Although Matisse’s final set is more pared down, he created the same kind of orientalist palace imagined by Benois, with curtained walls and a central gilded throne (figure 13).

Although it is unfair to compare Depero’s unfinished project with the work of Matisse, the two designs could not be more opposed. Had Depero been allowed to complete his Futurist Nightingale, his modular wood and board costumes and cluttered mechanical set would have left little space for the dancers to stand out from the totality of the sensorial experience. In William Butler Yeats famous words, we would not have been able to tell “the dancer from the dance,” nor from anything at all.21 The theme of The Song of the Nightingale, might have been apropos for Diaghilev’s short-lived liaison with the Futurists: the ballet, as mentioned, is a story of fascination with a new, modern mechanical attraction. Its allure, however, is only temporary, and the voice of naturalism returns to finish the ballet.

Why Dance?

Let us return to 1917. Shortly after Parade’s premiere, Marinetti wrote his manifesto on Futurist dance (figure 14).

The essay includes accolades for an eclectic mix of contemporary performances ranging from Picasso’s dance of geometricized volumes, to Loïe Fuller’s electric stages, to the mechanical movements of African American cakewalk dancers. Throughout the text, Marinetti calls for a fusion of man with machine and for a dance instigated not by muscle, but by the multiplied body of a motor. Finally, he insists that music be replaced by organized noise.22 Marinetti’s language and ideas conform to other Futurist writings regarding theater, but his vision for dance stops short. In his three proposed ballets, Marinetti instructs dancers to describe their subjects gesturally and to imitate the movements of various Futurist archetypes: shrapnel, a machine-gun, the aviator. He also claims they should carry printed signs, like intertitles in a film. Marinetti’s directives lead to a dance of mime, metaphor, and narrative, rather than total synthesis.23 Yet, writers like Marinetti, as well as plastic artists from various movements across the European Avant-garde, looked to dance as a model for expanding the expressive capabilities of their own mediums. By unifying art’s materials with its maker, dance may be seen to communicate directly, as if unmediated. In this way, it achieves the modernist ideal of synthesizing form and content.

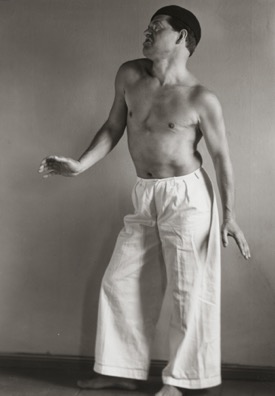

Much of what became Modern dance in the twentieth century was bolstered by the Nietzschean idea that dance could, on the one hand, unify humankind’s Apollonian and Dionysian impulses and, on the other, serve as a bridge between external form and more universal truths. The human art-machine dancers of Depero’s plastic imagination were not only found in Parade but in Avant-garde choreography and design across Europe in the early twentieth century. During the 1910s and 1920s, for instance, Dada artists – like their Futurist counterparts – viewed performance as the primary means to meet their politically radical ends; they deployed bodily humor, grotesque miming, and expressive gesture as forms of resistance to bourgeois propriety amid the ongoing carnage of World War I (figures 15–16). Among Zurich’s earliest Dada artists and performers was Sophie Taeuber who had trained as a dancer under two of Modern dance’s founders, Rudolf Laban and Mary Wigman. The connection between dance and Dada deepened when, in 1917, Laban opened a school in Zurich to teach what was becoming known as the New German Dance. Rooted in Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s school of music, which trained students in rhythmic gymnastics, this genre focused on using movement to externalize intuitive sensations. We might initially associate this sort of expressionism with spiritual aims, and therefore deem it antithetical to Futurism. However, the teachings of Laban and Wigman parallel many Futurist ideas on theater. The expressionism they encouraged in dance focused on abstract or absolute expression, that is, the replacement of individual bodies and their significance with a unifying idea of pure movement. Much like innovators in Futurist theater, Laban and Wigman additionally used masks and bare sounds rather than music. Furthermore, the tempo of their dances swayed from rapid to languid, while their dancers moving shifted sporadically from leaping to crouching earthbound, invoking Dionysian associations of the ecstatic and grotesque (figure 17).

The Dada redirection of Laban and Wigman’s Modern dance is documented in an anonymous photograph of Taeuber dancing in Zurich (figure 18).

In this image, Taeuber appears in a mask and full-body costume: her arms are encased in long rigid tubes that extend from her shoulder to her fingertips; black fabric hides her lower legs and shoulders so that her mask, torso, and limbs seem to float separately, as if strung in space like a marionette. In 1918 – the same year that Depero presented his marionette ballets – Taeuber herself would design and build a cast of marionettes for a psychoanalytic production of Carlo Gozzi’s King Stag (figure 19).24

These examples demonstrate how the masked dances of Dada and Expressionism in the 1910s mirror the Futurist drive to reify and make more palpable the physical form of the human body, while also undermining its specificity and individuality. Choreographers in the interwar period need not have looked far for images of the industrialized, commodified body. Picasso’s sketches for Parade, for example, include numerous references to advertising kiosks and human billboards of sandwich men. Furthermore, for those who had witnessed the alien appearance of gas-masked troops (necessitated by the Futurist weapons of total war), mechanized automatons were not so divorced from reality. The face and body masks used in Avant-garde dance transformed dancers into dolls, automata, and puppets, so that they became parodies, empty doubles of the human form. In this transformation from human to puppet, the hollow body carries metaphysical, allegorical, and political significance.

The Plastic Ballets, 1918

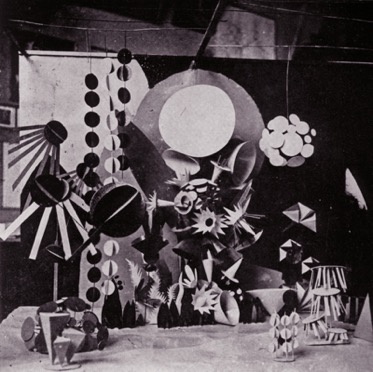

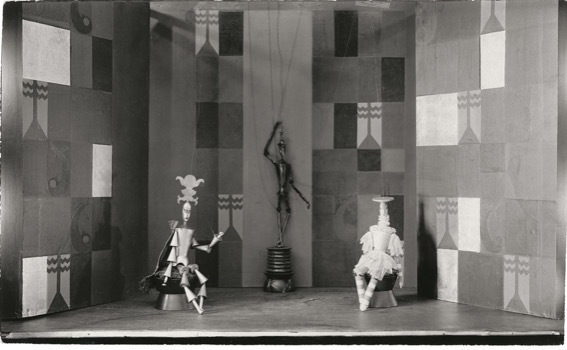

While collaborating on a new idea for a ‘Plastic Theater,’ Depero and the Swiss Egyptologist and writer Gilbert Clavel discovered a solution for Futurist dance only after trading in the human body for the figure of the automaton. The Balli plastici were mounted in May 1918 at Il Teatro dei Piccoli in five performances: Pagliacci (Clowns), L’uomo dai baffi (The Mustachioed Man), L’orso azzurro (The Blue Bear), I selvaggi (The Savages), and an unnamed dance of shadows and lights. The project involved a fleet of wood and wire marionettes constructed by Depero that were propelled into motion on an abstract stage set (figure 20). Reconstructions of the automatons and their environment have been aided by a painting Depero made during the project, which portrays the various marionette characters included in the program (figure 21): white clown figures march across the center; mustachioed men descend an accordion staircase to the right; and across the horizon, the Savages appear in groups of three, four, and five. The painting’s left side displays an artificial landscape that recalls the life-sized sets made for the Ballets Russes. Depero’s synchronization of diverse materials, moving sets, and rotating, entering and exiting actors, aimed for the ideal Futurist performance. Avoiding the idiosyncratic inner content that the presence of a human dancer adds, his puppets made pure gestures without sentiment. As Clavel later wrote, there was “No more distinction between action and representation, between content and form, between character and setting.”25

More generally, by associating plastic arts with the medium of dance, Depero exacerbates the fusion of action and representation. Relying on abstract, yet intentioned movements, dance, after all, unhinges gesture from mimicry and normative bodily movement and awakens the awareness of new, unnamed motor intentions. As kinetic humanoid forms, Depero’s marionettes solicit our kinesthetic empathy, drawing attention to our own motionless and socially conditioned bodies. The uncanniness incited by these puppets, however, also suggests the possibility of new responses, the creation of novel actions and gestures freed from received, quotidian habits. As in other venues of vanguard performance, where dance helped make sense of the natural and artificial ties between the biological body and the modern world, Depero’s marionettes perform an easy slippage from the primitivist slapstick implied by clowns and savages to the jazzy, variety-show aspect of the men with moustaches. In the figure of the Great Savage specifically, Depero created his largest marionette: a belly that opened up to display a miniature stage, on which a second performance was occurring. Through puppets, Depero could again control higher dimensions, moving from the planes of the stage and actors to an internal plane of yet more mechanical actors – in which the inner motor of his largest puppet is revealed to be a mise-en-abyme, simply encompassing more versions of itself. The multiplied dynamic motion creates a concordance between the savage human motor and its mechanical twin.

While Depero’s masked designs for the earlier Ballets Russes dancers may have mirrored ongoing experiments in concert dance across Europe, the plastic theater reform of Depero’s Balli plastici seems to have been ahead of its time. When he introduced his automaton ballet in 1918, Depero was doubtlessly tapped into the vanguard idea of dance as a solution to modern aesthetic concerns. As Europe ‘returned to order’ following the Great War, industrial production and urban centers grew, and dance became an outlet for expressing the human body’s growing dependence on speed, technology, efficiency, perhaps most popularly exemplified by the assembly-line precision of unison dancing troupes like the Tiller Girls. In the interwar years, the Avant-garde treatment of dance and its affinity for the technological would be undertaken by artists in Paris like Fernand Léger, who conceived the film Ballet Mécanique in 1924. Before this project, Léger had already collaborated directly with the stage when he designed La Création du monde for the Ballets Suédois in 1923. Despite presenting a scenario and design with overt primitivist associations, the performance was entirely mechanical. Wearing Léger’s stiff costumes, dancers moved throughout the stage’s tight space, hardly differentiated from the décor. Similarly, artists of the Russian Avant-garde experimenting with Constructivist theater design created sculptural sets that incorporated their actors as cogs in a larger visual machine. In Dessau, Germany, Oskar Schlemmer likewise brought the hybrid dance of organic, plastic, and mechanical parts to life under in the Bauhaus theater workshop. Publishing his theory in a 1924 essay titled Man and Art Figure, Schlemmer wrote of the stage as a site for the synthesis of man and art. Schlemmer’s 1922 premiere of the Triadic Ballet, involved a dozen dancers in sculptural costumes, made variously from metallic wire, paper and board, or soft, stuffed fabrics (figure 22). Each figure was designed to investigate the body as an articulated motor in space.26

In Depero’s hands, dance was dissolved into a plastic art, and his own plastic art was made to dance. Gabrielle Brandstetter has argued that because we think in language, dance can render us speechless. In dance, we are made to perceive something that lies beyond our prevailing understanding of knowledge. In other words, dance exposes the limitations of knowledge, or conversely “the boundlessness of our ignorance.”27 By reaching beyond theater to the non-discursive artform of dance, therefore, Depero’s Balli plastici can be said to gain political power. In making use of the intentioned kinetics of dance by bodiless automata, he reveals what we seek in art: the limits of knowledge. While his work cannot be properly called Futurist dance, we can still recognize its moving gestures.

Bibliography

Andrew, Nell. “Dance’s Futurist Moment: Valentine de Saint-Point’s’ Métachorie.” In Nell Andrew, “Bodies of the Avant-Garde: Modern Dance and the Plastic Arts, 1890–1930,” 81–146. PhD dissertation, The University of Chicago, 2007.

Andrew, Nell. “Dada dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction,” Art Journal 73, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 12–29.

Andrew, Nell and Juliet Bellow. “Inventing Abstraction? Modernist Dance in Europe.” In The Modernist World, edited by Allana Lindgren and Stephen Ross, 329–338. London: Routledge, 2015.

Aurier, G.-Albert. “Symbolism in Painting: Paul Gauguin” (1890).” In Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology, edited by Henri Dorra, 195–203. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Bellow, Juliet. Modernism on Stage: The Ballets Russes and the Parisian Avant-garde. Burlington: Ashgate, 2013.

Berghaus, Günter. Italian Futurist Theatre, 1909–1944. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Berghaus, Günter. Theatre, Performance, and the Historical Avant-garde. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009.

Clavel, Gilbert. “Depero’s Plastic Theater.” In Art and the Stage in the 20th Century, edited by Henning Rischbieter. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1968.

Brandstetter, Gabrielle. “Dance as Culture of Knowledge: Body Memory and the Challenge of Theoretical Knowledge.” In Knowledge in Motion: Perspectives of Artistic and Scientific Research in Dance, edited by Sabine Gehm, Pirkko Husemann, and Katharina von Wilcke, 37–46. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2007.

Garafola, Lynn. Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. New York: Da Capo Press, 1989.

Goldberg, RoseLee. Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2011.

Kirby, Michael. Futurist Performance, New York: PAJ Books, 1986.

Lucchino, Gianfranco. “Futurist Stage Design.” In International Futurism in Arts and Literature, edited by Günter Berghaus, 453–456. New York: de Gruyter, 2000.

Lugaresi, Giovanni, ed. Lettere ruggenti a F. Balilla Pratella. Milan: Quaderni dell’Osservatore, 1969.

Ovadija, Mladen. Dramaturgy of Sound in the Avant-garde and Postdramatic Theatre. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2013.

Rainey, Lawrence, Christine Poggi, and Laura Whitman, eds. Futurism: An Anthology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Silver, Kenneth E. Esprit De Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-garde and the First World War, 1914–1925. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Veroli, Patrizia. “The Futurist Aesthetic and Dance.” In International Futurism in Arts and Literature, edited by Günter Berghaus, 422–448. New York: de Gruyter, 2000.

How to cite

Nell Andrew, “Fortunato Depero and Avant-Gard Dance,” in Fortunato Depero, monographic issue of Italian Modern Art, 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/fortunato-depero-and-avant-garde-dance/, accessed [insert date].

- Patrizia Veroli, “The Futurist Aesthetic and Dance,” in International Futurism in Arts and Literature, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: de Gruyter, 2000), 422–448.

- See, among others, Günter Berghaus, Italian Futurist Theatre, 1909–1944 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998) and Günter Berghaus, Theatre, Performance, and the Historical Avant-garde (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009); or RoseLee Goldberg, Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2011).

- A more thorough overview of Avant-garde dance and modernism can be found in Juliet Bellow and Nell Andrew, “Inventing Abstraction? Modernist Dance in Europe,” in The Modernist World, eds. Allana Lindgren and Stephen Ross (London: Routledge, 2015), 329–338.

- Saint-Point would use the terms “ideiste” and “cérebriste” to describe her project, borrowing more Symbolist than Futurist terms. Ideist, for example, was used in 1891 by G.-Albert Aurier to define the emergent style of painter Paul Gauguin. Aiming to express the Idea, Aurier explained Ideist art must therefore be both Symbolist and Synthetist to communicate the idea through forms. See G.-Albert Aurier, “Symbolism in Painting: Paul Gauguin,” in Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology, ed. Henri Dorra (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 195–203.

- For more on Saint-Pointe see “Dance’s Futurist Moment: Valentine de Saint-Point’s’ Métachorie,” in Nell Andrew, “Bodies of the Avant-Garde: Modern Dance and the Plastic Arts, 1890–1930” (PhD dissertation, The University of Chicago, 2007), 81–146.

- There is a spate of letters between Marinetti and Pratella in February 1913 on the subject of a collaboration with Saint-Point, and a plan for Pratella to write the music for a poem in the third section of Métachorie, “Poems of War.” However, when the dance premiered in Paris, Pratella was not on the program. For the correspondence, see Giovanni Lugaresi, ed., Lettere ruggenti a F. Balilla Pratella (Milan: Quaderni dell’Osservatore, 1969), 41. The Métachorie program is reprinted and transcribed in the appendices of Andrew, “Bodies of the Avant-Garde,” 230–236.

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Manifesto of Futurist Dance, July 8, 1917; reprinted in English in Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Whitman, eds., Futurism: An Anthology (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 234–239.

- Lynn Garafola recounts Diaghilev and Stravinsky’s early meetings with Futurists in Rome in February 1915, in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (New York: Da Capo Press, 1989), 77–78. Gianfranco Lucchino dates an even earlier planning meeting between Diaghilev, Marinetti, Boccioni and Balla in Rome, to autumn 1914. Gianfranco Lucchino, “Futurist Stage Design,” in International Futurism, 453–456.

- Mladen Ovadija indicates that Stravinsky was not present during the initial invitation to collaborate, but was in Switzerland. See Mladen Ovadija, Dramaturgy of Sound in the Avant-garde and Postdramatic Theatre (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 2013), 175–176.

- Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero, “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe,” March 11, 1915, reprinted in English in Rainey, Poggi, and Whitman, Futurism: An Anthology, 209–212.

- Rainey, Poggi, and Whitman, Futurism: An Anthology, 212.

- Veroli describes Diaghilev’s visit to Depero’s studio and his suggestions for the artist in Veroli, “The Futurist Aesthetic and Dance,” 431.

- I am indebted to historical and interpretive material from each of these authors. Berghaus, Veroli, and Garafola are cited above. Bellow’s study can be found in Modernism on Stage: The Ballets Russes and the Parisian Avant-garde (Burlington: Ashgate, 2013), 174–175.

- Bellow, Modernism on Stage, 174.

- S.O., “The Russians at Drury Lane,” The English Review 17 (July 1914): 562; quoted in Bellow, Modernism on Stage, 174.

- Fortunato Depero, “Il teatro plastico Depero: Principi ed applicazioni,” Il Mondo 5, no. 17 (April 1919); quoted in Berghaus, Italian Futurist Theatre, 304.

- Veroli suggests that Depero was even involved in the construction of Picasso’s manager costumes for Parade. Veroli, “The Futurist Aesthetic and Dance,” 432.

- The mix of mechanical and real bodies in Parade is made even more complex by Juliet Bellow’s reading in Modernism on Stage. Bellow argues that the disjunction of real and cubist bodies enacting the tension underlying cinematic bodies, as if hovering between photorealism and the planar screen. Bellow begins her study with Cocteau’s statement about the effect of Picasso’s manager figures, who “assume a false reality on the stage to the point of reducing the real dancers to the stature of puppets.” Jean Cocteau, letter to Paul Dermée, in Nord/Sud 4–5 (June–July 1917): 30, quoted in Bellow, Modernism on Stage, 89.

- The political climate surrounding the making and reception of Parade is meticulously presented in Kenneth E. Silver, Esprit De Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War, 1914–1925 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 74–145.

- For Bellow’sa thorough account of Matisse’s work on La Chant du Rossignol, see Bellow, Modernism on Stage, 180.

- “How can we know the dancer from the dance?” reads the final line of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children,” published in London Mercorury 16 (August 1927): 346–348.

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “La danza Futurista,” L’Italia Futurista 2, no. 21 (July 1917). English translation reprinted as Manifesto of Futurist Dance, in Rainey, Poggi, and Whitman, Futurism: An Anthology, 234–239.

- In her careful analysis of the manifesto, Veroli too reads Marinetti’s envisioned performance as imitative, “the dancer’s role is impoverished and dance transformed into a music-hall act” (Veroli, “The Futurist Aesthetic and Dance,” 436).

- I have written more thoroughly on Taeuber’s masked dance in Nell Andrew, “Dada dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction,” Art Journal 73, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 12–29.

- Gilber Clavel, “Depero’s Plastic Theater,” in Art and the Stage in the 20th Century, ed. Henning Rischbieter (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1968), 75; quoted in Michael Kirby, Futurist Performance (New York: PAJ Books, 1986), 113.

- Again, see Bellow and Andrew, “Inventing Abstraction? Modernist dance in Europe,” for a more complete account of these choreographers and their place in European Avant-garde dance history.

- Gabrielle Brandstetter discusses zones of cognitive ‘non-knowledge’ and ‘not-knowing-oneself’ that are touched on by the absence of language in dance. See “Dance as Culture of Knowledge: Body Memory and the Challenge of Theoretical Knowledge,” in Knowledge in Motion: Perspectives of Artistic and Scientific Research in Dance, eds. Sabine Gehm, Pirkko Husemann, and Katharina von Wilcke (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2007), 46.